How does a girl become a boy? In his recent film version of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, Trevor Nunn shows us the shipwrecked Viola transforming herself into Cesario in order to be employed by Orsino. Her long hair is cut into a pageboy’s bob; she binds her breasts tightly against her body; she dons trousers, not forgetting to stuff a handkerchief down the front to hint at a penis; she sticks on a false mustache. Then she learns how to move like a man, imitating the sea captain who is helping her: walking with her legs swinging from the hips, finally yawning in an extravagant manner with her arms thrown wide and her mouth open wider. The visible and concealed body, costume, and movement: these are, for Nunn and Imogen Stubbs (Viola), the three features that provide the code for gender. When Viola is reunited with her brother, it is, for Nunn, the mustache that becomes the means of redefining Viola as a woman. Apparently nothing that Shakespeare gives Viola to say is half as convincing as peeling away the false mustache from her upper lip.

But Shakespeare’s Viola did not transform herself into a boy. Her instruction to the captain is disconcerting but explicit: “Thou shalt present me as an eunuch to him.” Here, as occasionally elsewhere in the film, Nunn has adjusted the text: his Viola says “boy,” not “eunuch,” and the troubling hint of castration—a hint that the play does not follow up and that would, in the Victorian atmosphere of Nunn’s film, make even less sense than it normally does—is itself neatly excised.

In Impersonations, his exhilarating study of the performance of gender in Shakespeare’s England, Stephen Orgel has much to say about Viola’s strange use of the word “eunuch,” a word which has not much troubled the play’s editors. He pursues the implications of Viola’s choice of the name Cesario: not only its clear implication of someone “belonging to Caesar” but also the etymological suggestions of “cut” in the name Caesar itself (from the verb caedo by way of Caesar’s Caesarian birth). The name implies, deep within itself, the surgery performed on the boy to turn him into a singer, the specific skill Viola possesses which will make her employable (“for I can sing,/And speak to him in many sorts of music/That will allow me very worth his service”). Where some editors have wondered why it should be that Viola actually does not sing, and have asked whether the original text was revised, Orgel is concerned with a broader problem:

The question, then, is not how this moment functions dramatically, since in any practical sense it does not function at all, but, precisely because of its discreteness and uniqueness, what cultural implications it has.

Viola seems to be proposing not only a gender transformation but also a neutering, “a sexlessness that is an aspect of her mourning, that will effectively remove her…from the world of love and wooing.”

But, as Orgel recognizes, the surgery did not remove desire, only the possibility of sexual performance, leaving the eunuch in a world of imagined but unperformable sexual activity, as Mardian, a eunuch in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, reminds us: “Yet have I fierce affections, and think/ What Venus did with Mars.” In his search for the “cultural implications” of Viola’s choice of disguise, Orgel turns to the castrati of the Vatican, the most famous example of eunuchs in Shakespeare’s time, and finds them used, like the boys of Shakespeare’s acting company, to play women’s roles in performances, so that the choirboys “enabled the introduction of overt sexuality, simultaneously heterosexual and homosexual, into the world of ecclesiastical celibacy.”

Cautiously and convincingly, Orgel’s argument reaches a point where he can suggest that when Viola identifies herself as a eunuch she “both closes down options for herself and implies a world of possibilities for others.” These possibilities include a form of sexual ambiguity and doubleness, what Orgel calls “sexual alternatives and equivalents of either-and-both,” so that, as Viola says to Orsino, “I am all the daughters of my father’s house,/ And all the brothers too,” and, as Sebastian tells Olivia, “You are betrothed both to a maid and man.” From here, Orgel will move on to the “master-mistress” of The Sonnets and to Rosalind in As You Like It.

Orgel’s treatment of Twelfth Night’s momentary reference to Viola as a eunuch exemplifies his method, which is to make us look freshly at a word we have often read or heard but have usually ignored, enabling us to see it as a crystallization of the way a culture considers gender. Here, as so often in his brilliant short book, Orgel’s wide-ranging exploration of Renaissance culture is linked to current studies that interpret gender as something both internal and external. Most such analyses concentrate on the differences between the way people identify themselves as male or female and the ways others perceive them and understand their gender by their gestures, clothes, or mode of speech, as well as the nature of their genitalia. Orgel brings to the subject the discriminating eye of a fine literary critic, testing his evidence with acute sensitivity.

