1.

On the streets of Warsaw and Kraków, alongside carved wooden figurines of Saint Nicholas and potbellied beer drinkers, they sell little Orthodox Jews, black-capped, black-garbed, and bearded. A few wear the tallit, the prayer shawl; others play the fiddle and the horn for klezmer music; but the great majority are sad-faced men with staring eyes and their hands held in front of them forming a slot in which is inserted not a prayer book but a złoty. I have severely undeveloped taste for kitsch and have no idea why people find these objects cute or funny. The yid always clings to money? Or the poor yid is down to his last cent? Or, when you are looking for money, you can always turn at last resort to a yid?

I am confident that a certain percentage of those who buy the figurines are themselves Jews, picking up a souvenir of their visit to Auschwitz or their package tour of the sites Steven Spielberg used in filming Schindler’s List. On the shelf back home the tchotchkes serve as a material reminder of the completed pilgrimage—like the little badges that Christian pilgrims in the Middle Ages used to buy at Santiago de Compostela—or perhaps as an emblem of the terrible fate that they, the modern pilgrims, somehow avoided.

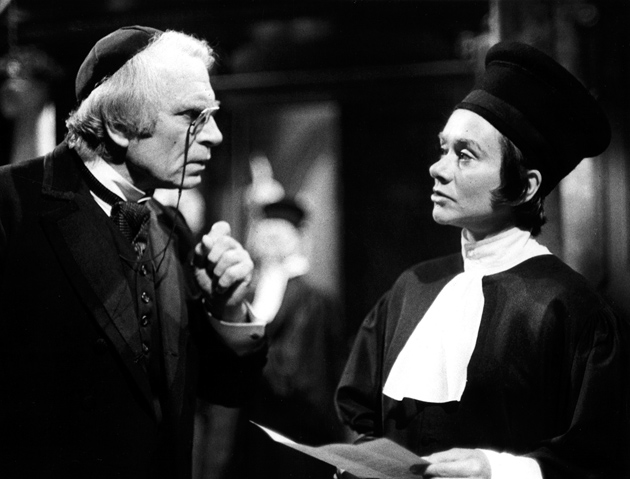

There were moments in the Public Theater’s recent Merchant of Venice, directed by Daniel Sullivan and performed at Shakespeare in the Park, in which Al Pacino’s rumpled, bearded Shylock uncannily resembled one of these Polish figurines. Pacino is, for a start, very short—next to Byron Jennings’s lean, anguished Antonio or Lily Rabe’s statuesque Portia, he looked positively shrunken in the black suit by costume designer Jess Goldstein, seeming more an animated block of hard wood than a creature of flesh and blood. (The sense that he was a manikin was heightened by the rapturous applause of the starstruck audience, which treated his mere appearance on stage as if it were an impressive conjuring trick, a celluloid image come to life.)

Pacino’s miming of a Jew was itself an odd piece of artifice, bearing roughly the relation to any imaginable Jewish reality that the figurines for sale in Warsaw bear to Roman Vishniac’s photographs of the doomed inhabitants of the ghetto. “Ay yam contendt,” his broken moneylender, reluctantly agreeing to convert to Christianity, declared in accents that only alluded to the way Jewish immigrants actually sounded. Pacino’s distance from the truth of my grandpa Mendel, my cousin Meyer, and innumerable others did not seem to me a sign of failure; rather it served simply to reinforce the still greater and more consequential distance between Shakespeare’s imaginary Jew and the real sixteenth-century Jews whom Shakespeare, the inhabitant of a country that in the wake of the expulsion of 1290 was effectively Judenrein, could not have encountered.1

In the earliest productions, Shylock was played with a bright red wig and a grotesque hooked nose. He was in appearance the wicked Jew of anti-Semitic fantasy, one of those hideous faces that leer at the suffering Jesus in paintings by Hieronymus Bosch. That Shylock has not always seemed completely fantastic—the equivalent of the Big Bad Wolf or the malevolent dwarf in “Rumpelstiltskin”—is the consequence of Shakespeare’s eerie, virtually uncontrollable ability to confer reality on whatever he chose to imagine. In the case of The Merchant of Venice, that ability put intolerable strains on the structure of the comedy, so that the last act, with its music and its banter about the rings, has proved almost impossible to bring off successfully.

