Facebook, the most popular social networking Web site in the world, was founded in a Harvard dorm room in the winter of 2004. Like Microsoft, that other famous technology company started by a Harvard dropout, Facebook was not particularly original. A quarter-century earlier, Bill Gates, asked by IBM to provide the basic programming for its new personal computer, simply bought a program from another company and renamed it. Mark Zuckerberg, the primary founder of Facebook, who dropped out of college six months after starting the site, took most of his ideas from existing social networks such as Friendster and MySpace. But while Microsoft could as easily have originated at MIT or Caltech, it was no accident that Facebook came from Harvard.

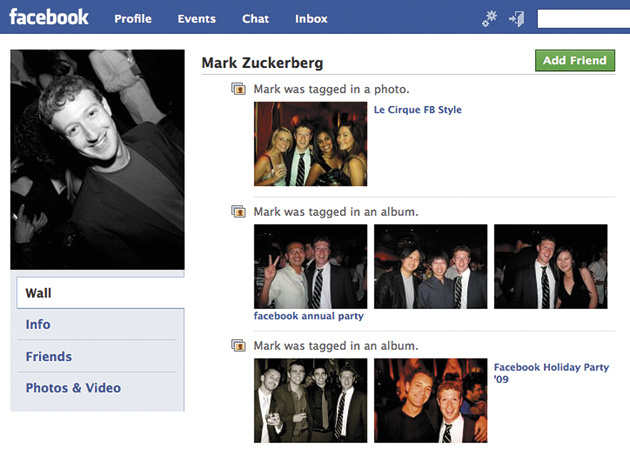

What is “social networking”? For all the vagueness of the term, which now seems to encompass everything we do with other people online, it is usually associated with three basic activities: the creation of a personal Web page, or “profile,” that will serve as a surrogate home for the self; a trip to a kind of virtual agora, where, along with amusedly studying passersby, you can take a stroll through the ghost town of acquaintanceships past, looking up every person who’s crossed your path and whose name you can remember; and finally, a chance to remove the digital barrier and reveal yourself to the unsuspecting subjects of your gaze by, as we have learned to put it with the Internet’s peculiar eagerness for deforming our language, “friending” them, i.e., requesting that you be connected online in some way.

Facebook was successful early on because it didn’t depart significantly from how its audience interacted, and because it started at the top of the social hierarchy. Zuckerberg distinguished his site through one innovation: Facebook, initially at least, would be limited to Harvard. The site thus extended one of the primary conceits of education at an elite university: that everyone on campus is, if not a friend, then a potential friend, one already vetted by the authorities. Most previous social networks, such as MySpace and Friendster, had been dogged by the sense that, while one might use them with friends, they were to a substantial degree designed for meeting strangers. But nobody is a stranger in college, or at least that’s the assumption at a school like Harvard, so nobody would be a stranger on Facebook.

The site’s connection to collegiate social codes could be seen most clearly in its name, which, unlike that of every previous social network—Friendster and MySpace, but also SixDegrees, Bebo, Orkut, etc.—actually came from a preexisting, even highly traditional item, the freshman “facebook” that many colleges distribute to incoming students, with a photo of each classmate and a few identifying details. Zuckerberg’s Web site would retain the exclusivity of its namesake through one requirement: to join, you would need a Harvard e-mail address.

By starting at Harvard, Facebook avoided another problem that had afflicted previous social networks: those with many friends had little reason to sign up. Zuckerberg got the initial idea from two members of the Porcellian, Harvard’s most prestigious “final club,” who would later sue him for stealing their plan (the case was settled out of court for a reported $85 million). The importance of the site’s Ivy League founding is the primary revelation of Ben Mezrich’s dramatic, narrative account of Facebook’s early days, The Accidental Billionaires. When Zuckerberg launched the site, as Mezrich observes in one of the book’s more accurate moments, he e-mailed the announcement to the Phoenix, a final club. A month later, the site expanded to Princeton and Stanford. Facebook, unlike every previous social network, was at the start a very exclusive club.

