The following was given as an address at the University of California, Berkeley, on March 22, 1990, where Dr. Bonner was introduced by Czeslaw Milosz.

INTRODUCTION

In this cruel century our common experience has been the individual’s helplessness when confronted by society, by the state, by financial powers, or by police regulations. In spite of the lip service paid to individualism in the West, the individual seems everywhere to be shrinking; and only by being fully aware of our predicament are we able to rejoice when we discover that miracles are possible, and that the determination of one man struggling against virtually insuperable odds can change the thinking of millions of his contemporaries.

Andrei Sakharov had against him all the institutions of his country, including the Academy of Sciences, of which he was a member. He had against him the most powerful police apparatus in the world, and—let us not ignore the truth—he had against him what his resigned compatriots called realism or common sense. His allies were only a handful of so-called dissidents, mostly kept in forced labor camps or psychiatric clinics. We should visualize the years of his exile in a provincial town under police surveillance. He accepted his fate, for he had faith in the final victory of basic human values—but I do not know whether his refusal to compromise would have been possible without the love of Elena Bonner, who gave him her full support in danger. I feel we greet here in her person not only his faithful companion, but the most authentic voice of his deepest convictions.

I am glad I have the opportunity of addressing you as a professor of the University of California, but also as a writer of the Polish language, born in Lithuania. What is going on in the Soviet Union and in the countries of Central Europe concerns me directly, and I realize what the meaning of Andrei Sakharov’s message is at this moment. He was for the friendly and humane coexistence of nations. and publicly condemned the policy of conquest. And certainly he belonged to those Russians who do not visualize the Soviet Union as an empire ruling over nations that would be kept under its control against their will.

The whole part of Europe from which I come is indebted to Andrei Sakharov, for its newly reinvented freedom is to a large degree the result of his courage. At the same time, however, we should be aware of a danger already looming on the horizon, and that danger—noticeable in Russia but also in other countries—is the rise of chauvinism and racism, often concealed in terms of conservative, autocratic, if not outright neo-totalitarian philosophy. And in this respect the heritage of Andrei Sakharov’s thought should be our guide, whether we are Poles, Lithuanians, Hungarians. Czechs, Germans, or Russians, or Americans. The future of my Europe will depend on our ability to overcome national animosities, and to keep alive the spirit of brotherhood, so that the odious past doesn’t poison us again.

All those who pursue this goal will have Andrei Sakharov as their leader.

—C.M.

The full text of Dr. Bonner’s speech follows.

I think that today it is particularly important to speak about the situation in our country, and in the countries of the so-called (and thank God now former) Communist bloc, because the future of all of us depends upon how events in that part of the world unfold; because it is more important now than ever before for people in the West—and particularly Western social and political leaders—to have a concrete understanding of what exactly has changed and what should now be done. What I am about to say I do not consider to be the authoritative “last word” on the subject, but I will say what I think and how I view events.

Five years ago there began in our country a process which is usually called by the now world-famous term perestroika. This word is usually associated with the name of Mikhail Gorbachev, but I would like to remind you that in his 1972 work Memorandum to Soviet Leaders1 Sakharov used all the words that have now become part of fashionable usage: “perestroika,” “glasnost,” “stagnation.” In that work, along with an assessment of the situation in the Soviet Union, he sketched out a clear, systematic plan—indicating what needed to be changed for our country to stop being a monster, terrifying the rest of the world, and for it to join the ranks of other democratic countries.

It seems to me that, having set perestroika in motion, Gorbachev passed through two phases: the first part of this five-year period (two to three years) really did constitute a progressive move forward. During this time “glasnost” really did appear—not full “freedom of the press,” but at least it now became permissible to talk about what had happened in the past—the tragic past of the country—and about those negative elements which persisted from the “stagnation” period. “Glasnost” gave the Soviet reader things that had only been published in the West, and in all of this it performed a great service.

Advertisement

A second point. The early “perestroika years” were notable for the release of a large number of prisoners of conscience. That does not mean that there are no more prisoners of conscience left in our country—there still are, and the struggle on that front must not stop. There is even one new prisoner, whose arrest (for a whole year—a year and two months even—he has been held in jail) is due to nothing other than the fact that he is an Armenian leader of Nagorni Karabakh.2 His name is Arkali Manucharov—he’s an elderly man, he fought in World War II, and I would like to draw your attention to his fate.

