In response to:

The Abuse of McNamara from the May 25, 1995 issue

To the Editors:

Robert McNamara’s laudable goal, to put the past behind us, will only be achieved by understanding history, not by rewriting it. Unfortunately, both McNamara’s memoir and Draper’s review [“The Abuse of McNamara,” NYR, May 25] have failed us. Even more than McNamara, Draper misrepresents how we went to war with North Vietnam, by belittling the provocativeness of the 1964 Tonkin Gulf incidents.

To be sure, Draper notes that the second “attack,” the one which provoked U.S. retaliation, “was dubious, if not fictitious.” (McNamara still claims that “the second attack appears probable but not certain”; almost all historians now agree with Stanley Karnow that it “never happened.”)

But where did Draper ever read that (in his words) the US destroyers under patrol in the Tonkin Gulf “stayed more than twenty-five miles off the North Vietnamese coast to protect themselves from attack?” Even McNamara concedes that “the closest approach to North Vietnam was set at eight miles to the mainland and four miles to the offshore islands,” and that the closest actual approach was no “closer than five miles to the offshore islands.”

The ships were on an electronic intelligence spy mission, seeking to obtain prints from North Vietnamese radars. Thus their orders were to simulate attacks on North Vietnamese military bases, in order to “stimulate…electronic reaction,” i.e. induce them to turn their radars on. Far from being twenty-five miles from the islands attacked during the same period by South Vietnamese patrol boats, the destroyers were ordered to focus on this area, repeatedly sailing in toward shore with their own fire-control radars turned on, as if preparing to shoot.

Thus Draper’s factual error has the effect of minimizing how provocative was the destroyers’ mission. It also obscures how deceptive were McNamara’s assurances to Congress in 1964 that this was “a routine patrol,” and in 1968 that “provocative actions were avoided.” We have recently seen a media debate about McNamara’s alleged “silence” about his own doubts after 1967. But at the 1968 hearing he was most vociferous in rebutting other doubters, including those who (in his words) had “mistakenly assumed that there is serious doubt as to whether the ‘second’ Tonkin Gulf attack in fact took place.” At least three of the senators who heard him in 1968 (Morse, Cooper, and Gore) complained, justifiably, that they had been misled.

In his memoir McNamara now admits that “we were wrong, terribly wrong”; but he is still trying to sound right about Tonkin Gulf. He certainly strives to defend more than to explain or atone for his crucial misrepresentations that led in 1964 and 1968 to the passage and continuance of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. His apologies, over and over, are for debatable errors of policy; but he still refuses to admit, let alone give us insight into, most of these fatal, uncontrovertible misstatements of fact.

Thus it is hard to agree with Theodore Draper that McNamara has now “paid his debt.”

Peter Dale Scott

English Department

University of California

Berkeley, California

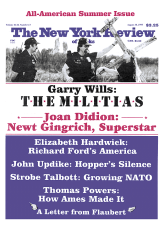

This Issue

August 10, 1995