Advertisement

Viola, he writes, chooses to create a gap between her sense of herself as a woman and others’ sense of her as a boy, Cesario. She makes an explicit decision, which the play delightedly tests when it shows the perception of others to her. Viola is allowed by Shakespeare an exhilarating sense of self, which she can set against the way others see her and objectify her, making assumptions about her that must often prove untrue. But at the end of the play the dilemma raised by Viola’s choice is still present for her: Is Orsino in love with Viola or with Cesario, with the woman or the boy? Impersonations argues that in order properly to understand what it means for Viola to disguise herself as a boy or a eunuch, we need to learn much more about the entire way English Renaissance culture understood what it meant to be a boy, or a man, or a woman.

In his densely scholarly study Shakespeare and the Jews, James Shapiro is also concerned with castration. In The Merchant of Venice, when the bond between Shylock and Antonio is formulated early in the play, Shylock proposes that the forfeit for defaulting should be “an equal pound/ Of your fair flesh to be cut off and taken/ In what part of your body pleaseth me.” It is not until the trial scene in Act Four that the play firmly identifies where that part of Antonio’s “fair flesh” is actually placed: “Nearest the merchant’s heart.” Because of our familiarity with the play—we know the story long before we even read or see it—we tend to read it backward, as if the location of the pound of flesh is always explicit. But for a Renaissance audience, there could have been no such assumption, as they watched the long expanse of the play between the bond and the trial scene. Shapiro convincingly argues that, until the trial scene makes all clear, they might have expected the pound of flesh to have been found in a different part of Antonio’s anatomy.

As Shapiro notes, the Geneva Bible (1560), in Leviticus, uses the word “flesh” consistently for “penis.” Shakespeare had used “flesh” in the same way in Romeo and Juliet. Even more explicitly, Alexander Silvayn’s The Orator, translated in 1596, shortly before Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice, and a probable source for the play, has a Jew who announces to the judge, as he demands the execution of his bond,

What a matter were it then if I should cut of his privy members, supposing that the same would altogether weigh a just pound?

Until the trial scene, Shakespeare’s audience was quite likely to have wondered whether Shylock had in mind a form of extremely radical circumcision. Shapiro subtly relates this to Saint Paul’s redefinition of religious identity, a passage crucial to Christian understanding of the meaning of religious identity and one which greatly troubled Reformation theologians:

He is not a Jew which is one outward, neither is that circumcision, which is outward in the flesh. But he is a Jew which is one within, and the circumcision is of the heart.

(Romans 2:28-29)

Saint Paul moves the true significance of circumcision from a visible sign to an invisible one, from the penis to the heart, from outside to inside. Shylock’s knife is, in the trial scene, aiming to make this space of inward circumcision, the area “nearest the merchant’s heart,” gorily visible.

Yet the two explorations of the possible implications of castration epitomize the difference between the two books under review. Orgel writes with unfailing clarity and authority, laying bare the steps of his own thinking step by step, encouraging us to entertain objections to his argument, each of which he carefully answers, while never losing sight of the central theme of his book. Shapiro is so fascinated by the range of material he has found that his argument about the implied castration of Antonio includes a digression on Elizabethan travelers’ accounts of witnessing circumcisions abroad and a long disquisition on the use made by Shakespeare’s editors of a story of a Christian’s attempt to castrate a Jew in Gregorio Leti’s Life of Pope Sixtus the Fifth. His account of Silvayn’s The Orator contains the delightful revelation that Furness, the great nineteenth-century Shakespeare editor, bowdlerized his quotations from it in his edition of The Merchant of Venice, so that the threat to the Christian’s “privy members” became, comically, a threat to his “head.”