If a social network profile was an online “home,” then a Facebook page, in the early days, looked like a room in a recently constructed dorm: you might put up a raunchy poster or fill the shelves with favorite books, but the layout and the furniture remained exactly the same for everyone. One acquired this home in much the same way one acquired a freshman roommate—by sending a picture and filling out a form. Here are a few details you were asked to provide:

Name, Gender, Birthdate, Academic Major, Residence Hall, College Mailbox, High School; Email, Phone Number, Current Address; Political Views, Collegiate Activities, Interests; Favorite Music, Favorite TV Shows, Favorite Movies, Favorite Books, Favorite Quotations.

Not a few budding sociology majors must have been reminded of the work of Pierre Bourdieu, the French scholar best known for using surveys of social class and preferred artworks to argue that aesthetics is largely a matter of social distinction and “position taking.” But Zuckerberg was less interested in sociology than sex, as the most prominent questions on the form showed. These were multiple choice:

Advertisement

Interested In: Men; Women. [You could always choose both.]

Looking For: Friendship; A Relationship; Dating; “Random Play”; “Whatever I Can Get.” [Or all five!]

Relationship Status: Single; In a Relationship; Engaged; Married; “It’s Complicated”; “In an Open Relationship.” [A list Zuckerberg considered expansive enough that he made members pick just one.]

Finally, if you hadn’t managed to convey the complete essence of yourself with the above, you could type something insightful “About Me.”

The way students responded to these queries was often amusing: many listed themselves as “married” to their best friends or roommates; some who were in long-term relationships claimed to be interested only in “Random Play.” Instead of photos of themselves, early members often chose works of art or album covers or portraits of writers; those who included a personal picture rarely chose the most attractive, attempting, through a drunken photo or a candid shot, to convey an attitude of nonchalance. The list of “Favorites” was the occasion for particular anxiety and comedic juxtaposition, as Beethoven might share space with contemporary pop groups like OutKast or, more ironically, commercial schlock like Celine Dion.

The site was a lark. For all that it reduced personality to a series of “position takings” and changed the word “friend” from a noun, something defined by duration, to a verb—“I friended him,” a one-off event—the early Facebook nonetheless appeared as a natural extension of the atmosphere of college, where everlasting friendship often seems as simple as making another late-night dorm-room acquaintance, and whether one names Jane Austen among one’s favorite authors, or removes Charlotte Brontë from the list, can seem enormously important, deeply representative of one’s shifting personality.

What was college if not a series of “position takings”? Much more, of course, but the early Facebook couldn’t be faulted for failing to embody the complete college experience. It even became something of a norm to greet a friend in the dining hall by declaring, for example, “I see you added Trotsky to your list of favorite authors—but dropped Marx!” The site contributed in some small measure to what Thoreau, a student at Harvard two centuries before Zuckerberg, judged the unacknowledged but most significant part of the curriculum: “Tuition, for instance, is an important item in the term bill, while for the far more valuable education which [the student] gets by associating with the most cultivated of his contemporaries no charge is made.”

The first sign that Facebook might cause trouble came, for many, when a few unexpected members showed up—those who didn’t attend your college, or at least one of the same caliber. Especially for students who had graduated from a public high school and then gone on to an elite private college, the addition of state universities marked a turning point, as former classmates joined the site and started asking to be “friends.” A major attraction of the early Facebook, it was suddenly apparent, came from its snob appeal—the fact that some had been kept out, and only a highly selective few let in.

The mechanics of these “friend requests” are worth describing in some detail. Within a single college, in the early days of the site, everyone could see everything. You “friended” a fellow student not to see her page but to add her name and picture, like a trophy, to your list of friends; this “friend list” then appeared not far from your lists of favorite books and favorite music, more evidence of your discriminating tastes, or proof of your popularity. If a college acquaintance wanted to look at your page, she could simply type in your name—just as she might glance your way on the quad, or eavesdrop on your conversation in the dining hall.

