1.

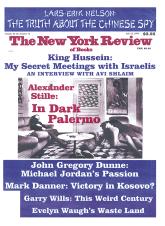

One morning in 1993, several Italian policemen arrived unexpectedly at the house of Letizia Battaglia, where she has her office, carrying a warrant to conduct a search of her vast photo archive. Battaglia had worked as the photography director of L’Ora, Palermo’s left-wing daily newspaper, from 1974 until shortly before the paper folded in 1990. She had begun to document the atrocities of the Mafia long before it was popular or safe to do so. Either Battaglia or one of her assistants was present at the scene of nearly every major crime as Palermo descended into one of the most bloody and tragic periods any European city has known since World War II.

Between 1978 and 1992, Cosa Nostra murdered virtually every public official in Sicily who interfered with its business: the chief of detectives, the head of the fugitives squad, and the deputy chief of the Palermo police; the general in charge of the military police; three chief prosecutors; the head of the leading opposition political party in Sicily; the head of the leading government party; two former mayors of Palermo; the country’s two most important Mafia prosecutors; and even the president of the Sicilian Region, the highest-ranking elected official on the island.

Along with political assassinations, a newly dominant group within the Sicilian Mafia from the nearby town of Corleone undertook a major Mafia war, a veritable campaign of extermination intended to eliminate their rivals within the organization, as well as anyone (whether friends or relatives) who could offer support to their internal enemies. The result was that some one thousand people were either murdered or made to disappear.

On call from morning until late at night, Battaglia sometimes found herself at the scene of four or five different murders in a single day. In the course of this grisly routine, she and her longtime partner Franco Zechin produced many of the images that have come to represent Sicily and the Mafia throughout the world: a corpse lying face down in an alleyway; a boy with his face hidden in a nylon stocking, brandishing a weapon—the gun is a toy, but the look on the child’s face is that of a hardened killer; a group of black-shawled women sitting impassively on chairs in the presence of a corpse bleeding onto the sidewalk.

But it was not the scene of a murder that the Palermo police were looking for that day in 1993. In her sixteen years at L’Ora, Battaglia photographed virtually everything of possible interest to the newspaper—fashion shows, crime scenes, religious processions, striptease performances, political rallies, and glittering receptions in the palaces of Palermo’s aristocracy. Taking hundreds of pictures a day for nearly twenty years, Battaglia accumulated some 600,000 images—most of which remain in negatives and contact sheets—creating an extraordinary visual chronicle of Sicily over the nearly twenty years of a period of convulsive change.

Battaglia’s archive is organized by subject. The police asked to see the file on the Christian Democratic Party—the party that had governed Italy for the entire post-World War II period. Sicily had been a political stronghold for the Christian Democrats since the end of World War II. With the Italian left seemingly on the brink of power after the war, the new Italian parties made use of the Mafia in opposing the Communist Party, and organized crime did much to intimidate any radical forces on the island. Between 1945 and 1955, forty-three Socialists and Communists were murdered in Sicily, generally around election time. Unfortunately, the governing parties became more, not less, dependent on the Ma-fia as the tensions of the cold war began to ease. By the 1970s, the Christian Democrats’ support had dropped below 30 percent in most of Northern Italy, while they routinely were supported by more than 45 percent in places like Palermo.

In those conditions, the Christian Democrats were not willing to get rid of local political bosses who had connections with organized crime and could also deliver the vote. Battaglia took a series of photographs of Vito Ciancimino, the former Christian Democratic mayor of Palermo and former barber of Corleone—rumored for many years to be in the pocket of Salvatore (Totó) Riina, the boss of bosses of the Sicilian Mafia. Battaglia took rather chilling photographs of Ciancimino laughing jovially as an honored guest at various Christian Democratic Party gatherings, at a time when he was supposed to have been persona non grata. Among them are photographs of Ciancimino with Salvatore Lima, another former mayor of Palermo and Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti’s chief political supporter in Sicily.

With the end of the cold war the lid appeared to come off the system. In early 1992, prosecutors in Milan began an extensive investigation into political corruption that quickly spread to all parts of the country. That summer, Italy’s leading anti-Mafia prosecutors, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, were blown up by car bombs in Palermo, provoking street protests throughout Sicily. After that, evidence began to emerge of widespread collusion between organized crime figures in Southern Italy and politicians at all levels of government. In early 1993, prosecutors in Palermo indicted Giulio Andreotti himself—seven times prime minister and until recently the most powerful politician in the country—for alleged ties to the Sicilian Mafia.

