How bad are things for the Democrats? It is generally assumed in Washington these days that in the November 2 elections the party will lose control of the House of Representatives, and possibly the Senate (although this is less likely). If the Republicans take control of one or both chambers, they and conservative commentators will proclaim that the voters have rejected “socialism” and will begin planting in earnest the idea that Barack Obama will be a one-term president.

The most damaging actual effect of such an outcome, one few people have focused on yet, is that once Republicans gain the chairmanships of House committees, they will begin launching investigation after investigation into the Obama administration, for example on charges that the Justice Department has shown racial favoritism in refusing to prosecute the New Black Panther Party of Philadelphia for alleged electoral irregularities. These will have little or no meaningful basis in fact but will attempt to distract the administration from its policy objectives, make it look dirty, and with any luck catch a big fish on the hook of perjury or obstruction of justice. (Look for the theme of “Chicago-style thuggery,” which was bandied about here and there earlier but never quite caught on outside the right-wing echo chamber, to reemerge.) The Republicans play to win.

How did things get this bad for Obama? The reasons are numerous. The condition of the economy is of course the chief one. If the stimulus had kept unemployment below 8 percent, as Christina Romer, recently departed chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers, once promised it would, in one of the least advisable public comments by any Obama administration official so far on any subject, then discontent across the land would not be so great, and the bayings of the furious Tea Party minority would likely not be resonating as they are. By all accounts, top presidential economic advisers like Timothy Geithner and Lawrence Summers (who will leave office at the end of the year) really did think the economy was going to be in recovery by now. Had they been right, the political prognosis for Democrats would consist of lost seats, but not on nearly the scale predicted today.

Some longtime observers of Congress point to history, and the fact that the president’s party almost always loses seats in midterm elections—since 1862, it has averaged losses in midterm elections of about thirty-two House seats and two Senate seats. Only twice since the Civil War—in 1934, during the Depression, and in 2002, following the September 11 attacks—has the president’s party gained seats two years after he took office. Other experts argue that the Democratic majority ballooned unnaturally in 2006 and 2008: because of George W. Bush’s unpopularity, Democrats won some seats that they ordinarily never win, so the losses of 2010 can to some degree be seen as Republicans regaining seats they had long held.

The first argument is certainly true. The second one has merit but is sometimes overstated. It is the case that the Democrats expanded their base in 2006 and 2008 into areas that were historically Republican. But they didn’t capture all of these seats solely because of Republican unpopularity. Some of these areas were changing enough demographically to make Democratic candidates more credible. In Michigan’s 7th District (west and south of Ann Arbor), Virginia’s 5th District (southwest, including Charlottesville), and New York’s 19th District (Dutchess and Rockland counties), for example, an increase in the number of college- educated professionals helped produce Democratic wins in 2006 and 2008, and wins may again be possible in those districts in the future.

In the long term, the map of competitive districts has expanded in the Democrats’ favor because of these changes, which also include more Latino voters in the Southwest (even Texas might be a Democratic state by the 2020s). But this year, the Democratic incumbents in all three of these districts—Mark Schauer, Tom Periello, and John Hall, respectively—are fighting for their political lives and expected to lose.1

Among Democrats and liberals, there is, as usual, little consensus about how matters reached this point. The standard liberal argument is that Barack Obama has failed to be liberal or populist enough on such matters as the size of the stimulus bill and the content of the health care and financial reform bills. The centrists argue that Obama has been far too liberal and should have been more concerned about the deficit. Some observers blame Obama’s efforts at bipartisanship, which they call excessive and naive, and see as rooted in a kind of messianic faith in his own presumed powers of persuasion, despite the fact that he has been faced with Republican caucuses that are dogmatically and unbudgeably determined not to collaborate with Democrats. Many have criticized the President for not going out and politicking more aggressively during the spring and summer, and trying to set the terms of debate early instead of letting the Republicans define them.