Zuckerberg, however, cordoned off each college from all others. The “friend request” then took on a new function, becoming the means of authorizing people at other schools to see your page. The only way someone at a state university, for instance, could access the page of a student at a private college was by asking to become “friends.” But unlike when a student at a private college might run into an old acquaintance on winter break, it was impossible to politely respond to such a request while giving little away. You had to say yes or no.

Bourdieu, it now appeared, might have been right. When Facebook had been limited to a few elite schools, listing Beethoven among one’s “favorite music” could easily stand as a statement of aesthetic discovery. This was due to that other salutary fiction of an elite meritocratic education: that class distinctions disappear, to be replaced by pure judgment and analytic reason. But beneath the gaze of one’s former classmates, such a claim might well come off as a pose. It was no longer possible to treat the site as an extension of an elite college—the private haunt of one’s “most cultivated” contemporaries.

Advertisement

The class basis of Facebook’s early success is most evident in comparison with its greatest rival: MySpace. To join Facebook, you needed a college e-mail address; for everyone else—once Friendster, for various reasons, became less popular—there was MySpace. The result, as David Brooks observed in 2006, was a “huge class distinction between the people on Facebook and the much larger and less educated population that uses MySpace.”

Even after Facebook opened its membership, successively, to high schools, corporations, and the world at large—trying to capitalize on the site’s early success, which, Zuckerberg and his inventors hoped, was due to more than mere exclusivity—class distinctions remained important. Danah Boyd, a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society who is one of the best- informed academics studying social networks, wrote a much-discussed essay in 2007 that laid out, in broadly stereotypical terms, the preferred sites of many high school students:

The goodie two shoes, jocks, athletes, or other “good” kids are now going to Facebook. These kids tend to come from families who emphasize education and going to college…. MySpace is still home for Latino/Hispanic teens, immigrant teens, “burnouts,” “alternative kids,” “art fags,” punks…and other kids …whose parents didn’t go to college, who are expected to get a job when they finish high school.

One of the most notable examples of class distinction, as Boyd noted, came from the US military, which permitted soldiers to use Facebook but banned MySpace in 2007:

Facebook is extremely popular in the military, but it’s not the [social network] of choice for 18-year-old soldiers, a group that is primarily from poorer, less educated communities. They are using MySpace. The officers, many of whom have already received college training, are using Facebook.

MySpace remains banned within the military to this day, while Facebook, despite security concerns, is still available to American troops.

The importance of class was also evident in the sites’ aesthetics. Facebook has always been praised for its “clean” design, as opposed to the “lascivious, spam-ified, knife-wielding clutter of MySpace” (New York), with its “shrieking typography and clamorous imagery” (The Chronicle of Higher Education). But as Julia Angwin documents in her book Stealing MySpace, the site’s aesthetic came from its members. MySpace early on tried to impose fairly severe restrictions on how pages could be constructed; these restrictions, however, were easily circumvented, and MySpace’s engineers, who were not particularly competent programmers, declined to repair the holes revealed by hackers.

While MySpace listed details similar to if less sophisticated than Facebook—“Education,” but also “Body Type” and “Zodiac Sign”—a MySpace page could otherwise look like almost anything else online. Every Facebook page, by contrast, was laid out in exactly the same way, painted in an inoffensive if antiseptic palette of pastel blues on bright white. Facebook’s engineers, much abler than their counterparts at MySpace, quickly stifled any attempts to break these rules. To call MySpace “ugly” would be roughly equivalent to categorically denouncing graffiti—to praise Facebook for its “clean” design, akin to celebrating tract housing.

