In response to:

The Girl in the Tower from the May 1, 2008 issue

To the Editors:

In Alison Lurie’s fascinating review essay about recent Rapunzel stories [NYR, May 1], she comments on the increasing contemporary appeal of this fairy tale in an era when overseas adoptions by older parents are frequent; she also observes that most expectant mothers crave sweets rather than salad greens. I would like to suggest that the two points are more deeply intertwined than might appear: from Poison: A History and a Family Memoir by Gail Bell, I learned that parsley, when decocted in concentration, was a popular abortifacient.

Parsley, not rampion, is the herb that gives the heroine her names (e.g., Persinette) in the Italian and French variations of the fairy story which predate the Grimms. Rampion is now better known as evening primrose, but was once nicknamed the “king’s-cure-all,” as it has multiple properties, much ventilated again today. The plant isn’t directly emmenagogic, however, but recommended for regulating the menstrual cycle and preventing cramps, etc.

The Grimms, who were eager to avoid sexual innuendo in their revisions, might have preferred rampion to parsley on account of the herbs’ different popular uses and sought to bury a different story, one uncomfortably close to daily life. The expectant mother in the fairy tale, who steals herbs from the witch, might be trespassing in the garden of a cunning woman expert in such matters, and, when discovered, might indeed agree instead to hand over the baby at birth. The witch’s later ferocious desire to guard Rapunzel from wandering males’ attention, and her fury when the young girl becomes pregnant anyway, would arise from yet another recognizable aspect of adoption worries, that the genetic inheritance might repeat itself.

As Alison Lurie illuminates, like many loved fairy tales “Rapunzel” encrypts the most disturbing and sensitive issues, which can’t be spoken of directly in front of the children.

Marina Warner

London, England

Alison Lurie replies:

Marina Warner’s comments on the French and Italian versions of “Rapunzel,” in which the herb the wife craves is parsley, known in folklore as a possible aid to ending a pregnancy, are—like all this brilliant scholar’s work—both interesting and original. If the story is read this way, it reverses the original motivation of the Grimm brothers’ tale, which begins “There was once an man and his wife, who had long wished for a child, but in vain.” It is possible, of course, that the text was altered deliberately. More likely, I think, the difference between the versions is another example of how folk tales continue to change their meanings over time and space, adapting to the tellers and their society.

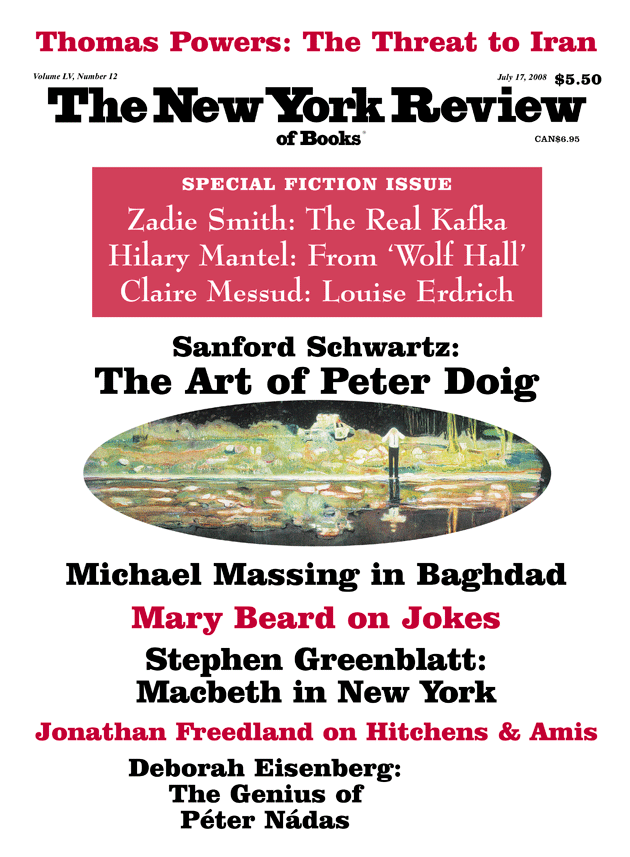

This Issue

July 17, 2008

His Royal Shyness: King Hussein and Israel