To his credit, Daniel Sullivan does not even try for a comic finale: none of the lovers is remotely happy; disappointment, betrayal, and recrimination lurk just below the surface; and the playful vows to abjure the marriage bed forever have the queasy air of irrevocability. The flood of money cannot wash away the pain in Antonio’s face as pretty, petulant Bassanio waves him away, while lonely Jessica despondently drops the deed of gift her father has been forced to sign into the pool by which she sits. A few moments earlier, at the close of the previous scene, that pool had served as the baptismal font into which Shylock was shoved, and it is as if that vivid bit of stage business has contaminated its waters. “I am sure you are not satisfied,” Portia says in her final speech; never have words rung so true.

But the play’s structural defects are more than compensated for in the stupendous opportunity it has long presented to the actor playing Shylock. The great performances of our time have included Laurence Olivier’s neurotic, buttoned-up Victorian businessman, barely controlling the hysteria to which he is destined to succumb; Anthony Sher’s intellectual avenger who tragically fails at the last moment to do what he had set out to do; Henry Goodman’s unbearably poignant Weimar outsider caught up, along with Portia, in a spiraling horror neither of them can escape; and, more recently, Murray Abraham’s tormented, passionate father in a decadent Venice indifferent to his anguish.

Advertisement

Al Pacino does not belong in this company. His Shylock had no inner life or psychic resources, no baffled search for a source of comfort, no deep pathos, no gleeful intelligence, no sly comedy. Even his painful memories of his dead wife Leah, whose turquoise ring Jessica has stolen and traded for a monkey, lacked conviction. The poignancy of Shylock’s agonized protest—“I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys”—rests on that word “wilderness,” but Pacino let the emphasis fall heavily on “monkeys,” as if the question were whether Jessica had struck a sufficient bargain for so valuable an object. On such seemingly insignificant details, the complexity of a character is built—or, in this case, fails to be built.

But Pacino did convey one thing brilliantly: what Shylock calls “a lodged hate and a certain loathing” he feels for the Christian Antonio. All of the best moments in this production were built around this all-consuming hatred. “I’ll have my bond,” Pacino spat out again and again with insane rage and vindictiveness at the merchant kneeling before him. And in the courtroom, reiterating implacably, “An oath, an oath! I have an oath in heaven,” Pacino struck what seemed to be a prayer book in his hand: “By our holy Sabbath have I sworn/To have the due and forfeit of my bond.” The murderous hatred his Shylock feels is a religious obligation.

In some productions, the feeling is mutual, so that Shylock the Christian-hater and Antonio the Jew-hater are doubles, as the simple question asked in the courtroom seems to imply: “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?” But not in this production: Daniel Sullivan cut the line completely. No one in his right mind could confuse these two antagonists. The Christian characters are generally softened: Salerio and Solanio are harmless ciphers, Graziano is more gracious than grating, Antonio overcomes his reluctance and shakes Shylock’s hand even before their contract is agreed upon. Cuts remove the clown Lancelot’s horrible tormenting of his blind father and spare Portia her racist slur on the complexion of the Prince of Morocco.

All that is left then is Shylock’s hatred, and the question is what that hatred means, in this production and in the play that Shakespeare wrote.

2.

In the great courtroom scene, The Merchant of Venice stages an appeal to mercy as a universal human value that transcends all local enmities, all sectarian differences, all political and legal systems, particularly those that attempt to define, to restrict too narrowly, or to compel—Shakespeare’s word is “strain”—their desired results:

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath.

