1.

“No one who has not pioneered can understand the fascination and the terror of it.” Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote these words. They appear on a historical plaque by the side of South Dakota State Highway 25, a mile and a half north of the town of De Smet. The plaque marks the site where Wilder and her husband, Almanzo, lived in a claim shanty in the late 1880s while they tried and failed to grow wheat.

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s series of autobiographical novels for children—the most famous is Little House on the Prairie—still conveys the fascination and the terror that the Great Plains held for those from the east who attempted to settle them. Published between 1932 and 1943, the eight “Little House” books describe Wilder’s childhood homes in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Indian Territory (now Kansas), and Dakota Territory. They remain the most popular fiction about the opening of the western frontier to home-steading, beloved in a way that realist adult fiction about the same era has never been. The books have also inspired a variety of often sentimental homages: memorial societies, museums at the sites of Wilder’s homes, a bowdlerized television series, and a variety of sequels and imitations.

Beyond their appeal to children, the “Little House” books are serious works, meticulous first-hand accounts of a family’s struggle to survive in a harsh and unfamiliar world. They are also lyrical—even romantic—in their depiction of the effects of terrible losses, of crops, homes, and health, and of deep poverty on the people of the small towns and farms of the prairies. Although poor in possessions, the central character, Laura Ingalls, has a rich sensual and spiritual appreciation of the natural world.

The myths of the opening of the frontier, the settling of the West, and the proliferation of the stock figures of the heroic frontiersman, the Indian fighter, the cowboy, the outlaw, and the rest have been re-examined and debunked in all kinds of ways, from the movies of Sam Peckinpah to recent revisionist academic works.1 From the 1890s on, novelists, journalists, and, not least, those who lived through the period have offered realistic accounts of the arrival of white settlers and the often unhappy consequence for themselves, for the native peoples who already lived in the West, or for the land. Wisconsin Death Trip (1973), Michael Lesy’s horrifying compilation of period newspaper photographs and clippings reporting crimes, suicides, alcoholism, and insanity in a small Wisconsin town during the 1880s and 1890s, graphically documents the blunted lives in isolated American towns during the same period Wilder described. So does the fiction of the period. Ole Rölvaag, a Norwegian who emigrated to South Dakota as a young man in 1896 (two years after the Wilders left it), in Giants in the Earth: A Saga of the Prairie (1927) tells of the wife of an emigrant who was driven to religious madness by her hatred and fear of the empty spaces of the plains.

Although Wilder softened her account in certain ways, eliding references to events that seemed horrific for children, she herself contributed to a realistic picture of frontier life. The fifth book in Wilder’s series, By the Shores of Silver Lake, includes an account of a near riot of disgruntled rail-road workers; in the seventh, Little Town on the Prairie, one scene dramatizes public drunkenness; and in These Happy Golden Years, the last book published in Wilder’s lifetime, a woman driven to domestic despair in a Dakota claim shanty threatens her husband with a knife.

Wilder also found beauty and familial pleasures in conditions others would deplore. As a child, she crossed paths with the young Hamlin Garland at a Christmas pageant in Iowa. He, too, had grown up as a child of home-steaders, but in Main-Travelled Roads, his 1891 collection of short stories, Garland wrote (as Howells described it) with “a certain harshness and bluntness,” reproducing the crude, inarticulate speech of pioneers and cataloguing the coarse realities of their lives. And when Garland wrote about his youth he was implicitly comparing the western landscape with the more “civilized” ones of his adulthood:

No other climate, sky, plain, could produce the same unnamable weird charm. No tree to wave, no grass to rustle, scarcely a sound of domestic life; only the faint melancholy soughing of the wind in the short grass, and the voices of the wild things of the prairie…. The silence of the prairie at night was well-nigh terrible.

Of those same prairies, Wilder wrote,

Everything was silent, listening to the nightingale’s song. The bird sang on and on. The cool wind moved over the prairie and the song was round and clear above the grasses’ whispering. The sky was like a bowl of light overturned on the flat black land.

Writing through the eyes of a child freed Wilder to express the anarchic delight and fear such a landscape could inspire, without resorting to moralizing or the rhetoric of alienation. This nocturnal idyll goes on to describe the nightingale answering her father’s fiddle and the fiddle responding until “the bird and the fiddle were talking to each other in the cool night under the moon.” Like the American poet Wallace Stevens who would write of a bird singing “without human meaning, / Without human feeling,” Wilder loved the inhuman ways of the world.

