1.

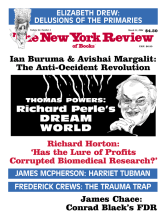

The invasion of Iraq and the planting of an American army in the heart of the Middle East have encouraged one of the war’s intellectual architects, Richard Perle, to think that the United States may be pulling up its socks at last. The overthrow of Saddam Hussein, following the defeat of the Taliban in Afghanistan, is the fruit, in Perle’s view, of a bracing new clear-eyed toughness in dealing with the enemies of democracy. But the job is far from over and Perle, in the new book he has written with David Frum, worries that “many in the American political and media elite are losing their nerve for the fight.” The enemies are many, friends are few, and summertime soldiers on the left, as Perle sees it, want to call a truce in the war on terror in “the hope that…somehow the threat will disappear on its own.”

About the source of the threat Perle expresses no doubt. It comes from “a radical strain within Islam” driven by “murderous hatred of the United States” to carry out terrorist attacks against America and its friends. Despite a vigorous worldwide counter-terror campaign, “Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and Hamas still plot murder”; and the willingness of state sponsors to arm them with weapons of mass destruction threatens “even our survival as a nation.” But where might the terrorists get these weapons, now that Iraq has been occupied? “North Korea claims already to possess some bombs,” Perle argues. “Iran is very close—perhaps three years away, in the optimistic view of US intelligence, maybe twelve to eighteen months, by the less sanguine Israeli estimate.”

We have heard such alarms before, most recently about Iraq, but Perle brushes aside the failure to find the weapons which were cited to justify the American invasion. “The critics’ emphasis on stockpiles,” he writes, “seems to us seriously misplaced.” Iraq fortunately was stopped in time, but other outlaws remain: “Why let an enemy grow stronger?” At the top of the enemies list are Iran and North Korea, which not only engage in terror but support terror. “Both regimes present intolerable threats to American security,” he insists. “We must move boldly against them both and against all the other sponsors of terrorism as well: Syria, Libya, and Saudi Arabia. And we don’t have much time.”

That’s quite a list of target countries—seven nations in all, including the two already defeated and occupied. Does “moving boldly” mean invasion to remove the regimes in all of them? Maybe yes, maybe no. Only a month after the terror attacks of September 11 Perle told an interviewer for Frontline that the resolute action he recommended in Afghanistan and Iraq might be enough to caution others:

Because having destroyed the Taliban, having destroyed Saddam’s regime, the message to the others is, “You’re next.” Two words. Very efficient diplomacy. “You’re next, and if you don’t shut down the terrorist networks on your territory, we’ll take you down, too.”

Few thought Perle’s plan to invade Iraq reasonable or likely when he first began to defend the idea in public. It seemed over-bold even after President Bush, in his second State of the Union speech in January 2002, included Iraq in the “axis of evil”—a phrase partly invented by Perle’s coauthor, David Frum, who put the words “axis of hatred” in an early draft of the President’s speech. But Perle was not speaking lightly. As a member of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board, he was a figure of significance in Washington, close to officials close to the President, and last year’s relentless march to war is ample evidence that Perle’s views were taken seriously in the Bush White House.

Of course Perle was not alone in beating the drum, but he is the first of the Washington hard-liners to have written at length about the strategy behind the war on terror, a fact which makes An End to Evil important and timely. The unraveling of the official case for war, based on intelligence claims, now exploded, that Saddam Hussein had stockpiles of banned weapons and vigorous programs to build more, makes it all the more urgent to understand why President Bush was so determined to go to war, what he hoped to achieve by it, and what we ought to expect if the war policy is confirmed by the President’s reelection in November.

Richard Perle and David Frum share the title page and the copyright notice in An End to Evil, but to this reader, at least, it seems that the book belongs in some sense to Perle alone. I do not mean to suggest that Perle did all the work of writing, or that he and Frum did not reach agreement on the text before it went to the printer, or that Frum did not bring experience of his own to the project. But it is Perle who is the one with the public persona, who has held policy-level jobs in two administrations, who is often in the news, and whose pugnacious, bravura intellectual style gives the book its flavor. And above all, it is Perle who has a long history of promoting the hard-line, or “realist,” approach to American foreign policy.