MySpace’s more permissive atmosphere and working-class aesthetic help explain why Rupert Murdoch paid $580 million for the site in 2005. The surprise came when Facebook, an apparently elitist Web site, caught on with members of all classes and succeeded MySpace in early 2009 as the most popular social network in America. Facebook now has more than 350 million members worldwide, with over 100 million in the United States. Facebook managed to beat MySpace—while Fox TV and Fox News ruled the airwaves—by appealing to what has become the largest new market for social networking: parents.

Most parents avoided MySpace, ironically, for the same reasons that drew Murdoch to the site to begin with: its central place in the media category euphemistically known as “urban culture,” which dominates contemporary American broadcasting, despite the fact that more than half of Americans now live in the suburbs. The best MySpace pages showed all the flair of MTV Cribs, the notorious TV show profiling the mansions of rappers, film stars, and other artists of “bling” and excess. Parents, unsurprisingly, were put off: a MySpace page was not simply something you sat back and watched, like the “urban” reality shows that fill American TV programming, or listened to, like the hip-hop music that pipes through American stereos; a MySpace page constituted one’s digital home, its basic “outside” version seen by everyone, its more revealing “inside” reserved for one’s friends, whom one has approved to see personal information. While many teenagers may prefer to decorate their rooms with the paraphernalia of hip-hop and drugs—and still continue to use MySpace in huge numbers—their parents have chosen to live in the suburbs for safety, privacy, quiet, and architectural uniformity, qualities that Facebook alone was prepared to provide.

As Facebook expanded from colleges to the rest of the public, always retaining tight control over how every page appeared, the site’s aesthetics thus began to seem less comparable to the dorm room design principle of in loco parentis and more akin to the authoritarian building codes of a planned community. Facebook did allow members to begin personalizing their pages with elements built by outside programmers. But the basic layout of one’s page couldn’t change; each new addition had to be slotted into Facebook’s rigid design. This was the predominant mode of what might be called Facebook’s “suburban period,” which began in September 2006 and continues, in many ways, into the present. We can pinpoint the start date so precisely because at the same time that Zuckerberg opened Facebook to anyone who wanted to join, he launched a function that has since come to dominate the site: the “News Feed.”

The News Feed, as the name suggests, resembled a personalized wire service. “Imagine a device that monitors the social marketplace the way a blinking Bloomberg terminal tracks incremental changes in the bond market,” The New York Times described the new feature at its debut. But I would propose an alternate metaphor: the suburban backyard fence. Facebook, when restricted to colleges, had relied on the typically intense social lives of students in the dorm room and at the dining hall. It was possible to obsessively check the pages of a few good friends or a cute girl in your class, but you could easily ignore everyone else.

The News Feed, by contrast, made everyone and everything an object of gossip by automatically sending the minutest changes to a wide circle of “friends.” Along with the pleasure of learning that a crush had added Godard to her list of favorite filmmakers, you had to endure image after image of the drunken escapades of people you hadn’t seen in years. New features were supposed to screen out some “friends,” but these settings barely worked.

Hundreds of thousands of members would subsequently join Facebook “protest groups” to complain about the News Feed, as they have with each new redesign. But Facebook only reversed course after the most egregious mistakes (e.g., a program that broadcast a person’s online purchases to hundreds of “friends,” ruining many surprise presents as well as revealing a few prurient tastes). Instead, Zuckerberg handed down each new redesign by assuring members that they would learn to appreciate the changes in time. As he reportedly bragged to employees last spring: “The most disruptive companies don’t listen to their customers.” Although Zuckerberg is here parroting Clayton Christensen, the Harvard business professor who coined the term “disruptive innovation” to describe many technological changes, it’s not hard to hear an echo of Robert Moses.

The result of these changes, especially as Facebook expanded and more and more parents, employers, and teachers signed up, was to induce a chilling and puritanical atmosphere. Few members actually quit—the ability to check up on everyone you knew, whenever you wanted, had grown too addictive, and MySpace and later Twitter offered even less privacy—but much of the playfulness of the early Facebook disappeared. Many students can recount the story of an aunt, say, who joined Facebook, looked up her nephew, and, even without sending a formal “friend request,” discovered, among the limited information available to every member, that little David was listed as “married” to someone of the same sex. And his mother hadn’t even told her he was gay—let alone invited her to the wedding!

