Few Japanese—if any—have forgotten that dark day in October 1964, when Anton Geesink beat the Japanese judo champion Kaminaga Akio to win the Olympic gold medal in Tokyo. The Dutch giant—six foot six inches, 267 pounds—didn’t just beat Kaminaga, he flattened him. And the nation wept, quite literally. Grown men, pressed against shop windows to see the fight on television sets especially provided for this purpose all over Tokyo, collapsed in tears. Geesink told reporters that coping with the Japanese crowds after the fight had been tougher than the fight itself.

Judo had been introduced that year for the first time in the history of the Olympic Games by special request of the Japanese hosts. Judo was not just a national sport; it symbolized the Japanese way—spiritual, disciplined, infinitely subtle; a way in which crude Western brawn would inevitably lose to superior Oriental spirit. And here, in Tokyo, a big, blond foreigner had humiliated Japan in front of the entire world. It was as though the ancestral Sun Goddess had been raped in public by a gang of alien demons. The disaster was blamed on Geesink’s bulk, of course, but that rather left one wondering about this business of spirit versus brawn.

Sport, like sex, cuts where it hurts most: that soft spot where national virility is at stake. Nowhere is it more sensitive than in Japan, the peripheral nation, always on the outside edge of greater powers, always panting to catch up with the foreign metropolis: Chang-an, Peking, Paris, London, New York. And at no time was it more delicate than in the 1960s, when the nation was beginning to crawl away from the shadow of the greatest humiliation of all: defeat in war and subsequent occupation by a superior foreign power. The Tokyo Olympics were supposed to have put the seal on all that. The revival of national virility, already boosted by the accelerating economic boom, was at hand; the Judo Open Weight gold medal was meant to have clinched it; the shame of defeat would be wiped out and Japanese face would finally be restored.

The writer Nosaka Akiyuki described exactly what it was all about in a wonderful novella, published in 1972, entitled American Seaweed. A Japanese man is visited in Tokyo by an American acquaintance who had served in Japan during the occupation. For his entertainment, the American guest is taken to a live sex show, where Japan’s “Number One Male” is to perform. On this occasion, however, Number One, possibly distracted by the American in the audience, fails. The Japanese host is as embarrassed as the star performer but understands his predicament:

As soon as those jeeps started racing through his mind, cries of ‘come on everybody’ rang in his ears, and sad memories of brilliant skies over burnt-out bomb sites returned, he was rendered impotent…

Strong measures, in such humiliating circumstances, were called for. And in the late 1950s national virility was redeemed somewhat in the spectacular shape of Riki Dozan, a large and very virile wrestler who specialized in beating big, blond Americans—often wearing cowboy hats—to the mat. Riki Dozan was the perfect Japanese macho man: he had fighting spirit to burn. But he always spoke fondly, even tearfully, of his mother, was benevolent to his juniors, and fought fairly. The outsize Americans, on the other hand, fought dirty. But despite the hidden knuckle-dusters and other weaponry suddenly produced by these dastardly foreigners, Riki Dozan’s fighting spirit would invariably prevail. In comic-book versions of his career, this indomitable spirit was inspired by frequent visions of Mount Fuji. Few men in the history of modern Japan have been more popular. That he was actually born a Korean, like so many other Japanese sporting heroes, was something people preferred to ignore. Hence when he was stabbed to death in a Tokyo nightclub a year before the Tokyo Olympics, only one national newspaper cared to mention this unfortunate blot on his otherwise exemplary biography.

Given all this, Anton Geesink’s victory was deeply shocking. Yet to say that he was not respected in Japan would be untrue. Despite the national shame of Kaminaga’s defeat and the common air of contempt for big, blond (not to mention black) foreigners, Geesink’s power was held in awe. He was a bit like the demon guardians of hell that stand by the gates to Japanese temples, to be approached with a proper sense of trepidation. But as soon as the great Judoka’s powers began to flag, and he was foolish enough to appear in degrading wrestling exhibitions, awe and trepidation swiftly changed to ridicule. Once Samson is shorn of his locks, the Japanese show little mercy. Geesink’s position in Japan was typical of the way in which foreign demons have traditionally been treated by the Japanese: worshiped one day, despised the next, all according to the state of their virility.

Advertisement

Too much foreign virility, however, is not a good thing either. It upsets the natural, that is to say, the Japanese order of things; it upsets harmony, or wa. The fascinating story of Warren Cromartie, the black American baseball player, formerly of the Montreal Expos, is typical of that ups and downs to which the foreign demon is subjected in Japan. In 1983 he was offered a three-year contract by the Tokyo Giants to play for $600,000 a year, roughly ten times what most Japanese players made. He was met at Narita Airport by the general manager of the Giants, who stuck out his hand, bowed, and said: “Welcome to Japan, Mr. Cromartie, you are our messiah.”