The third change that perestroika brought is a change in the policies for leaving the country, both for emigration and in the documentation process for visits to and from the Soviet Union, which has become much simpler. This is a very important, concrete step, because it has eased the plight of many separated families, friends, and loved ones. And—this is a key point to note—all these three steps are achievements toward which people were struggling in the West as well, not just dissidents within the Soviet Union. Sakharov always used to insist on the need for freedom of information, on freedom for prisoners of conscience and the freedom to travel and emigrate.

The fourth important step taken in the perestroika period by Mikhail Gorbachev and his government was the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. The war there brought incalculable misery to the people of Afghanistan, and who knows what its psychological consequences will be for the younger generation in our own country. Our government recently took one more step that was very difficult for it to make. It declared the war to have been an unjust war, a war that should never have even been begun, much less waged—that is, the government admitted its own guilt for the war. I should point out that Sakharov played an important role in this decision. You have probably all seen the television clips [from the first Congress of Peoples’ Deputies in June 1989] in which a young Afghan vet, who lived through the war in Afghanistan and lost both his legs, started to attack Sakharov (the young man was told to do so—he had been specially prepared). Those clips were broadcast all over the country and all around the world. Finally though, under great pressure from Sakharov and the huge mass of public opinion which gathered behind him, our government reluctantly took this decision, a decision which amounted to self-condemnation.

So now I have enumerated the four most important achievements of the first period of Gorbachev’s rule. At the same time as this was going on, several steps were taken on the economic front—steps which turned out to be errors, and which seriously destabilized the financial and economic system of a state that has always had serious difficulties in coping with its economy.

And that is probably all one can say on the subject of “positive steps,” at least with respect to internal policy, because there were also some important changes in foreign policy. Particularly important is the real change in the policy on disarmament.

In Rekjavik, at his meeting with Reagan, Gorbachev refused categorically to examine the problem of rockets in Europe, saying that their removal couldn’t be discussed without parallel examination of the Star Wars issue. Sakharov, immediately after his return from Gorky, made a speech at the Moscow Forum, in which he proposed that it was time to “unite the package” so to speak, i.e., to stop linking these two issues and examine them separately. Two months later Gorbachev made that decision—a decision made easier by the fact that as far back as 1983 Sakharov had been emphasizing that the Western alliance should be allowed to station its rockets in Europe and proceed with the MX missile program, so that it would have a bargaining chip.

These were the first steps that really set an authentic disarmament process in motion, and brought Gorbachev great adulation in the West. And I would fully share the feelings of the West, were it not for other actions of Gorbachev which overshadowed his positive moves, In the country’s internal political life Gorbachev has unfortunately accomplished very little, practically nothing at all. As for the word perestroika (which means “reconstruction”)—when people are renovating their apartment or building a new house, they usually know what it is they’re about to “construct.” Whereas we still do not know. That is, we have not yet had political change and we still have no conception of what will be “constructed” to replace the state which used to call itself “the State of Developed Socialism.”

Advertisement

All the constitutional changes effected by Gorbachev over the last two years concerned only the potential for increasing the personal power of, first, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet and, now, the president. Whereas in actual fact our country needs a new constitutional mechanism that does not proclaim the missionary purpose of communism or of any ideology. Up to now we have been living by a constitution drawn up by Stalin and altered slightly by Brezhnev (for the Party’s benefit). In connection with this Brezhnev constitution, when Sakharov first read a draft of that document in Pravda, he came into the kitchen with the newspaper in his hand—I was cooking at the time—and he said, “I don’t understand what it is we’re being offered—a constitution? Or a new set of Party regulations?”

And with this same constitution, somewhat “corrected” by Gorbachev—but only in the direction of strengthening his own personal power—our state has continued to exist to the present day. Only political, constitutional, change, and only a new treaty between the republics, could help tell us, the inhabitants of the Soviet Union as well as the rest of the world, what will be “constructed.” Our country needs a constitution which defends its citizens and their rights, which defends its constituent peoples. What we need is something like a “Bill of Rights,” but for the moment all we have is a “Bill of the Rights of the State over Citizens, Peoples, Republics.” We need a new constitutional mechanism to regulate national issues, in which no one people would have less weight than any other.