Advertisement

The police who arrived on Battaglia’s doorstep were looking for evidence in the Andreotti case. What they found was a photograph from the late 1970s showing Andreotti with a Sicilian businessman named Nino Salvo, who was later found to have been one of the linchpins of the Mafia system in Sicily. Salvo had been one of the biggest financial supporters of the Christian Democratic Party in Sicily as well as, according to the phrase, a “made” Mafia member who acted as the principal go-between for Cosa Nostra’s dealings with its friends in government.

Andreotti always insisted that he had never met Salvo. But two photographs in Battaglia’s archive showed them together on the occasion of a Christian Democratic rally in Sicily. Salvo, in fact, was the host of a big reception after the rally at the luxurious Zagarella Hotel outside Palermo, which he owns, and in one photograph Salvo is seen greeting Andreotti. Andreotti insists that even if he met Salvo, he does not recall having done so. Battaglia herself forgot she had taken the picture. Its potential significance was only apparent fifteen years after it was taken. Other than the testimony of Mafia turncoats, the photographs are the only piece of hard, physical evidence directly linking Andreotti to a known Mafia member, and it was a serious blow to the former prime minister’s credibility. (A verdict in his trial is expected later this year.)

The Andreotti photograph illustrates dramatically the historic value of Battaglia’s work. During the 1970s and most of the 1980s the killings in Palermo and the power of the Mafia in general were dismissed by many Italians as a marginal and local problem. After all, many people shrugged, they’re just Sicilian gangsters killing one another. Only in the last few years have people in Italy begun to understand that much more was at stake in the Mafia wars of Palermo than which rival faction would rule the roost.

2.

Battaglia lives in the old historic district of Palermo—a desperately poor and largely abandoned neighborhood in which one sees the best and worst of one of the most fascinating and beautiful cities in Europe. This quarter was once the center of the Palermo aristocracy; and its grand seventeenth- and eighteenth-century churches and palaces—filled with elaborate gilded stucco work and frescoed ceilings—are among the great expressions of baroque architecture. When I was in Palermo last summer the magnificent fountain-statues at the Quattro Canti, the crossroads at the center of the old city, seemed to have acquired yet another layer of grime. The baroque palace opposite the city hall is abandoned, its upper-story windows broken. Just a few blocks from the city hall, toward Battaglia’s house along Via Macqueda, there is still an empty lot that has been in ruins since being bombed in World War II. Above the rubble, you can still see the bust of a female figure in gesso on the empty façade of a building that now no longer exists.

Turning off the wide boulevard of Via Macqueda into the tiny alleyways that lead toward Battaglia’s house, one enters a world that seems little changed since the eighteenth century. Down one alley, there is a puppet theater for children. Down another, old women sit on their balconies and fan themselves against the oppressive heat. On the chipped and faded walls of several buildings there are little glassed-in altars with pictures of the Madonna illuminated by a dim electric candle. A dense honeycomb of wooden scaffolding and wooden poles extends across many of the alleys from one building to another, as if it was holding the buildings up. Palermo is a city that has for decades had a department of edilizia pericolante, “collapsing housing.” In fact, Battaglia moved to her present address after the ceiling of her former apartment fell in.

Battaglia lives and works in a small, three-story house with her office and darkroom on the ground floor. Her kitchen and living room are on the top floor, and issue out onto a terrace with umbrellas and leafy pergolas. Although she is now sixty-three, Battaglia appears to be much younger. She is a small woman with shoulder-length blond hair and a pretty, delicately featured face. Her hair is a little disheveled, held in place by her glasses. In her loose clothes and sandals she looks as if she is too busy to be bothered with her appearance.

Advertisement

Battaglia is a veteran of the radical movements of the 1960s, which, in Italy, came late but then lasted throughout the 1970s and, in her own case, remain a strong influence. She has fought innumerable political battles in Palermo, demonstrating against the Mafia, against American cruise missiles on Sicilian soil, against countless ugly development projects—and in favor of the environment, feminism, and better treatment both for the mentally ill and for the North African immigrants who in recent years have been landing at Palermo. She threw herself directly into politics in 1985, winning a seat on the Palermo city council as a representative of the tiny Green Party. She has also served as a member of the Sicilian parliament and as the city administrator of “urban livability,” a department created by and for her. And although she retired from the city council in 1997, she now wants to set up a service to help prisoners in the Palermo jails, working with the same “mafiosi” she fought to have placed behind bars. “Even the rights of the mafiosi must be respected,” she says. “We can’t have a society with thousands and thousands of people in prison. We have to reintegrate them.”