Advertisement

Perle has been a fixture on the Washington scene since 1969, when he joined the staff of Senator Henry Jackson, a hard-line Democrat deeply opposed to the whole idea of détente with the Soviet Union. Jackson was a man of the anti-Communist, working-class left, the son of a union man, and he was a combative advocate of keeping ahead in the nuclear arms race, fighting the Communists in Vietnam, and pushing the Soviets hard to open their borders to Russian Jews trying to emigrate—an effort in which he was ultimately successful. Perhaps a quarter of Israel consists now of former Russian Jews and there are those who think Jackson’s hard line also deserves a significant share of the credit for the eventual collapse of communism, the freeing of Eastern Europe, and the breakup of the Soviet Union. It is not quite clear from An End to Evil, or from things Perle has written and said elsewhere, whether he brought a fierce approach to foreign affairs with him to Washington or learned it during the eleven years he spent at Jackson’s side. But hard-line is what Perle is.

“Hard-line” is a word defined by thirty years of examples. At various times hard-liners, Perle often among them, pushed for more and better nuclear weapons, ridiculed the notion of “arms control,” argued for victory in Vietnam, were ready to spread the war into Laos, Cambodia, and even North Vietnam itself, supported Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, wanted to kick the Sandinistas out of Nicaragua, argued that an all-out arms race would spend the Soviet Union into bankruptcy, pushed for American recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, backed the scrapping of the anti-ballistic missile treaty, supported a clear commitment to defend Tai-wan, and expressed contempt for the United Nations. To be hard-line involves the willingness to use force, realism about using money and power to get one’s way, impatience with feel-good idealism, all-out backing for friends, and contempt for efforts to placate enemies. “Hard-liners” share an Old Testament view of the world, promise an eye for an eye, know what they want, and never forget an injury.

But perhaps most important of all, hard-liners are comfortable with the fact of overwhelming American military and economic power, and argue that it ought to be used without apology to chastise enemies, support friends, and get what America wants. In a recent column in The Wall Street Journal Perle and Frum argue that most definitions of hard- and soft-line get things exactly backward. “It is the soft-liners who are driven by ideology, who ignore or deny inconvenient facts and advocate unworkable solutions,” they write. “It is the hard-liners who are the realists, the pragmatists.” In their view the confusion is nowhere more evident than in the discussion of Israel and the Palestinians, where East–West friction brings almost daily bloodshed. Hard-liners face facts, Perle and Frum argue: Arafat will never make peace with Israel. Period. But the soft-liners, including many in the US State Department, “cling to this belief” that dialogue, negotiation, compromise will bring a settlement at last.

Perle’s devotion to Israel runs deep. Decades of war and near-war with hostile neighbors have made the country tough and self-reliant, in many ways the ideal archetype of hard-line realism as state policy. Perle has been a director of the Jerusalem Post, a consultant for Israeli weapons manufacturers, a member of the board of advisers of the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, and one of the coauthors of “A New Strategy for Defending the Realm,” an influential paper recommending a hard-line policy to Benjamin Netanyahu, Sharon’s predecessor as Israeli prime minister. In an interview with Ben Wattenberg on PBS in November 2002, Perle was asked why “these neoconservative hawks” were mainly Jewish, and how he answered charges that there was a “hidden agenda” in his call for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein—that, as Perle restated the question in his reply: “We are somehow motivated not by the best interest of the United States but by Israel’s best interest.” Behind the first, Perle replied “there’s clearly an undertone of anti-Semitism,” and the second claim, in his view, gave off the same aroma. “It’s a nasty line of argument,” he said, “to suggest that somehow we’re confused about where our loyalties are.”

