1.

Sometime during the mid-nineteenth century, writers discovered that traveling could be a lark. Disease might prevail in the tropics, but many of travel’s other hazards had disappeared: reliable marine engines protected ships against currents and capricious winds, railway companies built sanitary hotels, rooms could be booked by wire, banditry was on the wane, and there were far fewer postillions to be struck by lightning.

Nobody had more success with this idea than Jules Verne in his novel Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873, in which Phileas Fogg circumnavigates the globe at unprecedented speed to prove to his wagerers in the Reform Club that “the world has grown smaller.” Verne himself was not a great traveler—apart from a week in New York and a few European excursions he never left France—but he wrote the book at a desk facing the railway tracks at Amiens and the dreamlike promise of passing trains excited him, as it still excites strangers to the great European terminals who see expresses pull out with destinations such as “Praha” or “Brindisi” pasted to their windows. Fogg leaves London with very little luggage other than a copy of Bradshaw’s Continental Guide under his arm, as though that preeminent railway and steamboat timetable would be enough to see him safely across every sea, desert, swamp, and ravine.

The world’s first passenger railway opened in Britain in 1830. By the end of the century trains reached almost everywhere. No physical challenge seemed insurmountable. Lines looped up the Alps and the Himalayas and drove straight across the Florida Keys. Faced with unbridgeable water—the English Channel, the Kattegat, Lake Michigan—engineers devised ferries equipped with railway tracks so that whole trains could be shunted on board. There seemed no limit to the railways’ advance, the luxury of their trains, or the grandeur of their architecture. Trains brought British troops to the mouth of the Khyber Pass and hauled coal across the Arctic ice of Spitsbergen. In England, village stations charmed gentlefolk with flourishes of Gothic stone and Tudor brickwork; in America, majestic city terminals reminded the commuter of cathedrals.

And then the fever abated. Automobiles and aircraft broke the railways’ monopoly on land transport. The years of decline began in the 1920s, and though the decline was not universal (railways continued to expand in India and China), by the 1960s the passenger train was widely regarded as an outmoded means of travel other than for shuffling commuters in and out of cities. Nowhere was its fall steeper than in Britain and America, the countries that had once embraced railway travel more fervently than any other. The railway maps of both countries (but especially that of America) shrank from a dense summer thicket to the branches of a winter oak. New York’s Penn Station, a monument to neoclassicism spread over eight acres, was demolished in 1963 after only sixty years of useful life. Two years earlier, the wrecker’s hammers had broken down London’s Euston Arch, also Doric-columned and, with 1838 as the year of construction, the oldest great architecture of the railway age. Public opposition was fierce in both places—in Britain it reached the prime minister, Harold Macmillan—but the demolitions went ahead regardless. No matter its architecture, train travel was seen as a dying cause.

It was during the long Western slump in the fortunes of railways that a hard-pressed novelist, struggling to make ends meet by book reviewing, saw a literary opportunity. In 1972, when he was briefly writer in residence at the University of Virginia, Paul Theroux read Mark Twain’s Following the Equator (1897). As he explained to his then friend V.S. Naipaul (at least according to Theroux’s intermittently reliable memoir of their friendship, Sir Vidia’s Shadow1), Twain’s “obscure and out-of-print travel book” had give him the idea for a similar journey. Twain’s book appealed to Theroux because of its “geographical non sequiturs…incidental mishaps…spirited jokes.” Twain hadn’t pretended to be knowledgeable about the countries he passed through. “It was about nothing but his trip. A lot of it was dialogue.”

Theroux set off the next year on a journey that took him from London to Istanbul, and then onward to Tehran, Delhi, Madras, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, and Japan. He returned on the Trans-Siberian. In the industrial Indian city of Kanpur, he saw a street sign, “Railway Bazaar,” and remembered its potential. The Great Railway Bazaar was published in 1975 and became an immediate best-seller. It was Theroux’s tenth book and despite thirty books since it remains his most popular, the title most frequently associated with his name. After Bruce Chatwin published In Patagonia in 1977 critics began to talk of a renaissance in English travel writing, with Theroux and Chatwin leading the field.

Advertisement

Many other writers were inspired to follow a similar career—London publishers were eager for travel books—but Theroux’s influence was more than literary. The Great Railway Bazaar re-invested railway travel with the interest and romance of Twain’s day, replacing that age’s thrill of the modern with the appeal of the neglected and quaint. Soon British television was making series after series devoted to “great railway journeys”; a fashionable new travel company, Voyages Jules Verne, promised old-fashioned travel with none of its discomforts; a rich American, James Sherwood, refurbished the defunct Orient Express and set it running again (though only as far as Venice and not to Istanbul). Theroux himself reprised his success with further accounts of travel by train through Britain, South America, and China. Now, in Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, he revisits the scenes of his original great railway journey thirty-three years earlier, intending then-and-now comparisons, not least between his younger and older selves.