Advertisement

Yet the “Little House” books have almost always been characterized as simplistically domestic in subject and moral in purpose. An early review in The Horn Book lauded their depiction of “family life,” and The New Yorker praised “their warm-hearted human values.” Douglas MacArthur had the State Department translate the novels into Japanese and German after World War II, as if they were propaganda for the American way of life. In a recent interview, William Holtz, the author of The Ghost in the Little House, the recent biography of Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, said that “traditional family values, traditional patriotic values…are in the books, and nothing I’ve said can take them out.” The most pernicious distortion of Wilder’s material was accomplished by Michael Landon’s 1974–1983 network television series, Little House on the Prairie, which reduced her work to a pioneer version of The Waltons.

From the Bible to Grimm to the present, stories perceived as moral fables are subject to inauthentic retellings and revisions, especially when the intended recipients of such moral truths are children. Ambiguities are dropped. Whatever is gory or graphic or violent—and thus of particular interest to children—is obscured. But as Alison Lurie has demonstrated in her exploration of “subversive” children’s classics, Don’t Tell the Grown-ups, the literature that remains perennially popular with children more often than not contradicts or undercuts the received moral wisdom. Lurie’s book omits any mention of the “Little House” books, but Wilder’s writings support her thesis. They are certainly popular: over 40 million copies have been sold, and the series has been translated into fourteen languages. They have become classics because every child recognizes the anarchic feelings they describe.

In fact, Wilder’s preoccupations—the absolute dependence of children on their parents, the joys and dangers of nature, the intense satisfactions of even the simplest forms of food, shelter, and companionship—are not those of a moralist. While Pa possesses a nearly indestructible cheerfulness, and Ma has a dogged determination to find the silver lining in the clouds that destroy a crop or bring a blizzard, Wilder herself virtually insists on the arbitrariness of life in her accounts of the storms, tornadoes, grasshopper plagues, and illnesses that derange the order of their world.

In a lecture she gave in 1937, Wilder recalled several grisly incidents which she omitted from her novels, including the murder of a neighboring family and the deaths of children she knew in a blizzard:

There were some stories I wanted to tell but would not be responsible for putting in a book for children, even though I knew them as a child….Sister Mary and I knew of these things but someway were shielded from the full terror of them. Although we knew them true they seemed unreal to us for Ma was always there serene and quiet and Pa with his fiddle and his songs.

As an adult, Wilder may have convinced herself that she felt shielded from “the full terror” of the events of her childhood, but that is not how she describes her experience in her novels. In the books, Laura must constantly remind herself that her father and the family watchdog will protect her: “Pa was on the wagon seat and Jack was under the wagon; she knew that nothing could hurt her while Pa and Jack were there,” and “Jack wouldn’t let anything hurt her.” Wilder left out particular stories of terror, but she did not leave out the sense of threat, the potential for violence, the fear of death. In On the Banks of Plum Creek she and her sister fear that their father has been frozen to death in a blizzard. There is room in the “Little House” books, as there may not have been in the real houses on the prairie, for a child’s unsocialized, chaotic desires and fears.

Wilder’s series describes a life of nearly unrelenting hardship and danger. But the vocabulary and style of each of the novels are tailored to the age of their protagonist, Laura Ingalls, and the first volume, Little House in the Big Woods, in which Laura is five, is the sunniest and most carefree in both tone and subject. As it follows the seasons from winter to fall, the story traces Laura’s struggle to “mind,” a struggle in which she is aided by her father’s comic and instructive tales of his own boyhood. Still, the novel opens with an intimation of the dangers that lurk outside even this safest of houses:

Advertisement

Once upon a time, many years ago, a little girl lived in the Big Woods of Wisconsin, in a little gray house made of logs.

The great, dark trees of the Big Woods stood all around the house, and beyond them were other trees and beyond them were more trees. As far as a man could go in a day, or a week, or a whole month, there was nothing but woods. There were no houses. There were no roads. There were no people. There were only trees and the wild animals who had their homes among them.2

Two pages later, Laura hears a wolf howling near the house: “It was a scary sound. Laura knew that wolves would eat little girls.” And if wolves are part of a fearful world outside the family circle, Laura herself fears that she is not as pretty, not as good, not as loved as her older sister, Mary, with her golden curls and perfect manners. Laura’s belief that her character, like her hair, is “ugly and brown” inspires a competitiveness, a determination to prove herself, that becomes a theme throughout the novels.

Although the “Little House” books explore family tensions and are punctuated by terrifying natural disasters, they also evoke, in their orderly description of human activity, a sense of safety. The juxtaposition of intermittent danger with the lulling normalcy of the chores of daily life is the characteristic device of the third novel, the one Wilder called her “Indian story”—Little House on the Prairie. Arbitrary mishaps and mysterious visitations occur: the whole family abruptly falls ill with chills and fever (which they do not know is malaria); fire sweeps the prairie; wolves sit in a circle around the family’s cabin and howl. But in the safety of the novel, Wilder can explore what must have been, in her own life, the terrible and forbidden, her fascination with those beings she most fears: the wolves and the mysterious Indians who seem to appear out of the earth itself and disappear back into it.