Five years later, with a .313 batting average and 160 home runs to his name, his picture was missing from the Giants’ Gallery of Stars outside the team’s home park. Nor was he asked to endorse products, like his Japanese colleagues. Nor was his name mentioned by the club’s dignitaries in their celebration speeches, after he had helped win the championship pennant. Instead, the Japanese players were exhorted to play better than the imported “gaijin,” or foreigner. And when the team went through hard times, the gaijin would be blamed for his lack of spirit, his greedy materialism, and his selfish ways, which upset the wa of the team. In Cromartie’s own words, quoted by Robert Whiting, who helped write the autobiography and has written two excellent books on Japanese baseball himself: “You’re an outcast no matter what you do. You go 5-for-5 and you’re ignored. You go 0-for-5 and it’s ‘Fuck you. Yankee go home.”‘1

The case of Randy Bass, described in Whiting’s book You Gotta Have Wa, is even more remarkable. Bass, a lefthanded power hitter from Oklahoma, started playing for the Hanshin Tigers in 1983. He, too, was greeted as the Messiah. He even got to do endorsements on Japanese television—as more than one Japanese politician has hinted in the past, the Japanese tend to prefer blonds to blacks. So Bass was doing all right. Then he threatened to break the home-run record, established in 1964 by Oh Sadaharu, who hit fifty-five homers in one season. When Bass got to number fifty-four, with two games left, the Japanese closed ranks. He hardly had a chance to hit another ball and was forced to walk in almost every inning. The record remained in local hands. Wa was preserved. If this was upsetting enough to Bass, worse was to follow.

After going from strength to strength and winning virtually every trophy there was to win, after becoming the most popular gaijin player in Japan, after being offered bigger and bigger contracts, after beating Harimoto Isao’s single season average of .383 (eliciting Harimoto’s remark that Asian baseball should be for Asians only—Harimoto, like Riki Dozan, was a Korean), after hitting thirty-seven homers in 1987, with a bad back, after all that, Bass’s eight-year-old son was discovered to have a brain tumor, and Bass flew to San Francisco to be by his side. While he was still in the US, the Tigers decided to drop him. Bass was accused of selfishness, of lacking team spirit, of putting his private affairs before those of his club, of not understanding wa. “Foreign players are just not a good example for young people,” wrote Harimoto, the man who was often taunted by Japanese young people with cries of “garlic belly,” because of his Korean birth.

Cromartie’s book could so easily have been a litany of gaijin complaints, the sort of thing that can make expatriate conversations so deadly. It is actually much better than that, for he is not bitter about the country that provided him with so much anguish as well as cash. His own background gave him an interesting perspective on the gaijin experience: “I’ve always been a gaijin, you might say. I grew up in Liberty City, the poor black section of Miami, where most people were lifetime outsiders….” And, in fact, the life of the gaijin ballplayer had some notable perks, not the least of which were the many opportunities to get laid. Cromartie is discreet on this score, though there are coy references to what “the guys tell me,” but he does reveal that he had some “real relationships, not one-night stands.” Which means that he actually bothered to get to know people, which is more than many expatriates do. It shows in his observations, which are both sharp and affectionate.

He is careful to distinguish between the many Japanese individuals, players as well as non-players, who were friendly and supportive, and the officials and their lackeys in the popular press, who made life a misery for foreigners as well as Japanese. Some of the most moving passages in the book concern Cromartie’s friendship with the Giants’ former manager and batting star, Oh Sadaharu, the half-Taiwanese who was forever trying to prove to his Japanese compatriots that he had the true samurai spirit in spite of his Chinese blood.

Advertisement

Cromartie’s most important insight is one that many complaining gaijin tend to overlook, and one which can be applied far more widely than to the sporting world alone: the main victims of the bigoted, exclusive, rigid, racist, authoritarian ways of Japanese officialdom are not the foreigners, even though they are at times its most convenient targets, but the rank and file of the Japanese themselves. The pampered foreigner, brought in to lend power to the Japanese baseball scene, but exempted from many of the rigors of Japanese discipline, is not just a convenient scapegoat to save Japanese face when things go wrong, but also a kind of anti-Christ to keep the Japanese in line. If Japanese players should balk at being kicked around, underpaid, and overdisciplined, their frustration can be neatly channeled toward the overpaid, underdisciplined, greedy, selfish foreigner. “The Japanese,” writes Cromartie,

always complained that we gaijin were overpaid. The commissioner of Japanese baseball in fact was always urging a complete ban on foreigners, saying it was degrading to Japanese baseball to have to pay big money to Americans who were washed up in the U.S.

The reality, however, was that the Japanese were getting screwed.

