1.

“To overturn the appointed times, to obliterate the divine plans, the storms gather to strike like a flood. [The gods] An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag have decided its fate—to overturn the divine powers of Sumer…to destroy the city…to take kingship away from the Land [of Sumer]….

The people, in their fear, breathed only with difficulty. The storm immobilized them…. There was no return for them, the time of captivity did not pass…. The extensive countryside was destroyed, no one moved about there. The dark time was roasted by hailstones and flames. The bright time was wiped out by a shadow. On that bloody day mouths were crushed, heads were crashed. On that day heaven rumbled, the earth trembled, the storm worked without respite…. The foreigners in the city even chased away its dead…. There were corpses floating in the Euphrates, brigands roamed the roads…. In Ur people were smashed as if they were clay pots. The statues that were in the treasury were cut down….”

The Lamentation Over Sumer and Ur, from which these passages come, was composed four thousand years ago in the aftermath of an invasion by the Elamites of Iran that brought the Sumerian kingdom of Ur to an ignominious end. This was a fittingly dramatic turning point for what our calendar marks as the transition from the third to the second millennium BC. After some twenty years of incursions, in 2004 BC the Iranian army finally breached the walls of Ur and carried off its last king, Ibbi-Suen, into the mountains: “like a bird that has flown its nest,” as the poet puts it, “he shall never return to his city.”1 The rich cities of Sumer, in present-day southern Iraq, were overrun and from the ensuing desolation emerged a vivid literature of lamentation that bewailed the destruction of temples, cities, agriculture, and all civilized life.

It is a cruel mirroring of history that the third millennium of our own era should likewise have begun with an invasion of Sumer, one in which the culture of Iraq is again under dire threat. And within weeks of the fall of Baghdad the most ambitious exhibition ever mounted on the art of the very cities sacked by the Elamites opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition served to highlight both the extraordinary richness of Mesopotamia’s cultural heritage and the corresponding magnitude of the loss suffered when many unique and supremely important works of art were stolen from the Iraq National Museum between April 10 and 12 of this year.

After much initial confusion, the scale and significance of the looting are gradually becoming clearer. Initial estimates of 170,000 missing objects were hasty extrapolations from reports that “everything” was gone. It soon turned out that many of the showcases were empty because the museum’s staff had removed the important objects to more secure locations, and that most of the collection was still intact (more or less) in the storerooms. This created something of a backlash. Having initially denounced the scandal of troops being stationed at the oil ministry while one of the world’s great museums was looted—“protecting Iraq’s oil but not its cultural motherlode”2—much of the press has since played down the disaster as overblown. This is not the case. The quantities of works stolen were substantial and, more to the point, their cultural significance immense.

A recent official estimate3 is that around forty major works were taken from the main public galleries, including the Warka Vase (later returned) and the Warka Head—two of the greatest masterpieces of Sumerian art, found at the site of ancient Uruk (modern Warka) in Southern Iraq. They also included Assyrian ivories, a large copper sculpture of a hero, and a number of other irreplaceable works. Much more was taken from the storerooms, including nearly all of the museum’s collection of cylinder seals—some 4,800 small stone cylinders carved in intaglio with miniature figured and decorative scenes that were rolled over damp clay tablets. The finest of these are exquisite and powerful works of art. Also gone are much jewelry, sculpture, metalwork, and ceramics.

At the urging of mosque leaders and museum authorities, some objects were brought back in the days immediately after the looting, and many more have since been seized both in Iraq and in customs and police operations in Jordan, Italy, Britain, and New York. As of July 11, a total of 13,515 objects had been confirmed as stolen, of which 10,580 were still missing, including all but a handful of the most important works.

As terrible as these losses are, even greater damage has been done in the months since the fall of Baghdad by the extensive, organized, and in some cases mechanized plundering of archaeological sites in the Sumerian heartland of southern Iraq. After the first Gulf War there were reports of illicit excavations and of unusual quantities of “fresh” artifacts reaching Western markets. During the past four months clandestine digging on a much greater scale by AK-47-toting bands has again been rampant at several important Sumerian sites. Some are already almost entirely gone; others are riddled with trenches and tunnels. “The looters stop at nothing,” says Pietro Cordone, head of cultural affairs in the Coalition Provisional Authority, “they use trucks, excavators, and armed guards to steal objects of great value without being disturbed. We’ve tried everything to end this systematic pillaging, military patrols at the site and helicopter overflights, but so far we haven’t been successful.”4 Officials on the ground still report a lack of funding for the basic necessities of site protection—guards, vehicles, and guns. This is where the Bremer administration, UNESCO, and other supranational organizations should concentrate their resources, shutting down the looting at its source.5 What has happened in recent months is already among the worst mass desecrations of cultural sites in our lifetime, perhaps the worst. If more time is lost before the sites are protected effectively we shall be in need of a lamentation over Sumer and Baghdad worthy of the Sumerian poets.