At present we have “peoples with republic status” (fifteen republics), “peoples with autonomous republic status” (slightly lower in status—about the same number as there are republics), “peoples with autonomous region status” (even lower), etc. A total of more than fifty units. The same number as there are states in the US. Each of these units needs to have equal rights. We should have a new “Treaty of Union” between these peoples and the united single state which stands above them. This Treaty of Union cannot and must not be uniform for all republics—each republic, each people should have the right to surrender to higher state management those functions which it may deem necessary. Only the path of a new constitutional agreement between republics can keep our peoples from mutual slaughter.

But Gorbachev has not made a single step along this path. During the five years of perestroika, apart from the first flawed economic reforms, not a single real attempt was made to change the people’s continually worsening material conditions. And I am not exaggerating—the whole country was thunderstruck and dismayed when for the umpteenth time we were offered a Five Year Plan of development, with the promise of future well-being—a plan which was in no way conceptually different from the preceding thirteen Five Year Plans which brought us into poverty. Parallel with this plan, the shelves in stores have emptied, the ruble is undergoing spiraling inflation, and the country is literally becoming impoverished and hungry. Ethnic conflicts are tearing the country apart—blood has been shed—and the overall number of victims in our country is no lower than the number in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

Confrontations between ethnic groups began—at least they came out into the open—with the Armenian-Azerbaijani clashes, but these should not be interpreted as expressions of a true ethnic conflict. Rather it is a conflict imposed by our constitution. This conflict should have been resolved politically when the Karabakh local council decided 121 votes to 3 to annex itself to Armenia. The fact that no political solution could be found on this issue was a grave disappointment for people in all those regions where ethnic contradictions exist. People concluded that the government could not or would not deal with such problems by parliamentary methods; moreover, that it did not even want to negotiate.

The entire Soviet Union saw the session of the USSR Supreme Soviet, in which Gorbachev was literally shouting and shaking his fist at representatives of the Armenian communities. And the result has been an explosion of violence in various places, violence which should really be attributed to provocation by a government unwilling to solve these problems by any means other than the army. And then when the army uses shovels and gas in Tbilisi to disperse the demonstrations, and sixteen girls and several other people are killed, no one is held responsible. With that kind of policy the government cannot expect any response except violence.

It was said out loud at the first Congress of Soviets that forty-three million people in our country live below the poverty line. That’s below the Soviet poverty line of seventy rubles a month. But that figure is a total fabrication—people cannot live on that. Many deputies said that we had to do something immediately to improve the material situation of these people. And the whole country, following the Congress on television, thought that the corresponding decision would be taken. A few months later our rather idle press dug out and printed a story about how Party functionaries were given pay raises right across the board. And when deputies at the Supreme Soviet tried to tackle Gorbachev on this point he said that Party people had a very hard job to do and that few people were willing to do it.

So that is my brief account of the internal situation in my country. When people in the West praise Gorbachev’s actions—and I did say that in international policy there truly have been some real changes—the argument used usually runs like this: “Gorbachev did not use his tanks to invade Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia whereas Brezhnev did.” It’s true—he did not invade, but it is no merit of Gorbachev’s that he did not. Rather it’s his problem, because he cannot. Our army cannot do it, nor can our country as a whole. The army is in a state of psychological stress after the inglorious Afghan campaign.A large number of middle-ranking army officers—indeed the army in general—are finding it very hard to deal with the people’s new attitude toward them after the tragedy in Tbilisi, and the whole country is on the verge of breakup.

And that’s why it was possible, thank God, for what happened in Eastern Europe to happen. On that path we have been outstripped by our Eastern neighbors. In Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, real political changes have occurred. I think that it is the West’s task to create something like a Marshall Plan to help them cope with their economic problems. As for our country, I’m very doubtful whether aid today would be of any use. Without political change that aid will just vanish—as they say in Russia “it will disappear like water on sand.” Or—even worse—it will be used to fortify the still vigorous bureaucratic apparatus of the Party. And that will not only slow down the process of democratic development within the country, but it will be a threat to the West as well.

I think I have shed some light on,…that is, I have explained our view of Gorbachev. The West has a different view. You do not see everything when you are outside—but it is also possible that we do not see everything from inside either. Well, there it is. Both points of view are, I think, worthy of discussion in order to arrive at some kind of concrete decision on the part of the West.