The novel documents the family’s search for a good piece of land and the construction of their home. On the journey westward, they are nearly swept away crossing a swollen river in their covered wagon, and almost lose their invaluable watchdog, Jack. After finding a homestead, they build a cabin and stable, dig a well, and prepare fields for crops and a garden. The particularity with which each of the most humble of human undertakings is described—the preparation of the simplest of meals, the buttoning of a dress, the packing and unpacking of the precious few belongings, even the circling of the dog as he makes his bed in the prairie grass—is fascinating in and of itself, a vivid record of a lost way of life. Each task, as it is carried out by Pa or Ma, is lovingly, calmly described—the construction of the cabin walls, the cabin door, its hinges and latch, the stone hearth and chimney. But the attention to detail is also an emotional refuge, and it captures a child’s ability to ease anxiety by losing herself in the contemplation of the orderly and ordinary. A number of frightening accidents intrude on this order: Ma’s ankle is injured when one of the heavy logs falls on her; a neighbor helping Pa to dig the well passes out, overcome by unknown gasses. But their fearsomeness is somehow diminished in intensity, if not in drama, in the retelling.

The narrator repeatedly and flatly notes the absolute necessity for the children’s swift, silent obedience; after the near disaster of the river crossing, for example, she offers this frank conjecture: “If Laura and Mary had been naughty and bothered [their parents], then they would all have been lost.” Being “naughty” in this instance refers to crying in fear; indeed, had Mary and Laura distracted their parents during the split seconds in which they had to lead their swimming horses to safety, they might all have drowned. On the Great Plains during the 1870s, the suppression of feeling was not simply a nineteenth-century social nicety. Life itself could depend upon it. But in these novels, what had to be suppressed in life finds expression.

2.

Laura Elizabeth Ingalls, the pioneer child who would grow up to write about her family and their “little houses,” was born on February 7, 1867, on a farm outside Pepin, Wisconsin, the second child and daughter of Charles and Caroline Ingalls. Laura’s older sister, Mary, was born two years earlier on the same farm (the “Big Woods” of Wilder’s first book), where Charles Ingalls supported his family by hunting, trapping, and growing crops of wheat and oats. The family moved continually. Carrie was born in 1870 in a log cabin in Indian Territory, the home described in Little House on the Prairie. Charles Frederick (never mentioned in the novels) was born in 1875 in Walnut Grove, Minnesota, the home in On the Banks of Plum Creek, and he died a year later. The last of the Ingallses’ children, Grace, was born in 1877 in Burr Oak, lowa, where the family worked in a hotel. The Ingallses returned to Walnut Grove in 1878, and a year later moved on to Dakota Territory and helped found the town of De Smet, now in South Dakota.

These moves apparently reflected Charles Ingalls’s restless desire to go west, as the east was settled, progressively deforested, and depopulated of game. Indeed, it is possible to trace in the novels the speed with which the ecology of the Great Plains was altered by settlers, even as it defeated their farms. Over the course of a few years, the country that is so rich in fish and game in On the Banks of Plum Creek is depleted. In the next novel, By the Shores of Silver Lake, Wilder writes: “Only a few small fish were left in Plum Creek. Even the little cottontail rabbits had been hunted until they were scarce. Pa did not like a country so old and worn out that the hunting was poor.” The more immediate motive for moving on was always disaster and misfortune: bad luck, crop failures, illness, debt. The Ingallses were forced to leave their homestead in Indian Territory after inadvertently building their cabin on disputed tribal land; they had to leave Walnut Grove after a plague of grasshoppers wiped out their wheat crop; they pressed on to De Smet after scarlet fever blinded Mary. And it was in the relative safety of their home in De Smet that they nearly starved to death, along with the rest of the town, during the record blizzards of the winter of 1880–1881.

In 1885, when she was eighteen, Laura Ingalls married Almanzo Wilder. Her married life was early on marked by hardships even more severe than those she had already known. Living on their own homestead claim near De Smet, the young couple quickly ran up debts for farm machinery and doctors’ bills as drought and hail storms destroyed their crops. The Wilders’ first child, Rose, was born on December 5, 1886. In 1887, their barn and haystacks burned down. In 1888, both husband and wife contracted diphtheria; while he was recovering, Almanzo Wilder, then thirty-one years old, was partially paralyzed by a stroke. In 1889, their second child, a boy, died twelve days after he was born. Two weeks after his death, the Wilders’ house burned to the ground.