Advertisement

2.

The cities of Mesopotamia (Greek for “between the rivers,” corresponding to modern-day Iraq plus easternmost Syria) lie mostly under rounded mounds of weathered mudbrick, the inconspicuous tombstones of deserted settlements that can easily be taken for features of the natural landscape. Apart from a few better-preserved ziggurats (staged temple-towers), there is little in Iraq to compare with the dramatic standing monuments of the Mediterranean, and it was therefore visited and studied much less by the early pilgrims and antiquarians who, from medieval times, reopened Western eyes to the Holy Land and Egypt.

All this changed in the 1840s when northern Iraq became the scene of the most substantial excavations ever undertaken in the Near East. The French were first in the field in 1842 at Nineveh and, from 1843, at Khorsabad, the eighth-century-BC capital of the Assyrian king Sargon II. But they were soon outshone and outmaneuvered by a young British traveler and adventurer, Austen Henry Layard. En route to Ceylon, the twenty-eight-year-old Layard became intrigued with stories of buried remains in the mounds near present-day Mosul which turned out to be ancient Nineveh and Nimrud, the two most fabled capitals of the Assyrians.

Within days of starting the digging at Nimrud, Layard hit upon the first of eight palaces of the Assyrian kings dating from the ninth to seventh centuries BC, which he and his assistant eventually uncovered there and at Nineveh. In amazement they found room after room lined with carved stone bas-reliefs of demons and deities, scenes of battle, royal hunts and ceremonies; doorways flanked by enormous winged bulls and lions; and, inside some of the chambers, tens of thousands of clay tablets inscribed with the curious, and then undeciphered, cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) script—the remains, as we now know, of scholarly libraries assembled by the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal. By later standards it was treasure-hunting rather than archaeology, but after a few years of excavation in difficult political and financial circumstances, Layard had succeeded in resurrecting for the first time one of the great early cultures of Mesopotamia. He never made it to Ceylon.

The most spectacular finds were shipped back to the British Museum, where the Victorian fascination with the Bible assured these illustrations of Old Testament history a rapturous reception. By the early 1850s, progress in reading the Assyrian-Babylonian script had allowed names and events to be attached to the images, among them Jehu, the ninth-century-BC king of Israel (shown paying obeisance to King Shalmanesser III), and the siege of Lachish in Judah by Sennacherib. Layard’s account of his discoveries, Nineveh and Its Remains (1849), soon had a huge success: “the greatest achievement of our time,” according to Lord Ellesmere, president of the Royal Asiatic Society. “No man living has done so much or told it so well.” An abridged edition (1852) prepared for the series “Murray’s Reading for the Rail” became an instant best seller: the first year’s sales of eight thousand (as Layard remarked in a letter) “will place it side by side with Mrs. Rundell’s Cookery.”

Work on the decipherment of the language of the Assyrian inscriptions was making good progress while Layard was in the field, partly owing to his discoveries. But the key to cracking the cuneiform script lay elsewhere—in a trilingual inscription of the Persian king Darius carved on the face of a cliff at Behistun in western Iran around 520 BC. (In all, the cuneiform script was used for over 3,500 years.) One of the three versions of the text used a much simpler cuneiform script with only around forty characters, which scholars soon realized must be alphabetic. Even before Layard’s excavations, by making some inspired guesses about likely titles and names, they had deciphered this script and shown the language to be Old Persian, thus of the Indo-Iranian language family (a close relative of Indo-European). Having determined the general meaning of the three texts, scholars now confirmed that the second version, written in the much more complex cuneiform script (some three hundred characters) of the tablets from Assyria, was, as many had suspected, a Semitic language (i.e., cognate with Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic)—what we now know as Babylonian.6 Many texts could be read reasonably well by the time Layard’s finds started arriving in England, but the decipherment was not officially declared to have been achieved until 1857, when four of the leading experts (including W.H. Fox-Talbot, one of the inventors of photography) submitted independent translations of a new inscription and all were shown to be in broad agreement. After two and a half millennia, the Assyrians had again found their voice.