Advertisement

Perle strikes me as a little nervous and defensive on this point. Why not admit openly that of course the fate of Israel is much on his mind? Anglophiles of yesteryear did not apologize for arguing that it was in America’s best interest to come to the aid of Britain in 1940, and Polish Americans did not worry in silence about the fate of Lech Walesa. Complex loyalties are part of the American style. But the decision to attack Iraq was made by President Bush, whose loyalties are not complex. Bush has no history as a hard-liner himself but he seems to have adopted a hard-line position as a governing style, telling enemies abroad what he will not tolerate, pushing for his agenda without compromise at home, taking the support of allies like Britain’s Tony Blair as if it were his by right, dismissing the hesitations of other longtime friends as somehow meanly motivated. Former Secretary of the Treasury Paul O’Neill reports in his quasi memoir of two frustrating years in the Bush administration, The Price of Loyalty,1 that Bush was rigid on questions of policy. “I won’t negotiate with myself,” he often said, meaning, in O’Neill’s view, that once the President had taken a position it was set in concrete, and no one should expect to revisit its rationale. The President’s frequent use of the word “evil,” echoed by Perle and Frum, is a sign that he is not about to negotiate with himself when the question on the table is how to deal with enemies.

This firmness is about all Bush shares with Perle. Intellectually they are poles apart; Bush sticks to the official line with numbing tenacity while Perle has a lively comment about everything. There is a dazzling, at moments disorienting extravagance to An End to Evil, like the grand climax to an evening of fireworks. No hyperbolist could exaggerate the range or confidence of Perle’s opinions. It seems that success in defeating terror is going to require changing pretty much the whole of the rest of the world as well—from the culture of bureaucracy in the CIA to the position of Britain in Europe, from the timidity of the State Department to the irresolution of the United Nations, from the foot-dragging of Pentagon generals to the ingratitude of old allies like France and Germany. Among the obstructionists scolded by Perle are not only Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schröder, but former President Clinton, the State Department’s Richard Armitage (for his “incredible statement that he considered Iran to be a ‘democracy'”), Brent Scowcroft and Richard Haass (for “almost certainly” instructing US Ambassador April Glaspie to shrug off Saddam Hussein’s plans to invade Kuwait in the summer of 1990), CIA director George Tenet (“He has failed. He should go”), and even the first President Bush, because he “tried to prevent the Soviet Union from disintegrating“—a failure of nerve so egregious that Perle puts the words in italics.

An End to Evil makes so many charges against enemies abroad, accuses so many people of cant and confusion, issues so many warnings of imminent peril, and proposes so many bold undertakings that it is difficult to find the idea at the core of the book—identification of the danger that America faces, and the strategy Perle believes will bring victory. When the reader gets a grip on the danger at last it turns out to be a kind of mirror-image of the President’s claim that terrorists hate America for what it is—Western, tolerant, democratic, pluralist, materialist, and so on. In Perle’s view the source of Islamic terror is to be found in who they are—blocked at every turn in societies where hatred and violence are the only means of self-expression:

Take a vast area of the earth’s surface, inhabited by people who remember a great history. Enrich them enough that they can afford satellite television and Internet connections, so that they can see what life is like across the Mediterranean or across the Atlantic. Then sentence them to live in choking, miserable, polluted cities ruled by corrupt, incompetent officials. Entangle them in regulations and controls so that nobody can ever make much of a living except by paying off some crook-ed official. Subordinate them to elites who have suddenly become incalculably wealthy from shady dealings involving petroleum resources that supposedly belong to all…. Deny them any forum or institution—not a parliament, not even a city council—where they may freely discuss their grievances. Kill, jail, corrupt, or drive into exile every political figure, artist, or intellectual who could articulate a modern alternative to bureaucratic tyranny…. [Ensure] that the minds of the next generation are formed entirely by clerics whose own minds contain nothing but medieval theology and a smattering of third world nationalist self-pity. Combine all this, and what else would one expect to create but an enraged populace….