When the Japanese players finally formed a union to get a better deal out of their very rich clubs, the union’s elected chief told Cromartie that “they’d never strike because it wouldn’t be fair to the fans.” A Japanese writer then explained to Cromartie that professional baseball players were supposed to be “clean, simple, and obedient.”

Now, one might say that this simply shows a difference in culture, that the American is not necessarily better off, that loyalty, team spirit, and a sense of belonging are more important to a Japanese than his personal interests, but one should bear in mind when saying so that this is exactly how men in positions of power, corporate, bureaucratic, or political, justify the manner in which they continue to keep other men and women down.

Cromartie is highly instructive on how obedience is instilled in Japanese baseball teams. It begins with what a much revered Meiji-period gentleman named Tobita Suishu, also known as the “god of Japanese baseball,” liked to call “death training.” This meant drilling players until, in Tobita’s words, “they were half dead, motionless, and froth was coming out of their mouths.” (He was referring at the time to the training of high-school boys.) One such drill, still practiced by all serious coaches in Japan, is the “thousandfungo drill.” In Cromartie’s words: “The coaches would take a guy out and hit ground balls to him until he collapsed…. The guy would be flat on his back, and the coaches would praise his fighting spirit.” A variation was the “Ole infielder’s Drill,” described by Robert Whiting:

In this drill, a coach will stand the player on the third base line about twenty feet away and begin to hit bullet-hard line shots at him. Thirty minutes later the player’s body is black and blue, one or two fingers are bent back, and more often than not, he is on the verge of tears.2

When one of Cromartie’s teammates, a player named Makihara, developed a sore arm by pitching too many balls, he was sorted out in the following manner:

Every day the coaches would hit grounders to Makihara until he couldn’t stand up, yelling insults at him all the while…. Then they’d make him run four or five miles. Once, when a coach thought Makihara wasn’t trying hard enough, he grabbed him by the neck and hit him over the head with the end of a bat.

The idea of all this is to nurture spirit, or “gutsu.” Old-fashioned Japanese call it seishinshugi, or spiritism. They like to think of it as uniquely Japanese, a tradition handed down from ancient times. In fact, like the Darwinist notion, still widely accepted in Japan, that man’s destiny is determined by a worldwide racial virility struggle, it has its European counterparts. Spiritism is the old belief that a show of will can overcome any obstacle, that spirit is superior to strength, and collective discipline superior to individual talent. The fact that Japanese players are often too exhausted by incessant drilling to do well in the actual games doesn’t mean that they are given a rest. On the contrary, to build up their flagging spirits, the coaches order more drills.

This military or samurai approach to playing sports or, indeed, making cars, can have remarkable results. There was once a schoolboy pitcher called Bessho Takehiko, who won the baseball championship for his school in 1941 by pitching with a broken arm. He was soon to be sent to the war. “I want to play as much baseball as I can before I die,” he said. But Cromartie is not the only one to detect deep flaws in this approach. Not only are the players often too tired to give their best, but their morale is sometimes oddly brittle. When human will is driven to a pitch of group hysteria, it tends to snap quite suddenly when faced with adversity. Cromartie often saw his team go from overconfidence to listlessness when things weren’t going their way. This is also what people observed in a very different contest, when Japan was collapsing in 1945. Far from being a nation of iron-willed people, bent on fighting to the end, the Japanese were going through the motions of the drills they had learned, without enthusiasm, certainly without fanaticism.

Extreme group discipline, though highly effective on an assembly line, does not always work so well in a crisis, for crises demand individual initiative and imagination, the very things spirit training aims to eliminate. The problem with Japanese baseball, as Cromartie saw it, was that the Japanese players always had to be told what to do: “Take an extra base without a coach’s express order, and there’d be hell to pay.” Doing one’s duty and staying out of trouble—“clean, simple, and obedient”—was more important than winning the games. When things went wrong, the individualist gaijin could be singled out for blame. And when the more conscientious foreign players, some of whom were actually hired as coaches, tried to improve the Japanese game in the only way they knew how, by encouraging players to think for themselves, they were seen by Japanese managers as a threat and eventually rejected. No wonder many gaijin players were confused: hired to do well, they were sometimes actively prevented from doing so. And no matter how hard they tried, they would still be told they were only in it for the money.

That Warren Cromartie managed in the end, through sheer perseverance, to be accepted by most of his teammates as one of the guys, was a great tribute to him. All the more so, since the Tokyo Giants are more than just another baseball team, they are a Japanese institution, which used to pride itself on the purity of its players’ bloodlines. As one typical fan remarked to Robert Whiting in a Tokyo bar: “I’m Japanese, so I like the Giants.” But Cromartie’s very success might have made the club’s officials nervous. He might give his Japanese colleagues the wrong ideas. They might start to behave like him. Think what that would to do to wa?