Advertisement

What the tablets said continued to cause a stir, especially when it threw light on the Bible. The most celebrated episode took place in 1872 when a young curator at the British Museum, George Smith, found among the tablets from Nineveh one that bore the story of how a Babylonian hero had survived a devastating flood:

On looking down the third column [of the tablet], my eye caught the statement that the ship rested on the mountains of Nizir, followed by the account of the sending forth of the dove, and its finding no resting-place and returning. I saw at once that I had discovered a portion at least of the Chaldean account of the Deluge.7

A Babylonian Noah! The London Daily Telegraph offered to fund an expedition to look for the missing part of the tablet. Smith duly set out, and on only his fifth day of searching through the spoil heaps of Nineveh—with luck that must have seemed divinely inspired—found a tablet fragment that filled most of the gap in the story.

The texts from Assyria were written in two closely related Semitic languages: Assyrian and Babylonian, spoken by the ancient inhabitants of northern and southern Mesopotamia respectively. As the prestigious language of higher learning, Babylonian was also used in an archaizing dialect throughout the land for literary works and royal commemorative inscriptions. So far things were much as an erudite Victorian would have expected from his reading of the Bible, where Ashur (the name of the first Assyrian capital and of the nation’s tutelary deity) appears among the descendants of Noah’s son Shem (Genesis 10:22). But the Nineveh tablets included also some bilingual texts in which the Babylonian version was accompanied by a totally different and so far mysterious language. This used the same script as Babylonian-Assyrian (and could therefore, to some extent, be read phonetically) but the language bore no relation to them, or indeed to any other known tongue. Some scholars even argued that it did not represent a real language at all but was a secret code for recording sacred knowledge by the Babylonian priests.

The issue was put to rest in the 1870s, when excavations by the French at Tello (ancient Girsu) in the south of Iraq uncovered sculptures and other objects bearing unilingual inscriptions in this language, in a clearly much earlier stage of the script (now dated around 2600–2100 BC). In the 1880s an American team began working at Nippur (which turned out to be the Sumerians’ religious capital) and found thousands more tablets recording (as we now know) literary, mythological, mathematical, and other compositions, the refuse from scribal schools from around 1700 BC. The Sumerians, creators of the earliest of all Mesopotamian civilizations, had now arrived.

3.

But who exactly were they? Like the later Assyrians and Babylonians, the Sumerians are defined for us by their language: to be a Sumerian, whatever it meant five thousand years ago, today means a Sumerian-speaker. The language itself is not inflected as Semitic and Indo-European languages are, but agglutinative: grammatical and other elements are added on as prefixes and suffixes. Its slow and painstaking linguistic analysis has been one of the triumphs of modern philology. The texts can now be translated with reasonable confidence, though many uncertainties remain.

From the archaeological remains of those who wrote and spoke Sumerian it has been possible to reconstruct much of how they lived, their arts and crafts, religion, history, and so on. But there is virtually no evidence that bears directly on the Sumerians’ ethnic or racial identity; nor indeed is it clear that these anthropological categories are really useful at this remote date. The early Near East was polyglot and multicultural. Mesopotamian scribes of the third millennium spoke and read Sumerian, Akkadian (the Semitic ancestor-tongue of Babylonian and Assyrian), and sometimes a third language as well. Shulgi, king of the Sumerian city of Ur and a great patron of learning, claims to have spoken no fewer than five. The texts speak of interpreters (including one for “Meluhhans,” i.e., people from the Indus Valley in Pakistan), and we see parents with foreign names giving their children Sumerian or Akkadian names so they will blend in. Many times in Mesopotamian history invading peoples were absorbed into the existing population and culture. Clearly language and culture mattered, but just as clearly people moved around and were able to deal with other ways of speaking and living.

The term “Sumer” derives from “shumeru,” the name for Sumer used by the Akkadians, who lived alongside the Sumerians in the heartland itself (the region from Nippur south to the head of the Gulf) and predominated just to the north in Akkad (northern Babylonia, around modern Baghdad). The Sumerians themselves called their land kiengi(r),8 or just “the land,” and described themselves as “the black-headed ones.” When and from where they first settled near the Euphrates was much debated a generation ago, but without any clear consensus. People had settled the region and were growing crops by irrigation before 5000 BC; the best we can say is that the urbanized people who, before 3000 BC, first wrote Sumerian emerged out of this agricultural way of life and tradition without any obvious break.

