Carried forward amid an ocean of cheering refugees in the Stankovic refugee camp, Madeleine Albright could hardly contain her excitement. “We have been victorious,” the secretary of state shouted triumphantly to the roaring crowds, “and Milosevic has lost!” As she spoke, Slobodan Milosevic issued orders in Belgrade; Russian troops, with his happy connivance, marched into Pristina, embarrassing their supposed NATO allies. And more than eight hundred fifty thousand Kosovar Albanians languished in their tent cities in Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro.

“We have fought this war so the refugees can go home,” Albright told them, showing a more persuasive grasp of theater than of logic: two and a half months before, few of the men, women, and children surrounding her had been refugees. Addressing his countrymen on the eve of the war, President Clinton had announced quite a different goal. “We act,” he told Amer-icans on March 24, “to protect thousands of innocent people in Kosovo from a mounting military offensive…. We act to prevent a wider war, to defuse a powder keg at the heart of Europe, that has exploded twice before in this century with catastrophic results.”

President Clinton’s geography, and his history, were as uncertain as his secretary of state’s logic, but his argument came through with admirable clar-ity: “By acting now, we are upholding our values,” he said. “Ending this tragedy,” he said, “is a moral imperative.”

Fine words on which to launch a war, and it is against them that the Kosovo “victory” must now be judged. How does one prepare a moral balance sheet? Begin with brute facts: before, a small province torn by a low-level guerrilla uprising and a savage counterinsurgency staged to suppress it; tens of thousands of people homeless, perhaps two thousand dead.

And after? A land destroyed; countless houses and schools burned; nearly a million people stripped of their homes, their belongings, their identities, deported and displaced. And finally—critical spaces still blank on the balance sheet—scores, perhaps hundreds, raped; thousands, perhaps many thousands, dead.

Brute facts are not all, of course. That “moral imperative” can be extended, telescoped, as President Clinton recognized on March 24:

All the ingredients for a major war are there. Ancient grievances, struggling democracies and in the center of it all, a dictator in Serbia who has done nothing since the Cold War ended but start new wars and pour gasoline on the flames of ethnic and religious division.

Mr. Milosevic, of course, rules still in Belgrade. As for his policy of sowing “ethnic and religious” division—which, unopposed, had produced a Croatia “cleansed” of Serbs and an ethnically partitioned Bosnia—the West was now forced to confront it:

All around Kosovo, there are other small countries, struggling with their own economic and political challenges, countries that could be overthrown by a large new wave of refugees from Kosovo.

And yet, during the weeks after the President spoke, that “large new wave” of refugees that the war was intended to forestall did indeed break on the shores of Albania and Macedonia, rendering increasingly unstable this “major faultline between Europe, Asia and the Middle East,” and making likely a partitioned, or solely Albanian, Kosovo.

Yes, Milosevic’s calculated savagery produced the refugees; the blame must be laid at his feet. Not entirely, though: at Rambouillet American and Western diplomats practiced a statecraft that was ill-prepared, fumbling, and erratic, and no one can say what Kosovo might look like—and how many Kosovar Albanians might still be alive—had Secretary Albright not handed to the Serbs an arrogant ultimatum whose consequences she and her fellow diplomats confidently predicted (a quick capitulation, or at the very least a rapid Milosevic retreat), and which they got precisely and historically wrong.

“We learned some of the same lessons in Bosnia just a few years ago,” Mr. Clinton advised Americans as the bombs began to fall. “The world did not act early enough to stop that war either.”

And let’s not forget what happened. Innocent people herded into concentration camps, children gunned down by snipers on their way to school, soccer fields and parks turned into cemeteries. A quarter of a million people killed….

At the time, many people believed nothing could be done to end the bloodshed in Bosnia. They said, “Well, that’s just the way those people in the Balkans are.”