Advertisement

All of these arguments have some validity; the last one especially is difficult to challenge. With his big speeches on September 6 (Labor Day) and September 8, in which he laid out his positions on taxes, small businesses, and other issues, and in which he spoke in an unusually personal and pointed manner about the House Republican Leader John Boehner of Ohio, Obama joined the battle. But it seemed strange that it took him so long, especially after the Republicans had made so much of their intransigence and after a summer during which Democrats absorbed a number of political blows, from the collapse of any hope for energy legislation to the release of more bad jobs reports to the hideous, demagogue-driven kerfuffle over the lower Manhattan Islamic center.

There is a case to be made that November 2 might not turn out as badly for the Democrats as most pundits think. No one can say as yet just how the Tea Party movement may divide the GOP vote. But whatever happens, even if they maintain control of the House of Representatives by a slim margin and the Senate by a modest one, they must face a bleak truth. Once again, as was the case after September 11, and as has so often been the case recently in American politics, the Republicans have succeeded in branding the Democrats as not merely elitist but somehow alien and un-American, and the Democrats, from the President on down, have had almost nothing to say about it. One had thought, watching Obama’s well-run presidential campaign, in which his team responded to most attacks quickly and efficiently, that the Democrats would not let themselves be so misrepresented again. But here we are.

My own answer to the question of how things got this bad has less to do with whether Obama should have been more liberal or more centrist than with his and his party’s apparent inability, or perhaps refusal, to offer broad and convincing arguments about their central beliefs that counter those of the Republicans. This problem goes back to the Reagan years. It is a failure that many Democrats and liberals hoped Obama could change—something he seemed capable of changing during the campaign but has addressed rather poorly once in office.

In American politics, Republicans routinely speak in broad themes and tend to blur the details, while Democrats typically ignore broad themes and focus on details. Republicans, for example, speak constantly of “liberty” and “freedom” and couch practically all their initiatives—tax cuts, deregulation, and so forth—within these large categories. Democrats, on the other hand, talk more about specific programs and policies and steer clear of big themes. There is a reason for this: Republican themes, like “liberty,” are popular, while Republican policies often are not; and Democratic themes (“community,” “compassion,” “justice”) are less popular, while many specific Democratic programs—Social Security, Medicare, even (in many polls) putting a price on carbon emissions—have majority support. This is why, when all else fails, Democrats try to scare people about the threat to Social Security if the GOP takes over, as indeed they are doing right now.

What Democrats have typically not done well since Reagan’s time is connect their policies to their larger beliefs. In fact they have usually tried to hide those beliefs, or change the conversation when the subject arose. The result has been that for many years Republicans have been able to present their philosophy as somehow truly “American,” while attacking the Democratic belief system as contrary to American values. “Putting us on the road to European-style socialism,” for example, is a rhetorical line of attack that long predates Obama’s ascendance—it was employed against the Clintons’ health care plan as well.

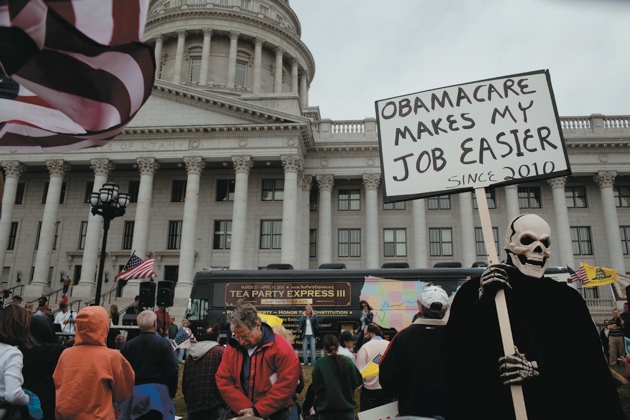

But now consider the specific problems facing Obama, a mixed-race (but visibly black) man with an exotic name and a highly atypical biography for a president. Add in also the greatest economic crisis in eight decades, and governmental responses to the crisis that, to an energized and organized right wing, seem to smack of socialism. One result is that we have a new faction, the well-financed Tea Party movement that has been able to arrogate to itself practically every symbol of Americanism and to paint the President, his ideas and policies, and his supporters as not merely un-American but actively anti-American. In a Newsweek poll released in late August, nearly a third of Americans actually agreed that it was “definitely” or “probably” true that Obama “sympathizes with the goals of Islamic fundamentalists who want to impose Islamic law around the world.”2

Advertisement

In the face of all this, it seems not to have occurred to a single prominent Democrat, from Obama on down, to say something like: We love our country every bit as much as they do, and we believe patriotism means expanding access to health care, protecting the environment, and imposing effective new rules on Wall Street. Democrats have thus crippled themselves by adapting comparatively limited ideas of legitimate political action, and by ceding to Republicans the strong claim of love of one’s country.