That story is what school textbooks like to call the birth of civilization, and though, like all clichés, this is an oversimplification, the uniqueness of what happened in early Sumer and its significance for world history can hardly be exaggerated. The main source of this revolution seems to have been the city of Uruk (biblical Erech, modern Warka) in southern Sumer, which by circa 3400 BC had become the largest permanent urban settlement ever created. At its core lay two monumental temple complexes dedicated to the sky-god Anu and the goddess of love and war, Inana. In and around these temples were found what are still the earliest writings from anywhere in the world, the pictographic system of recording on clay tablets that evolved into cuneiform, along with sophisticated architectural, technological, and artistic traditions illustrated by the Warka Vase and Head. Life in and around the temples was supported by well-coordinated religious, social, and presumably political administrations.

As more recent excavation has proved, the early Sumerians were also active colonizers, if not imperialists. In the centuries before 3000 BC, colonies and outposts of the “Uruk culture” were established hundreds of miles away, along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Syria and Turkey, and in western Iran, presumably to procure metals, stones, timber, and other raw materials. It is at this time also that Sumerian cylinder seals, artistic motifs, and other cultural traits are found in Egypt, suggesting some Mesopotamian stimulus in the emergence of a distinctive culture under the first dynasties there.9 How the Uruk network was achieved and maintained we do not know, but its success cannot be doubted: by the early third millennium the city had grown into a massively walled metropolis of over 1,300 acres.

The earliest writings provide a window into the minutiae of everyday life in early Sumer for which nothing else in the ancient world can prepare us. The earliest pictographic texts (circa 3400–3200 BC) deal primarily with agricultural administration—lists of livestock, disbursements of grain, and so on. But already there are a few lists of types of animate and inanimate objects—evidence of the Sumerians’ peculiar predilection for categorizing the universe. The script had taken on its distinctive wedge-shaped character by the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period (circa 2900–2350 BC) during which other genres gradually made their appearance: literary texts, proverbs, hymns and cultic compositions, and historical narratives about border disputes between rival city-states such as Lagash, Umma, Ur, and Kish.

Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2112–2004 BC), the last and most glorious flourishing of Sume-rian culture, were great patrons of literature and learning, none more so than the multilingual Shulgi—“in my palace no one in conversation switches to another language as quickly as I do”—who claims to have “learned the scribal art from the tablets of Sumer and Akkad…. The academies are never to be altered,” he declared, “the places of learning shall never cease to exist.”10 It was probably in these academies that much Sumerian literature was standardized into something like the form we see it in the students’ exercises from Nippur three hundred years later. Scholarship of the past fifty years has done much to bring this sophisticated world back to life in epics of heroic bravery and combat (most famously Gilgamesh); the loves and rivalries of the gods; the travails of their favorites on earth; proverbs and fables; and in royal and sacral hymns of praise.11 Underneath it lies a much weightier mass of mundane ephemera from everyday life—hundreds of thousands of texts that make Mesopotamia the most fertile ground for social and economic history of any ancient culture.

4.

Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium BC from the Mediterranean to the Indus closed on August 17 but its beautiful and scholarly catalog preserves much that was exciting about it. Having sold some six thousand copies it may also have done more than any book since Leonard Woolley’s Ur of the Chaldees (1929) to raise public consciousness of the ancient Near East in this country, and at an especially important time.

The cultural heart of the show was Mesopotamia, which is also treated in far greater depth than its neighbors in the catalog. Despite its title, the exhibition was about much more than art (many objects qualified at best as craft, but are important for other reasons) and rather more than cities (many works came from towns and small trading entrepôts). But as a leitmotif for the exhibition, the city was the right choice. Urbanism lay at the heart of what was new about culture at this time; and cities were the source of much of the greatest art, which provides the easiest point of entry for visitors today, many of whom will be unfamiliar with this region. This unfamiliarity was no doubt a large part of the exhibition’s raison d’être. Indeed, in some ways, the ancient Near East is a more exotic and alien land to New Yorkers today than it was to Londoners in Victorian times—certainly no subsequent writer has had anything like Layard’s success—and popular appreciation of its artistic achievements has fallen even further behind that of Egypt and the classical world.

