Who’s Next?

First we got the bomb, and that was good,

‘Cause we love peace and motherhood.

Then Russia got the bomb, but that’s okay,

‘Cause the balance of power’s maintained that way.

Who’s next?Then France got the bomb, but don’t you grieve,

‘Cause they’re on our side (I believe).

China got the bomb, but have no fears,

‘Cause they can’t wipe us out for at least five years.

Who’s next?…

South Africa wants two, that’s right:

One for the black and one for the white.

Who’s next?Egypt’s gonna get one too,

Just to use on you know who.

So Israel’s getting tense,

Wants one in self defense.

“The Lord’s our shepherd,” says the psalm,

But just in case we better get a bomb.

Who’s next?Luxembourg is next to go,

And (who knows?) maybe Monaco.

We’ll try to stay serene and calm

When Alabama gets the bomb.

Who’s next?

Who’s next?—Tom Lehrer, 1965

The following is a statement by A.Q. Khan, the Pakistani entrepreneur who sold nuclear weapons internationally:

If you want to buy a thing, you place the order directly and you get it. If you don’t give me [the item] for one reason or another, I ask Tom, Dick or Harry [for] this item. Could you please buy it for me? Okay, no problem. It is a commercial deal. The guy buys from you. You are not willing to sell it to me, but you are willing to sell it to Tom. So, Tom buys from you. He takes ten or fifteen percent and he says to me that this is purely a business deal.1

On January 7, 1939, Niels Bohr, his son Erik, and Bohr’s assistant Léon Rosenfeld left Copenhagen for the United States. Four days earlier, the Austrian-born physicist Otto Frisch, who had taken refuge in Bohr’s Copenhagen Institute, had told Bohr about the work that he and his aunt Lise Meitner had just done in Sweden. Drawing on experiments by the radio chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman—Meitner’s former colleagues in Berlin—Meitner and Frisch showed that it was possible to split uranium nuclei by bombarding them with neutrons. Over the years I have spoken with several physicists who were active in 1939 when this discovery was made. All of them, including Bohr, could not understand why they had not predicted it themselves. Robert Serber, a physicist recruited for the Manhattan Project in 1941 who played an essential role at Los Alamos, said to me, “How could we have been so stupid?” This was the discovery that made nuclear weapons possible.

The uranium that Hahn and Strassman used in Berlin was natural uranium from a mine. It consisted of two predominant isotopes: uranium-238 and uranium-235. Isotopes of atoms have nuclei that contain the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons; uranium-238 and uranium-235 differ by three neutrons. Over 99 percent of natural uranium is uranium-238, but Bohr realized that only the uranium-235 fissioned in these experiments. Moreover the process was such that any neutron—regardless of the amount of energy it contained—would cause a uranium-235 nucleus to split, while it took a minimum threshold of energy for a neutron to induce fission in uranium-238. Thus the distinction between “fissile” nuclei—U-235—and “fissionable” nuclei—U-238—was discovered.

As soon as uranium fission was considered for nuclear weapons, it was understood that the fissile isotope was the relevant one. I think that Bohr greeted this news with a sense of relief. Separating these isotopes was so difficult that, as he put it, it would take the resources of an entire country; and he felt that no country would devote its resources to it, so the notion of atomic weapons could be safely ignored.

In fact it took the resources of three countries to produce the bomb: the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. But there was more to it than that. In some sense it took some of the most valuable scientific talent of all Europe to do it. Consider this partial list: the Hungarians John von Neumann, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller; the Germans Hans Bethe and Rudolf Peierls; the Poles Stanisław Ulam and Joseph Rotblat; the Austrians Victor Weisskopf and Otto Frisch; the Italians Enrico Fermi and Emilio Segrè; Felix Bloch from Switzerland; and, from Denmark, the Bohrs, Niels and his son Aage. Almost none of these people went back to their native countries after the war, but people like Peierls and Frisch did return to England, their adopted country, and they and some others began work on making nuclear weapons there.

Advertisement

Proliferation was inevitable and had been predicted. What had not been predicted was the extent to which it would be abetted by espionage. The German-born physicist Klaus Fuchs, who had been part of the British delegation at Los Alamos and returned to England where he worked on nuclear weapons, gave the Russians what was essentially the blueprint of the bomb the US used at Nagasaki. He is in the unique position of having helped three countries build nuclear weapons. Nor did anyone foresee that proliferation of nuclear weapons would become a commercial enterprise, which is the situation that we find ourselves in at the present time.