Who were these “many people” who “believed nothing could be done”? President Clinton’s first secretary of state, Warren Christopher, perhaps, who in May 1993 called to mind Neville Chamberlin in describing Bosnia as “a humanitarian crisis a long way from home, in the middle of another continent”? Or President Clinton himself, who, in explaining why “the United States is doing all we can to try to deal with that problem,” had noted that in Bosnia “the hatred between all three groups is almost unbelievable…. It’s almost terrifying…. That really is a problem from hell….”

Advertisement

In the Clinton White House nothing is more ephemeral than history. In Bosnia, as the President now recalled it, “We and our allies joined with courageous Bosnians to stand up to the aggressors” and thereby learned that “in the Balkans, inaction in the face of brutality simply invites brutality. But firmness can stop armies and save lives.”

In Bosnia, of course, such “firmness,” in the form of aerial bombardment, came from a paralyzed America only after three years of genocidal war and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. In Kosovo, the firmness came in the same form; but it did not “stop armies,” at least not for seventy-nine days, and it is a difficult argument to make that it saved lives—or at least that it saved Kosovar lives.

American lives of course it did save. Amid the carnage of Kosovo, and the more than 1,200 civilian deaths in Serbia, not a single American airman or soldier, indeed not a single member of the Western alliance, died; not one suffered injuries. And here we reach the bleak underside of President Clinton’s “moral imperative” as it was played out during those seventy-nine days. For Kosovo represents the grail which American leaders have been seeking for decades: the politically cost-free war.

Call it the Athenian Problem: How can a democracy behave as a world power? How might its citizens—used to rousing themselves to an interest in world affairs only during wartime, and lethargically even then—be persuaded to send its sons to fight in battles far away, in places apparently unrelated to the country’s defense? American leaders have found the political costs of such persuasion to be high and have shown over the decades a growing eagerness to avoid them—by, for example, masking the country’s foreign policy with covert action, as Eisenhower did by overturning governments in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954; or by refusing to order full mobilization and otherwise minimizing the cost and extent of war, as Johnson did in Vietnam.

Technology, America’s most cherished faith, has carried the country a long way since then, making the immaculate war possible; but the sentiments behind that goal, the reluctance of American leaders to risk their political capital to persuade the people of a war’s necessity, have grown ever more vehement. “Americans are basically isolationist,” Clinton told George Stephanopoulos in 1993, as a firefight raged in Mogadishu. “Right now the average American doesn’t see our interest threatened to the point where we should sacrifice one American life.”

President Clinton would do nothing to convince that “average American” otherwise, and when eighteen bodybags arrived from Somalia he hastened to arrange for US troops’ departure. When the following year he was forced to send American troops into Haiti he did it in a way certain to avoid casualties—few Haitian paramilitaries were disarmed or other risks taken—and the invading force suffered no casualties (while Haiti today remains arguably worse off than before).

It was in Kosovo that the moral calculus behind this evolution became unmistakable. During his triumphant press conference of June 10, 1999, Secretary of Defense Cohen described marvels of technology—the fact that “of more than 23,000 bombs and missiles used, we have confirmed just twenty incidents of weapons going astray from their targets to cause collateral damage.” But during that very long “briefing,” which runs to nearly thirty printed pages, the secretary of defense and his generals said nothing of the Kosovars and what had happened to them. Rather: “We were able to operate,” said General Shelton, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, “without losses in a very robust air defense system….”

Without losses: a war without losses. And indeed why should one complain about Americans surviving—about a flawless war? But of course it wasn’t flawless. Perhaps one day there will be a method to calculate how many Kosovars had to be displaced, how many had to die, for the West to prosecute its “perfect” war. How many fewer might have died if the “campaign” had targeted—or had plausibly threatened to target—the men with guns who were killing and expelling the people America’s President had sworn to protect? Such a war would have held risks for Americans; their countrymen would not have liked this. Leaders who speak of “moral imperatives,” however, should be held responsible for their words and for persuading their people that some causes, once embraced, are worth the risk.

—June 17, 1999

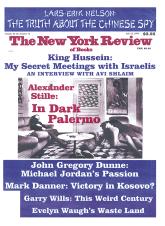

This Issue

July 15, 1999