In 1916, John Buchan published his best-selling thriller Greenmantle, which imagined a German plot to rouse the eastern legions of Islam against the embattled British Empire and its hundred million Muslim subjects. The book lightened the captive hours of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia before his 1918 murder by the Bolsheviks.

At the time Buchan wrote his adventure yarn, he was serving as director of information for the British government and thus had access to some privileged intelligence. But there is no evidence from his autobiography or biographers that he knew how strongly his fantasy was rooted in reality. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany enjoyed a personal romance with Islam, intensified by national strategic imperatives.

Sean McMeekin, who teaches international relations at Turkey’s Bilkent University, has written the story, unfamiliar to most Western readers (though Hew Strachan addresses it well in his magisterial history of World War I1), of how Germany and its agents played the Great Game with the Ottoman Empire and in Muslim lands beyond its frontiers. In 1914–1915, they strove to mobilize Islam against the Allies in just the fashion Buchan suggested. “There is concrete evidence,” writes McMeekin, “that Turco-German-jihad action plans were ready to go when the guns of August started firing.”

The Kaiser’s Islamic enthusiasm was fired by an 1889 visit to Turkey, which Bismarck opposed on the grounds that it would gratuitously alarm the Russians. Wilhelm met the murderous Sultan Abdul Hamid II and enjoyed the sinuous gyrations of the Circassian dancers in his Constantinople harem. In 1898 Wilhelm returned to the Ottoman Empire and rode into Jerusalem through a breach specially made in its walls, allegedly to dedicate the new Church of the Redeemer, built by German Protestants.

This pilgrimage was deemed somewhat less benign than it sounded, since the Kaiser wore a field marshal’s uniform with holstered pistol. Moreover, his sentiments were notably unchristian. “My personal feeling in leaving the holy city,” he wrote to his cousin the Tsar, “was that I felt profoundly ashamed before the Moslems and that if I had come there without any Religion at all I certainly would have turned Mahommetan!” McMeekin: “Thus was born Hajji Wilhelm, the mythical Muslim Emperor of Germany.”

The Kaiser and some influential German diplomats, bankers, and soldiers were powerfully attracted by the notion of establishing a bridgehead in the Near East to exploit its natural resources. The foremost manifestation of German influence would be a railway built from the Asian shore of Constantinople to Baghdad, crossing not only Turkey’s vast wildernesses but the Taurus Mountains and bandit regions of Syria and Mesopotamia.

Wilhelm’s ambassador to the Ottoman court, Baron Marschall von Bieberstein, wrote that the railway must be constructed “with only German materials and for the purpose of bringing goods and people to [Asia]…from the heart of Germany.” The Ottoman Empire was bankrupt, but this did not deter German investors, who provided two thirds of the colossal sum needed to start construction in 1903. The Germans were rewarded with mineral exploration privileges for some twelve miles on either side of the tracks, and with the right to keep all artifacts found by their archaeologists in the country, which yielded rich dividends to Berlin’s museums in the years that followed.

The project provoked predictable foreign alarm. A St. Petersburg newspaper declared that when the railway was completed, “Turkey will be completely subjected to German economic control.” French intelligence assumed that the scheme had been hatched by the German General Staff, and Downing Street expressed concern. But it was the bankers who had cause for lamentation. In 1905, exhaustion of resources stopped work after the track had advanced a mere 120 miles from Constantinople, to an obscure halt named Bulgurlu where travelers were invited to transfer to camel caravans for the journey across the Taurus.

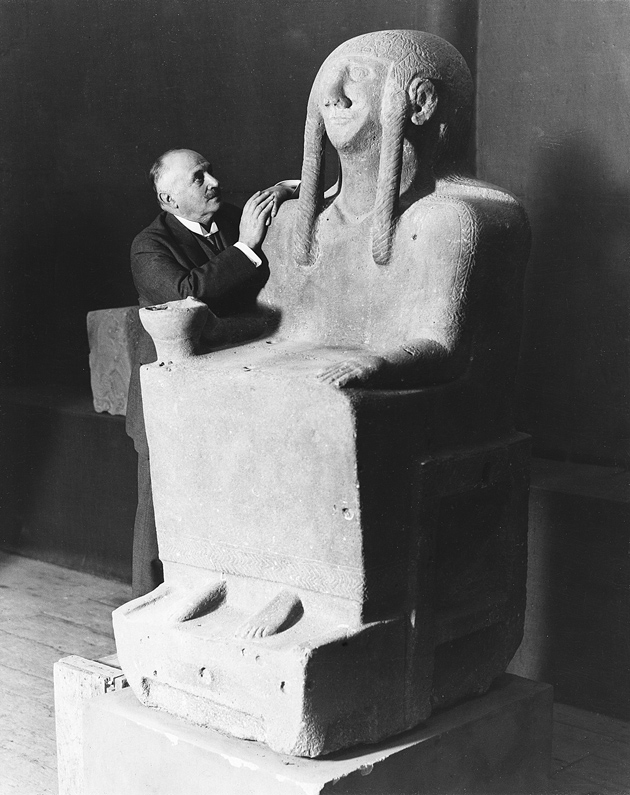

The signing of the Triple Entente between Britain, France, and Russia in 1907 inspired a new surge of German enthusiasm for the rail project. Foremost among the zealots was an exotic figure named Max von Oppenheim, a scion of the Jewish banking family, though his father had converted to Catholicism. Von Oppenheim, born in 1860, was a former guards officer who fell in love with the East and spent much of his life there. He assembled a collection of 150 Muslim women’s costumes and often affected local garb. He conducted a shootout with bandits in the Rif Mountains (they dispersed after his five bullets pierced their five water bottles) and established a personal harem in Cairo in which his principal concubine was changed annually.