Advertisement

Where Orgel wears his immense learning with enviable lightness and Impersonations becomes an authoritative summation of the vast recent research in the tumultuous field of Renaissance gender studies, Shapiro has an enthusiasm that leads him into rich and entertaining side paths. As a result, Shakespeare and the Jews is a repository of information about a great many matters long in need of the kind of intelligent analysis that Shapiro gives them.

Both books take as their central subject the deep cultural anxiety in the Renaissance over the nature and permeability of boundaries. When Shapiro explores Renaissance beliefs about Jews, many only remotely connected with Shakespeare, he describes, in a passage which is peculiarly unnerving for the way we now perceive gender difference, the then-widely held bizarre notion that Jewish men menstruated. Thomas Calvert, writing in 1648, reported the claim that “Jews, men as well as females, are punished curso menstruo sanguinis, with a very frequent blood flux.” The blood-libel, the belief that Jews had to murder Christian children to provide themselves with the blood needed to make matzos for Passover, is bound up with this transgression of gender boundaries: Jewish men murder to collect blood to replace the blood they have lost through the perversion of their masculinity.

Only slightly less extreme was the report that Jewish men were occasionally capable of breast-feeding. At such moments Jews become the epitome of deviance and their murderous deviousness a consequence of their need to cover up this deviance. The bodies of Jewish men, through their allegedly alien physiology, were held to have transgressed the boundaries of gender that were reassuringly fixed in Christian bodies.

How this group was perceived in Renaissance culture is vividly manifest in the doubts felt over conversion. If a Jew converts to Christianity, how can Christians be sure that the barrier has been effectively and permanently crossed, that the conversion is more than superficial? When the conversion was undertaken out of fear or under compulsion, there must always have been the risk that the converts were, as William Prynne worried in 1656, “still playing the Jews in private upon every occasion, and renouncing their baptism and Christianity at last, either before or at their deaths.” After seeing Jews in Avignon in 1596 who were “compelled under severe penalty to attend” conversion sermons, Thomas Platter wrote, “Has it ever been known, in the memory of man, that a Jew hath been converted?”

Conversion is an external manifestation of what ought to be an internal condition. But because the outward signs are clearly visible, any false Christian can go through the forms of conversion as if performing the truth. A false Christian can act convincingly like a true one; there is no available process for verification. Hence any writer referring to converts has a problem of definition: Is a Jew who has converted still to be defined as a Jew? Since there was no agreement whether Jews were members of a race or of a religion, the term “Christian Jew,” as, for example, in John Foxe’s story of “a Christian Jew in Constantinople martyred by the Turks” in his Actes and Monuments (1570), could either be a comment on a mixture of religious belief and racial identity or a disturbingly oxymoronic label for a person whose true faith was indefinable and unknowable.

The three most common terms to describe those who had apparently converted were New Christians, Conversos, and Marranos. Shapiro attempts to distinguish between the three:

I have generally retained New Christian to describe those whose conversion was probably sincere, Converso where the question of apostasy is an open one, and Marrano in cases where Jewish identity is predominant, though disguised.

But this attempt at definition contains the seeds of its own refutation: words like “probably” and “predominant” beg more questions than they can possibly answer. In any case, contemporary usage was full of confusions. John Florio’s A Worlde of Wordes, an Italian- English dictionary of 1598, defined Marrano as “a Jew, an infidel, a renegado, a nickname for a Spaniard,” leaving the word in a limbo of incompatible categories. After the end of The Merchant of Venice, when Shylock has been forcibly converted, the other Venetians would probably continue to refer to him as “the Jew.”