At the center of this activity is the Pakistani metallurgist A.Q. Khan and his collaborators. A great deal has been written about them—including by me in these pages2—but I have never found an account as detailed as the one in Peddling Peril: How the Secret Nuclear Trade Arms America’s Enemies, by the nuclear armaments expert David Albright. Albright holds master’s degrees in physics and mathematics and has taught physics. For five years—between 1992 and 1997—he was part of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Action Team and in that capacity he spent time as a weapons inspector in Iraq. In 1993, he founded the Institute for Science and International Security, a nonprofit research organization based in Washington, D.C., of which he is president.3

In short, Albright is a perfect person to write a book like this. As he recounts, Kahn’s first customer outside Pakistan was Iran. By 1984 the Islamic Republic had decided that it needed gas centrifuges to enrich uranium, which Iranian officials knew had been done by Pakistan. Masud Naraghi, an Iranian engineer with a Ph.D. in plasma physics from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, was given the job of buying the necessary information and equipment from somewhere.

Needless to say, the “somewhere” was the network of suppliers that Khan had set up. One of these was a firm in Cologne called Leybold-Heraeus. Among other things, this company had devised a way to place centrifuges in a vacuum to reduce friction, so that the rotors in them could spin faster than the speed of sound. The company had managed to get some of this equipment to Kahn by the usual tactic of claiming that it was “dual use”—i.e., that it had civilian applications—or by shipping it to dummy companies in places like Dubai that had lax or nonexistent export and import regulations. Naraghi seemed to know enough about the Pakistani program to arrange visits to the Leybold plant in Cologne. One of the people he met there was a German engineer named Gotthard Lerch.

Lerch was a perfect collaborator. He had absolutely no scruples about selling anything to anybody as long as he could skim a percentage of the sale. He also understood what Naraghi wanted without Naraghi having to say anything about centrifuges, let alone what they were going to be used for, which gave everyone involved deniability. Lerch presented Naraghi with an entire menu of centrifuge parts to choose from. In February 1987, the Iranian government secretly signed a deal (approved by then Prime Minister Mir Hossein Moussavi) to get some used Pakistani centrifuges of the P1 design, as well as the plans for the P2 centrifuge, the P1’s successor.

The Iranians paid between five and ten million dollars, of which Lerch got the lion’s share and his sources in Pakistan the rest. The unanswered question is whether the package also included the Chinese design for a nuclear weapon that Khan had obtained. Most people I have asked are quite sure that it did. In any event this sale became the basis of Iran’s uranium enrichment program.

In the fall of 1990, shortly before the Gulf War, Iraq had some dealings of its own with Khan. Little came of them, although Albright notes that during the 1980s Baghdad had previously been able to obtain “large quantities of technology, equipment, and materials for Iraq’s nuclear programs from a range of countries including Britain, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Japan, Brazil, and the United States.” However, as Hans Blix, the former chief weapons inspector for the United Nations, has repeatedly stated, UN weapons inspectors concluded from their own inspections in Iraq that the program was dismantled shortly after the Gulf War. “[Iraq’s weapons] were destroyed in 1991,” Blix told Tim Russert on Meet the Press in 2006.

Libya was another matter. In 1997, after some maneuvering, Libya finally bought a package from the Khan network for somewhere between one and two hundred million dollars. The deal included ten thousand P2 centrifuges, which, if they had been installed, could have produced about a hundred kilograms of weapons-grade uranium per year, enough for several weapons of the Chinese design that the Libyans also bought from Iran (a device in which attached hemispheres of fissile material would be imploded using high explosives). Needless to say the Libyans tried to conceal all this but it was revealed in 2003 when some centrifuge parts were shipped from Dubai aboard a German ship, the BBC China. Because some members of the Khan network had been turned, the CIA knew about this shipment and an American naval vessel trailed the ship. The captain was persuaded to dock in the Italian port of Taranto. The ship was searched, and the illicit cargo seized. This persuaded Colonel Qaddafi that there was no future in nuclear weapons and he turned what he had received from the Khan network over to the CIA. The network itself was dismantled although, as Albright writes, one cannot be sure that all of the companies and arms dealers involved in it have been shut down.