(4.1.179–181)

But Pacino’s Shylock listened to the words with an expression of weary contempt, as if he had heard of all this humbuggery before, presumably in the Christian sermons that Venetian Jews were forced to attend. Surrounded by the hostile goyim—the spectators in Sullivan’s production formed a kind of lynch mob—the Jew could easily detect, beneath the language of universalism, the allusion to the Lord’s Prayer:

Therefore, Jew,

Though justice be thy plea, consider this:

That in the course of justice none of us

Should see salvation. We do pray for mercy,

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy.

(4.1.192–197)

Portia’s talk of salvation anticipates the final solution to the dilemma of hatred that the play will shortly reach: the forced conversion of Shylock to Christianity.

“Forced” is perhaps not quite right. Compulsion is an unwelcome guest at comedy’s banquet. Christianity linked its eschatological hopes to the conversion of the Jews, but it did not want the generous offer of redemption to be enforced by the execution of those who refused to be saved. Jews could be made to feel the consequences of their stubbornness—spat upon, beaten, forced to live in ghettos, excluded from most occupations, wantonly robbed, and on occasion abandoned to the homicidal wrath of the mob—but they could not simply be told that they must convert or die. Hence in Shakespeare’s Venetian courtroom, Shylock’s “consent” is specifically solicited:

PORTIA: Art thou contented, Jew? What dost thou say?

SHYLOCK: I am content.

(4.1.388–389)

But of course, the duke has just declared explicitly that Shylock “shall do this, or else I do recant/The pardon that I late pronouncèd here.” The pardon in question is of a death sentence. So the guilty Jew, after all, is given the choice of losing his life or converting. He chooses, perhaps not surprisingly, to become a Christian and thereby to ratify his own absorption and that of his only child into the dominant religion and the dominant culture. And with that absorption, he quietly disappears.

Advertisement

Jews in the sixteenth century routinely called upon God to avenge their injuries at the hands of the goyim. Then, as now, the Passover Haggadah incorporated the bitter verses of Psalm 79:

Pour out Your wrath upon the nations which do not know You,

And upon the kingdoms which do not call upon Your name.

But the vengeance for which they prayed was the Almighty’s. Whatever they felt in their hearts, the inhabitants of the ghetto did not publicly declare their own murderous designs upon Christianity, and they did not in fact pose a threat to their persecutors. There were no Jewish gunpowder plots, no fraternity of assassins secretly meeting in synagogue basements.

Of course, medieval and Renaissance Europeans heard horrific stories about the Jews, and the fact that we now know those stories to have been untrue is obviously irrelevant to their contemporary impact. Chaucer’s prioress was not alone in rehearsing the myth that Jews routinely murdered Christian children. The myth, often linked to the notion that the victims’ blood was used to make Passover matzoh, had sufficient credibility to lead repeatedly to the trial and execution of Jews accused of ritual murder. As late as 1913 the charge was brought against Menachem Beilis in Kiev; Beilis was acquitted, but only when the jury split by a vote of six to six.

In his recent history of anti-Semitism in England, Trials of the Diaspora, Anthony Julius places Shakespeare directly in this sinister line. The Merchant of Venice, he writes, is “a blood-libel narrative subject to considerable elab- oration.”2 It would certainly have been possible for Shakespeare to exploit such lurid stories—after all, he had already tried a human pastry in Titus Andronicus—but in fact he chose not to do so. The difference can be gauged by glancing at those places where the actual blood libel is still circulating in all its old malevolence: rabidly anti-Semitic right-wing Christian websites, for example, or the pages of the government-controlled Saudi daily al-Riyadh.3 Shylock is a threat to the Christian community of Venice, but the threat has nothing to do with ritual murder. It has rather to do with his gnawing feeling of injury, and his consequent plotting of revenge.

