In response to:

The 'Problem of Evil' in Postwar Europe from the February 14, 2008 issue

To the Editors:

Tony Judt’s discussion of the “problem of evil” and how best to remember the Holocaust [“The ‘Problem of Evil’ in Postwar Europe,” NYR, February 14] is both insightful and provocative. At the same time, his assumptions and conclusions are somewhat naive.

Judt’s claim that the Soviet unwillingness to commemorate the Jewish victims after the war was due to the fact that for Soviets “Hitler was above all a fascist and a nationalist. His racism was much less important” is only partially true. The Soviet unacknowledgment of the Shoah was a product of Stalin’s postwar anti-Semitic campaigns, an upsurge in popular anti-Semitism after the war, and the later anti-Semitic, often presented as “anti-Zionist,” policies of the Soviet government. Certainly prior to the pact between Stalin and Hitler in 1939 as well as during the war, when the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was actively working on behalf of the Soviet war effort, the government had no problem with calling attention to the inherently anti-Semitic nature of the Nazi regime.

Judt realizes the importance of questions that he often hears in Poland and Romania: “Why [are] Western intellectuals so particularly sensitive to the mass murder of the Jews. What of the millions of non-Jewish victims of Nazism and Stalinism?” He sees them as legitimate. What he fails to recognize is that they are fed by strong anti-Semitic tradition and currents in discussions of the war in Eastern Europe and parts of the former Soviet Union, such as Ukraine. Insensitivity to Jewish suffering and revisionist histories are indicative of these trends.

Finally, to equate any criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism is silly and perhaps dangerous. But it is equally dangerous to overlook, which is what Judt seems to be doing, the enormous destructive role that anti-Semitic theories play in anti-Israeli sentiments in most of the Middle East, be it in populist or intellectual guises. Jews may be doing well in Holland, the US, and Germany, but the attempts to downplay the potency of anti-Semitism will not aid in addressing the “problem of evil” anywhere.

Marat Grinberg

Assistant Professor

Department of Russian and Humanities

Reed College

Portland, Oregon

Tony Judt replies:

Stalin was always anti-Semitic, yes. But communism’s postwar unconcern for Hitler’s Jewish victims was not just a by-product of endemic Soviet “anti-Zionism.” That would be too easy. The antifascist coalitions and rhetoric before and after World War II rested on a broad but shallow consensus: that “fascism” (encompassing all its varieties) was undemocratic, repressive, and reactionary. Emphasis on the Nazis’ Judeophobia—or on dead Jews—would have been politically divisive at a time when popular anti-Semitism was still widespread in Europe. Thus wartime anti-fascist resistance organizations (in France and Belgium no less than Poland or Ukraine) played down the Jewish identity of Hitler’s victims. For many years after 1945 it wasn’t just Communists who felt more comfortable honoring antifascists who had fought or died for their country rather than those who were merely murdered for their “race.”

Does anti-Semitism lie behind Eastern Europeans’ irritation at Western emphasis upon Jewish victims? I’m sure it often does. But that irritation also has its roots in the West’s longstanding indifference to non-Jewish victims of both Hitler and Stalin, and it is not unreasonable for people to raise the matter. Actually it has been my impression that scholars and public officials in many parts of Central and Eastern Europe have tried hard to overcome the prejudice and ignorance of decades past.

Finally: anti-Semitism among Palestinians and other Arabs is stupid and deplorable. But far from fueling anti-Israeli sentiment, it has frequently been spawned by it. Anger and frustration at Israel’s actions disposes people to hate all Jews and believe ill of them—as we have seen in Europe’s own Muslim communities in recent years. I don’t downplay this development. On the contrary, I see it as a new and dangerous twist in the long history of anti-Jewish prejudice. One hundred years ago, anti-Semitism was “the socialism of fools” (Bebel); today it is the consolation of losers. Those who complacently attribute the Middle Eastern tragedy to resurgent anti-Semitism among dispossessed, displaced, and humiliated Arabs should know better. They are blaming the victim.

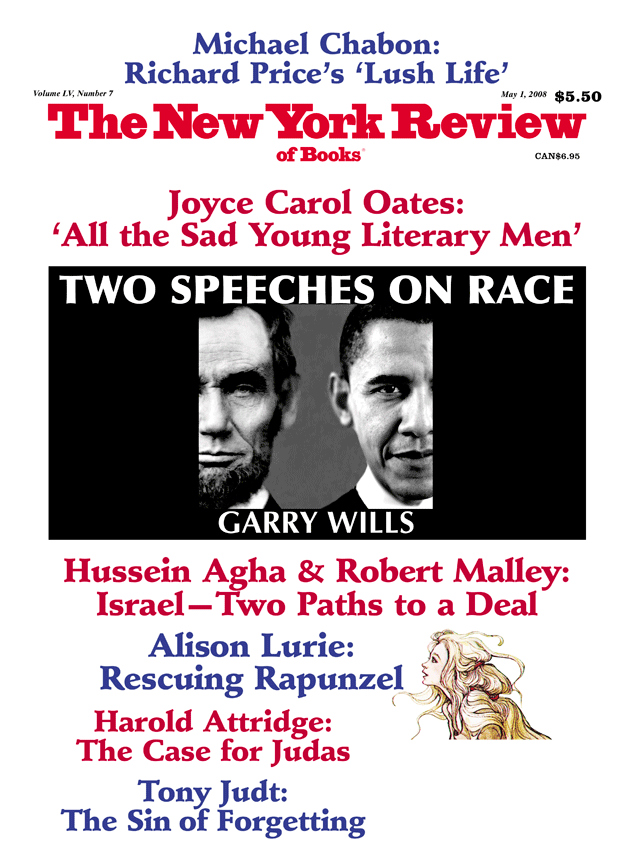

This Issue

May 1, 2008