In fact, there have been Japanese rebels in the baseball world. The most prominent one was a third baseman named Ochiai Hiromitsu. He was so individualistic, so downright cussed in his ways, that the Japanese call him The Gaijin Who Spoke Japanese. Cromartie liked the sound of this man and tried to hug him once during a match. Ochiai grunted and pushed him away. Whiting has a good quote from Ochiai on spirit and wa:

The history of Japanese baseball is the history of pitchers throwing until their arms fall off for the team. It’s crazy. Like dying for your country—doing a banzai…with your last breath. That mentality is why Japan lost the war…. Spirit, effort, those are words I absolutely can not stand.3

Just imagine if more Japanese began to talk like that, instead of venting their frustrations as Cromartie’s teammates did by smoking too many cigarettes and reading sadistic sex comics.

This has been the worry of Japanese officialdom (and Chinese, too) for centuries, and it is at the heart of their dilemma: How to build up national strength by learning from the West, without damaging the spirit of wa? Eighteenth-century thinkers were particularly worried that Christianity would, in the words of one Japanese scholar, “incite stupid commoners to rebel.” How to separate Western techniques from Western ideas that might upset the Eastern order? A formula was imported from China called Wakon Yosai, literally Japanese Spirit, Western Skill. The scholar quoted above, called Aizawa Seishisai, also wrote the following words, which express the sentiments of some modern Japanese exactly:

Barbarians are, after all, barbarians. It is only natural that they adhere to a barbarous Way, and normally we could let things go at that. But today they have their hearts set on transforming our Middle Kingdom Civilization to barbarism. They will not rest until they desecrate the gods and destroy the Way of Virtue…. Either we transform them or they will transform us—we are on a collision course.4

If this sounds a bit like the language used by some Westerners who warn us of the imminent Japanese peril, it is no coincidence. For it is the language of moralists who seek transcendental means to order human society. It is, if you like, the religious approach to politics, the idea that international relationships are a contest of absolute values. What moralistic western critics of Japan have in common with many Japanese conservatives is the worry that the Japanese state lacks a clear moral goal. The kind of people in Japan who believe that foreign traders, foreign intellectuals, and indeed foreign baseball players, however desirable the skills they bring, are a threat to the Japanese Way, also have a religious belief in the hierarchical Japanese order, symbolized by the chrysanthemum throne, which cannot be open to challenge—not by foreigners and certainly not by the “stupid commoners” of Japan.

In the world encountered by Cromartie, Bass, and many other gaijin players, this order seems to have been astonishingly well preserved. To be sure, the world of baseball, or any sports, is more conservative than other parts of Japanese life. Yet there is little sign of change in the Japanese order. In the name of wa, Japan remains a rather closed society, where most people continue to be bossed around by unaccountable men in power, whether they be gangsters, bureaucrats, or baseball coaches. The problem for the non-Japanese world is not that the Japanese, through extreme diligence and discipline (Madame Cresson’s “ants”), will beat us at trade and, who knows, eventually at baseball, but that the defense of wa remains inextricably linked to the virility struggle of nations. A Darwinist idea, discredited in most of the Western world, is still around to haunt us from the East.

But let us return to the common-sense language of baseball. I could not express the problem of Japan and its relations with the world better than Reggie Smith, who was still playing for the Tokyo Giants when Warren Cromartie was greeted as the new Messiah at Narita International Airport:

To say, like Oh and the others are saying, that Japanese baseball should be played by Japanese or Asians alone and that a real World Series between Japan and the U.S. would be impossible as long as there are American players in Japan, seems to me just racist….

The world is getting more international anyway and the Japanese should be thinking “team versus team” or “league versus league.” Instead it seems that Japan is still |vicariously fighting World War II. It’s like the South in the U.S., still trying to hang on to slavery and segregation.5

Reggie Smith had once been a Messiah too. But after one highly successful season, he failed to find his touch. The Japanese press called him a brokendown jalopy. He began to lose his temper and beat up sports fans who shouted “Nigger!” at him. Not long after, the Tokyo Giants decided to let him go.

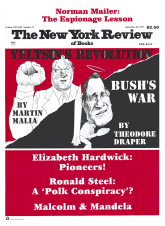

This Issue

September 26, 1991

-

1

This quote is from You Gotta Have Wa (Macmillan, 1989), p. 262. Whiting’s first book on Japanese baseball is The Chrysanthemum and the Bat (Dodd, Mead, 1977). ↩

-

2

Whiting, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, p. 52. ↩

-

3

Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa, pp. 203–204. ↩

-

4

Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, Anti-Foreignism and Western Learning in Early-Modern Japan (Harvard University Press, 1986). ↩

-

5

Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa, p. 312. ↩