Given Shakespeare’s lack of interest in the ancient anti-Jewish libels—there is no mention of poisoned wells, as there is in Marlowe’s contemporaneous Jews of Malta, let alone the making of matzoh with Christian blood—he could have depicted Shylock’s seething hatred as entirely his own, a pathology akin to that of Aaron the Moor, the hunchback Richard, or honest Iago. None of these villains represents an entire group; each is driven by something peculiar to himself. To be sure, the criminal drive always exists in some relation to its possessor’s whole life, a life that invariably includes group identifications. But the hatred that impels these characters is what pulls each of them out of the larger sociological category and makes them distinctive.

Shylock’s villainy is similarly his own, but it is also deeply, essentially implicated in his Jewishness. Take away Iago’s rage at being passed over for promotion and you would still have Iago; take away Richard’s deformity, important though it is, and you would still have the twisted mind of the evil Duke of Gloucester. Both would, we can be certain, find other grounds, if the need arose, on which to base their murderous designs. After all, Iago is not appeased when he gets his coveted promotion, any more than Richard stops contriving murder when he discovers that he can, after all, seduce a woman. But take away Shylock’s Jewishness, and he shrivels into nothingness. That shriveling away is indeed what happens at the end of the fourth act of The Merchant of Venice.

One other group identity in Shakespeare comes close to Jewishness in its power to motivate resentment. Edmund’s villainy in King Lear is directly related to the sufferings of an entire class of people: illegitimate children. To this extent the bastard resembles the Jew. But unlike Shylock, Edmund is determined to escape as fast as he can from the stigmatized group to which his birth has condemned him. His nature does not express his group identification but rebels against it. And though he commits appalling crimes, Edmund is not actually a hater, in the way that Shylock is. He connives against his brother and his father not because he hates either of them—if anything, he holds them in a kind of perversely affectionate contempt—but rather because he refuses to stay in the collective category assigned to him by his fate.

Contrast Shylock’s response, when ask to dine with Bassanio and Antonio:

Yes, to smell pork, to eat of the habitation which your prophet the Nazarite conjured the devil into! I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following, but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you.

(1.3.28–32)

Shylock’s disgust is not a protest against his condition: it is his condition, his fundamental identity. He does not want out; he wants to remain in this identity. He is aware of the Christian life around him: he knows that the gentiles eat pork, that for their carnival music they like “the vile squealing of the wry-necked fife,” that they amuse themselves by assuming “varnished faces,” that is, masks. He is not ignorant of their pleasures; he simply does not want any part of them. He has even read the gentiles’ scriptures. Hence his remark about the Nazarite’s conjuring or, a moment later, when he glimpses Antonio, his allusion to the publican from chapter 18 of Luke’s gospel:

How like a fawning publican he looks.

I hate him for he is a Christian;

But more, for that in low simplicity

He lends out money gratis, and brings down

The rate of usance here with us in Venice.

If I can catch him once upon the hip

I will feed fat the ancient grudge I bear him.

He hates our sacred nation, and he rails,

Even there where merchants most do congregate,

On me, my bargains, and my well-won thrift—

Which he calls interest. Cursèd be my tribe

If I forgive him.

(1.3.36–47)

“I hate him for he is a Christian.” It is as simple or as complicated as that. Here Daniel Sullivan had Shylock do something surprising. The words in Shakespeare’s text are meant to be a soliloquy: “Shylock, do you hear?” says Bassanio, noticing that the money-lender is lost in his own thoughts. But Pacino’s Shylock stepped to the side of the stage and spoke the lines to a boy, a yarmulke-wearing Jewish clerk working in his countinghouse. The Jew is offering instructions then to the next generation on the rudiments of Christian-hating. There is, he explains, a specific economic motive, but that motive is hardly separable from the collective hatred. After all, Antonio’s interest-free loans are a direct assault upon the Jews: “He lends out money gratis, and brings down/The rate of usance here with us in Venice.” When Iago starts adding to the reasons he hates Othello, the accumulation of motives, each pulling in a different direction, begins to mystify the deep source of his grudge. In The Merchant of Venice the motives reinforce each other and all lead back to Jewish hatred of Christians, “the ancient grudge” that Shylock says he bears.

