In abandoning India and Anglo-Indian subjects, Ismail Merchant and James Ivory lost the dry and delicate touch that made Shakespeare Wallah and Heat and Dust so memorable. However, they have gained a vast following with glossy films of E.M. Forster’s low-key novels, in which they vulgarize the issues and overdecorate the sets. Their Room with a View, Maurice, and Howards End offer souped-up versions of Edwardian life: flower-showy gardens, fancy horses from the royal stables, and more mahogany paneling than the Connaught Hotel—“Ralph Lauren’s England,” someone said. It all evokes Galsworthy rather than Forster.

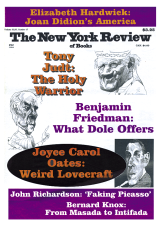

The team has recently moved on to biography, to two very dull films about two very great men, Jefferson and Picasso. Illustrious achievements do not interest Merchant and Ivory so much as sexual relationships, especially ones to which they can give a prurient, voyeuristic spin. Jefferson in Paris appalled Jeffersonians by portraying him—on highly controversial evidence—as the philandering lover of a black slave girl. Surviving Picasso is no less dismaying for its attempt to demonize the artist for his supposedly manipulative and sadistic treatment of Françoise Gilot, his mistress from 1943 to 1953, and thus attract a feminist audience.

Surviving Picasso draws on an even more controversial source than the Jefferson movie. It is supposedly based on Arianna Stassinopoulos’s hostile scissors-and-paste biography Picasso: Creator and Destroyer, a book which Ivory claims to be “marvelously detailed and researched,” although, as he must surely know, scholars gave it universally terrible reviews because it is nothing of the sort. (One scholar, Lydia Gasman, had her lawyers discuss with Stassinopoulos’s publisher a possible suit against the author for plagiarism.) In fact, Ivory’s film is all too evidently inspired by Françoise Gilot’s revelatory Life with Picasso and other memories which, to her eternal regret, she allowed Stassinopoulos to share. Merchant and Ivory had originally approached Françoise Gilot in the hope of obtaining film rights; they were met with an adamant refusal, and so had no option but to sign up Stassinopoulos and pretend that their film is based on her book.

Deny it though they might, Surviving Picasso follows Françoise Gilot’s pages, except that it trivializes them. After reading the writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s simplistic, soap-opera-ish script, Françoise and her son, Claude, who administers the Picasso estate, were horror-stricken and took legal steps to stop the film from being made. Claude was not able to do so, but he managed to refuse Merchant and Ivory permission to show any of Picasso’s works—an action that Ivory likes to impute to Claude’s supposed rivalry: “People in France say that…Claude Picasso himself wanted to make a film about his father so that we were really coming on his territory.” There is no truth whatsoever to this assertion. Françoise thinks they would have won their case if they had decided to proceed with it, but the process would have been too long and costly. She managed to have her name, Gilot, removed from the film, but could not stop Merchant and Ivory from using voice-over narration purporting to be hers.

On being denied permissions and assistance from reputable sources, anyone seriously interested in Picasso’s art would have shelved plans for this questionable project. But Ivory, who directed (Merchant limited himself to producing), decided to go ahead using parodic doodles, garish daubs, and assemblages by people who had no idea what Picasso was about. One of the painters, Merchant and Ivory’s neighbor, Bruno Pasquier-Desvignes, is under no illusion about their badness: “Can you imagine a critic in front of these things?” he said. “He’s going to have a nervous breakdown.” Some of these daubs are apparently by the director himself.

The makers of the film have tried to play down their deceptive use of fakes. “We didn’t want to overload the film with painting,” says Merchant. Ivory, on the other hand, claimed on The Charlie Rose Show that “the film is full of art.” In fact, except for brief appearances of the right Matisse and the wrong Braque, and a Cézanne improbably hung above a bed, the film is full of nothing but schlock, which people who don’t know better (and that includes critics) may take for the real thing. As Ivory said in a recent interview: “Most people wouldn’t know what was authentic or not.”* Besides demonizing the man, the film effectively defiles the work. This is the more shocking coming from someone who was once a painter, who claims to have had a lifelong admiration for Picasso and sees his film as a tribute.