Theroux discloses that the jaunty tone of the first book was not true to his experience; rather its mood was confected as a therapeutic device. He was often lonely and miserable during his travels in 1973, in that different “age of aerogram letters and big black unreliable telephones” which made communication with his wife in London difficult and bred the suspicion that all wasn’t well. Sure enough, on his return he discovered that his wife had taken a lover.

Though unfaithful himself, he became “an angry brute” and threatened to kill both wife and lover in a fury that more than three decades later seems not to have completely ebbed: “…and as they belittle you [the absent Theroux] for having been an overindustrious drudge, they spend your money.” But he had a book to write, more money to earn, and he wrote himself out of his misery:

I made the book jolly, and like many jolly books it was written in an agony of suffering, with the regret that in taking the trip I had lost what I valued most: my children, my wife, my happy household.

In Verne’s novel, Phileas Fogg’s invaluable manservant, Passepartout, has no sooner joined the train at Charing Cross than he remembers—too late!—that he has left the gas burning in his master’s house. It may be the most celebrated instance of the neurosis that has haunted millions of travelers before and since; but Theroux’s are better reasons never to leave home.

2.

What is it about trains? Why do they seduce us? The Great Railway Bazaar has a fine opening sentence:

Ever since childhood, when I lived within earshot of the Boston and Maine, I have seldom heard a train go by and not wished I was on it.

Perhaps children who live under the flight paths of busy airports feel the same, but to a certain generation (the same or older than Theroux’s and this reviewer’s) no other transport can match the sight or sound of a train going by. The same thrill has run through almost every culture. A marvelous instance of it can be caught in Satyajit Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (1955), when the boy Apu and his sister Durga wander far from their Bengali village and unexpectedly see a train rushing through the fields, perhaps their first sight of the route to the world beyond, the route that in later films Apu takes. (Ray never forgets the railway motif and near the trilogy’s end the adult Apu gives his son a clockwork model of an engine.)

In England, E. Nesbit’s novel The Railway Children (1906) has been adapted for film and television so often that people now in early middle age, for whom steam locomotion is folk history, feel that they too in their childhoods heard a whistle moan and saw coal smoke drifting from a tunnel. When new, railways disturbed people as well as excited them. Dickens’s Mr. Dombey, traveling north from Euston in 1848, imagined that his speeding, clattering, shrieking train was following “the track of the remorseless monster, Death!”

By the twentieth century, they could no longer be characterized as noisy examples of the modern. The artists of the Futurist movement preferred airplanes and automobiles, and though the railways tried to catch up with fashion (there was an outbreak of aerodynamic design, or “streamlining,” in the 1930s), most writers and filmmakers saw trains as fond and familiar objects, a steamy site of romance that could provide a film’s setting or a novel’s plot device. Graham Greene, Agatha Christie, David Lean, Alfred Hitchcock: it would be hard to envisage their work without trains, and the probability is that the seeds of their enthusiasm were planted, like Theroux’s, in an early glimpse of hissing cylinders and childish dreams of escape.

Advertisement

In The Great Railway Bazaar, Theroux emphasized the attractions of the trains as things in themselves. He was, in his own word, jolly about them. Trains had bewitching whistles (in 1973 many were still powered by steam); they never upset your drink; they didn’t promote “the anxious sweats of doom” that air travel inspires. Like Verne and Hitchcock before him, he realized that “anything is possible on a train: a great meal, a binge, a visit from card players, an intrigue, a good night’s sleep, and strangers’ monologues framed like Russian short stories.”

In Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, Theroux advances a worthier reason for a writer to travel in them: what they reveal about the true state of the world. As Ford Madox Ford wrote, the view from the train window offers “so many little bits of uncompleted lives.” The train, says Theroux, “offers the truth of a place” by showing a country’s “dark, simple, and primitive” hinterland and the way many of its poorest people travel. On a Romanian train his spirits rise at the “filth and disorder” of the restaurant car. “It was easy to prettify a nation in an airport, but on this train…I felt I was seeing the real thing, a place with its pants down.” In India, rattling through some impoverished countryside, he thinks how much air travelers are missing—“the immensity, the destitution, the emptiness, the ageless solitude”—and how they would “know nothing of India.”