The grudge is personal—it has a history of direct and extremely ugly encounters:

You call me misbeliever, cut-throat, dog,

And spit upon my Jewish gaberdine,

And all for the use of that which is mine own.

(1.3.107–109)

But this is not a story of personal antipathy alone; the grudge is “ancient” not merely because it extends back through all the years that Antonio has spat upon and cursed Shylock but because it extends back much further than that, through the long, painful centuries of Jewish-Christian relations. For the Jews those relations have led to the ghetto and the economic life that Sullivan sketches in the first moments of the play, when the Jews circle outside the gates of the bourse and are angrily shooed away. For the Christians they have led to the behavior that Antonio, ordinarily generous, loving, and somewhat depressive by nature, manifests toward the despised enemy, as if he felt compelled to act out a collective loathing. Shylock’s response to this outrageous treatment is, by his own account, also a manifestation of collective behavior:

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug,

For suff’rance is the badge of all our tribe.

(1.3.105–106)

Shylock stands out from that tribe. He does not bear everything with a patient shrug; he secretly plots revenge, and he does so on his own initiative. That is, he contrives what he calls the “merry bond” with Antonio out of his own head and not in a conspiracy with his fellow Jews. But unlike Richard, Iago, or Edmund, Shylock is not isolated: Shakespeare goes out of his way to identify him with the larger Jewish community within which he lives. The play, which depicts him as a rich man, could easily have shown him acting entirely on his own: the gold and jewels and ducats that his daughter Jessica steals from him, when she runs away with Lorenzo, provide ample evidence of the great wealth that the money-lender has carefully stored up in his house. Yet in his transaction with Antonio, Shylock immediately involves another Jew. “I am debating of my present store,” he says, when he is approached for the loan,

And by the near guess of my memory

I cannot instantly raise up the gross

Of full three thousand ducats. What of that?

Tubal, a wealthy Hebrew of my tribe,

Will furnish me.

(1.3.48–53)

Why does Shakespeare add the plot wrinkle of Shylock’s insufficient store of capital? It would obviously make sense to involve Tubal in this way if Shylock were trying to use him as an excuse to increase the rate of interest he is charging Antonio, but no such strategy is involved. Instead, extending his hand in friendship, Shylock declares that he is offering his Christian tormentor an interest-free loan. All he asks as security for this exceptionally kind offer is a zany pledge of the pound of flesh, a pledge whose significance is its complete worthlessness.

What is the point then of bringing in Tubal? The point is that in some sense the loan comes from the tribe as a whole; it is Jewish money. Hence when the enraged Shylock sees his chance to destroy Antonio, we get a brief, sinister glimpse out beyond the two Jews to the larger community:

Go, Tubal, fee me an officer. Bespeak him a fortnight before. I will have the heart of him if he forfeit, for were he out of Venice I can make what merchandise I will. Go, Tubal, and meet me at our synagogue. Go, good Tubal; at our synagogue, Tubal.

(3.1.104–108)

“I can make what merchandise I will”—Shylock is speaking for himself here, not for his fellow Jews. But the play has just made clear the reason for this apparent isolation: it is not that Shylock has separated himself off from his community but rather that he has never until this moment fully acknowledged in his own person his full identification with it. “The curse never fell upon our nation till now,” he tells Tubal, and then corrects himself: “I never felt it till now.” This is self-pitying, but as Pacino’s performance made clear, it is not an attempt to pull away from being Jewish. We are in effect watching the fashioning of full ethnic or religious identification, as if Shylock had until now held himself aloof from the communal account of what it meant to be Jewish.