Advertisement

One of the places where the unraveling of the Khan network took place was South Africa. The history of nuclear weapons in South Africa is so interesting that Albright has said that it will be the subject of his next book. He devotes a chapter to it here. When Tom Lehrer wrote his song in 1965, he had no way of knowing that nine years later the South Africans would begin a nuclear program for what they said were “peaceful applications.”4 It soon openly morphed into a program for making nuclear weapons.

There were at the time 50,000 foreign troops in Angola and considerable racial unrest in South Africa itself; in his song Lehrer wrote, “South Africa wants two, that’s right: One for the black and one for the white.” At the time nothing in South Africa escaped race. Only South African–born white citizens were allowed to work on the actual weapons design. A South African scientist connected with the nuclear program told me that naturalized white South Africans were allowed to work on uranium enrichment while black South Africans mined the uranium.

Like any country entering the nuclear weapons business, the South Africans had to decide which route to take. They chose the simplest solution: an enriched uranium device called a “gun assembly.” In this device two masses of uranium below the critical level are fired at each other to make a critical and ultimately a supercritical explosive mass. This was the principle of the Hiroshima bomb. The Los Alamos people were so confident that it would work that, while portions of the device were tested, the bomb itself never was. Hiroshima was its test.

In contrast to this bomb design, an implosion device—the kind used in Nagasaki—consists of a sphere of uranium or plutonium that is compressed by high explosives. This increases the density of the material, lowering the critical mass. The technical difficulties here are much more substantial but in the end much less nuclear material is needed for a given explosive yield, so these weapons can be made more powerful than the gun assembly bombs. To make a gun assembly weapon you would need something like fifty kilograms of highly enriched uranium while a plutonium implosion device might use only six kilograms of plutonium.

The catch is that the uranium must be enriched to about 90 percent uranium-235 to make an explosive chain reaction. This is what the centrifuges are for. But the South Africans chose a method that was never used before on an industrial scale and has never been used since. In a centrifuge the cylinder containing the gas rotates, producing the centrifugal force that separates the isotopes. The South Africans injected the gas into curved tubes at very high speeds. The molecules ran around this curved track like racing cars and the same centrifugal force was produced. But it was a very inefficient and energy-consuming process.

The work was carried out in what was known as the Y-Plant in Valindaba, some forty-four miles northwest of Johannesburg. But in August 1979 there was an explosion that put the plant out of operation for two years. It was repaired and then proceeded to enrich enough uranium for at least seven weapons. The South Africans have never revealed what their stock was but it must have been over 350 kilograms.

Waldo Stumpf, who is now a professor in the materials and metallurgy department at the University of Pretoria, joined the South African nuclear program as an engineer in 1968. By the late 1980s he was head of the country’s Atomic Energy Corporation, which ran the program. Lerch, who had a remarkable talent for finding possible customers, had some South African members of the Khan network contact the corporation to try to sell them centrifuge components, some of which were being manufactured in South Africa. Stumpf decided that he would not deal with the Khan network; in any event South Africa had what it needed.

Then, in September 1989, F.W. de Klerk became president of South Africa. Not only did he free Nelson Mandela in 1990 but he also decided to dismantle the entire nuclear weapons program. I think that the two events were connected. I doubt that he wanted to turn over six completed nuclear weapons to the African National Congress. Some of the enriched uranium is now being used in the South African Safari reactor—one designed to make medical isotopes that South Africa exports—and some is under international supervision.

Still, this did not eliminate the Khan network in South Africa, some of whose operatives had been previously employed by the official program. Among them was Johan Meyer, an engineer at Valindaba who left the program to start his own company, which manufactured tubes that were used with centrifuges. A German named Gerhard Wisser and a Swiss named Daniel Geiges were part of the Khan network. They were in touch with both Lerch and Meyer. Soon Meyer was clandestinely shipping centrifuge parts from South Africa to Libya with everyone pocketing the money, of which there was a great deal. But when the Khan network was unrolled, Meyer turned state’s evidence and testified against his former collaborators.5 Lerch was also arrested and spent a year in custody. Wisser and Geiges reached a plea agreement and Meyer escaped jail altogether. His company, Tradefin Engineering, still exists in Vanderbijlpark, a town close to Johannesburg. I am not sure what it manufactures. I e-mail them a question about this from time to time but have not gotten an answer.