Not knowing who was really a Jew was only part of the difficulty. Shapiro is at his best in exploring the historical circumstances of the Jews’ expulsion from England by Edward I in 1290, and of their supposed readmission by Cromwell in 1656. In both cases Shapiro revises the conventional belief in the absolute nature of these acts of apparent anti-Semitism and philo-Semitism. Edward I’s action is shown to have resulted not from putative anti-Semitism on his part but from a need to bargain with Parliament to secure its agreement to taxation, the expulsion of the Jews being the price demanded. The debate at Whitehall in December 1655 was not over re-admitting the Jews but to determine what rights should be granted to those who were already in England or might come there later. What is more, the debate ended inconclusively, and there never was a formal agreement to readmit Jews. Not only does Shapiro show that neither event happened in the form in which it is still widely believed to have occurred, but he also shows that Jews were always present in England, and that there was, during this long period of their reputed absence, a small but significant number of Jews living in London.

It is not only that the English worried about whether converts were Christians or Jews; they also worried about the ways in which the boundaries of the nation, the borders of the kingdom, were themselves shown to have been porous. Jews had moved into London without anyone having a clear notion whether they were legally entitled to do so and what their rights were. The 1655 debates made some people fear that there would be a large influx of Jews and that, while there might be an opportunity to convert Jews into Christians, there was also a risk that the result would be that Christians became Jews. As Ralph Josselin, the vicar of an Essex parish, noted in his diary, “The Lord hasten their conversion, and keep us from turning aside from Christ to Moses, of which I am very heartily afraid.”

When any of these resident aliens was convicted of criminal behavior, many people were troubled; it suggested that the idea of a nation united in religion was a myth. In 1594 Roderigo Lopez, a Jewish physician resident in England since 1559, and often now identified as a contemporary prototype for Shylock, was convicted for his part in a Spanish plot to poison the Queen. The verdict was taken to have revealed Lopez as a Jew, not the Christian he professed to be; he was laughed at by spectators when, on his way to execution, he affirmed “that he loved the Queen as well as he loved Jesus Christ.” Since Jews were, by definition, a group representing what was not English, the difficulty of excluding them and the difficulty of recognizing them drew attention to the limitations of the concept of Englishness against which the concept of Jews was counterposed.

In Renaissance pictures, the image of the Jew was never clearly defined. Shapiro has found few images of Jewish women, while it is not until the eighteenth century that images of Jewish men have physical features, like large noses, to identify their race. The single most obvious form of physical difference, the circumcised penis, is unseen. In any case, early modern woodcuts were often re-used with new captions and, as a result, specific images of Christians could be re-used to represent Jews. At most, Jews could be confidently identified in images as racially other only by their clothes. Though Shapiro does not say so, the conventional image of the Jew in flowing robes both orientalizes the Jewish man and feminizes him, suggesting another small way in which Renaissance culture, identifying itself as male and Christian, linked together the groups that were unlike itself, whether those groups were as large in number as women or as small in number as Jews.

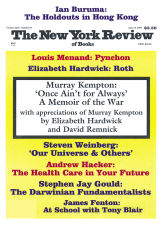

Impersonations begins as an attempt to answer the still-unanswerable question which Orgel used as the working title for his book: Why did the English stage use boys for women? While the peculiarity of the English Renaissance stage in using boys to play female roles is a familiar fact (English women did not act in the professional theater until 1660), it has long been in need of the fresh reconsideration that Orgel provides. The process of exploring possible answers involves him in an extensive investigation of images of men and women, none more remarkable than the one used as the cover illustration for the book. Cornelis van Haarlem’s painting Venus and Adonis (1619) shows the two figures as mirror images of each other. (See illustration on this page.) The only mark of gender differentiation is the swelling of Venus’s breasts and, as Orgel comments, it would appear that “the same model was used for both hero and heroine.” The painting may be little known, but Orgel’s argument shows that it can represent one strong strand of Renaissance thinking about gender. Van Haarlem is not reversing gender in the way that Shakespeare explored in his narrative poem Venus and Adonis, where each of the two figures takes on attributes of the other’s gender. Instead, he shows gender as nothing more than a marginal difference, unimportant even in its erotic significance. Van Haarlem’s painting seems to argue that Venus’s sexual desire for Adonis is not based on her perception of his maleness as different from her femaleness. Her desire is neither heterosexual nor homosexual; gender seems irrelevant to this desire.