If von Oppenheim was a considerable charlatan, he impressed T.E. Lawrence, another Arabist of whom McMeekin also thinks poorly. Lawrence described the German’s work From the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf (1889) as “the best book on the area I know.” The Kaiser agreed. He was strongly attracted by von Oppenheim’s passion for the creation of a Pan-Islamic front against Britain and often met with him. Another such enthusiast was a serious young Orientalist, Curt Prüfer, who came to hate the British after they vetoed his appointment as director of the Khedivial Library in Cairo. Like von Oppenheim, Prüfer affected Arab dress among the Bedouin.

Advertisement

In 1907, upheavals descended on Turkey that changed almost everything. An army mutiny and demonstrations in the streets prompted the eclipse of Sultan Abdul, the reinstatement of the constitution, and the summoning of parliamentary elections in July 1908. The prime movers were Young Turk revolutionaries of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) party, secularists who spurned the sultan’s Pan-Islamist pretensions. Some were strong admirers of liberal Britain, notable among them Ahmed Riza, known as “English Ali” because of his fluency in the language. As an exile in Paris, he wrote to his sister:

Were I a woman, I would embrace atheism and never become a Muslim. Imagine a religion that imposes laws always beneficial to men but hazardous to women such as permitting my husband to have three additional wives and as many concubines as he wishes, houris awaiting him in heaven, while I cover my head and face as a miller’s horse…. Keep this religion far away from me.

Ahmed Riza achieved prominence in Turkey’s government, but renewed turbulence unseated him. The CUP government was blamed for the Ottoman Empire’s loss of Bosnia and Bulgaria in October 1908. The following April, mobs stormed the parliament building demanding the restoration of Sultan Abdul and the introduction of sharia law. Ahmed Riza, his brief hour ended, was obliged to seek refuge in a German railway company building.

On April 24, however, the army staged a counter-counterrevolution. The sultan was deposed, this time for good, and replaced by the figurehead Mehmed Reshad V. A new government was dominated by Young Turks. The Germans in Constantinople, panting to keep pace with these bewildering changes, received decisive assistance from an unexpected quarter.

The British ambassador, Sir Gerard Lowther, responded to the rise of the new secularist modernizers with lofty disdain. His dragoman, Gerald Fitzmaurice, a violent anti-Semite, described the new finance minister, Djavid Bey, as a “Crypto-Jew…[at] the apex of Freemasonry in Turkey” and likened the revolutionaries to French Jacobins. Britain resisted the new government’s advances. German influence became powerfully resurgent because the Turks saw nowhere else to turn.

In 1910, the Baghdad railway project was revived with a new loan of 160 million francs from Deutsche Bank. Krupp began to supply arms to Turkey, heedless of the slender prospects that these would ever be paid for. German power could do nothing to prevent the severe reverses that fell upon the Ottoman Empire in the years that followed, with Italy’s seizure of Libya in 1911 and the loss of four fifths of its European territories—Macedonia, Albania, and Thrace—to the Balkan League in 1912–1913. But the Germans were much excited by the waves of passion and anger that swept the Muslim world, including British India, in the face of these blows to the Caliphate.

Eighteen rioters were killed by police in Cawnpore in India in August 1913. The German consul general in Calcutta reported to Berlin that year, as Balkan armies threatened the ancient Ottoman capital of Adrianople:

A thousand channels flow from here to Constantinople, and if the inheritance of the prophet [i.e., the Caliphate] were in strong hands it could bring forth apparitions, which could seriously shake the equilibrium of this land [India].

The onset of European war in August 1914 made the allegiance of Turkey seem an important prize, above all because the Dardanelles controlled western access to Russia through the Black Sea. Baron Max von Oppenheim now had his hour as “the prophet of global jihad.” In Berlin, he was appointed to lead an Islamic propaganda bureau and began recruiting agents. McMeekin writes: “Germany’s leaders saw in Islam the secret weapon which would decide the world war.” Helmuth von Moltke, chief of the General Staff, instructed the German foreign office that “revolution in India and Egypt, and also in the Caucasus, is of the highest importance.”

The Germans achieved a notable propaganda coup when they dispatched the cruisers Goeben and Breslau through the Mediterranean, evading the Royal Navy, to reach Constantinople where they were presented to Turkey as a substitute for two dreadnoughts under construction in Britain for Turkey, and now appropriated by First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, to the fury of the Turkish people.