The more typical problems arose because of compromising photos. Shortly after the site launched, Facebook began allowing members to upload entire albums; today it hosts more photos than any other site. If an employer happened to have attended the same college as a young job candidate, and used an alumni e-mail address to create an account on Facebook, a huge number of photos could easily be discovered. Alumni were automatically considered part of their college, and thus could see the pages of most current students, another sign that the site’s founding principle was exclusivity, not, as Zuckerberg and others so often claim, privacy. A Times story from mid-2006 gives a classic example:

Ana Homayoun runs Green Ivy Educational Consulting…. Curious about [a] candidate, Ms. Homayoun went to her page on Facebook. She found explicit photographs and commentary about the student’s sexual escapades, drinking and pot smoking, including testimonials from friends. Among the pictures were shots of the young woman passed out after drinking.

Facebook provided a way to dissociate yourself from incriminating photos, but by the time you did so it might well be too late. My favorite story may be that of the young banking intern who informed his boss he had to miss work because of a “family emergency.” Before the intern could hide the evidence, his coworkers discovered the true nature of his emergency—he showed up on the News Feed in photos from a Halloween party, dressed as a woodland fairy, with a can of Busch Light in his hand.

These are the by now shopworn anecdotes of the “Facebook Generation,” the stories that make those born before the Internet revolution wonder whether today’s “digital natives” will ever know the true sweetness of privacy. What has been less widely reported is the way many young members responded to these scandalous episodes: by manicuring their profiles and privacy settings as carefully as a suburban front lawn. The ironic marriages amicably ended; the bragging about drug use, or even a taste for bad music, was erased; the site removed “Random Play” and “Whatever I Can Get” from the options of what members were “Looking For”—to be replaced by “Networking.”

Six years after its founding, Facebook still hasn’t made it possible for users to approve what pictures others may “tag” with their names. One solution: set your privacy options so that no one could see your photos at all—a decision whose wisdom would be confirmed every time a drunken picture of a friend showed up on the News Feed, only to disappear a few hours later, like a Cheeveresque husband seen momentarily wandering, naked, down his front drive.

Given the common fatalism about the “death of privacy,” I find it encouraging that Facebook’s problems have resulted not from a complete lack of privacy, but rather from widespread paranoia about whether the site’s privacy system could be trusted. Before the site launched in 2004, an insistence on online privacy had come to seem, at least in cutting-edge quarters, like a kind of snobbery. Facebook, precisely thanks to the elitist nature of its founding, was able to show millions of college students—those who use the Internet most—that excluding the wider world actually expanded what you could do online. As we have known offline for centuries, and as these students learned on the Web, there are many things, from party photos to Marquis de Sade quotes, that one might comfortably pin over a desk or hang on a wall, but that would best not be made visible to just anyone online.

Over the past year, though Facebook continued blundering its way through each new update—recently encouraging members to make their profiles more public than many might like—it also began to show the first indications of a robust privacy system. If Facebook doesn’t continue to improve its privacy options, members may well leave for a site that will. As Facebook’s privacy settings grow ever more sophisticated, and especially as members become more adept at using them, a new era in privacy on social networks will begin.

One little-reported effect of the latest settings, for instance, was their ability to effectively deal with divorce. In the past, many estranged parents, who perhaps hadn’t communicated in years, often found their comments yoked together in a “conversation” beneath a child’s posts. Now, in what might be taken for a sign that the site has moved beyond its early “suburban period,” it has become possible for users to effectively break a family into groups, each receiving different pictures and posts. These advances in privacy will soon be accompanied by advances in aesthetics: many social networks, including Facebook, have begun to allow members to stop using the sites themselves, with their stifling visual restrictions, and to construct digital “homes” of their own, making use of the basic services of the old social networks as if they were public utilities.