This is not the sort of thing that is measured by polls, but I believe the Democrats’ hesitance to tie their programs to larger beliefs has been demoralizing to liberals and confusing or off-putting to independents. The impression is left with voters that Republicans are fighting for the country, while Democrats are fighting for their special interests. The pre-presidential Obama powerfully made this kind of broad, patriotic appeal, both at his 2004 convention keynote address and in his stirring Jefferson-Jackson Day speech in Iowa in November 2007. But any sense that the Democrats are now making a coherent argument about what kind of country they want has vaporized. Underneath all the Democrats’ bickering about such issues as health care and the performance of Tim Geithner, that is their real problem.

The Congress that convenes next January, even if it remains in Democratic hands, will be markedly different from the one that met as Obama first took office. The party’s margins in both bodies—now seventy-seven in the House and eighteen in the Senate, counting the two independent senators who caucus as Democrats—will be significantly lower. Given the number of centrist and conservative Democrats who will remain but who will likely go along with the GOP, chances of passing any progressive legislation will be close to nil.

Some well-known legislators—in addition to Ted Kennedy and Robert Byrd, the last remaining links to the Senate’s better days until their deaths during this session of Congress—could well be gone. Patty Murray of Washington State, who came to the Senate in the 1992 “Year of the Woman” election after the Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas controversy, is currently in a tight race with Republican Dino Rossi, who in 2004 lost the closest gubernatorial race in US history (after having been initially declared the winner). Wisconsin’s Russ Feingold is for the time being trailing Ron Johnson, a Tea Party–backed candidate who married into and then helped build a plastics fortune and who said last month of global warming: “I think it’s far more likely that it’s just sunspot activity, or something just in the geologic eons of time where we have changes in the climate.” If Murray and Feingold both lose, the election will likely be a major defeat for Democrats.

At least seven Tea Party candidates have won Republican Senate primaries. Christine O’Donnell of Delaware has received the most attention since her surprise September 14 win over the moderate Mike Castle; but while she tries to account for her past financial and other activities, others who hold strong right-wing views are far more likely to become senators than she. In Utah, Mike Lee is virtually certain to defeat the Democratic candidate, Sam Granato. The Salt Lake Tribune, in endorsing a Lee opponent earlier this year, wrote:

To be fair, [Tim] Bridgewater’s policies are almost as radical. This is, after all, a contest between hard-right ideologues. But we sense from our discussion with Bridgewater at least a modicum of openness to the spectrum of ideas, a glimmer of a pragmatism. We can’t say that of Lee.

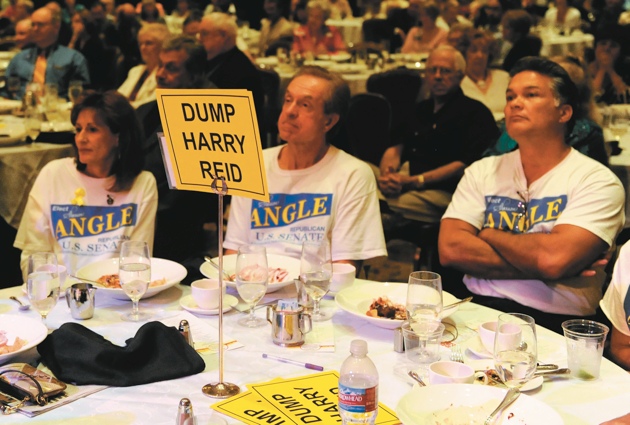

In Colorado, Ken Buck appears to be slightly ahead of Democratic incumbent Michael Bennet, who was appointed to the seat when Obama named then Senator Ken Salazar to head the Department of the Interior. Of Social Security, Buck said: “I don’t know whether it is constitutional or not.” He opposes abortion, including exceptions in cases of rape or incest. So do Christine O’Donnell and Sharron Angle of Nevada, who runs even with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and who also opposes exceptions when the mother’s life is at risk. In January, Angle was asked by a conservative talk-show host if she could envision any reason for an abortion and said, “Not in my book.”