Perle’s argument for an aggressive assault on “terror,” by which he means “all regimes that use terror as a weapon of state against anyone, American or not,” begins with the assumption that no strategy can succeed which does not fundamentally alter the world that breeds terror. The most important change—the one that must precede and open the door to all others—would be to replace closed, authoritarian governments with open ones—in a word, bring democracy to the Islamic world. This bold idea has also been embraced by President Bush, who told an audience at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington a year ago that “the world has a clear interest in the spread of democratic values, because stable and free nations do not breed the ideologies of murder. They encourage the peaceful pursuit of a better life.” The invasion of Iraq did not merely end the possibility that Saddam Hussein would give nuclear weapons to Osama bin Laden; it created an opportunity to build a freer, fairer, more open society to serve as a beacon of hope in the Islamic world, “and it is vital,” Perle writes, “that we succeed.”

Of this bold scheme, after a day’s reflection, one might say what Jake Barnes told a wistful Lady Brett in The Sun Also Rises—“Isn’t it pretty to think so.” Perle’s plan to transform the Islamic world beginning with Iraq, an idea shared by Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and others in Washington, represents what is possibly the single most ambitious program to change the world in American history. Not even the fabled Marshall Plan for rebuilding Europe after World War II matches it for imagination, generosity, sweep—and difficulty. As I write, success in the democracy-building effort in Iraq seems far from certain. Rather than one free state with a newborn democracy, it seems that Iraq is breaking into three super-nationalist, mutually hostile mini-states comprising the Kurds in the north, the Sunnis in the center, and the Shiites in the south. In Afghanistan the military victory of late 2001 seems to be slipping away as the Taliban proves to have life in it yet.

I have no quarrel with Perle’s vision of what Iraq might become. “If Iraq’s new legislature is freely chosen,” he writes,

…if its bureaucracy is generally honest and competent and its courts are fair, if Iraqis can engage in private business without harassment and favoritism, if Iraq’s different communities can live without fear—then that is an achievement as impressive as anything the democratizers could hope for.

This is nobly said. Who would fault the dream? Where my credulity fails is with the implicit claim that the scope of this grand intervention is the brainchild of “realists” and “pragmatists.” What makes Perle think that the United States can do for the warring factions of Iraq, burning with the grievances of centuries and still raw from thirty years of oppression under the police state of Saddam Hussein, something it has conspicuously failed to do over half a century for the Israelis and the Palestinians?

2.

Richard Perle has been living with the dilemmas at the heart of An End to Evil for many years—at least since the first Persian Gulf War of 1991, when the United States, in his view, made a ghastly mistake in failing to overthrow the regime of Saddam Hussein, an error he credits (gently here) to Colin Powell and the first President Bush. Since the terrorist attacks of September 11 he has argued his position with renewed fervor “to journalists from around the world, almost all of whom eventually work their way up to the one big question: Is the war on terror a Zionist plot?”

Are those really the words used? I doubt it. I’m guessing that the posing of the question sounds more like this: Is one of the goals of the war on terror to make the Middle East safe for Israel? With the question put that way Perle’s answer would surely be yes, and a careful search through his blizzard of obiter dicta discovers a theory about how this might come to pass. It is based on two axioms—that Hezbollah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and other military opponents of Israel are dependent on state sponsors like Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Saudi Arabia for support; and that these groups, by their resort to attacks on civilians, are on the roster of terrorist organizations and thereby pose a threat to the United States, a threat that cannot be distinguished from that of al-Qaeda. This is presumably what Perle means when he says “Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and Hamas still plot murder” and why he presses for war on “all regimes that use terror as a weapon of state against anyone, American or not.” It’s a tricky point. According to Dilip Hiro’s The Essential Middle East,2 Hezbollah and Hamas consider themselves to be at war with Israel, not the United States. Treating them as synonymous with al-Qaeda adds to the number of America’s enemies and widens the war on terror without making it easier to fight.