In 1894, the Wilders left South Dakota for Missouri, bought forty acres near the town of Mansfield, and built a farmhouse with timber from their land. They struggled for some years; Almanzo planted an apple orchard and worked at odd jobs while Laura, who named their acreage Rocky Ridge Farm, became known as a purveyor of exceptional butter and eggs, which brought high prices. In 1911, at the age of forty-four, she began to write about farm life for the Missouri Ruralist, sometimes incorporating memories of her pioneer childhood into her essays.

Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, became a journalist and writer. She encouraged her mother to turn her autobiographical letters and sketches into a book that might augment the family’s income. In the late Twenties, after the deaths of her mother and her sister Mary (her father had died in 1902), Wilder began working on two different manuscripts: “Pioneer Girl,” a short autobiography, and “When Grandma Was a Little Girl,” a children’s story incorporating tales her father had told her. The second manuscript, retitled Little House in the Big Woods, was published by Harper and Brothers in 1932, when Wilder was sixty-five. Despite the Depression, the book sold several thousand copies immediately, at the time a remarkable accomplishment for a children’s novel. It won the first of the five Newbury Honor Awards the books would earn.

Wilder’s next novel, Farmer Boy, based on her husband’s memories of growing up on a prosperous farm in upstate New York, was published in 1933. She returned to her own childhood with Little House on the Prairie in 1935, and its sequels, the fifth and last of which, These Happy Golden Years, was published in 1943. Almanzo Wilder died in 1949 at the age of ninety-two. Wilder spent the last decade of her life answering letters from her readers and speaking occasionally at public libraries. She died at Rocky Ridge Farm on February 10, 1957, three days after her ninetieth birthday.

Many of the classic American novels for children—Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, A Little Princess, The Secret Garden, and even Charlotte’s Web—concern children (or pigs) who are orphans and must make their way in the world without the help of their families. The “Little House” series is one of the few profound explorations of familial relationships in American children’s literature. But with all due respect to Tolstoy, all happy families are not alike and the happy family Laura Ingalls Wilder describes—with all its accommodations, compromises, and repressions—is as tragic in some respects as any unhappy family.

Wilder struggled to recast the literal events of her life into a progressive narrative: a story of moving westward and onward, of maturing, improving, succeeding. This struggle determines the structure of the narrative, its avoidance of bathos, its refusal to dwell on the sorrowful or the terrible; it is what gives the “Little House” books their spareness, their directness, their ability to affect us.

When Wilder wrote her first book, she had not yet conceived of the series, but in light of what was ahead, that first novel ends with a different, darker tone: “She was glad that the cosy house, and Pa and Ma and the fire-light and the music, were now. They could not be forgotten, she thought, because now is now. It can never be a long time ago.”

The character of Pa gradually grows more realistic and less mythic as Laura grows up. In the early books, he is tall and powerful, merry and carefree, but in On the Banks of Plum Creek, when grasshoppers destroy the Ingalls’s crop—indeed, every living thing on the prairie—Laura begins to see his vulnerability. Wilder’s fictional descriptions of her father’s financial recklessness always stress his generosity (Pa is unable to resist buying presents for his wife and children or giving his last few dollars to the fund for a church bell) and never suggest that his decisions might have been unwise. (In her letters, Wilder was more straight-forward, writing to her daughter in 1937, while working on By the Shores of Silver Lake: “Interest was high. A man once in debt could stand small chance of getting out…. Pa was no businessman. He was a hunter and trapper, a musician and poet.”) But gradually the crop failures, illnesses, and hardships take their toll on Pa, and Laura begins to perceive the weight of the burden upon him, and on the family.

Apart from an early, unpublished manuscript, “Pioneer Girl,”3 Wilder never wrote about her family’s year in Burr Oak, Iowa. Her parents managed a hotel there, and Laura and Mary (then ten and twelve) waited on tables, made beds, and washed dishes. (She effectively revised this episode out of her life in Little Town on the Prairie: Ma tells her husband, “Charles, I won’t have Laura working out in a hotel among all kinds of strangers,” and Pa replies, “Who said such a thing? No girl of ours’ll do that, not while I’m alive and kicking.”) Her baby brother, Freddie, had just died; the family moved from rented room to rented room, beset by creditors; and a wealthy woman in Burr Oak offered to adopt Laura away from her impoverished family as her own child. Mary contracted the lengthy illness that would eventually blind her—probably scarlet fever followed by meningitis. Freddie’s death and Mary’s illness were traumas that Wilder acknowledged only in the most subdued way. Wilder’s daughter, in an essay published after her death in A Little House Sampler, was more candid: “[Mary] went blind, and that ended everything. In a way, it was an ending for Grandpa and Grandma, too. Mama told me once that they were never quite the same after Mary went blind.”