In some cases, just as images of Christians could be re-used as images of Jews, images of women could become images of men: the popular iconographer Georg Pictor used the same woodcut for Pallas Athena and for Hercules in his Apotheoseos (1558). In other examples, men could deliberately be represented in female dress without allusion to desire or sexuality. François I was painted wearing a dress—to show that, as the motto explains, the king “en guerre est un Mars furieux/En paix Minerve & diane” (was a Mars in war, Minerva and Diana in peace). If the feminized male is often considered to be emasculated—to be, that is, less than a man—here the doubly gendered image makes the king more than a man, both man and woman, by being all three divinities at the same time.

While Orgel’s search begins with a specific problem in theatrical practice, it takes him into a great many other Renaissance beliefs about gender and sexuality. Renaissance pamphleteers who attacked the stage as immoral often saw the playing of women’s roles by boys as something that would encourage men in the audience to engage in homosexual activity; but it was far more common at the time to fear that the real danger to masculinity was posed by heterosexuality. Desire for women risked turning men into women or, at least, into effeminate men. To be in love with a woman not only distracted a man from male activity such as war, making him less than Mars, but it could also turn him into Venus. It is the worry that Romeo voices when he complains,

O sweet Juliet,

Thy beauty hath made me effeminate,

And in my temper softened valour’s steel!

Homosexuality posed far less of a threat to macho identity than heterosexuality, an inversion of our currently prevailing social beliefs.1

Orgel writes with the great virtue of scholarly skepticism. He re-examines the evidence, for instance, of the conventional account of a specifically English tradition of all-male performance being the result of medieval performances of mystery plays by all-male craft guilds and finds it untrue. Women performed, for example, in Lord Mayor’s Shows in London in 1523 and 1534; there were professional women singers performing in London theatrical performances in 1632. In any case, drawing on recent historical research, Orgel shows that the guilds were not exclusively male preserves: in Chester in 1575 there were five women blacksmiths and in Southampton in the early seventeenth century 48 percent of apprentices were women. Moreover, women performed on the stage in France, Italy, and Spain, countries with their own parallel traditions of guild performances and with even more explicit cultural concerns about maintaining female sexual virtue.

Elizabethan travelers occasionally reported their experiences of seeing foreign actresses, and foreign companies which included women were occasionally seen in London. In 1629 a French company played at the Blackfriars Theatre in London and, though one account recorded that they were “hissed, hooted, and pippin-pelted from the stage,” other accounts suggest that they intrigued audiences and were popular. The fact that these European examples were not consistently rejected with the usual English xenophobia only adds to the difficulties of comprehending the reasons for the English practice of using boy-actresses. Each new piece of evidence that Orgel marshals only makes the sheer oddity of the absence of women from the English Renaissance professional theater all the more striking. As Orgel well knows, he cannot hope to provide anything amounting to a fully convincing explanation of this fact, however suggestive his evidence and arguments may be.

While English Renaissance plays almost obsessively show women either disguised in men’s costume or simulating men’s behavior, they rarely raise the question of women as professional actors. But in one play which Orgel does not investigate, The Travels of the Three English Brothers (1607), a collaboration between John Day, George Wilkins, and William Rowley, the dramatists placed at the center of their play a remarkable debate between two actors. While in Venice Sir Anthony Sherley is visited first by Will Kemp, the famous clown of Shakespeare’s company, and then by an Italian Harlequin and his wife, who are touring and performing commedia dell’arte drama. Sir Anthony proposes that Kemp should give a performance with the Italian troupe. Kemp was famous as a great improvisor, even when he ought to have stuck to the text. It is probably Kemp whom Shakespeare is thinking of when Hamlet orders the actors who are to play at Elsinore: “Let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them.” In The Travels of the Three English Brothers it is proposed that the two great traditions of extemporized comedy, the English clown and the Italian commedia troupe, join together.

Kemp questions Harlequin about his company and is comically shocked to discover that it consists only of Harlequin and his wife:

Kemp. Why, hark you, will your wife do tricks in public?

Harlequin. My wife can play—

Kemp. The honest woman, I make no question; but how if we cast a whore’s part or a courtesan?