The first room of the exhibition was enough to show how unbalanced this perception is. Already in the Uruk Period (circa 3400–3000 BC), the arts of Sumer and neighboring Proto-Elam12 (southwestern Iran) have the confidence and refinement of a style and approach to art that are no longer groping toward something else but have arrived at a visual language fully adequate to their creators’ expressive and aesthetic intentions. (This cannot so confidently be said of Egyptian art of the same era.) Two supremely beautiful sculptures from Proto-Elam—a lioness-demon with her clenched paws braced against her chest (see illustration on page 18), and a silver kneeling bull in human attitude, dressed and holding up a vase with his front hoofs—are gems of early naturalistic fantasy. Miniature, low-relief versions of these same subjects on cylinder seals (which become essentially two-dimensional drawings when rolled over the wet clay) show also how the idiom had been carefully adapted to the different technical and aesthetic requirements of each medium.

The rich finds from the Royal Tombs of Ur, dating from the mid-third millennium BC, are perhaps the most celebrated Mesopotamian discovery of the twentieth century. They include jewelry, lyres, vessels, and other objects all resplendently decorated in gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian. (See the Rearing Goat with a Flowering Plant on page 20.) Despite their glittering appeal as treasure, however, the artistic quality rarely rises to the level of the finest cylinder seals, where we see well-muscled heroes grappling with bull-men and lions all in a space no bigger than one inch by two. The dumpy proportions and naive-looking expressions of figures in contemporary sculptures, relief carvings, and inlay work evoke a curiously unreal, toy-like world, even when they are waging war (as in the battle scenes on the Standard of Ur and Stela of the Vultures). The wide-eyed worshiper statuettes of this period likewise leave us wondering whether, for regular-sized art, we have yet to discover the finest works by the most accomplished court artists.

There can be no doubt, on the other hand, that the succeeding Akkadian Period (circa 2350–2150 BC) was one of the pinnacles of early artistic achievement anywhere. A more intense naturalism of human and animal forms is immediately apparent, together with an adventurous expansion of composition and subject matter (in narrative, and especially mythological, scenes) and greater technical mastery in working metals and hard stones, which are now polished to a high sheen. It is a tantalizing thought that the glimpses we get from the surviving bas-reliefs of battle scenes and prisoners, bronze portrait heads of bearded kings, and mythological narratives on cylinder seals are surely only a foretaste of what lies ahead if the imperial capital of Akkad is ever found.

This sculptural tradition reaches its climax in the series of statues of Gudea and other rulers of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash around 2100 BC that were the most spectacular finds from the early French excavations at present-day Tello in Iraq. Arriving at the Louvre a generation after the fearsome depictions of the Assyrian kings in battle, these engaging images of pious stewardship suggested an altogether more humane and appealing world; they have rightly come to be recognized among the masterpieces of ancient art. Gudea is usually shown standing, wearing a cap with rows of curls (fur?), his hands clasped at his chest in dutiful worship of Ningirsu (later known as Ninurta, the Babylonian war-god), his tutelary deity. One famous variant shows him as an architect, seated with the plan of Ningirsu’s temple on his lap. This is an image of the ruler as mediator between earth and heaven, as shepherd of his flock, as architect of their prosperous future—almost a Mesopotamian buddha. Not surprisingly, it has struck a chord with museumgoers, and especially with artists, ever since.

5.

The world of the ancient Near East outside Mesopotamia was a mosaic of disparate languages and cultures, but one showing evidence of extensive contact across very large distances. Although many of the languages remain undeciphered or unknown,13 and many of the cultures are defined solely by their archaeological remains, we can trace in considerable detail the traded goods, artistic borrowings, and other cultural exchanges between peoples from Pakistan all the way to the Aegean. It is a surprisingly large stage of interaction, one not matched until the emergence of the Persian Achaemenid empire founded by Cyrus the Great some two thousand years later. As the subtitle indicated, one aim of the exhibition was to place the civilizations of the Near East, including Mesopotamia, within this broader setting.

Fifty years ago this undertaking would have had a very clear story line: it would show how civilization, once born in Mesopotamia, was diffused to Egypt and eventually right across the Old World: ex oriente lux, “from the East, light.” The argument was founded on findings of distinctively Mesopotamian artifacts and bureaucratic practices (writing, sealing, etc.) in Syria, Egypt, Iran, and even the Indus Valley; more rarely those of these other cultures in Mesopotamia. In some cases there was clear evidence of trade (especially along the Gulf between Mesopotamia and the Indus, and northwest with Syria); in others the suggestion of Sumerian colonies (Syria and Iran). But often, as with Egypt, quite what these “cultural contacts” amounted to in human experience remained unclear.

