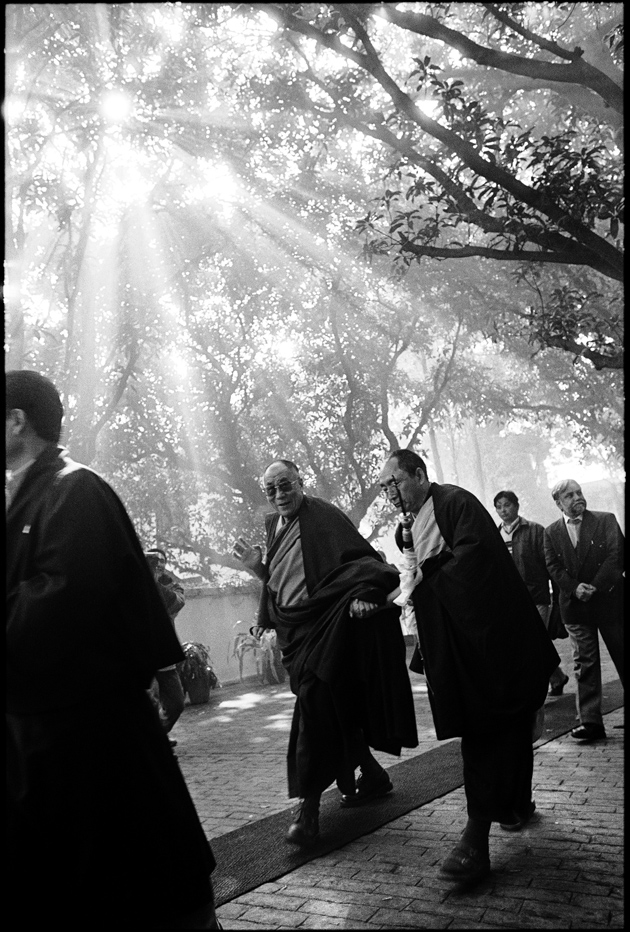

“The situation inside Tibet is almost like a military occupation,” I heard the Dalai Lama tell an interviewer last November, when I spent a week traveling with him across Japan. “Everywhere. Everywhere, fear, terror. I cannot remain indifferent.” Just moments before, with equal directness and urgency, he had said, “I have to accept failure. In terms of the Chinese government becoming more lenient [in Chinese-occupied Tibet], my policy has failed. We have to accept reality.”

Accepting reality—first investigating it clearly, and then seeing what can be done with it—is for him a central principle, and now he was about to convene a meeting of Tibetans in his exile home, in Dharamsala, India, and then another, in Delhi, of foreign supporters of Tibet, to discuss alternative approaches to relieving the ever more brutal fifty-year-long suppression of Tibet by Beijing. “This ancient nation with its own unique cultural heritage is dying,” he said later the same day. “The situation inside Tibet is almost something like a death sentence.”

It was shocking to hear such words from a man who has become one of the modern globe’s foremost embodiments of patience and the power of never giving up. I had spent a week with him traveling across Japan the previous November—and the one before that—and even then he had been working hard to find common ground with China, though he was never slow to speak out against corruption, censorship, and oppression in the People’s Republic. In the thirty-four years I’ve been regularly talking and listening to him, I’ve grown used to seeing him begin each day by praying for his “Chinese brothers and sisters,” and constantly asking his fellow Tibetans “to reach out to the Chinese people and make better relations.” He was still doing all that this winter and yet there was a sense, for the first time that I had seen, that he could no longer contain his impatience and disappointment with Beijing, and was determined to speak out now, telling the world what he knew, while also urging his people to prepare for the time when their leader for sixty-nine years, who is now seventy-three years old, would no longer be among them.

The year just past was something of an annus horribilis for the Tibetan leader and his people: last March, on the forty-ninth anniversary of his flight into India, demonstrations spread across Tibet and led to a Chinese crackdown that is bringing about more deaths and imprisonments than we will ever likely know about. In August, the Dalai Lama was forced to cut short a trip to France for reasons of ill health. One week later, his eldest brother, Taktser Rinpoche, himself an incarnate lama, died in Indiana, where he had been based for several decades. Five weeks after that, the Dalai Lama had gallbladder surgery, a procedure that usually takes fifteen or twenty minutes, he said, but in his case took three hours. And just after he returned from Japan on his first major trip since his illness, clearly ready to talk to Beijing in a new way, China terminated its regular meetings with his envoys, essentially accusing him of arguing for ethnic cleansing. It could seem as if the Chinese had begun the talks in 2002, months after being named host of the 2008 Summer Olympics, in order to appease a watching world; now that the games had been successfully completed, they could bring to an end even the pretense of talking to Tibet.

