Silence fell. Pitilessly illuminated by the lamplight, young and plump-faced, wearing a side-buttoned Russian blouse under his black jacket, his eyes tensely downcast, Anton Golïy began gathering the manuscript pages that he had discarded helter-skelter during his reading. His mentor, the critic from Red Reality, stared at the floor as he patted his pockets in search of some matches. The writer Novodvortsev was silent too, but his was a different, venerable, silence. Wearing a substantial pince-nez, exceptionally large of forehead, two strands of his sparse dark hair pulled across his bald pate, gray streaks on his close-cropped temples, he sat with closed eyes as if he were still listening, his heavy legs crossed and one hand compressed between a kneecap and a hamstring. This was not the first time he had been subjected to such glum, earnest rustic fictionists. And not the first time he had detected, in their immature narratives, echoes—not yet noted by the critics—of his own twenty-five years of writing; for Golïy’s story was a clumsy rehash of one of his subjects, that of The Verge, a novella he had excitedly and hopefully composed, whose publication the previous year had done nothing to enhance his secure but pallid reputation.

The critic lit a cigarette. Golïy, without raising his eyes, was stuffing his manuscript into his briefcase. But their host kept his silence, not because he did not know how to evaluate the story, but because he was waiting, meekly and drearily, in the hope that the critic might perhaps say the words that he, Novodvortsev, was embarrassed to pronounce: that the subject was Novodvortsev’s, that it was Novodvortsev who had inspired the image of that taciturn fellow, selflessly devoted to his laborer grandfather, who, not by dint of education, but rather through some serene, internal power wins a psychological victory over the spiteful intellectual. But the critic, hunched on the edge of the leather couch like a large, melancholy bird, remained hopelessly silent.

Realizing yet again that he would not hear the hoped-for words, and trying to concentrate his thoughts on the fact that, after all, it was to him and not Neverov that the aspiring author had been brought for an opinion, Novodvortsev repositioned his legs, inserted his other hand between them, said with a businesslike tone, “Now, then,” and, with a glance at the vein that had swelled on Golïy’s forehead, began speaking in a quiet, even voice. He said the story was solidly constructed, that one felt the power of the Collective in the place where the peasants start building a school with their own means, that, in the description of Pyotr’s love for Anyuta there might be imperfections of style, but one heard the call of spring and of a wholesome lust—and, all the while as he talked, he kept remembering for some reason how he had written recently to this same critic, to remind him that his twenty-fifth anniversary as an author would fall in January, but that he emphatically requested that no festivities be organized given that his years of dedicated work for the Union were not yet over….

“As for your intellectual, you didn’t get him right,” he was saying. “There is no real sense of his being doomed….”

The critic still said nothing. He was a red-haired man, skinny and decrepit, rumored to be ill with consumption, but in reality probably healthy as a bull. He had replied, also by letter, that he approved of Novodvortsev’s decision, and that had been the end of it. He must have brought Golïy by way of secret compensation…. Novodvortsev suddenly felt so sad—not hurt, just sad—that he stopped short and started wiping his lenses with his handkerchief, revealing quite kindly eyes.

The critic rose. “Where are you off to? It’s still early,” said Novodvortsev, but he got up too. Anton Golïy cleared his throat and pressed his briefcase to his side.

“He will become a writer, there’s no doubt about it,” said the critic with indifference, roaming about the room and stabbing the air with his spent cigarette. Humming, with a raspy sound, through his teeth, he drooped over the desk, then stood for a time by an étagère where a respectable edition of Das Kapital dwelt between a tattered volume of Leonid Andreyev and a nameless tome with no binding; finally, with the same stooping gait, he approached the window and drew the blue blind aside.

“Drop in sometime,” Novodvortsev was meanwhile saying to Anton Golïy, who bowed jerkily and then squared his shoulders with a swagger. “When you’ve written something more, bring it on over.”

“Heavy snowfall,” said the critic, releasing the blind. “By the way, today is Christmas Eve.”

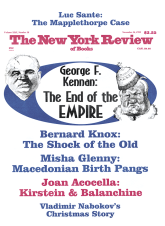

Advertisement

He began rummaging listlessly for his coat and hat.

“In the old days, on this date you and your confrères would be churning out Christmas copy….”

“Not I,” said Novodvortsev.

The critic chuckled. “Pity. You ought to do a Christmas story. New-style.”

Anton Golïy coughed into his fist. “Back home we once had—“ he began in a hoarse bass, then cleared his throat again.

“I’m being serious,” continued the critic, climbing into his coat. “One can devise something very clever…. Thanks, but it’s already—“

“Back home,” Anton Golïy said, “We once had. A teacher. Who. Took it into his head. To do a Christmas tree for the kids. On top he stuck. A red star.”

“No that won’t quite do,” said the critic. “It’s a little heavy-handed for a small story. You can put a keener edge on it. Struggle between two different worlds. All against a snowy background.”

“One should be careful with symbols generally,” glumly said Novodvortsev. “Now I have a neighbor—upstanding man, Party member, active militant, yet he uses expressions like ‘Golgotha of the Proletariat’….”

When his guests had left he sat down at his desk and propped an ear on his thick, white hand. By the inkstand stood something akin to a square drinking glass with three pens stuck into a caviar of blue glass pellets. The object was some ten or fifteen years old—it had withstood every tumult, whole worlds had shaken apart around it—but not a single glass pellet had been lost. He selected a pen, moved a sheet of paper into place, tucked a few more sheets under it so as to write on a plumper surface….