In letters to her daughter discussing the structure of the novel By the Shores of Silver Lake, Wilder rejected the idea of opening that novel with an account of the true state of affairs, including the tragedy of her sister’s illness:

It would begin with a recital of discouragements and calamities such as Mary’s sickness & blindness. I don’t like it!…

The readers must know all that but they should not be made to think about it.

Her solution was indirection. Mary’s blindness is stated as a fact; her illness is not dramatized in any way: it happens between the end of Plum Creek and the beginning of Silver Lake—off-screen, as it were. The passage that presents Mary’s illness seems designed to keep under control the scale of the narrator’s feeling about the tragedy:

The doctor had come every day; Pa did not know how he could pay the bill. Far worst of all, the fever had settled in Mary’s eyes; and Mary was blind….

Her beautiful golden hair was gone. Pa had shaved it close because of the fever, and her poor shorn head looked like a boy’s. Her blue eyes were still beautiful, but they did not know what was before them, and Mary herself could never look through them again to tell Laura what she was thinking without saying a word.

Compare the plainness of this description of Mary’s blindness to the flowery passage from that famous nineteenth-century American novel about a family of sisters, Little Women:

The flowers were up fair and early, and the birds came back in time to say good-bye to Beth…. With tears and prayers and tender hands, mother and sisters made her ready for the long sleep that pain would never mar again—seeing with grateful eyes the beautiful serenity that soon replaced the pathetic patience that had wrung their hearts so long, and feeling with reverent joy, that to their darling death was a benignant angel—not a phantom full of dread.

By the Shores of Silver Lake and The Long Winter form the tragic center of Wilder’s sequence, as Pa gradually yields the role of heroic provider to Laura’s future husband, Almanzo, and Laura herself takes on the steely determination of her mother to help provide for the family. In the climactic moments of The Long Winter, Wilder dramatizes what must have been the horrific situation of a family of six: confined by blizzards for days at a time to a house consisting of two rooms and an attic, without indoor plumbing of any kind. Her father, for the first time in their lives, loses control:

Suddenly he shook his clenched fist at the northwest. “Howl! blast you! howl!” he shouted. “We’re all here safe! You can’t get at us! You’ve tried all winter but we’ll beat you yet! We’ll be right here when spring comes!”

Pa wants to ride off on a suicidal mission to search the prairie for a cache of wheat that might save them all from starvation, but Ma, reaching her own breaking point, forbids him to go. It is Almanzo and a friend who set off with horses and sled, find the food, and rescue the settlers.

In Little Town on the Prairie, and These Happy Golden Years, Laura becomes a wage-earner, sewing for twelve hours a day in the summer and teaching school in the winter so that the family can afford to send Mary to a college for the blind. Again, it is Almanzo, not Pa, who comes on weekends to fetch Laura from her grim lodgings miles away from home; wooing her on the beautiful horses he drove to find the winter wheat. Horses occupy a singular place in these novels. In Plum Creek, Laura weeps when Pa trades his Indian ponies for oxen to plow the fields. In Silver Lake, she rides her cousin’s Indian pony bareback:

Everything smoothed into the smoothest rippling motion. This motion went through the pony and through Laura and kept them sailing over waves in rushing air. Laura’s screwed-up eyes opened, and below her she saw the grasses flowing back. She saw the pony’s black mane blowing, and her hands clenched tight in it. She and the pony were going too fast but they were going like music and nothing could happen to her until the music stopped.

Almanzo’s horses, Prince and Lady, give her a sense of freedom, strength, and power. The scenes in These Happy Golden Years in which Almanzo lets Laura drive his horses, a task Pa has never trusted her with, become emblematic, finally, of maturity and physical intimacy.

Given Wilder’s determination to rewrite her life as a progressive tale of survival, it is hardly surprising that she never attempted to publish a manuscript she wrote sometime in the 1930s, titled “The First Three Years and a Year of Grace,” about the early years of her marriage. We know from a letter Wilder wrote to her daughter in 1937 that the manuscript was only a “framework,” and that she “wondered if it would be worth while to write the one grown-up story of Laura and Almanzo to sort of be the cap-sheaf of the…children’s novel.”