As I watched and listened to him speak, day after day, behind closed doors, to groups of Chinese individuals, to members of the international press, and to Japanese power brokers, I could not help feeling that the Dalai Lama was newly determined to hold nothing back. The same spirit was evident when he said, on this year’s March 10 anniversary—the fiftieth—of what Tibetans call the “Tibetan Uprising,” when 30,000 Tibetans in Lhasa took up arms to protect the twenty-three-year-old Dalai Lama, allowing him to flee in safety from Tibet (in China it is being celebrated as “Serf Liberation Day”), that the Beijing government had turned Tibet into “a hell on earth.” Already, tensions have intensified across China and Tibet because of the anniversary, and China recently launched a forty-two-day “Strike Hard” policy involving arrests of dozens of Tibetans who have refused to celebrate the Tibetan New Year (out of respect for those who died last March). Beijing has worked long and hard to make sure that no one in the outside world sees what is happening inside Tibet. But in this case, when a body falls in a forest, all of us know that it is falling, even if we do not witness it firsthand.

Advertisement

The first thing the Dalai Lama said to me when I met him on the opening day of his recent tour, in his Tokyo hotel, was, “My surgery was very successful!” He had visibly lost a lot of weight in the three months since I’d seen him last, but his recovery from the gallbladder operation had been unusually fast, he told me, and his doctors had said that his body was that of a man in his sixties. Certainly, anyone who saw him opening his arms to the Chinese intellectuals eager to have a photo with him, receiving Mongolians gathered to present ceremonial blue scarves to him in the lobby of his hotel, talking to Japanese politicians in his suite, and just making sure that he shook hands and conversed with every last waiter, bodyguard, and interested passerby would have felt she was seeing the affectionate, mischievous, and attentive man the world knows. Every time he began speaking about the situation in Tibet, though—and on this tour, as not before, the questions even from Buddhist monks were political—he spoke with the unwavering clarity and passion of a man whose charges are trapped in a burning house.

You can see something of how the Tibetan leader works in the world by simply noticing how he allocates his time on such a trip: he delivered two major talks to the general public, on his favored theme of “secular ethics”—the logical basis for thinking of others, whether or not you have a religion; he flew down to the southern island of Kyushu to offer Buddhist teachings to a group of four hundred or so (often feuding) Japanese Buddhists who had invited him to their country for that purpose; he even spent an entire morning visiting a girls’ school in the provincial capital of Fukuoka, since his first priority is always education, and helping those young enough to be in a position to shape the future.

Yet the first day of his trip was dedicated to talking to Chinese residents in Japan: two and a half hours in the morning with a group of fourteen professors, and three hours in the afternoon with a boisterous, animated crowd of two hundred or so students and others. And much of the next two days was spent speaking to the Japanese and international press and television about how things stand in Tibet today, and urging them to try to go themselves and offer an “independent, objective, unbiased investigation” into what is really happening behind the black curtain China has yanked down.

Whenever he was asked, he did not hesitate to tell his listeners about a new Chinese policy of beating Tibetans as soon as they are arrested; about the eighty-year-old Tibetan man who had asked why monks should be arrested for calling for basic human rights, and who was himself imprisoned and subjected to beating; about reports of Chinese trucks in Tibet last March packed with dead bodies being taken away to be buried. He had not had the chance to “independently cross-check” every report, he took care to stress, so they should not all be taken as proven fact; but other reports have suggested that at least 140 Tibetans were killed last March alone, and more than nine hundred have been taken into custody, often after having been beaten.

After the demonstrations last March spread with unprecedented speed and intensity across the Tibetan Autonomous Region and China proper, Tibetan hopes had been raised when Chinese President Hu Jintao called for a special meeting, for the first time acknowledging in public that the Chinese were holding talks with delegates from the Dalai Lama. Several world leaders were speaking then of boycotting the opening ceremonies of the Olympics in August and much of the world was looking to China to show some sign of good faith and loosening oppression in the months leading up to the games. The Dalai Lama never supported a boycott, and appealed to Tibetans not to disrupt the carrying of the Olympic torch around the world. He had reason, he said, to hope that the Chinese government might budge a little.