For the most extreme Jew-haters, that collective identity amounted to an absolute, indelible, ineradicable otherness. And it is precisely that dream that Shylock acts out in the courtroom, as he grasps the knife he intends to use in fulfillment of his oath. Antonio underscores what this oath discloses: the specifically Jewish character of Shylock’s determination. “You may as well do anything most hard,” the victim bound for slaughter declares,

As seek to soften that—than which what’s harder?—

His Jewish heart.

(4.1.77–79)

Entirely untouched by what the duke calls “human gentleness and love,” Shylock seems to embody the limitless, unreasonable, inexplicable hatred that for Christians marked the essential affiliation of the Jews with the father of evil.

But in fact the long courtroom scene in The Merchant of Venice does not end with the revelation that Shylock is the offspring of Satan. It ends rather with the startling disclosure that Shylock’s hatred has its limits. To be sure, he does not succumb to Portia’s eloquent plea for mercy. “My deeds upon my head!” he insists, but then he adds, “I crave the law.” This craving for the law, here the desire to take Antonio’s life in a civil suit, marks the boundary beyond which Shylock dares not go. He has the opportunity to act—a sharp knife in his hand, the naked breast of his loathed enemy exposed and vulnerable, the chance to strike. He is merely waiting for the judge’s express permission. And when Portia discloses the legal wrinkle in the contract—“This bond doth give thee here no jot of blood./The words expressly are ‘A pound of flesh'” (4.1.301–302)—Shylock could still act. Portia makes this option clear in spelling out the consequences:

Therefore prepare thee to cut off the flesh.

Shed thou no blood, nor cut thou less nor more

But just a pound of flesh. If thou tak’st more

Or less than a just pound, be it but so much

As makes it light or heavy in the substance

Or the division of the twentieth part

Of one poor scruple—nay, if the scale do turn

But in the estimation of a hair,

Thou diest, and all thy goods are confiscate.

(4.1.319–327)

The confiscation of his goods is beside the point; Shylock’s only heir, his daughter Jessica, has already stolen what she could find in his house and run off with a Christian. It is simply his own life that he will have to sacrifice to take his revenge upon Antonio.

“Hates any man the thing he would not kill?” Shylock had asked (4.1.66). Portia now has devised a test to see how much Shylock hates Antonio, and the answer is: not enough. Not enough to go ahead and plunge the knife into his enemy’s heart, which he can do at this very moment, in the sight of all those who have mocked and despised him, provided he is willing to die for it. Faced with the demand of such absolute hatred, Shylock flinches: “Give me my principal, and let me go” (4.1.331).

This is the play’s climactic revelation about the Jew, the reason Shakespeare calls what he has written a comedy, and the source perhaps of its contemporary relevance: Shylock refuses to be a suicide bomber. Instead of pursuing hatred to its ultimate end—the longed-for annihilation of his enemy at the simple cost of self-slaughter—Shakespeare’s Jew makes a different choice: he opts for his money (“Give me my principal”) and his life (“Let me go”).

At the decisive moment of his life, the Christian Antonio, ripe for martyrdom, had asked that all attempts at further negotiation with Shylock be dropped—“I do beseech you,/Make no more offers” (4.1.79–80)—and had expressed his complete willingness to die. At his comparably decisive moment, the Jew Shylock seems to hear the words of Deuteronomy: “Therefore choose life” (30.19). But it is not so simple, as Portia quickly reveals.

Shylock wanted to stay within the embrace of the law, and the embrace now closes in upon him. Since the Jew has in effect sought to take the life of a Venetian citizen, the case has shifted from a civil to a criminal matter, and the plaintiff has become the defendant. Antonio arranges the terms that enable Shylock to escape execution: the immediate surrender of half his goods, his entire estate to go to his daughter and her husband, and his conversion to Christianity, that is, the loss of difference. And with this loss of difference, the Jew simply disappears. The play still has an entire act before it reaches its end. All that is left is comedy, tinged with melancholy and bitterness, but still officially comedy.

3.