Surviving Picasso relies throughout on fakes. Even the actors who impersonate the artist and his wives and mistresses bear the same resemblance to the real thing that the paintings in the film do to originals. People who never met Picasso think that Anthony Hopkins, who plays him in the movie, looks very like him. He doesn’t. Nor has Hopkins’s wish to have “gotten the rhythm of the man,” as he put it to an interviewer, been fulfilled. In fact Hopkins bears as much resemblance to Henry Moore as he does to Picasso. Instead of coming across as the most Spanish of Spaniards, he looks very English and sounds faintly Welsh; a sardonic, skittish don whose teasing of girls gets a bit out of hand. There are occasional echoes of Hannibal Lecter, but they hardly suggest the “magnetic appeal [and] a certain charisma” that Merchant hoped to capture. Might this failure explain why the producer held up Hopkins’s payments? “I was going to sue them,” the star told the press. “I vowed I would never work with them again…. I think it’s good to blow the whistle on them.” His protest worked: he got paid.

Advertisement

Picasso’s magnetism resided in the huge brown pupils of his eyes, which he used to astonishing effect. He looked at drawings with such intensity that Leo Stein wondered whether there would be anything left on paper; in old age his eyes would become a surrogate sexual organ. Hopkins tries to duplicate the intensity of Picasso’s gaze; he even wears contact lenses that turn his blue eyes brown. All he can muster is an arch twinkle or a sinister glint, as in an overdramatized, eerily lit owl-and-pussycat sequence where Hopkins grabs Françoise (Natascha McElhone) and forces her to watch as a large owl sweeps down on a stray cat and carries it off. “Not the way it was,” said Françoise when told of this. (She refuses to see the film.) The trouble is that Hopkins, like Boris Karloff, reverberates with old roles (in this case with The Silence of the Lambs) much as Stradivarius’s violins are said to reverberate with old melodies. (It was apparently James Lord, author of Picasso and Dora and the only friend of Picasso’s to have given Merchant and Ivory any support, who recommended Hopkins. Lord took against Picasso over the Hungarian revolution and has had it in for him ever since.)

Picasso was a misogynist, but then so is virtually every Andalusian male. In the circumstances, it is foolish to judge an artist from another age and another culture—be he Picasso or that other misogynist, Rembrandt—by the light of today’s cant. Nor should we ignore the ambivalence that is at the root of Picasso’s character. Whatever one says about him, good or bad, the converse will almost always apply.Picasso was compounded of antitheses. He could be infinitely gregarious yet reclusive, penny-pinching yet generous, wise yet foolish, tough yet vulnerable, virtuous yet wicked; and although he was a great hero in his studio, he was anything but a hero in the face of authority. The same with his misogyny: Picasso could also be affectionate, gentle, and tender. In his greatest portraits, these different perceptions fuse into images that are at the same time intensely poignant and intensely disturbing. Therein lies their power—a nefarious power in the eyes of the politically modish, though why they have singled out Picasso as the quintessence of male chauvinist piggery I have never been able to fathom. His conduct pales if we compare it to Matisse’s failure to come to the assistance of his wife and daughter when the Gestapo arrested them in 1944.

The film is not so much about Picasso as it is about Françoise. So much of the emphasis is on her role as victim—someone to whom things happen. In fact Françoise was the least submissive, least neurotic, and least vulnerable of the women in the artist’s life, and to that extent less of an inspiration. The paintings in which she figures (I hesitate to say portraits) pay tribute to her youthful beauty and cool serenity, but they seldom manifest any of the angst, ambivalence, or sexual fixation that give the paintings of her predecessors—Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar—such power. In her book Françoise makes it very clear that she knew how to look after herself and was not prepared to play the sacrificial role that Picasso usually imposed on his women. The fact that she published an outspoken memoir is a measure of her self-confidence as well as her resentment and defiance. For, as she well knew, Picasso treasured his privacy to an extent bordering on paranoia. When he failed to have her book withdrawn, he vented his vengeance on their two children, Claude and Paloma, who were banished forever from his sight.