But when the two sides met for their seventh round of talks, in July, he told the Chinese professors in Tokyo, “There was nothing new from the Chinese side. It was the usual allegations against us.”

I happened to see the Dalai Lama later that month, at the Aspen Institute, and there he startled many of us by saying, for the first time that anyone could remember, “My trust in the Chinese leadership is this thin now” (he held his fingers a tenth of a centimeter apart). “I really don’t know what I can do.” In the meantime, as he often freely acknowledged in Japan, his “Middle Way” policy—of not seeking full independence from China for Tibet, but only a “genuine and meaningful autonomy,” whereby China could control Tibet’s defense policy and foreign affairs, while Tibetans might enjoy the freedom to take care of their culture, their religion, and their special environment—was coming under more and more criticism. So, he said, he would step aside and allow others to come up with a “new, wiser, realistic” approach.

Advertisement

He might almost, with his candor and frank self-criticism, have been reminding the Chinese of what they lack. Democracy has always been a particular passion of this Dalai Lama, as both one of the secular practices of the wider world that Tibetans can now usefully learn from and an idea perfectly consonant with the Buddha’s own belief that all beings are equal, and each person should rule himself. Within his first year in exile, in India, he was beginning to draft a constitution for Tibetans to allow them democracy for the first time in their history (and to allow for the impeachment of the Dalai Lama). In the years since, he has systematically extended the possibility from a democratically elected parliament to a democratically elected cabinet to, in 2001, a democratically elected prime minister in exile (currently the scholarly monk Professor Samdhong Rinpoche). Even as the king of Bhutan, educated by some of the same Buddhist teachers as the Dalai Lama, more or less imposed democracy on his reluctant people last year, and Nepal next door edges a little away from monarchy, the Dalai Lama continues to hope, sometimes in vain, that his people will take responsibility themselves for shaping their own futures.

It is not always easy to appreciate from afar how radical this Dalai Lama is in dispensing with any tradition he feels to be outdated (he is sometimes more radical, as well as more open to other views, than the conservatives in his own community would like). “The Dalai Lama institution came about around six hundred years ago,” he told the Chinese students in Japan, “and for more than three hundred years the Dalai Lama has been spiritual and temporal head of the Tibetan people. But that time is gone.” A Dalai Lama might no longer be useful, he seemed to be implying, especially since, upon his death, China will likely produce a young boy of its own and pronounce him Dalai Lama. New times require new solutions. It now seems more than possible that the Dalai Lama will in some way, explicit or otherwise, designate his own successor from among the young lamas around him and ask Tibetans to treat him as their leader, whether or not he bears the name of “Dalai Lama.” Tibet no longer has the luxury of being able to look for a young child and then wait another fifteen years for him to come of age.

Still, I’ve always noticed that his pauses are longest whenever I ask him about how to persuade his people to break their centuries-old habit of deferring to the Dalai Lama in everything. His government-in-exile can look after the 2 percent of Tibetans who live outside Tibet, and this March, in place of the teachings he usually offers to the public outside his home, in accordance with classic Tibetan custom, he is personally ordaining one thousand new Tibetan Buddhist monks in southern India. But as he told me four years ago, “When I go, I don’t know. All depends on the respect of the Tibetan people for their popularly elected leader. One hundred percent popular, impossible! But 60, 70 percent, and still 30, 40 percent, opposed: it can create some problems.”

As most observers note, it is in China’s interests to try to resolve the Tibetan situation now, if only because no other Tibetan is likely to be as forbearing or as open as the current Dalai Lama, let alone as intimately acquainted with the leadership and entire history of the People’s Republic.

Throughout his week in Japan—and even as he reiterated that this is the “darkest period in Tibetan history”—the Dalai Lama took pains to stress, over and over, his “great faith in the Chinese people,” and his eagerness to spend an entire day just talking to regular Chinese gave proof of that. “The Han Chinese are a hardworking people,” he told the Chinese professors. “Wherever they settle, they have Chinatowns; they have their own culture; they keep intact.” What, in other words, was the government in Beijing afraid of? Did it think that loosening up on Tibetan culture and religion would somehow erode the strength and integrity of a proud Han culture going back millennia?

“China’s ambition to have a superpower,” the Tibetan leader told some TV interviewers, as he sat calmly within a circle of cameras, “is right! Theirs is a most important nation, an ancient nation.” Tibetans themselves stood to gain from these developments. “Every Tibetan,” the Dalai Lama said, as he often does, “is in favor of modernization.” None wishes to go back to the seclusion and backwardness of old. Yet to be a superpower brings with it certain obligations, having to do with democracy, rule of law, and freedom of the press. “Manpower, military power, monetary power, that is already there in China,” he said. “But moral power, moral authority is lacking.”