Perhaps the most chilling chapter in Albright’s book is entitled “Al Qaeda’s Bomb.” As far as we know al-Qaeda does not have a bomb, but it is not for lack of trying. I hope it is clear from what I have written that the notion of terrorists making atomic bombs in caves from anything like scratch is absurd. If they were able to get hold of radioactive isotopes, they might make a “dirty bomb” that would spread these isotopes using high explosives. This would create a terrible weapon but it would not destroy a city or even a large part of one. What they might try to do is to buy a bomb or the component parts from a rogue nation. North Korea is a good possibility, but one should not overlook Pakistan. Albright writes that fundamentalists in the Pakistani nuclear program have tried for many years to convey such material to people like Osama bin Laden.

Before the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, the Pakistanis had free-ranging contacts with and through the Taliban. Albright writes:

Over two or three days in August 2001, [Pakistani scientists] Mahmood and Majeed had long discussions with Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and two other al Qaeda officials about the development of weapons of mass destruction, providing detailed responses to bin Laden’s technical questions about the manufacture of nuclear weapons….

Several other Pakistani nuclear scientists were contacted by representatives of the Taliban government and al Qaeda seeking assistance to create a nuclear program inside Afghanistan. Out of those, two unnamed Pakistani scientists who were veterans of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons complex and associates of Mahmood and Majeed were amenable to al Qaeda’s overtures (one of the two was already under suspicion for trying to sell weapon designs).

There are huge quantities of fissile material throughout the world and it does not take much to make a crude bomb. There have been incidents of the theft of such material—last year alone more than 250 cases of unauthorized possession, theft, and loss of nuclear or other radioactive materials were reported to the International Atomic Energy’s Illicit Tracking Database. We must be vigilant and hope that the international conference of heads of state that took place in Washington in April will eventually lead to effective measures to secure nuclear materials.

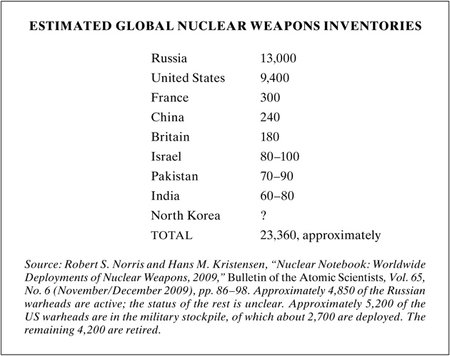

The Obama administration recently negotiated a new weapons accord with Russia calling for a reduction of the maximum number of deployed nuclear weapons on each side from 2,200 to between 1,500 and 1,675—some 30 percent (in addition, Obama has committed $15 billion over the next five years to improving the safety of the nuclear stockpile). But nothing in what has been announced, at least in what I have seen, has any direct relevance to bringing an end to the kind of proliferation I have been describing, and that continues even now. According to The Wall Street Journal, the IAEA is investigating new reports that an Iranian firm has been buying, through a Chinese intermediary, special French hardware for enriching uranium. Perhaps a new spirit of cooperation would be helpful. As Tom Lehrer asked in his song, “Who’s next?”

—April 14, 2010

-

1

Interview with Egmont Koch, August 17, 1998, quoted in Peddling Peril, p. 146.

↩ -

2

See my article “[He Changed History](/articles/archives/2009/apr/09/he-changed-history/),” The New York Review, April 9, 2009.

↩ -

3

Its Web site, [www.isis-online.org](http://www.isis-online.org), is an invaluable source for those who are interested in nuclear proliferation.

↩ -

4

See, for example, Waldo Stumpf, “Birth and Death of the South African Nuclear Weapons Programme,” at [fas.org/nuke/rsa/nuke/stumpf.htm](http://www.fas.org/nuke/rsa/nuke/stumpf.htm).

↩ -

5

The Institute for Science and International Security has made available documents from the case against Geiges, Wisser, and Krisch Engineering at [www.isis-online.org/peddlingperil/southafrica](http://www.isis-online.org/peddlingperil/southafrica).

↩