Advertisement

Picasso complained of the book that the fascinating discourses on art that Françoise put into his mouth (they are all in quotes) were not colloquial enough—too pedagogical and too full of long words, like “architectonic,” which he could not have used, he said, because he did not understand them. True, the pedagogical tone is hardly Picassian, but the murderous quips, baroque complaints, and outrageous paradoxes that she quotes have a very authentic ring. Here we should remember that the artist hoped that Françoise would function as his recording angel. Her recapitulations of his views on painting did not, to my mind, upset Picasso so much as her revelations of the childish tantrums and superstitions that were the converse of his genius.

James Ivory allows that Surviving Picasso is “really the story of,…I hate to say this, but a kind of starstruck young girl who falls in love with a great genius”; and that is how Natascha McElhone, who makes her screen debut as Françoise, plays her. This is to underrate Françoise. McElhone radiates a long-suffering sweetness, but too little of the sharpness, intelligence, and ambition which enabled her to “survive” Picasso. Nor do her predecessors in the artist’s life, Dora Maar and Marie-Thérèse Walter, fare much better. Dora’s intensity, which ended by frightening Picasso, and Marie-Thérèse’s pneumatic sexuality, which continued to obsess him long after they broke up, are hardly evoked. By contrast, the artist’s first wife, the Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova, is an absurd and hilarious caricature; and the flashbacks in which she figures are sheer Monty Python. But then, as Merchant confided to Charlie Rose, “an Indian producer is not just an Indian producer, [he is] a producer who…can do anything”: the Indian rope trick, the vanishing trick, the balls-in-the-air trick. “Jim [Ivory] still has not…quite understood how many things I’m capable of handling,” Merchant says. The Monty Python flashbacks include a riotous Ballets Russes dinner at which epicene dancers dressed as peacocks prance around, while Diaghilev leers, society women preen, and Hopkins toys with what look like women’s breasts made of Jello. Evidently one of their rope tricks. Besides this dinner party, I enjoyed that excellent actor, Peter Eyre, in the role of Sabartes, Picasso’s Catalan curmudgeon of a secretary. “I thought of Judith Anderson,” Eyre told me, “and gave it everything I’ve got.” He was right. Sabartes can indeed be seen as Picasso’s Mrs. Danvers.

Films about great artists are a benighted genre in that they usually sacrifice art to a sentimental or sensational story line. And then, the creative process is too slow, private, and monotonously painstaking to be entertaining, let alone cinematic. The more over-life-size the performance, the less credible the artist. Who could possibly believe in Charles Laughton as Rembrandt; José Ferrer as Toulouse-Lautrec; George Sanders, Anthony Quinn, or Donald Sutherland as Gauguin; Charlton Heston as Michelangelo; Anthony Quinn or Kirk Douglas as van Gogh?

Minor or fictional artists fare better: for instance, Isabelle Adjani as Camille Claudel, or Alec Guinness as the painter in Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth, which had the help of some remarkably credible paintings made for the film by John Bratby. I have not seen Gösta Ekman’s 1978 comedy The Adventures of Picasso, with two Swedish drag queens playing Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, but it, too, has been described as Pythonesque. Anyone who wants to have an idea of what Picasso was like and how he worked can do so in Henri Clouzot’s ingenious Le Mystère Picasso, where we can actually watch him on the job, with images materializing on the screen. But even when the artist plays himself, the creative act remains a mystery. As Françoise points out, Picasso had to match the speed of his drawing to the speed of the movie camera. The result is a series of works of relatively little consequence. Perhaps only Warhol knew how to harness art to time.

In any film about a great artist the integrity of his work is at stake. In Picasso’s case the revolutionary nature of the art and the paradoxical nature of the man call for very special skills: understanding of the workings of Modernism and insights into the dark side—the duende—of Picasso’s profoundly ambivalent, profoundly Spanish character. Maybe we should not expect these skills of James Ivory. Commercial entertainment is what he is best at. The trouble is, Surviving Picasso not only fails to entertain; it puts the artist and his work at considerable risk by playing into the hands of modern-art-haters, in this respect like the book on which it claims to be based.

This Issue

October 31, 1996

-

*

“He Says, He Says,” Quest, September 1996, pp. 60-63. ↩