But Facebook doesn’t want to simply branch out onto a few more Web pages; the site hopes, in a somewhat sinister but potentially very useful (and profitable) way, to begin following us around the entire Web. This is the ambition of “Facebook Connect,” a special service that members may activate, and that has enabled many popular Web sites, such as Netflix, YouTube, and the Huffington Post, to tie activity elsewhere on the Internet back to Facebook profiles. If you leave a response on a Huffington Post story, for instance, it can, via Facebook Connect, automatically be shared with your friends on Facebook; subsequent responses by Facebook friends could eventually appear both on your Facebook page and on the original Huffington Post story.

If Facebook Connect is widely adopted—and the service has been quite successful so far, with Yahoo and even MySpace signing up—we may begin to see changes to many of our basic assumptions about the Internet. Once a commenter knows that a vitriolic statement will be shared with a large and personal social circle—appearing more like a letter to a small-town newspaper than an anonymous outburst—the typically venomous atmosphere of online comments, for example, may well diminish.

Facebook Connect could also have a strong effect on politics. The widely celebrated MyBarackObama.com was in some ways only an early sign of how social networking may yet affect campaigning. The site, while quite popular, with over two million members during the campaign, suffered from several inherent problems. To join, you had to go through the process of signing up for yet another online account, with a new name and password, easily forgotten; and what you did there—whether watching a speech, calling voters, or signing up for canvassing—was shared only with your connections on the new private network, who you would have to go to the trouble of finding and “friending” once again. Members could send out separate e-mails about each campaign event they planned to attend, but these are precisely the small social “friction points” that social networking is supposed to eliminate.

The Obama campaign made use of Facebook by creating a campaign page for the candidate, which attracted over 2.2 million supporters, all of whom received daily updates from the campaign. But one of the primary uses of Facebook has always been for discovering events—such as concerts or literary readings—that friends plan to attend. If you could see on Facebook which campaign events your friends have volunteered for, many members, particularly those interested in politics but not heavily committed, may be more likely to get involved. MyBarackObama added Facebook Connect in October 2008, but the service was still new and few used it. Therefore, much as online fund-raising was pioneered by Howard Dean in 2004, only to be perfected by Barack Obama in 2008, I would suggest, the role of social networking in 2008 may look rather minor from the perspective of 2012.

We can see the potential effect of Facebook on politics in the way the site has already begun to change another kind of campaign: advertising. A business can now create its own “Fan Page,” which looks much like any other Facebook page, except instead of a home it acts as a storefront. Members can then click to become “fans” of the product or, in the case of public figures, person: whether of The New York Review (12,000), the Metropolitan Opera (30,000), Paris Hilton (160,000), Coca- Cola (four million), or Barack Obama (seven million).

Once members have signed up as “fans,” they receive updates from these companies and public figures, just as they receive updates from their friends. The result is about as close to word-of-mouth as marketing can get. While it may seem surprising that so many people would sign up for the privilege of receiving advertisements, the information that companies and organizations share doesn’t differ that much from old-fashioned newsletters—Renée Fleming is at the Met! Paris Hilton is running for president! Barack Obama is giving a speech on Haiti!

The more disturbing aspect of Facebook’s involvement with advertising can be seen in the site’s plans to generate revenue. Rather than charging businesses for “fan pages,” Facebook sells advertising that then appears elsewhere on the site, as a way for businesses to build brands and solicit more “fans.” Because of its unparalleled demographic information, Facebook can sell ads that will appeal only to carpenters in one small town in Vermont, or to graduates of the Harvard Business School, or to residents of Manhattan who list “opera” as an interest. The site could also provide the most highly targeted political ads in history. Google can sell ads that will appear in a particular locality, as Scott Brown showed by buying up much of the online ad space for Massachusetts during the final days of his successful bid for the Senate. With Facebook Connect, it may be possible to show ads specifically targeted to Massachusetts residents who use words such as “Irish,” “Italian,” or “black” in their profiles, or who list their religion as Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish. So far, however, advertising has only provided enough revenue for the site to barely break even, and many believe the site can only claim to be profitable because of creative accounting.