Like most things in Battaglia’s life, moving to this neighborhood in 1990 was a political act, for she has bet her money and her personal security on the revival of Palermo’s degraded historic core. Initially, it looked to be a losing gamble. Her house was broken into and robbed three times within the first couple of years she lived there. After the third time, she was so angry that she went out into the street and began screaming at her neighbors. Knowing that little escapes them, she blamed them for complicity in the robberies. “What kind of people are you? You have eyes, how can you sit there and let this happen!” she shouted. “After that,” she said, “it never happened again.” A young North African boy, however, to whom she had given a room in her house, had his motorbike stolen. An old woman from the neighborhood came to Battaglia and said, “Signora, don’t scream, we’ll help you.” Within a couple of hours, the motorbike was returned—no questions asked, no explanations given.

3.

The abandonment of the historic Palermo district is an important part of what has been called “The Sack of Palermo.” The city’s administrators gave the green light to real estate developers—most of them connected to the Mafia—to put up numerous high-rise apartment houses in the newer part of the city between the center and the airport. This building orgy, which produced a horribly crowded and ugly modern city, was accompanied by a policy of neglect of the old center. Because the historic buildings could not legally be torn down, they didn’t interest developers: throwing up cheap high-rise apartments was much more lucrative than patiently restoring seventeenth- and eighteenth-century structures.

Moreover by failing to repair buildings, many owners and developers hoped they would soon be able to tear them down and rebuild from scratch. Many districts were left for months or years without gas, electricity, or hot water, forcing residents to move out into the new housing projects. Between 1951 and 1981, the population of the center of Palermo dropped from 125,481 to 38,960—a period in which the city’s population nearly doubled. Those who remained behind were generally the city’s poorest and most wretched, prepared to put up with third-world conditions, like those of the poorer sections of Mexico City or Istanbul.

Palermo’s ruins are the legacy of Salvatore Lima and Vito Ciancimino. Between 1959 and 1964, when they were respectively mayor and commissioner of public works, the city issued 4,000 building permits, 2,500 of which went to three obscure local men whom the Italian parliament’s anti-Mafia commission has described as “retired persons, of modest means, none with any experience in the building trade, and who, evidently, simply lent their names to the real builders.”

Battaglia herself grew up on the other side of Palermo, in a middle-class family that lived in an anonymous-looking high-rise. Her father worked on a cruise ship as what she calls a “maître d’hôtel.” Because of her father’s work, she lived as a young girl in various Italian cities, including Trieste and Naples, and found life in Palermo closed and restricted when she returned at the age of ten at the end of World War II. “I was no longer free,” she said. “A girl, in Palermo, was not allowed to go out by herself.” She married at the age of sixteen and had three children in rapid succession. But she became restless and dissatisfied and caught up in the ferment of the late 1960s. “My husband and I didn’t get along: I wanted to do things, and my husband didn’t want me to do things,” she said.

In 1969, she began to write for L’Ora, the left-wing daily newspaper in Palermo, the alternative to the Giornale di Sicilia, which was closely tied to the Sicilian establishment. The next year, one of her colleagues at the paper, Mauro de Mauro, was kidnapped and killed by the Mafia. “One day, he just never showed up at work,” she said. “At first we joked about it: ‘He must have gotten drunk, look under his table.’ But we never saw him again. Nobody knows just what happened. If we knew, perhaps we could have avoided some of the troubles to come.”

In 1971, Battaglia left her husband and continued to write for L’Ora in Milan, and, to supplement her income, she began taking the photographs for her stories. Editors interfered much more with stories that had to fit the political and editorial line of the paper, but photography was considered a technical skill about which editors had much less to say. So when L’Ora asked her to return to Palermo as director of photography, she accepted.

In 1974, when Battaglia returned to Palermo, the Mafia was no longer a political issue. For several years, after the end of a vicious Mafia war in the mid-1960s, there had, in fact, been a dramatic drop in criminal violence. In response to a large-scale police crack-down, many bosses had fled the country or were lying low, waiting for the trouble to pass. Many Sicilians speculated that the Mafia was dead. Occasional signs of Mafia violence, such as the disappearance of Mauro de Mauro, were brushed off as another of the mysteries of Palermo.