But The First Four Years (published only in 1971 with some revisions by Roger MacBride, Rose Wilder Lane’s literary executor and heir) clearly could not have been transformed into a triumphant closure for the series. The events it describes—years of illness, debt, the death of the Wilders’ infant son, and the crippling of Almanzo—are too devastating. The manuscript was found among Lane’s papers after her death; Lane never sought to publish it. Nevertheless, although it is shorter than the other books and more closely autobiographical, it is hardly just a “framework.” The First Four Years affords a fascinating glimpse of Wilder’s raw material, including scenes that were significantly altered in These Happy Golden Years. Here dismay over poverty and loss are acknowledged, as well as the initial delight at her adult independence. Almanzo, whom she calls Manly, has bought his wife her own pony and the newlyweds go on long horseback rides. She writes, wistfully, “It was a carefree, happy time, for two people thoroughly in sympathy can do pretty much as they like.” “Thoroughly in sympathy” is about as direct as Wilder could be about her feelings about her husband, but she graphically describes how she abandoned their home to the fire that destroyed it:

Taking…Rose by the hand, she ran out and dropped on the ground in the little half-circle drive before the house. Burying her face on her knees she screamed and sobbed, saying over and over, “Oh, what will Manly say to me?” And there Manly found her and Rose, just as the house roof was falling in.

But here, too, as with Mary’s blindness, Wilder does not acknowledge the physical and emotional cost of her husband’s illness. She writes that “there was a struggle to keep Manly’s legs so that he could use them…. but gradually they improved until he could go about his usual business if he was careful.” Rose Wilder Lane wrote that the true effects of Almanzo’s illness were grave: “It left him partially paralyzed for some years, so all he could do was hunt for odd jobs.” In 1937, Almanzo Wilder wrote to his daughter, “My life has been mostly disappointments.”

3.

According to William Holtz, the author of The Ghost in the Little House, Rose Wilder Lane’s life was full of the cosmopolitan sophistication her parents never knew. In 1904, at the age of seventeen, she left home to work as a telegraph operator and discovered a taste for big-city life in Kansas City and San Francisco. Her early marriage to Gillette Lane, an itinerant journalist and confidence man, soon ended in divorce, but Lane herself became a popular writer for the San Francisco newspapers, publishing fiction, interviewing celebrities (Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford), and writing biographies of Henry Ford and Herbert Hoover. She knew many of the intellectuals of the day (becoming close friends with Dorothy Thompson) and, after World War I, traveled widely throughout the Middle East and Eastern Europe, writing popular travelogues. But by the late 1920s, Lane’s literary career had stalled, and she returned to her parents’ home in Mansfield, Missouri, intending to visit for a year or so. She stayed eight years, and her diaries are filled with despairing allusions to her writer’s block and with notes about the editorial help she was providing to her mother, who had begun to write the “Little House” books.

Holtz has largely depended on the diaries and correspondence which Lane kept during this period, and which are housed in the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library in West Branch, Iowa, to advance his theory that it was Lane who secretly wrote her mother’s “Little House” books. Holtz suggests that Laura Ingalls Wilder produced fragmentary and disorganized handwritten memoirs which were then rendered publishable by the professional writer, Lane. He has relied so heavily on Lane’s letters and notes that her own words are virtually the only documentary evidence he uses to describe the working relationship of Lane and Wilder (whom he refers to as “Mama Bess” throughout). Of Wilder’s first book:

Mama Bess brought her more manuscript pages to be worked into the juvenile for Knopf….

Rose was working on a short story of her own at the moment and set her mother’s pages aside until she had finished…. Three more days of work produced a clean copy, and as the last pages came out of the typewriter Mama Bess arrived to read the final chapters.

And this is how he accounts for the composition of Wilder’s third novel, Little House on the Prairie: “Mama Bess called it her Indian story, Rose entitled it ‘High Prairie’ as she worked on the manuscript during five weeks in May and June, and in time it would be published as Little House on the Prairie.” Holtz’s footnotes refer the reader to dates of Lane’s unpublished diaries and correspondence.

It is of course difficult to assess the accuracy of either Holtz’s claims or Lane’s interpretation of events. But the main problem with Holtz’s theory of Lane’s authorship is that so much manuscript evidence contradicts it. Aside from a brief discussion of one chapter of Little Town on the Prairie, the only textual comparison Holtz provides in The Ghost in the Little House is a seven-page appendix, which compares passages from one of Wilder’s handwritten manuscripts—again, that of Little Town on the Prairie—with the published text. In this appendix, Holtz writes, “To appreciate Rose Wilder Lane’s contribution to her mother’s books, one must simply read her mother’s fair-copy manuscripts in comparison with the final published versions.” Holtz’s assumption that the handwritten manuscripts are Wilder’s only contribution to her books and that the final published texts represent Lane’s work alone is astonishing. What is even more astonishing than Holtz’s simplistic conclusion is the willingness with which it has been accepted by virtually every reviewer of his book. It is now widely and unjustly assumed that Laura Ingalls Wilder is not the true author of her books.