The world has changed so much since Theroux first made the trip. The tunnel from England to France has made the first stretch easier, but trouble in the Middle East makes Iran and Afghanistan impassable. Theroux starts to use car, bus, and plane as he makes the long detour north through former Soviet republics. On the one hand, he meets very few people there (or elsewhere) who have a good word to say about George Bush and his foreign policy—in a trip of 28,000 miles and hundreds of encounters he finds only two Bush supporters—but on the other hand, very many people want to migrate to America. In Georgia,

there was hardly any distinction, and not much romance, in being a traveler. It was now a world of travelers, or people dreaming of life elsewhere—far away. Please, take me to America!

As “traveler” is just a notch down from “writer” in Theroux’s description of himself, this is a depressing truth: to be one among so many. New technologies, the Soviet collapse, the galloping prosperity of Asia, the confidence of the West’s moneyed young: they have set loose many millions of tourists as well as migrants, and the difference between “tourist” and “traveler” is, after all, mainly a subjective conjugation; I am the traveler, you are the tourist. Theroux offers an interesting glimpse into his character when he extols travel because “in a distant place no one knows you—nearly always a plus.” It allows you “to pretend…to be different from the person you are, unattached, enigmatic, younger, richer or poorer.”

In 1973, he was often a solitary impostor. Now they are everywhere, and he himself is partly to blame. In Laos, he discovers that backpackers have replaced the whores and their stoned GI clients on leave from the Vietnam War. One backpacker is a thirty-year-old Englishwoman and “like a lot of solitary travelers, resourceful, also shrewd, direct, opinionated and full of misinformation.” In an otherwise inconsequential conversation, of which the book has many, Theroux asks her if traveling is all she wants to do:

She said, “Yes. My hero is Michael Palin. The BBC guy? He goes all over the world.”

I said, “With a camera crew and someone to do his makeup and buy his tickets. He’s got people to tell him where to stand!”…

“That’s what I want to do.”

“Be Michael Palin? That’s your ambition?”

“Wouldn’t you want to be Michael Palin?” she asked.

Palin’s BBC programs and their spin-off books have become enormously successful in Britain, depending for their success on the likability and wry curiosity of the presenter (a former member of the Monty Python team) and the comedy of his encounters with people and places remote to his large audience. At least in Britain, the travel narrative is far from dead. Television series (Palin’s is only the most prominent of many) and comic writers such as Bill Bryson have made it a part of popular culture, and it is much harder to suggest (as Theroux does by referring to his new and faithful wife as Penelope) that the traveler is a modern Odysseus, which was still just possible in certain parts of the world in 1973. Now Penelope calls up Odysseus on his cell phone.

Theroux seems rather disenchanted with the kind of personality his first book did so much to encourage. The traveler’s worst nightmare, he writes, isn’t the secret police or malaria “but rather the prospect of meeting another traveler.” As to travel writers, Theroux is equally fierce:

Most writing about travel takes the form of jumping to conclusions, and so most travel books are superfluous, the thinnest, most transparent monologuing. Little better than a licence to bore, travel writing is the lowest form of literary self- indulgence: dishonest complaining, creative mendacity, pointless heroics, and chronic posturing, much of it distorted with Munchausen syndrome.

Personal confession or self-exempting criticism of the genre at large? As a writer, Theroux is light on his feet. He says this passage reflects a mood that came on him when he was packing to leave home, but to this reviewer his words seem near the mark. What good are these books that dash across the world, what can they tell us, what are they for? The Web these days offers a multitude of foreign perspectives, if we can be bothered to sit at our laptops and tap. In books, writers and scholars devote their lives to single nations, single events, and sometimes single cities. A good study of modern Mumbai such as Suketu Mehta’s will tell us more about India than any account drawn from six months in the country.2 V.S. Naipaul’s travel writing, if his nonfiction can be so described, comes out of a long and very personal engagement with the Caribbean and South Asia, while a globe-trotting polemicist such as Thomas Friedman at least offers an economic argument.

Ghost Train to the Eastern Star is too long—a third as long again as the book of the original journey—and sometimes slackly written. “Speaking of time warps, Hungary was about to elect another socialist government” is not a good sentence grammatically, while “Pale, pop-eyed Romanians had a touch of Asia in their dark eyes and hungry faces” is a dubious one for all kinds of other reasons. That old trick, foreigners speaking English comically, gets full play. There are nice images (“dented tureens of mulligatawny” exactly captures a certain kind of subcontinental dining room) and aggressive descriptions. Of Bangalore, he writes:

What went under the name of business [there] was really a form of buccaneering, all the pirates wearing dark suits and carrying cell phones instead of cutlasses. The place had not evolved; it had been crudely transformed.