But President Bush seems to have adopted Perle’s inclusive definition of terror, possibly without understanding quite how clearly it commits the United States to support for Israel’s continuing occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. By declaring Israel’s enemies as our own, the inclusive definition of terror as a strategy to make the Middle East safe for Israel certainly seems more “pragmatic and realistic” than the more grandiose effort to replace the regimes in Perle’s target countries. “Moving boldly” against Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Saudi Arabia may not actually bring democracy, but it will certainly impede the flow of money and arms to Hezbollah and Hamas, bring a period of relative peace, and thereby allow Israel to put off again the difficult moment when it must give up the West Bank. Delay of the inevitable, cutting off money and arms, making life hard for opponents—those are goals realists and pragmatists can get behind.

In the world according to Richard Perle everything is clear and all choices are stark—except when it comes to the West Bank and Gaza. There he grows vague. “The Arab–Israeli quarrel is not a cause of Islamic extremism,” he writes. “The unwillingness of the Arabs to end the quarrel is a manifestation of the underlying cultural malaise from which Islamic extremism emerges.” So the suicide bombers are driven by “the under-lying cultural malaise”? It has nothing to do with thirty-five years of Israeli occupation?

On this subject alone Perle is unable to say what he thinks must be done, offering instead a bleak outline of everything that won’t work, starting with the one thing Palestinians have agreed they want—a state in the West Bank and Gaza. Perle concedes that this might be achieved, “if the United States were to denounce Israel as an illegal occupier of Muslim land, attack it, deport the Jewish population, and turn over the Temple Mount to the Palestinians….” Alas, “carving out a twenty-third Arab state in the Judaean Hills” won’t solve anything. The mini-state will be weak and small; extremists will demand more; “every great-niece or third cousin whose family once lived on what is now Israeli territory must be allowed to return.” America will have to take on the job of defending the mini-state from Hezbollah and Hamas. “In the end, we will be fighting its people on its behalf. We will have created a Palestinian South Vietnam.” Yes, yes—“a peaceful, open, and democratic Palestinian state would be a good thing,” he concedes, but “the likeliest result…will be another abject failure of the so-called peace process.” It will all end badly.

What does this mean? Perle’s answers are elliptical. “The greatest… obstacle to peace is the feeling among many people in the Arab and Muslim world that anything that was once theirs can never legitimately be anybody else’s.” Many peoples have suffered the loss of a homeland in the last hundred years, he writes. They got used to it. Jews had to leave their homes in Arab land. “They…let go of the past. The exiled Palestinians should likewise be accepted as citizens of Arab countries in which they now live.” Is Perle saying that the Palestinians ought to give up their hope of a state on the West Bank…and move away?

The hard-liner seems to have run out of ideas. China, Russia, the CIA, the State Department, “the underlying cultural malaise” in the Middle East—all these he can fix. But when it comes to the longest-running open sore in the clash of civilizations, his advice to the Palestinians is what Lucy in her role as psychiatrist used to tell the troubled Charlie Brown—“Get over it!”

That’s what decades of bloody struggle over the West Bank get by way of helpful advice in An End to Evil. After it come eighty pages on “Organizing for Victory” and how to deal with “Friends and Foes.” Firmly is the basic idea. It’s all rousing stuff in its way but hard to take seriously if not for one fact—the American army now planted in the heart of the Middle East. Anybody wondering when that army will return home should follow closely something never mentioned by Perle—the status of forces agreement soon to be negotiated between the United States and the new sovereign government of Iraq, once it is established. A status of forces agreement regulates the presence of military forces in an alien country. It’s my guess that the United States will insist on the right to maintain bases in Iraq, to supply, expand, or contract them at will, and to conduct military operations inside Iraq, or against third countries from Iraq, without requiring the permission of the host government. Anything less would be lacking in realism. The hard-liners have insisted all along that Iraq is not the only regime in the Middle East that needs changing, and the United States will need plenty of latitude if a reelected President Bush is to carry on with the hardline strategy for winning the war on terror.

This Issue

March 11, 2004

-

1

Ron Suskind, The Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O’Neill (Simon and Schuster, 2004); see Paul R. Krugman’s review in these pages, February 26, 2004. ↩

-

2

Carroll and Graf, 2003. ↩