It is apparent in both the letters between mother and daughter and the typescript versions of the texts that there was a complicated collaboration between the two women. The dimestore tablets on which Wilder wrote her books in pencil are owned by several libraries around the country, while the Herbert Hoover Library owns some typed manuscripts of the “Little House” books that were produced either by Rose Wilder Lane or by a typist (Wilder herself did not own a typewriter). I have examined microfilm copies of Wilder’s handwritten manuscripts of Little House on the Prairie and Little Town on the Prairie and copies of her correspondence and revisions that are part of the typescript manuscripts of By the Shores of Silver Lake and The Long Winter and have found that all of these manuscript materials include extensive corrections and revisions in Wilder’s own hand.

Some stages of the revised typed manuscripts may have been lost. (For instance, only the original manuscript and galley proofs of Little Town on the Prairie are known to exist; the typescripts are missing.) And as William Anderson, a scholar who has written extensively on the Wilder manuscripts, has suggested, any full understanding of the extent to which Lane revised her mother’s work is highly unlikely.4 But it seems obvious from her handwritten manuscripts that Wilder is the author of her own books, and that she had a very active hand in revising them.

Wilder never graduated from high school, and Lane seems to have simplified, clarified, and modernized her mother’s old-fashioned and sometimes clumsy diction, spelling, and grammar. She also seems to have added transitions to the beginning of the books and to some of their chapters. She may also have revised passages, adding or expanding dialogue, and changed the order of some chapters for dramatic effect. But this is not certain, since we can never know much about the communication between Wilder and Lane while the two women were living next door to each other, for the first five years that Wilder was working on her series.

The typescript of The Long Winter is full of Wilder’s revisions. In the chapter “Pa Goes to Volga,” which describes how the men of De Smet traveled down the train tracks on a handcar to clear the snow, Wilder has crossed out some of the language her daughter had put in to describe steam rising from the men’s mouths. Wilder wrote in the margin, “I don’t like this, Laura could not possibly have seen steam from their faces.” She also penciled in corrections concerning the layout of De Smet and drew diagrams of the handcar and its handlebars. Aside from her corrections on the typescript itself, she handwrote an additional thirteen pages of revisions, including the entire text of the poem, “Old Tubal Cain” (see page 229 of The Long Winter) and these instructions:

Don’t cut the hymn I had Ma sing to Grace. I forget where I placed it—“I will sing you a song of that beautiful land, the far away home of the soul / Where no storms ever beat on that glittering strand / While the years of eternity roll” and the rest of it. A land where storms never beat would have been thought of with longing. It has a wailing tune too. The kind Ma sang when she did sing. We must show the effect the winter was having. It nearly broke Ma down when she sang of the land where there were no storms. And Pa when he shook his fist at the wind. Don’t leave that out. We have shown that they both were brave, let’s show what the winter nearly did to them.

And so the novel does: Ma’s hymn and Pa shaking his fist are in the published version.

That we can never know how Lane’s typed manuscripts were actually produced or what control Wilder had over them is something that Holtz never acknowledges. While Holtz is right to interpret Lane’s diaries and the letters that were exchanged between Wilder and Lane as indicating that the daughter went over each manuscript, and edited them, these documents make clear that they quarreled over the tone and direction of the books. Characteristically, in 1939, Wilder wrote to her daughter about the manuscript of The Long Winter, “I expect you will find lots of fault on it, but we can argue it out later.”

In “Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: The Continuing Collaboration,” an essay published (Summer 1986) in South Dakota History, William Anderson describes the evolution of Farmer Boy from Wilder’s pencil draft to Lane’s second typed revision. Noting that Lane’s first typed copy and perhaps additional versions of Wilder’s have never been found, he explains what Holtz should have made clear:

No scrap of correspondence between mother and daughter exists to suggest how Rose Wilder Lane’s first editing of her mother’s draft manuscript developed. With Wilder and Lane living less than a mile apart on the farm, it is obvious—and evident from Lane’s diary entries—that discussions of technique and revisions were accomplished via the telephone or over the teacups at Rocky Ridge farmhouse.

Lane’s own writing career progressed from popular biographies to serial fiction to ponderous tomes on libertarian economics. She eventually became a kind of political crank, with a deep dislike of Roosevelt and the New Deal, refusing a ration card during World War II, and, in her old age, telling tall tales about meetings with Mussolini and Trotsky. (Her belief in self-reliance and the danger of big government seems to have cropped up in Wilder’s work, particularly in the “Fourth of July” chapter in Little Town on the Prairie, one of the few passages Holtz discusses in detail.) At the end of her life she was living off the royalties of her mother’s work.

As Wilder was beginning work on the “Little House” books, Lane herself attempted to make use of the stories she had heard from her mother and grandparents about their pioneering years. In 1932, the year Little House in the Big Woods was published, Lane wrote a novella based on these stories and sold it as a serial to the Saturday Evening Post, angering her mother. The central characters’ names were “Charles” and “Caroline,” the names of Wilder’s parents and Wilder’s characters.