Sometimes he writes no more than bad journalism (a Singapore brothel has “numbered beauties”) and at other times he might be a backpacker filing a blog (in Cambodia, he gets “a creepy feeling that I put down to bad vibes.”). When he reaches Turkmenistan, then under the dictatorship of the late Saparmyrat Niyazov, any care with words disappears altogether. Niyazov, who died in 2006, was a despot who banned beards, gold teeth, and ballet. In the space of a few pages, “one of the wealthiest and most powerful lunatics on earth” rules a country that Theroux thinks of as “Loonistan”—“uniquely weird,” “a gigantic madhouse run by the maddest patient.” Niyazov’s schemes are “insane,” though some are “nuttier” than others. Lest we forget, he is “out of his mind.”

Aphorisms appeal to Theroux. “Two of the most appalling words a newly arriving traveler can hear are ‘national holiday'” is an amusing one, though others (“Luxury is the enemy of observation…”) are less convincing. He isn’t afraid to generalize. He flees a provincial Chinese town and its Louis Vuitton store after a day or two, reveling in the thought that he need never see China again, despising the entire population’s enthrallment to money. What sends him away from India is “the sheer mass of people…. India was a reminder to me of what was in store for us all…the contending billions, like those ants on the rotting fruit.”

And yet he likes India. The English language and Indian civility allow his brass-necked inquisitiveness full rein. He writes:

No one can travel among the American poor the way I could travel among the Indian poor, asking intrusive questions. What’s your name?… How much money do you make?

This fact—true by my experience—indicates the weaknesses of travel writing as we’ve come to understand it, and how many of its tropes and attitudes derive from a world more easily divided by continent into rich and poor. Theroux thinks there is “a depressing travel book” to be written about America’s poor:

The poor in America live in dangerous places…. I have never seen any community in India so hopeless or, in its way, so hermetic in its poverty, so blatant in its look of menace, so sad and unwelcoming, as East St. Louis, Illinois….

The problem for Theroux is: how can a writer penetrate this world in Illinois? It would be too difficult and dangerous for anyone simply passing through. To be safe enough and to understand enough, the writer would need to be part of life there. These are Theroux’s home thoughts from abroad and they suggest, though it isn’t clear he’s aware of it, that the bell is tolling for the long tradition of a literary form founded on the unspoken idea that stability and normality are to be found where you started from, that everywhere else is a little crazy.

Perhaps the most affecting episode of his journey comes in Burma (Myanmar), where the military dictatorship (an army so huge it resembles a “parallel population—healthier, better dressed, better educated”) has preserved the country much as it was. He takes the little train to the old British hill station of Maymyo, still with its pony carts and bungalows, and stays at the quaint hotel he last visited thirty-three years before. The old Indian owner, affectionately portrayed in The Great Railway Bazaar, is dead, but his son remembers Theroux and makes a fuss of him because his book has brought the hotel attention and customers. At last the author has found “a witness to my long-ago misery, my loneliness, my scribbling.” The son invites him home to tea:

They showed me family albums….And so I sat there, and drank tea, and was happy…. Nothing like this had ever happened to me among my own family. Was this a motivation, the embrace of strangers, in my becoming a traveler?

From the evidence of Theroux’s other work—this is his forty-first book—the answer would surely be yes. Elsewhere in this account, he insists that he will never write an autobiography; and perhaps there really is no need. In fiction and nonfiction, he has documented most of his life: his mild and likable father who never read a book he wrote, his enduring hatred for his mother, the surrender to the call of the Boston and Maine, his escape to the Peace Corps and a life far away filled with sexual escapade.

The problem for the later biographer will be separating the invention in his nonfiction and the fact in his fiction, two categories of the literary form that Theroux has always chosen (in that excusing word) to “subvert.” Sometimes, the invention being so brazen, he has easily been found out: his claim to have met Naipaul’s second wife as a young girl in Africa is the most fantastical example. But now in Burma comes a confession about the Maymyo hotel’s old owner:

Though I had claimed in The Great Railway Bazaar to have encountered him on the train—I wanted to give my little trip some drama—it was here at [the hotel] that I’d first met the hospitable Mr. Bernard.

A small thing—though less so when you turn to that book and see what the deceit has required. Travel writing of a certain kind—perhaps the novelist’s kind—seems to demand it.

3.