“But what about?” Novodvortsev said out loud, then pushed his chair aside with his thigh and began pacing the room. There was an unbearable ringing in his left ear.

The scoundrel said it deliberately, he thought, and, as if following in the critic’s recent footsteps, went to the window.

Presumes to advise me…. And that derisive tone of his…. Probably thinks I have no originality left in me…. I’ll go and do a real Christmas story…. And he himself will recollect, in print: “I drop in on him one evening and, between one thing and another, happen to suggest, ‘Dmitri Dmitrievich, you ought to depict the struggle between the old order and the new against a background of so-called “Christmas” snow. You could carry through to its conclusion the theme you traced so remarkably in The Verge,—remember Tumanov’s dream? That’s the theme I mean….’ And on that night was born the work which….”

The window gave on a courtyard. The moon was not visible…. No, on second thought, there is a sheen coming from behind a dark chimney over there. Firewood was stacked in the courtyard, covered with a sparkling carpet of snow. In a window glowed the green dome of a lamp—someone was working at his desk, and the abacus shimmered as if its beads were made of colored glass. Suddenly, in utter silence, some lumps of snow fell from the roof’s edge. Then, again, a total torpor.

He felt the tickling vacuum that always accompanied the urge to write. In this vacuum something was taking shape, growing. A new, special kind of Christmas…. Same old snow, brand-new conflict….

He heard cautious footfalls through the wall. It was his neighbor coming home, a discreet, polite fellow, a Communist to the marrow of his bones. With an abstract rapture, a delicious expectation, Novodvortsev returned to his seat at the desk. The mood, the coloring of the developing work were already there. He had only to create the skeleton, the subject. A Christmas tree—that’s where he should start. In some homes, he imagined people who had formerly been somebody, people who were terrified, ill-tempered, doomed (he imagined them so clearly…) who must surely be putting paper ornaments on a fir stealthily cut down in the woods. There was no place to buy that tinsel now, and they don’t heap fir trees in the shadow of Saint Isaac’s any more….

Cushioned, as if bundled up in cloth, there came a knock. The door opened a couple of inches. Delicately, without poking in his head, the neighbor said,

“May I bother you for a pen? A blunt one would be nice, if you have it.”

Novodvortsev did.

“Thank you kindly,” said the neighbor, soundlessly closing the door.

This insignificant interruption somehow weakened the image that had already been ripening. He recalled that, in The Verge, Tumanov felt nostalgia for the pomp of former holidays. Mere repetition wouldn’t do. Another recollection flashed inopportunely past. At a recent party some young women had said to her husband, “In many ways you bear a strong resemblance to Tumanov.” For a few days he felt very happy. But then he made the lady’s acquaintance, and the Tumanov turned out to be her sister’s fiancé. Nor had that been the first disillusionment. One critic had told him he was going to write an article on “Tumanovism.” There was something infinitely flattering about that “ism,” and about the small “t” with which the word began in Russian. The critic, however, had left for the Caucasus to study the Georgian poets. Yet there had been pleasant occurrences as well. For instance, a list like “Gorky, Novodvortsev, Chirikov…”

Advertisement

In an autobiography accompanying his complete works (six volumes with portrait of the author), he had described how he, the son of humble parents, had made his way in the world. His youth had, in reality, been happy. A healthy vigor, faith, successes. Twenty-five years had passed since a plump journal had carried his first story. Korolenko had liked him. He had been arrested now and then. One newspaper had been closed down on his account. Now his civic aspirations had been fulfilled. Among beginning, younger writers he felt free and at ease. His new life suited him to a T. Six volumes. His name well known. But his fame was pallid, pallid….

He skipped back to the Christmas-tree image, and suddenly, for no apparent reason, remembered the parlor of a merchant family’s house, a large volume of articles and poems with gilt-edged pages (a benefit edition for the poor) somehow connected with that house, the Christmas tree in the parlor, the woman he loved in those days, and all of the tree’s lights reflected as a crystal quiver in her wide-open eyes when she plucked a tangerine from a high branch. It had been twenty years ago or more—how certain details stuck in one’s memory….

He abandoned this recollection with chagrin and imagined once again the same old shabby fir trees that, at this very moment, were surely being decorated…. No story there, although of course one could give it a keener edge…. Emigrés weeping around a Christmas tree, decked out in their uniforms redolent of mothballs, looking at the tree and weeping. Somewhere in Paris. Old general recalls how he used to smack his men in the teeth as he cuts an angel out of gilded cardboard…. He thought about a general whom he actually knew, who actually was abroad now, and there was no way he could picture him weeping as he knelt before a Christmas tree….

“I’m on the right track, though,” Novodvortsev said aloud, impatiently pursuing some thought that had slipped away. Then something new and unexpected began to take shape in his fancy—a European city, a well-fed, fur-clad populace. A brightly lit store window. Behind it an enormous Christmas tree, with hams stacked at its base and expensive fruit affixed to its branches. Symbol of well-being. And in front of the window, on the frozen sidewalk—

With triumphal agitation, sensing that he had found the necessary, one-and-only key, that he would write something exquisite, depict as no one had before the collision of two classes, of two worlds, he commenced writing. He wrote about the opulent tree in the shamelessly illuminated window and about the hungry worker, victim of a lockout, peering at that tree with a severe and somber gaze.

“The insolent Christmas tree,” wrote Novodvortsev, “was afire with every hue of the rainbow.”

—1928, Translated from the Russian by Dmitri Nabokov

This Issue

November 16, 1995