To judge by their letters, Lane’s influence on her mother’s writing career was largely shaped by Wilder’s insecurities and irritations and by Lane’s desire to become competent in her mother’s eyes. In 1924, Lane wrote to her mother about an article Wilder was writing for Country Gentleman:

You must listen to me…. If you don’t do what I tell you to, you must at least have good hard reasons for not doing it…and be able to show how and where and why your work is better because you didn’t do as I said…. Just because I was once three years old, you honestly oughtn’t to think that I’m never going to know anything more than a three-year-old. Sometime you ought to let me grow up.

In her letters and journal entries, Lane constantly veers between self-contempt and self-assurance. The possibility that she may be an unreliable narrator of her own life never seems to occur to Holtz. He relies uncritically on Lane’s words.

Holtz also insists that Lane was a far better writer than her mother. Comparing the letters of daughter and mother, he proclaims that “nothing could be more different from Rose’s easy and vigorous style than her mother’s pedestrian prose,” a statement that is not borne out by the letters he quotes or by those Wilder wrote to her husband from San Francisco, which were published in 1974 in West from Home: Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco 1915. Wilder’s “pedestrian prose” is, in fact, descriptive and lyrical, just as it is in her novels:

All night and all day we can hear the sirens on the different islands and headlands, and the ferries and ships at anchor in the bay keep their foghorns bellowing. We can not see the bay at all nor any part of San Francisco except the few close houses on Russian Hill. The foghorns sound so mournful and distressed, like lost souls calling to each other through the void. (Of course, no one ever heard a lost soul calling, but that’s the way it sounds.)

Lane’s own fiction is not much read today. It contains many of the sentimental and stylistic clichés of popular fiction from the Thirties and Forties. While it’s at least conceivable that Lane could have produced “shining fiction…made from her mother’s tangle of fact,” as Holtz claims, she certainly did not produce “shining fiction” herself. “Let the Hurricane Roar,” the novella she published in 1932 in the Saturday Evening Post, is hackneyed and shapeless, with lifeless characters. In it the grasshopper plague that is described in On the Banks of Plum Creek serves as the occasion for this maudlin display: “To her surprise, she began to cry. Her mouth writhed uncontrollably and tears ran from her eyes…. Tears brimmed his raw lids. He drew her against him where he sat on the bench. She felt the sob shake his body.” Here is the same scene in Plum Creek:

[Pa] put his elbows on the table and hid his face with his hands. Laura and Mary sat still. Only Carrie on her high stool rattled her spoon and reached her little hand toward the bread. She was too young to understand.

“Never mind, Charles,” Ma said. “We’ve been through hard times before.”

Laura looked down at Pa’s patched boots under the table and her throat swelled and ached. Pa could not have new boots now.

It is clear that in the collaboration of writer and editor, Wilder and Lane, they combined their strengths and minimized their weaknesses. But it is also clear that, of the two, Wilder was the genuine writer.

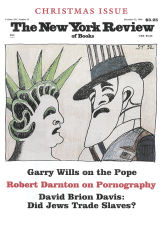

This Issue

December 22, 1994

-

1

Among others, Patricia Limerick in The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (Norton, 1988) and Richard White in ‘It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own‘ (University of Oklahoma Press, 1991) have explored the many ways in which pioneers were failures, exploiting the land with unsuccessful methods of farming, ranching, or mining, and then abandoning it. ↩

-

2

In a June 1993 essay on Wilder in Booklist, Michael Dorris, the novelist and founder of the Native American Studies Program at Dartmouth College, described his fondness for the “Little House” books as a boy but recently decided not to read them aloud to his daughters because of what he labeled their “objectionable parts.” He found the opening of Little House in the Big Woods particularly objectionable: “Weren’t we forgetting the Chippewa branch of my daughters’ immediate ancestry, not to mention the thousands of resident Menominees, Potawatomis, Sauks, Foxes, Winnebagos, Ottawas who inhabited mid-nineteenth-century Wisconsin, as they had for many hundreds of years.” In fact, apart from this fairy-tale beginning, Wilder describes many encounters with Indians in her books. Ma reacts to all Indians with fear and disgust, but Pa respects their knowledge of the land and Laura is fascinated by their freedom from the very constrictions she resents. ↩

-

3

Several drafts are in the Hoover Presidential Library. ↩

-

4

Anderson explores the literary relationship between Wilder and Lane in far greater detail than Holtz in two essays: “The Literary Apprenticeship of Laura Ingalls Wilder,” South Dakota History (Winter 1983) and “Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: The Continuing Collaboration,” South Dakota History (Summer 1986). ↩