Over the decades I’ve known him, the Dalai Lama has always been adept at pointing out, logically, how Tibet’s interests and China’s converge—bringing geopolitics and Buddhist principles together, in effect—and at arguing, syllogistically, for how the very notion of enmity is not only a projection, nearly always, but, in today’s globally interconnected world, an anachronism. But now, with the skill of one trained for decades in dialectics and personally familiar with the last few generations of Chinese history, he seems more and more to be holding the Chinese government up against its own principles. “Chairman Mao, when I was in Peking, said, ‘The Communist Party must welcome criticism. Self-criticism as well as criticism from others,'” he noted pointedly in Tokyo. But now the Party seemed to be all mouth and no ears. Deng Xiaoping, he reminded another audience, always stressed “seeking truth from facts,” the very empiricism the Dalai Lama would love to see more thoroughly deployed. “When President Hu Jintao talks of a ‘Harmonious Society,’ I am a comrade of his,” he told the Chinese scholars. “Even today I have points of agreement with Marxist thought.”

His argument, unexpectedly, was that Communists in China today are not Communist enough, as they ignore Marx’s ideas of ethics and equality (which the Dalai Lama has long admired) and move ever further from the purity and self-sacrifice of their early years. “Mao Zedong was a true idealist, a real comrade, initially,” he told the Chinese students. “But in ’56, ’57, that disappeared.” The result, he said, was that “the Communist Party in China today is something very special; it is a Communist Party without Communist ideology.” At one point, he even said to his Chinese listeners, “Maybe in some ways I’m more ‘red’ inside than the Chinese leadership!”

In recent months, the Dalai Lama seems to be returning more and more to the extended meetings he held with Mao and other Chinese leaders when he spent several months in Beijing and traveled around China in 1954 and 1955, so impressed by much of what he saw that “I actually said that I wanted to join the Communist Party” (as he told the Chinese intellectuals). He remembered Mao treating him almost as a son, feeding him with his own chopsticks, and in 1955 a time when “Mao looked at me and said, ‘Tibet in its past history has been a powerful nation. But now it is weak. We are keen to help you. After twenty years, Tibet will be a powerful, great nation. It will be your turn to help us.'” Especially when Chinese are around, he recalls Mao pointing to two generals and telling the Dalai Lama, “I sent these two to Tibet in order to help you. If they are not doing well, or acting according to your wishes, then let me know, and I will drop it.”

“Past history is past history,” he acknowledged more than once in Japan. Yet by giving his own firsthand account of what he remembers, more and more, and by stressing his admiration for what those on the Long March and Mao in his early years achieved, he seemed to be asking the current leadership in Beijing what would sustain its people beneath their thoughts of money and control. In the course of his sixty-nine years in power, the Dalai Lama has seen one country after another—in the West and more recently in places like Japan and Taiwan—gain prosperity and modern institutions and then come to him asking what to do with their sense of emptiness, their broken families. At some point, he suggested, China is going to have to find something to support it at some level deeper than just growth rates.

It is common, especially in recent months, to hear people asserting that the Dalai Lama is a wise and even heroic spiritual leader who is nonetheless a little out of his depth in the cut-and-thrust of realpolitik, which observes rules and priorities very different from the monastic ones. And indeed, to the surprise of many, he has long maintained that Tibet should, in the future, separate church and state, one reason why, were he to return to Tibet, he would not seek any political position. Yet listening to him in Japan—and in India, America, and Europe in recent years—I’ve been struck by how much more practical and concrete his proposals sound than those of the Chinese leaders or of the Tibetans around him.

Tibetans are outnumbered by Han Chinese by more than two hundred to one, so any act of violence toward the Chinese will bring only more suffering on those Tibetans in Tibet who have suffered too much already (and, for that matter, on many Han Chinese). Nor has Beijing ever shown itself very responsive to provocation from abroad or to direct challenges to its authority. The one reason why Tibet has won the support of most of the world is that it has so far refused the path of violence; a single terrorist attack on Chinese roads or power stations might win the headlines of the world press for a few days and then squander the world’s goodwill forever. In any case, the Dalai Lama and his fellow exiles are in India as spiritual refugees. If they were to engage in political mischief from there, they would not only enrage China and imperil their fellow Tibetans, but also put their hosts in a difficult position, and even perhaps precipitate a confrontation between the two great Asian powers.