Some years after Shakespeare wrote The Merchant of Venice he returned to the subject of hatred and tried to imagine what it would be like if the hater did not accept any limits, if he were willing to go as far as he had to go to destroy his enemy. The enemy in question, Othello, is once again an outsider in Venice, but one who has become the trusted, stalwart arm of Venetian might against the menacing Turks. Of course, as a “Moor”—the name by which Othello is repeatedly called throughout the play—he might naturally be assumed to be a Muslim: “And wheras I speak of Moores,” to quote a late sixteenth-century text, “I meane Mahomets sect.” But sometime in the course of what he calls his “story”—

Of moving accidents by flood and field,

Of hairbreadth scapes i’th’ imminent deadly breach,

Of being taken by the insolent foe

And sold to slavery; of my redemption thence

(1.3.134–137)

—Othello has evidently converted. Though he may bear the ineradicable mark of circumcision, he is now conspicuously, insistently, decisively a Christian. Yet he is by no means fully accepted, not by Brabantio, who speaks of his “sooty bosom” and warns that “Bondslaves and pagans shall our statesmen be,” not by Roderigo, who calls him “thick-lips” and speaks of the “gross clasps of a lascivious Moor,” and above all not by the play’s great hater, Iago.

Iago is not interested in justice; he does not crave the law; he desires only Othello’s utter ruin, and he will stop at nothing to bring it about. It does not matter that he is dependent on Othello, first as ensign and then as lieutenant, the position he coveted; it does not matter that his wife Emilia is the lady’s maid of Othello’s wife Desdemona. One of the ironies of Iago’s celebrated advice, “Put money in thy purse,” is that he himself is entirely uninterested in his own well-being. Hatred as intense and single-minded as his is finally indifferent to his very survival.

Near the play’s end, when Othello finally understands what he has been gulled into doing, he stares at Iago in astonishment: “Will you, I pray, demand that demi-devil,” he asks, “Why he hath thus ensnared my soul and body?” To a comparable question in The Merchant of Venice Shylock replies that he can give no reason other than “a lodged hate and a certain loathing” that he bears Antonio. In Othello Iago refuses even the minimal satisfaction that such a stripped-down declaration of motive could provide:

Demand me nothing. What you know, you know.

From this time forth I never will speak word.

(5.2.309–310)

There is no comic potential that lies on the other side of this moment, no escape to the moonlit garden in the country house. In the face of a limitless, absolute, wordless hatred lodged in an ordinary human being, the bystanders are reduced to incoherence. One of them talks about torturing Iago to open his lips and make him speak—but what is the point? The audience has heard everything Iago has to say and knows that nothing he could reveal under torture will help. Shakespeare’s comedy offered the audience a re- assuring, if uneasy, fantasy of conversion: Shylock would become one of us, and in doing so he would disappear. But there is no comparable reassurance in Othello: honest Iago’s hatred has no limits, and he is already one of us.

This Issue

September 30, 2010

-

1

In Blood Relations: Christian and Jew in The Merchant of Venice (University of Chicago Press, 2008), the late Janet Adelman, reviewing the evidence that individuals and small groups of converted Jews were living in England in Shakespeare’s lifetime, argues that they have a “shadowy” presence in his depiction of Shylock. See also James Shapiro, Shakespeare and the Jews (Columbia University Press, 1996). ↩

-

2

Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 179. ↩

-

3

Umayma Ahmad al-Jalahma (of King Faysal University in al-Dammam), “The Jewish Holiday of Purim,” al-Riyadh, March 10, 2002, quoted in “Saudi Government Daily: Jews Use Teenagers’ Blood for ‘Purim’ Pastries,” the Middle East Media Research Institute. “The Jews’ spilling human blood to prepare pastry for their holidays is a well- established fact.” For Purim, the author informs her readers, “the victim must be a mature adolescent who is…either a Christian or a Muslim. In contrast, for the Passover slaughtering,…children under ten must be used.” Following protests, there were some criticisms of al-Jalahma’s article in the Saudi press. ↩