Facebook Connect, if it becomes widely used across the Internet, would enable Facebook to sell ads not just on its own pages but elsewhere as well. Google makes its largest profits through “search advertising,” where a query for “insurance” will result in ads for companies such as Geico or Allstate. But Google has never been as successful at “display advertising,” the name for the ads that show up beside everything online—from party photos to news stories—where it’s not clear what, if anything, users want to buy. Facebook, with much more precise information about its members, will likely be able to sell far more effective display advertising than Google. Whether members will be disturbed by this expansion of targeted ads—a person who lists her religion as “Jewish” may see Jewish-themed advertising not just in Commentary magazine but on every Web site she visits—and whether ever more targeted advertising will turn members off the site—does listing a love for the Marquis de Sade mean you want ads for leather?—remains to be seen.

If Facebook Connect spreads through the rest of the Internet, it will begin to produce even more radical effects. Google, the dominant force on the Web for the past decade, explicitly stated its goal at the company’s founding: “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible.” But there are some things that many would rather not make universally accessible—and not just books under copyright. Facebook, with the private information of over 350 million members, now constitutes what Wired magazine has called a “second Internet.” By encouraging members to bring their Facebook settings with them onto the rest of the Web, Zuckerberg hopes to take this new Internet, with its pretensions to privacy, and place it at the foundation of the old one.

While Zuckerberg’s ambition to reduce the experience of the Internet to a more human scale should be applauded, his site, despite its recent openness, prevents users from transferring their information to other social networks—a restriction, considering the huge time and effort many members put into their profiles, akin to prohibiting homeowners from packing up their houses and moving elsewhere. Moreover, with the site’s huge database of personal information and its hopes to profit from highly targeted ads, Facebook creates its own surveillance problems. If anything, Zuckerberg looks, in some distant but discernible way, like the Robert Moses of the Internet, bringing severe order to a chaotic milieu. While several efforts have been made to create more open versions of social networks, none has found much success. We are still waiting for the Jane Jacobs of online “urban planning” to appear.

What many find most enticing about Facebook is the steady stream of updates from “friends,” new and old, which sociologists refer to as “ambient awareness.” This is not a new phenomenon: everyone from our Cro-Magnon ancestors to Jane Austen has known how it feels to be surrounded by the constant chatter of other people. Facebook’s continuing attraction comes from its ability to reduce the Internet’s worldwide chatter to the size of a college, or a village, or a living room. But it is this very old form of sociability, transferred into the electronic age, that, rather than targeted ads or aesthetic monotony, some members find troubling about the site. As the writer William Deresiewicz, by far the most eloquent critic of Facebook, recently argued in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

We have turned [our friends] into an indiscriminate mass, a kind of audience or faceless public. We address ourselves not to a circle, but to a cloud…. Friendship is devolving, in other words, from a relationship to a feeling.

It’s true that Facebook can lead to a false sense of connection to faraway friends, since few members post about the true difficulties of their lives. But most of us still know, despite Facebook’s abuse of what should be the holiest word in the language, that a News Feed full of constantly updating “friends,” like a room full of chattering people, is no substitute for a conversation. Indeed, so much of what has made Facebook worthwhile comes from the site’s provisions for both hiding and sharing. It is not hard to draw the conclusion that some things shouldn’t be “shared” at all, but rather said, whether through e-mail, instant message, text message, Facebook’s own “private message” system, or over the phone, or with a cup of coffee, or beside a pitcher of beer. All of these “technologies,” however laconic or verbose, can express an intimacy reserved for one alone.

This Issue

February 25, 2010

Food

A Deal with the Taliban?

The Triumph of Madame Chiang