Harlequin. Oh, my wife is excellent at that; she’s practised it ever since I married her. ‘Tis her only practice.2

The joke is a simple one but it strikes at the heart of the distrust of theatrical performance, a suspicion that recurs with predictable frequency in anti-theatrical tracts: playing the whore is dangerously the same as being a whore. Here, however, the suspicion is put, remarkably enough, in the mouth of an English actor. There is no suggestion that Kemp himself might become, or play out off stage, the roles that he performs. That actor and role might converge seems a consequence of the presence of a female performer.

Kemp mockingly encourages Harlequin, as the discussion continues, to explore the scenario further: Harlequin will play “a jealous coxcomb,” a role he has played ever since, according to Kemp, “your wife played the courtesan,” while Kemp himself wants to play the man who will cuckold this coxcomb. Kemp cannot wait to start rehearsing and kisses Harlequin’s wife, making her husband furious. But Kemp airily dismisses his complaint: “We are fellows, and amongst friends and fellows, you know, all things are common.” Kemp is both rehearsing and behaving as a fellow player; his action is both a performance and a social greeting to a fellow professional. The boundaries between the playlet they will perform and their social behavior blurs, a confusion that is provoked by the visible presence of the wife as an actor.

Harlequin’s wife stays completely silent in the scene. The female voice is suppressed, and there is nothing in the dialogue of Kemp and Harlequin to suggest that she has any thoughts of her own. By contrast, in the last chapter of Impersonations, Orgel considers three remarkable women, Penelope Rich, Bess of Hardwick, and Mary Frith, each of whom lived their lives in ways that emphasized their own ideas and their resistance to being treated as objects; Orgel writes that each had “a notably successful career that does not fit the standard view of gender roles” in the period. Bess, for instance, rose by brilliantly dealing with financial problems posed by each of her four marriages, the last to the wealthiest man at court, the Earl of Shrewsbury:

In her last years she ran a large financial empire, greatly increased her wealth, built two of the most splendid houses in England, founded a dynasty that still survives, and managed her affairs until her death in 1608 at the age of eighty.

As Orgel recognizes, “it is not clear how far we can generalize” from the case of Bess of Hardwick; but “we should certainly be very wary of dismissing it as an anomalous case.”

Impersonations ends far from where it started, with an examination not of the practice of using boys to represent women but of the ways women could represent themselves in Renaissance society. From exploring the gap between the gender of the performer and the role that performer played, Orgel has moved to demonstrating the ways individual women took control of their lives. In the theater, the conditions of playing meant that women were unable to speak for themselves, since women could not perform as women but could only be characters ventriloquized by the boys who played them; but the three women portrayed by Orgel exemplify the possibility that, as he brilliantly shows, “women might be not objects but subjects, not the other but the self.”

The scene with Kemp in The Travels of the Three English Brothers is framed by two scenes showing the machinations of Zariph, an evil Jew who has Sir Anthony thrown into prison, gleefully announcing “a Christian’s torture is a Jew’s bliss.” Shapiro mentions Zariph, Shakespeare’s Shylock, only in passing as one of the dramatic descendants of Marlowe’s Barabas in The Jew of Malta. Where Kemp can so easily deal with the threat posed by a female actor, it is only with great difficulty that Sir Anthony avoids the threat posed by the Jew. Jews may have been mocked but the belief in their murderous intent was so repeatedly stressed that it surely points to a deep-seated fear. When Zariph claims that “it would my spirits much refresh/To taste a banquet all of Christian flesh,” he may be voicing a cliché but it is a terrifying one, an excuse and a justification for violence toward Jews designed to prevent their violence toward Christians. Zariph, like nearly all Jews in Renaissance writing, is only a mouthpiece for a Christian view of Jews. The Jews’ own voices stay unheard. Where Orgel can end with a celebration of female achievement, Shapiro’s unimpassioned scholarship can only recount another bleak chapter in the history of European anti-Semitism.

This Issue

June 12, 1997