Angle made that remark on a conservative radio show: many Tea Party candidates avoid mainstream media interviews altogether and speak to the public only through their websites, their Facebook pages, right-wing talk-radio shows, and (if they can get the air time) Fox News. They saw the trouble Kentucky’s Rand Paul—also likely to become a senator—encountered when he submitted to questions from MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, who got him so twisted around on civil rights that he had to admit that the logical extension of his opposition to federal limits on freedom of association would lead to his having opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He and other Tea Party candidates have largely avoided such situations since. Angle told the Christian Broadcasting Network that she won’t appear on nonconservative media because they won’t let her make her fund-raising pitch (“there’s no earnings for me there”).

In the House, no well-known Democratic members are likely to lose. In California, for example, the seat of Henry Waxman is quite safe. But the Democrats are likely to absorb losses of territory that will hurt. Since 1969, David Obey, an outspoken liberal, has represented Wisconsin’s 7th District, bordering Minnesota north of the Twin Cities. That district, according to the political analyst Nate Silver, is almost certain to go Republican. Democratic losses are likely in Indiana, Colorado, Arizona, Washington, West Virginia, New Mexico, and several other states.

There don’t seem to be precise figures on how many Republican House candidates are endorsed by Tea Party groups, because there are many such groups and because media coverage has often pinned the label on insurgent candidates even if they lacked explicit backing. What is particularly worth attention is that a large number of GOP House candidates have pledged to back a key Tea Party demand: that the federal government balance its budget every year. This is both radical and chimerical—the sainted Reagan ran deficits in six of his eight presidential years. The demand is, not so secretly, an attack on the entitlements of Social Security and Medicare, since they make up about 40 percent of federal spending and since the real goal of many conservatives is to get the government out of the pension and health businesses.

The candidates supporting these positions, it is worth noting, will be backed by perhaps unprecedented amounts of corporate dollars. Corporations are now able to spend as freely as they wish as a result of the January Citizens United Supreme Court decision.3 Experts say that large, publicly traded companies have so far not seemed to change their giving habits, but smaller, privately held companies “are jumping in, mainly on the Republican side.”4 In February, the Center for Responsive Politics estimated that more than $3.7 billion would be spent in this year’s midterms, a 30 percent increase over 2006—and that was without taking the effects of the Citizens United decision into account.5

In a morbid sort of way, it will be fascinating to see what will happen in a Congress populated by so many people keen to join it because they despise it. Whatever emerges, one thing is not in doubt: if the Republicans win the House, they will launch a series of investigations into the Obama administration, quite possibly leading to another impeachment drama.

This is not often discussed, but it is certainly no secret. Politico reported in late August:

Everything from the microscopic—the New Black Panther party—to the massive—think bailouts—is on the GOP to-do list, according to a half-dozen Republican aides interviewed by POLITICO.

Republican staffers say there won’t be any self-destructive witch hunts, but they clearly are relishing the prospect of extracting information from an administration that touts transparency.

And a handful of aggressive would-be committee chairmen—led by Reps. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) and Lamar Smith (R-Texas)—are quietly gearing up for a possible season of subpoenas not seen since the Clinton wars of the late 1990s.6

Minnesota Representative Michelle Bachmann, who often speaks as the unrestrained id of this new right, said, when asked how Republicans should wield their subpoena power: “Oh, I think that’s all we should do. I think that all we should do is issue subpoenas and have one hearing after another.”

Republicans would deny that impeachment is ultimately on their minds. But why wouldn’t it be? They have shown repeatedly that they play to their base, and much of their base already believes that Obama is probably not an American citizen and therefore is an illegitimate president. In a Harris Poll from March, 24 percent of Republicans even agreed that Obama “may be the Antichrist.” When your most loyal voters think that, not trying to remove the man from office would amount to malpractice. If the Democrats are worried about the much-discussed “enthusiasm gap” between Republicans’ voters and theirs, perhaps bringing these issues out of the shadows would help close it.