While the evidence for such a diffusionist picture has multiplied dramatically, however, interpretation has headed in precisely the other direction—away from cross-cultural influence toward independent invention and regional distinctiveness. Partly this resulted from the realization that the idea of diffusion as a passive, one-way transfer of cultural capital from one place to another was flawed; even where influence can be demonstrated it is a multidirectional and selective process in which “peripheries” often played as large and active a part as “cores.” The Egyptians adopted the idea of writing from the Sumerians (if indeed they did so) because it suited their own rulers’ political and social purposes. Many other cultures chose not to do so—not because they didn’t know about it or were not smart enough, but because they did not have, or did not wish to have, the political and social institutions within which writing could function as a useful instrument of coercion and control.14 But this shift, it must be said, also has more than a little to do with fashion in academic thinking, in particular the growing resistance to seeing cultures in “primary” and “secondary” tiers. If there was a quibble with the exhibition as a whole it was its reluctance, having presented the evidence, to grapple with the changing interpretations that scholars have placed upon it.

The catalog ends appropriately with a discussion of the Mesopotamian cultural tradition and its legacy through the Hebrew Bible to the West—the Sumero-Babylonian stories that parallel, to varying degrees, the Creation, the Garden of Eden, the Flood, and the Tower of Babel. The thoroughly pagan Gilgamesh, Sumer’s most famous son, has been much harder to identify in art than his literary renown would suggest, and there were no certain images of him in the exhibition. A tragic hero whose great achievements as king of Uruk still cannot bring him the one thing he truly wants—immortal life—Gilgamesh is a sympathetic and human foil to the Egyptian kings who revel so comfortably in their assured divinity. He has of course had an immortality of sorts in the legacy that this exhibition triumphantly proclaimed. We can only hope that the violence still being inflicted on it in the mounds of Iraq will soon be brought to an end.

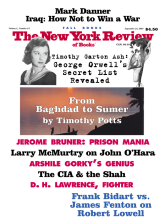

This Issue

September 25, 2003

-

1

The Lamentation Over Sumer and Ur, excerpts from throughout the text (cf. one of the preserved tablets in the Met- ropolitan Museum exhibition: cat. no. 333). On the lamentations and Sumerian literature generally, see the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL): www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac .uk (lamentations at /catalogue/catalogue2.htm#LAMENT).

↩ -

2

Frank Rich, The New York Times, April 27, 2003.

↩ -

3

Briefing by Colonel Matthew Bogdanos in London, July 11.

↩ -

4

The Jordan Times, August 1, 2003.

↩ -

5

The Italian carabinieri, who have taken over responsibility for the area of Nassyriah from the United States Marines, have recently begun some patrols at night, recovering two groups of looted artifacts.

↩ -

6

Assyrian, the other main language of the tablets from Nineveh, was so close to Babylonian that there was no need to decipher it separately. The third version of the Behistun inscription turned out to be Elamite, the principal administrative language of the Iranians. Since it is a linguistic isolate, its decipherment took considerably longer and it remains today relatively poorly known.

↩ -

7

The Chaldeans were a tribe who inhabited southern Babylonia; in the Bible (and for Victorian scholars) the term is used more or less interchangeably with “Babylonians.” See R. Campbell-Thompson, A Century of Exploration at Nineveh (London: Luzac, 1929), p. 49.

↩ -

8

Its meaning is unclear; it is made up of elements meaning “place,” “lord,” and “noble.”

↩ -

9

This is the one point where the virtual exclusion of Egypt from the exhibition (only two objects) leaves out of account a crucial aspect of Mesopotamia’s seminal influence on its neighbors.

↩ -

10

See the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, www-etcsl.orient .ox.ac.uk.

↩ -

11

See the ETCSL above.

↩ -

12

Since the Iranian texts from this period (clearly inspired by the earliest writing at Uruk) cannot yet be read, their identification as Elamite is not certain.

↩ -

13

Aside from the languages which can be classified as Semitic (Akkadian, Eblaite, Amorite, Aramaic, Ugaritic, Canaanite, Hebrew etc.) or Indo-European/Iranian (Hittite and others in Turkey, Old Persian and Median), all the known languages of the ancient Near East are isolates with no known relatives or descendants.

↩ -

14

See articles by John Baines and Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky in Culture through Objects: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of P.R.S. Moorey, edited by T.F. Potts et al. (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2003), pp. 27–75.

↩