In fact, in 1974, the Mafia was starting to come back stronger than ever. The previous year, a series of major mafia trials which had been initiated during the 1960s ended in acquittal. The bosses of the major Sicilian families decided to re-form the Commission, the committee that acted as the “government” of the Mafia. At the same time, they decided to go heavily into the business of international heroin trafficking. Until then, much of the heroin entering the United States was being exported by Corsican gangsters in Marseilles. But the “French Connection” had been severely disrupted by arrests, and the Sicilians saw an opportunity for a new source of profits. Indeed, the life of the organization and, with it, that of Italy was about to change dramatically. In 1974, a mere eight people throughout Italy died of heroin overdoses—within a little more than a decade, the number of dead would climb to more than one thousand a year. And Italy’s population of hard-core addicts would reach more than 200,000.

Few Sicilians protested against the Mafia. One who did was Giuseppe Impastato, the son of a mafioso from a small town near Palermo, who had the temerity to publicly denounce the new head of the Commission, Gaetano Badalamenti, and was killed during the spring of 1978. Soon after, Battaglia photographed the body of Giuseppe Di Cristina, a powerful Mafia boss from the other side of Sicily. Although this was not widely known at the time, Di Cristina had taken the highly unusual step of warning the police that a new and particularly ruthless group of mafiosi, from Corleone, was taking over. The old mafiosi, Di Cristina said, had a policy of trying to minimize violence and to limit attacks on government officials—but the Corleonesi would stop at nothing.

Although they went unheeded, Di Cristina’s predictions came true. As a few lone, courageous police officers began to try to combat the growing heroin trade, the Corleonesi began to kill anyone who got in the way. One of their most effective opponents was Boris Giuliano, head of the Palermo police department’s squadra mobile, who was gunned down as he was drinking his morning coffee in a Palermo cafe on July 21, 1979.

“Giuliano was a truly extraordinary person,” Battaglia said. “Before him, we tended to hate the police. They were the people who beat up demonstrators. Giuliano was the first who gave the feeling of working for us, to liberate us from the Mafia.” Battaglia has only photographs of Giuliano alive. For when she arrived at the scene of the killing, the police did not want to give the Mafia the satisfaction of seeing the corpse of one of their most courageous enemies, and she was not allowed to photograph the body.

Just two months later came the murder of Cesare Terranova, an outspoken foe of the Mafia who was returning to Palermo to take over the investigative office of the city’s prosecutor. Not long afterward, Battaglia went for a drive on a Sunday morning and came upon several Palermo policemen who were pulling the limp and bloody corpse of Piersanti Mattarella, the president of the Sicilian Region, from the car in which he had been murdered. Because Mattarella had blocked a series of public contracts awarded to companies that were suspected of being Mafia-controlled, he represented the hope of a new, reformed Christian Democratic Party in Sicily. “With the death of Mattarella, we thought we had hit bottom, but it was just the beginning,” Battaglia said. The chief prosecutor of the city, Gaetano Costa, was then gunned down in broad daylight in downtown Palermo after having dared to arrest members of one of the leading Mafia families as part of a growing drug-trafficking investigation.

The next year, instead of the selective killing of public officials, hundreds of mafiosi were killed in a wholesale massacre. Suddenly, the bosses of the principal Mafia families in Palermo—along with their closest lieutenants and soldiers—were being murdered one after the other. It appeared to be an internal Mafia “war,” and the Palermo press speculated that drug policy was the cause of the conflict between the old traditional families. In fact, there was no such war. All of the families were together in the drug trade, but one faction—the Corleonesi and their allies—simply wanted all the power and money for themselves. Dismissed as viddani (peasants), Totó Riina and his Corleonesi associates took their revenge against the big city bosses, avoiding reprisal by getting other key members of the rival families to help with the killing. Having decapitated a family, they then hunted down those suspected of being loyal to the old boss and any friends and relatives who might hide or help the fugitives. By 1981, there was a killing every three days and sometimes several in one day.

“For years, I photographed dead bodies,” Battaglia said. “But I never photographed the assassins. We never knew. If it was a normal murder, they discovered the killer immediately, but in Mafia cases, never…. We felt humiliated, a people crushed and humiliated by this Mafia tragedy,” she said.