In the third week of September, some new polls emerged showing more favorable results for Democrats. Obama’s own approval ratings appeared to have stabilized, and in fact given the unemployment rate they aren’t so bad—better than Reagan’s at a similar juncture. And Republicans still poll worse than Democrats on most major issues.

Much momentum may be gained or lost according to which party is seen, by Election Day, as having won the battle over the renewal of the Bush tax cuts. Those cuts were passed in 2001 under “reconciliation” rules requiring that they expire after ten years, with rates returning to 2000 levels. Obama and most Democrats support extending the cuts for households earning under $250,000 per year but ending them for the upper brackets. Republicans want to make all the cuts permanent. Recent polling indicates that majorities back the Democratic view—53 to 38 percent, for example, in a mid-September New York Times/CBS survey.

Obama and the Democratic leaders had hoped to force a vote in both houses of Congress that would have put the Republicans on the spot. They wanted to hold votes on the middle-class cuts only, forcing the Republicans to declare whether they were willing to block middle-class tax relief because the top 2 percent of households were not included. This should have been an easy win for the Democrats. But a number of Democrats in both houses actually supported the Republican position, and even some Democrats who didn’t go quite that far nevertheless feared that such a vote would make them vulnerable to attacks ads charging that they were tax raisers. And so the voting on taxes was put on ice until after the election.

Some Democrats try to argue that the issue has already received so much attention that the Republicans’ position was widely known and would hurt them. A Senate aide told Talking Points Memo on September 23: “We have a winning message now, why muddy it up with a failed vote, because, of course, Republicans are going to block everything.” This sounds like a highly wishful rationalization. Perhaps Obama and Democrats can still campaign on the issue, but even a failed vote would have put the matter in starker relief before voters.7

Of course, one might argue, as a matter of economic policy, that more tax cuts aren’t what we need. Lost for the most part in the debate over whether the wealthiest Americans can bear to go back to paying 39.6 percent rather than 35 percent on all income over $250,000 is the fact that from 1950 to 1963, back when we were building a vast middle class and a society in which Democratic themes like “community” weren’t considered toxic, the top marginal rate on very-high-income earners, a rate that majorities of both parties supported, was just over 90 percent. In reality, there were ways of avoiding that rate, and those days will probably never return. But as long as Democrats permit Republicans to appear to be defending (and defining) what it is to be American, matters like that 4.5 difference will be attacked as un-American class warfare, and the attacks will resonate even more loudly from the perches of House committee chairmanships. n

—September 30, 2010

This Issue

October 28, 2010

-

1

Nate Silver, whose fivethirtyeight.com won a wide and obsessive following in 2008, now publishes his blog at The New York Times, where he forecasts the likelihood of outcomes for every House, Senate, and gubernatorial race in the country. See fivethirtyeight .blogs.nytimes.com. ↩

-

2

Results by party affiliation showed that 52 percent of Republicans believed this, while 27 percent of independents did, and even 17 percent of Democrats. See nw-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/pdf/ 1004-ftop.pdf, question 24. ↩

-

3

See the articles by Ronald Dworkin in these pages: “[The ‘Devastating’ Decision](/articles/archives/2010/feb/25/the-devastating-decision/),” February 25, 2010, and “[The Decision That Threatens Democracy](/articles/archives/2010/may/13/decision-threatens-democracy/),” May 13, 2010. ↩

-

4

See Michael Luo and Stephanie Strom, “Donor Names Remain Secret as Rules Shift,” The New York Times, September 21, 2010. ↩

-

5

See “Midterm Elections Will Cost at Least $3.7 Billion,” Open Secrets blog, February 23, 2010. ↩

-

6

See Glenn Thrush, “GOP Plans Wave of White House Probes,” Politico, August 27, 2010. ↩

-

7

Christina Bellantoni and Brian Beutler, “Senate Dems Ready to Shelve Tax Cut Vote,” www.talkingpointsmemo .com, September 23, 2010. ↩