The fact that the Dalai Lama’s policy has reaped no evident fruits so far, however, only makes more and more of those concerned about Tibet desperate for another approach; given the odds against them, many feel that they might as well ask for the impossible (even the Dalai Lama’s eldest brother was an outspoken advocate of independence, and not the Dalai Lama’s conciliatory call for “autonomy”). Yet when the meetings to chart a new policy took place in India in November, the Dalai Lama remained completely absent so that no Tibetan would try to follow him—and again the Tibetans decided to follow the Dalai Lama’s course.

This leads to the difficult position of Tibetans following the way of peace even as many of them hunger for something more decisive. Many in the Tibetan community and abroad, centered around the Tibetan Youth Congress, call for nothing less than full independence. “But I always ask them,” the Dalai Lama said, “How are you going to attain independence? Where are you going to get the weapons? How are you going to pay for them? How are you going to send them into Tibet? They have no answer.”

Meanwhile, though 98 percent of all Tibetans—those inside Tibet itself—have essentially been silenced through Chinese control, discreet inquiries from their cousins in Dharamsala suggest that they are at once entirely behind their exiled leader; yet they find it hard to hold on to their patience (as they watch their neighbors imprisoned or tortured, and monks and nuns arrested if they do not denounce their spiritual leader). Traveling regularly to Tibet since 1985, I have been surprised to see Tibetans growing ever more strongly committed to the Dalai Lama and their distinctive heritage—even as Lhasa and other parts of their country are turned into generic Chinese versions of Las Vegas—precisely because they are being stripped of external ways of defining themselves. Their leader and their culture and their religion are the only ways they can remind themselves that they are Tibetans, and not just Chinese citizens with an exotic background.

The stakes in Tibet right now could not be higher, even for those of us who live very far away from Asia. In China, Tibet is sometimes referred to as the “Third Pole,” an indication of how much its huge quantities of ice and snow, almost as great as those of the North Pole, are subject to the ravages of global warming. Americans and Australians and French people may have taken up Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama told an overflow crowd of three hundred crammed into a twentieth-floor breakfast room in Tokyo’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club, but without Tibetan practitioners for at least a generation or two more, Tibetan Buddhism might not survive. Tibetans are glad and grateful for all the modern facilities and material opportunities that Beijing has brought them, he constantly stressed, but that did not mean they felt they should give up their distinctive cultural tradition and basic freedoms of speech and religion in return.

As Tibet enters its second half- century as an oppressed nation—this fall marks the sixtieth anniversary of the arrival of People’s Liberation Army troops in eastern Tibet—there is a sense that what happens there has implications for us all, not just in its environmental consequences, but in its political ones as well. How China deals with Tibet will affect its relations with Taiwan, and if Beijing does come to its senses and takes a more enlightened and farsighted approach to Tibet —as small a threat to it, population-wise, as Idaho might be to the US—it will inevitably win the respect of the larger world and do much to secure its own legacy. Part of the unusual fascination of the China–Tibet issue, after all, is that it seems to suggest a larger question beyond the geopolitical: How much can anyone live on bread alone, and to what extent does some sense of inner wealth either trump or at least make sense of all the material riches we might gain? It’s no surprise, perhaps, that 100,000 Han Chinese have already taken up the study of Tibetan Buddhism, and their numbers are rising quickly.

The Dalai Lama has done his bit by announcing himself “semi-retired,” something like a “senior adviser,” in his own words; if Beijing thinks he is the cause of the recent disturbances and problems in Tibet, he has been effectively saying, he will gladly take himself out of the equation altogether to see if that can help. The Tibetans in Tibet have endured a lifetime of oppression with uncommon patience and fortitude. Now it remains only for China to be as “realistic” and transparent in its handling of Tibet as, the Dalai Lama noted, it was in the wake of the tragic earthquake in Sichuan last summer. His final words to the Chinese students, some of whom were sobbing and working Tibetan Buddhist rosaries as he spoke, were “Investigate, investigate. Analyze, analyze.” He left the Chinese professors with the words, “Keep out the propaganda. Keep out our Tibetan side, too, our emotions. Study the situation!” Two days later, however, as he was addressing the journalists in Tokyo’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club, another Tibetan man was imprisoned, for five years, according to Human Rights Watch. His crime? Daring to tell relatives abroad about what is happening inside Tibet.

—March 12, 2009

This Issue

April 9, 2009