Battaglia’s presence at the scene of these crimes was often a subject of controversy. “A woman photographer in Palermo at that time was not particularly accepted,” she said. “I always had problems with the police, with the family of the victims.” At a certain point, she began receiving anonymous letters with death threats. She took them to Giovanni Falcone, the top Mafia prosecutor in Palermo during the 1980s, who advised her to stop working for a few months. She decided to continue and nothing happened.

It was not always easy to tell what sort of photograph might hit a delicate nerve. One day, Battaglia was photographing a striptease show when the proprietors became extremely angry and threatening. When she refused to give them the roll of film, arguing that it contained frames from a previous shoot, they drove her back to her studio. “They took me into the darkroom and forced me to develop the film and cut out the few miserable shots that I had taken,” she said. “I called the police, but they decided to do nothing.” Battaglia still does not know what she had seen that day that she was not supposed to see. “For years every morning when I stepped outside, I was afraid,” she said.

Not long after, she incurred the wrath of Leoluca Bagarella—the brother-in-law of Totó Riina himself and one of the bloodiest killers in all of Cosa Nostra. When Battaglia began to photograph him after his arrest in the early 1980s, Bagarella tried to break free and attack her. Battaglia took a famous photograph of Bagarella that captured all his rage and ferocity. In retrospect, Battaglia regrets that and similar pictures. “I was also ashamed of photographing people when they were arrested, but the newspaper insisted. The moment in which someone, even a mafioso, loses his liberty is a terrible thing, a moment of total defenselessness, and one should respect that, I think.”

Battaglia’s pictures from the streets of Palermo are an important complement to her Mafia reportage. Her many photographs of religious occasions—of a woman crawling up the stairs of the church on her knees, for example—convey something of the tragic tone of life in Sicily. The Sicilians have lived under oppressive rulers from the Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, and Spanish to the Mafia. The fervent belief in the hereafter among many Sicilians today, the intensity of their religious passion, express the hopes for redemption from a world of almost uninterrupted hardship and suffering. Death has always pervaded Sicilian culture and il Giorno dei Morti (the Day of the Dead) in December is as important in Sicily as Christmas in other parts of Europe. One of Battaglia’s most striking photographs is of a murder victim with a picture of Christ wearing a crown of thorns tattooed upon his back.

Millions of Sicilians live outside the law—selling contraband cigarettes, counterfeit tapes, or watches, operating stores or stalls without a license, or simply underreporting their income and evading taxes. This makes many of them both afraid of the legal authorities and vulnerable to pressure from the Mafia. Battaglia remembers a day in 1984 when eight men were found murdered inside a Palermo stable. The exact reasons for the killings remain obscure, but it almost certainly had something to do with the Mafia’s control of illegal horse racing and the illegal butchering of horses for their meat. When the police arrived, they found the relatives of some of the victims trying to take away their bodies: they were removing evidence of the crime instead of alerting the police.

Equally revealing are Battaglia’s photographs of the Palermo aristocracy. Of special note is the photograph of Palazzo Ganci, the home of the Princes of San Vincenzo, used in the making of Luchino Visconti’s film The Leopard. In the 1980s, the young Prince himself was arrested in a Mafia roundup. Relations between the Sicilian aristocracy and Cosa Nostra go back to the origins of the Mafia in the mid-nineteenth century. Many early mafiosi were administrators of the large feudal estates, who often used violence and intimidation against their rivals when the big properties came to be sold and divided up. In many cases, the nobility made deals with these mafiosi either to protect themselves or to intimidate their enemies or competitors. The Prince of San Vincenzo evidently was an important player in the Mafia, holding meetings of the organization in his various houses. The day he was arrested, there was a big reception at which much of Palermo high society would be present. Despite the arrest, according to Battaglia, the Prince’s mother insisted on going anyway: “‘Nothing’s happened,’ she said. ‘Nothing’s happened.’ Part of our aristocracy and bourgeoisie were often the accomplices of the mafia.”

Gradually, however, the killings of the 1980s and the courageous response of a new generation of Palermo magistrates began to erode the attitudes of indifference, collusion, and omertà. A rebellion began among the Jesuits and within the Christian Democratic Party. Its chief representative was a young city councilman, Leoluca Orlando, who had been a political disciple of Piersanti Mattarella, whom Battaglia had photographed at the scene of his murder in 1980. Battaglia, who joined the city council in 1985, was initially suspicious of Orlando. “I made war on him, because he was a dirty Christian Democrat; then I understood that, in fact, he was a real progressive.”