There are still two other particular issues that I consider very important and would like to mention. First of all, Lithuania today. It is quite possible that if the new union agreement which I was speaking about had been concluded a year or two ago then Lithuania would not have seceded. But now we have to deal with a fait accompli. I think that Lithuania was right to select its own path of development. For forty-five years your government’s position was that Lithuania, along with the other Baltic republics, was under occupation by the Soviet Union. For forty-five years your country has been commemorating the national holidays of the Baltic republics. And that is why I simply cannot comprehend why today the US administration, instead of officially recognizing Lithuania as an independent state, is restricting itself to meaningless announcements. It is of no importance whether or not Gorbachev gives assurances that he will or will not use force. But by international law, if you have been recognizing Lithuania as “occupied” then you should now recognize it as “independent.” And I cannot understand the position of the United Nations on this question—total silence.

The second issue—Armenia. Beside the tragic conflict with Azerbaijan, Armenia suffered a terrifying earthquake. Armenia, whose “international aid” (the funds earmarked for quake relief) disappeared—nobody knows where. A people in the throes of severe depression after the earthquake and the totally unjust and unjustifiable decision on Nagorno-Karabakh—that nation is in a terrible state. Today in the Armenian republic, out of a population of just over three million inhabitants, one million are homeless. Today the army is forcibly deporting Armenians from Karabakh, arguing that otherwise they cannot guarantee their safety against attacks by Azeris.

The Armenian people survived the ferocious genocide of 1915—an experience equally tragic for that small nation as their experiences in Germany in the 1940s were for the Jews. The Armenian nation is standing on the threshold of another genocide, and the world community is reacting to this much as it would to a minor ethnic conflict. I was struck by the behavior of the UN General Secretary, who happened to be in Moscow during those days when Armenians were being killed in Baku, when the tanks entered the city, and who said absolutely nothing. I call upon you to help reach a just solution of the Nagorno-Karabakh problem. Today 80 percent of the population there is Armenian, but if the army continues to deport them, it may be that they’ll be saying to us in a few years time: “There’s no problem—there are no Armenians.”

Q: How should the West help groups in the Soviet Union in its evolution toward a liberal democracy?

Bonner: I think I did address that question. After all, President Gorbachev is asking you for—and expecting—material and economic aid. What you should say is: “Make political changes first! We don’t know what you’re going to build with our money.” And I don’t mean that in the concrete sense of “what factory” etc., but what sort of society will be built.

Q: What role have women and women’s groups played in the struggle for freedom and equality in the Soviet Union?

Bonner: You know, our country is on such a low socio-economic level that at the moment we cannot afford to divide ourselves into “us women” and “us men.” We share a common struggle for democracy, a struggle to feed the country.

Please tell us about the outburst of anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union and about what if anything is being done by the Soviet government in that regard.

Bonner: I’ll say this—I do not think that we are experiencing an explosion of anti-Semitism. I do not even believe that there is any more anti-Semitism now in our country than there always has been. However, we are experiencing an explosion in the activities of the organization Pamyat [Memory] and of other organizations like it. I am absolutely sure that these Pamyat organizations are intertwined to some degree with the state and Party apparatus, and with their help a new National Socialist ideology could certainly emerge. I think that is a great danger, and I would like our government to take some real steps to fight the phenomenon. Until now, however, we haven’t seen a single actual judicial prosecution for incitement to racial or ethnic conflict, and there have been no statements on the subject from leaders, including Gorbachev. I would like to hear from him personally what he thinks about this.

What was the attitude of Andrei Sakharov toward Gorbachev?

Bonner: He had a twofold attitude toward him. Andrei Dmitrevich spoke about this in public—in the US too. He said that he supported Gorbachev in some areas, but that other areas of Gorbachev’s policy gave him grounds for concern. And…incidentally, in his book, which will be published shortly, he wrote about his attitude to Gorbachev in some detail. An example of that attitude: at the first Congress [of People’s Deputies], when Gorbachev was being elected chair of the presidium without any alternative candidates on the ballot, Andrei Dmitrevich would not take part in the voting and even made a demonstrative exit from the hall. The next day Gorbachev asked him: “Why did you walk out?” To which Andrei Dmitrevich replied: “We have already had seventy years of elections without alternative candidates in this country and I don’t intend to play this game any more.”

—translated by Conor Daly

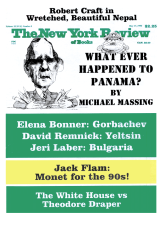

This Issue

May 17, 1990