Home after 28,000 miles, Theroux lists his conclusions:

Most people on earth are poor. Most places are blighted and nothing will stop the blight getting worse…. There are too many people, and an enormous number of them spend their hungry days thinking about America. Most of the world is worsening, shrinking to a ball of bungled desolation.

It may be so, and there is little point in wishing for a more elegantly expressed prognosis if it is. The state of the world as Theroux finds it, however, is a less interesting project than the state of Theroux as he finds himself. “Only the old can really see how gracelessly the world is aging and all that we have lost,” he writes on the last page of a book that is as much about getting old as getting places. As a man in his mid-sixties, he lacks the zip of his thirty-two-year-old self, but he is probably more humane and more generous. He gives to charities. In Burma, he befriends a rickshaw pedaller of the same age (“Like me, he too was a ghost—invisible, aging, just looking on, a kind of helpless haunter”) and as he leaves hands over to him “a fat envelope of dollars.” Seeing a disheveled old white man at a border crossing in Malaysia, he feels “protective, and fearful too. In a matter of years that wandering coot, the ghost whom no one noticed, would be me.”

This fear of advancing invisibility also plays its unintended part in Theroux’s conversations with the writers he meets along the way, in which, one way or another (their shared tastes in authors or pens), Theroux seems anxious to establish that he is a writer just like them, and just as good as they are. It is hard to know what other purpose such a faithful record of banality could serve. In Istanbul, he sees himself in the Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk: “I felt he physically resembled me, and he had my oblique habit of affecting to be ignorant and a bit gauche in order to elicit information.” In Kyoto, he meets the unlucky Pico Iyer, who after several famous names have been hit back and forth across the net (V.S. Naipaul, Jonathan Raban, Jan Morris) eventually asks:

“What about S.J. Perelman—do you like his work?”

I said, “Very funny stuff. I like it a lot. I knew him in London.”

“I wish I’d met him…. Friendly?”

“Very. And a natty dresser. Something of a womanizer. Well read. Widely traveled….”

There are many brighter moments, but the underlying note, the book’s fretful clickety-clack, is the same sound that Mr. Dombey heard on his trip down the world’s first main line:

Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, from the town, burrowing among the dwellings of men and making the streets hum, flashing out into the meadows for a moment…through the corn, through the hay, through the chalk, through the mould…among objects close at hand and almost in the grasp, ever flying from the traveller, and a deceitful distance ever moving slowly within him: like as in the track of the remorseless monster, Death!

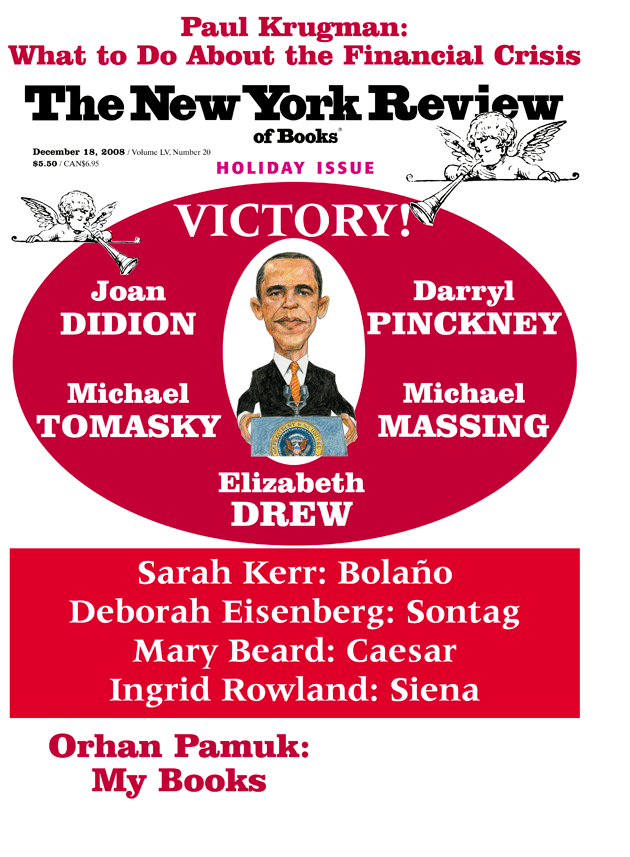

This Issue

December 18, 2008

-

1

Sir Vidia’s Shadow: A Friendship Across Five Continents (Houghton Mifflin, 1998). ↩

-

2

Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found (Knopf, 2004); reviewed in these pages by Pankaj Mishra, November 18, 2004. ↩