Battaglia represented the small Green Party and began to attack a major development project that would have destroyed another important part of the Sicilian coast near Palermo. “The project seemed horrible to me,” Battaglia said. “It would have cemented over much of the coast east of Palermo.” She was surprised that a colleague from the Green Party, whose place she was taking on the city council, had supported it. Battaglia then learned that the woman was going to work for the development company. “I was one of only four councilors who opposed the project, which had been approved by the previous administration,” Battaglia said. “And we had to fight for years.”

Orlando seemed initially to favor the project, which his administration had inherited from his predecessor, but he eventually turned against it. It turned out that the leading developer when he was later arrested confessed to having relations with the Mafia as well as to distributing bribes to politicians in order to win approval for the project. In the years of trying to defeat the project, Battaglia observed how the developer, Benedetto D’Agostino, was courted and befriended by the most powerful politicians of the city, joining some of them on yachts equipped with bathroom faucets made of gold. She photographed his wedding, at which the best man was none other than Salvatore Lima.

To Battaglia’s pleased surprise, Orlando waged war against Lima and Ciancimino and their allies in Palermo and formed an “anomalous” government, which allied reform-minded Christian Democrats and Communists in the same city administration. Battaglia became commissioner of “urban livability” and set about trying to have the city’s streets and parks cleaned up. Battaglia and Orlando found themselves trying to reverse decades of neglect, in which the garbage collection system, like so much else in the city, was a means of distributing patronage no-show jobs and siphoning money to Mafia-controlled subcontractors. “They didn’t clean the city,” Battaglia said, “and people in Palermo, seeing that the garbage wasn’t collected, in a spirit of perversity, made it even dirtier. They have never loved government and never believed in the people governing them. They would keep their houses spotless, but dump garbage just outside the door. I made some incredible scenes,” Battaglia said.

One episode that Battaglia recalls with particular fondness occurred when she set about trying to clean a small park in one of the poorest, most Mafia-infested neighborhoods in the city. “The park is near a very old and beautiful bridge, but all these trucks were parked all around so that you could not see either the park or the bridge. I went to the shopkeepers who owned the trucks and asked them if they could park somewhere else. ‘Signora, you want to ruin us,’ they said. ‘I’m just trying to make the neighborhood more attractive.”‘ Battaglia announced that she was going to sit there until the trucks moved. “I sat on the sidewalk all day, my workers tried to get me to leave. Then one of the owners said: ‘Signora, you are going to ruin us, but we will move the trucks.’ They understood that I was not there to get money or votes. They decided to give up a personal advantage for a collective good. It was a sublime moment.”

Orlando’s first government—his unprecedented experiment in combining Christian Democrats and Communists—was known as the “Palermo Spring.” Along with trying to clean up the city, the Orlando administration took a different position toward the Mafia. Other administrations had avoided even pronouncing the word “Mafia” in public. Orlando openly encouraged Mafia investigations and between 1985 and 1987 his administration took its place beside the prosecutors as a “friend of the court” in the so-called “maxi-trial” of Palermo, a case involving more than 400 Mafia defendants, including their top bosses.

Nonetheless, the first Orlando administration, with its tenuous majority in the city council, was able to change only a few of the fundamental aspects of Palermo life. Water, for example, was available only every other day, so that most Palermo families were reduced to filling their bathtubs to store water for the days the taps were dry. Children attended schools in shifts, some in the morning, others in the afternoon, because of a shortage of classrooms. Millions for school construction were given to Mafia-controlled construction companies that would drag out the job in order to run up the cost, often leaving a school unfinished. Orlando, although still a Christian Democrat, attacked his party’s leaders, especially Prime Minister Andreotti and his Sicilian viceroy, Salvatore Lima. Eventually, in 1991, his colleagues in the party succeeded in putting an end to this annoying Palermo experiment, and Orlando was out of office.

However, Lima’s Christian Democratic political machine came crashing down in 1992. In March, on the eve of national elections for parliament, Lima was murdered while preparing a campaign appearance for Andreotti scheduled to take place a few days later in Palermo. In view of the longstanding rumors about Lima’s ties to the Mafia, the killing was a deep mystery. A few months later, various Mafia witnesses testified that Lima was murdered because of a prior decision of the Italian Supreme Court upholding the convictions of the leading bosses of the Mafia in the maxi-trial, probably the most important Mafia case in Italian history. According to more than a dozen former mafiosi, who are now government witnesses, Lima was assassinated because he was ordered to fix the case and failed.

After Lima’s death, the Mafia went on to murder the immensely courageous anti-Mafia prosecutors Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino. The Italian parliament, faced with growing public outrage, began to investigate collusion between the Mafia and prominent politicians. The Palermo Mafia scandal occurred at the same time as the larger investigation of political corruption begun by prosecutors in Milan. Palermo and Milan were the epicenters of the earthquake that toppled the political parties that had governed Italy throughout the postwar period.

The scandal led to the indictment of Prime Minister Andreotti, the dissolution of the Christian Democratic Party in Sicily, and the return to city hall of Leoluca Orlando. The Italian parliament passed a series of political reforms, including a new law that allowed for the direct election of mayors. (Under the old system, people voted for a political party and not an individual candidate, putting the selection of the mayor in the hands of party apparatchiks.) The new system, for the first time, made mayors directly responsible to the voters who gave them the popular mandate needed to govern. Orlando, after winning a solid majority, began to tackle many of the problems that had remained unresolved in his earlier administration. With the assassinations of Falcone and Borsellino, Battaglia gave up her nearly twenty-year career of photojournalism and stopped photographing crime scenes. She started her own small publishing house and threw herself into politics.

4.

Despite the grime and decay, there are signs of a surprising and significant improvement of life in Palermo, changes for which Battaglia is partly responsible. The city is cleaner and safer than it was ten years ago. The Orlando administration has modernized the bus service of the city, to almost universal praise. “There were no bribes as far as we can tell,” a prosecutor said. “They gave the contract to a French company,” he added by way of explanation. The city government has finally eliminated the scandal of double shifts in the schools. “There was an incredibly high dropout rate in Palermo, and many people were unable to read. Now the kids go to school and can create a future for themselves,” Battaglia says.

The Teatro Massimo—the city opera house, just a few blocks from Battaglia’s house—which had been closed for repairs for a quarter of a century, has reopened. For years, the theater, covered in soot and surrounded by construction scaffolding, had been a symbol of the hopeless corruption of Palermo. The project to renovate it never seemed to make any progress; it cost tens of millions of dollars and created hundreds of patronage or no-show jobs, all for the benefit of unscrupulous politicians and Mafia-controlled construction firms. After a series of indictments by the Chief Prosecutors Office in Palermo, the Orlando administration finally had construction crews working around the clock. Palermo now has one of the most handsome theaters in Italy back in working order, its cleaned limestone rotunda and pillars gleaming in the honey-colored Palermo light. “At last we have honest people handling these things,” Battaglia said. The population responded with remarkable enthusiasm, reelecting Orlando with an impressive 70 percent of the vote in 1997.

Still, unemployment in the city, as in much of Southern Italy, is over 20 percent. The Mafia, although under great pressure after countless arrests and trials, is still very much alive. While heroin trafficking has been seriously disrupted, the Mafia has reacted by putting more pressure on storekeepers to pay for protection. While reelecting Orlando almost unanimously, Palermo also elected as president of its provincial government a man whose brother was arrested for hiding a major Mafia boss in the family’s country house outside the city. Longstanding systems of patronage remain deeply entrenched in Sicilian life. “People still believe that you need the right ‘recommendation,”‘ Battaglia said, “the right connections to get a job, even in the university or in the hospital. The damage the mafiosi and the politicians have done to this people: they corrupted everyone, in their heads.”

Perhaps the most flagrant symbol of the squalid backwardness of Palermo is its water system. Water still runs only every other day in most Palermo neighborhoods—rich and poor. In fact, the city has enough water, but for many years its plumbing system, part of the city’s Mafia-patronage network, lost nearly half its water through leaks. At the same time, many of the city’s private wells were controlled by high Mafia bosses, who sold water (which is supposed to be public property) back to the city for a handsome profit. The Orlando administration has confiscated the Mafia-owned wells and has set to work on repairing the leaky pipe system. Orlando has often said that his goal is to restore Palermo to its proud place among the cities of Europe. If he can make good on his promise of providing water every day, as now seems at least possible, he will have gone a long way toward achieving that goal.

This Issue

July 15, 1999