While the world waited to see which way the Turkish government would jump, German officers worked with their Turkish counterparts to plan an assault on Suez. A group of prominent German Arabists assisted the Berlin government in drafting a policy paper entitled “Overview of Revolutionary Activity We Will Undertake in the Islamic-Israelite World.” This proposed that Germany should sponsor both an anti-British jihad in the East and an Israelite-cum-Zionist rebellion in Russia. It is striking that, in World War I, Germany’s rulers flirted with the notion of publicly espousing Zionism as an aid to their cause.

Advertisement

Germany’s international prestige rose steeply following its victory over the Russians at Tannenburg in East Prussia at the end of August 1914. The German ambassador in Constantinople reported that Sherif Hussein of Mecca was eager to fight the British—or at least to be on the war’s winning side. The diplomat asserted that Enver Pasha, prime mover in the Young Turk government, “fears only that the war will be over before the various rebellions [in Entente countries and dependencies] break out, the preparations for which will take several months.”

Max Roloff-Breslau, an Islamic scholar who had lived in Dutch Indo- nesia, was dispatched in Arab disguise on a mission to Mecca, though it is uncertain whether he ever got there. The Bavarian officer Oskar von Niedermayer, who had traveled extensively in the East, was dispatched with a large mission to Persia and Afghanistan through neutral Romania. This was disguised as a traveling circus. Unfortunately its cover was blown when an alert Romanian customs officer noticed wireless aerials protruding from baggage labeled as tent poles. Large bribes had to be paid before the mission proceeded on its journey, which became an epic of privations and frustrations.

Yet another officer, Karl Emil Schabinger von Schowingen, recruited some Muslim prisoners of war, draftees from France’s African colonies, who set off for Turkey via Romania. With startling unoriginality, they too masqueraded as acrobats in a traveling circus, though Schabinger rather spoiled the effect by himself traveling first-class while his performers were crowded into third. On arrival in Turkey, they were coached to play the parts of jihadi fanatics, then let loose on the streets of Pera to loot and burn French- and English-owned shops. Schabinger himself proceeded to the most expensive hotel in town, the Tokatlian, where his Turkish police escort fired a symbolic revolver bullet into the English grandfather clock in the lobby.

Turkey was still neutral, but it was increasingly obvious that Enver Pasha and his comrades intended to fight. On October 27, Germany’s Admiral Wilhelm Souchon took action designed to hasten such an outcome. He led the nominally Turkish Goeben and Breslau in an assault on Russian shipping in the Black Sea, which caused havoc. On November 2, St. Petersburg responded by declaring war on Turkey. On the 14th, Sultan-Caliph Mehmed Reshad participated in a solemn ceremony at the Fatih Sultan Mehmed mosque in Constantinople, where he took up the sword of the Prophet to sanctify war against Britain, France, and Russia.

McMeekin writes that he thus “inaugurated the first ever global jihad, in which it would be the duty of Muslims everywhere on earth to wage war on [Entente] infidels.” Next day a solemn holy war procession was held in Damascus. German agents began to distribute in many languages throughout the Middle East a mass of jihadi literature drafted by Max von Oppenheim’s bureau, pronouncing a sentence of death on European infidels: “Take them and kill them whenever you come across them.” Efforts were launched to persuade the Sanussi tribes of Italian Libya to invade British Egypt.

Long before Lawrence reached Arabia in 1917, Germany’s Leo Frobenius was on his way from Berlin to Somalia and Abyssinia to stir up jihad. A caricature of Prussian haughtiness, Frobenius took two weeks to travel from Constantinople to the Hejaz, scarcely a tribute to the progress of the Berlin–Baghdad railway. There he found another Wilhelmite agent, one Professor Bernhard Moritz, with whom he promptly quarreled, causing Moritz to decamp toward Sudan.

Thereafter, Frobenius set off down the Red Sea in a dhow, rousing Arab sentiment against the Allies as best he could. He reported exuberantly to Berlin that the Arab tribes of Sudan “await the arrival of the green flag that I am carrying, having smuggled it through [neutral Italian] customs unseen.” He dispatched several sabotage missions against British installations and made a great deal of noise. Unfortunately, it was the wrong kind. In February 1915, the first Turkish offensive against Suez was easily repulsed by the British, lifting their regional prestige. Turks, Arabs, and neutral powers alike agreed on disliking the stiff Prussian Frobenius. He was ignominiously deported from Italian Eritrea in March 1915 and shipped home, having done considerable damage to his nation’s cause.

Yet another aspiring protagonist of jihad was the great Arabist Alois Musil, a devout Catholic and subject of the Hapsburgs. Musil published a book in August 1914, Turkey and the European War, predicting Turkey’s doom if the country was foolish enough to enter the conflict. English gold and propaganda, he anticipated correctly, would mobilize the Arab tribes against the Ottoman Empire. But Musil loyally volunteered to attempt to reconcile the Arab tribes to their Turkish overlords and set out from Damascus for the desert in December 1914. Thereafter, he produced shrewd and vivid intelligence reports on the serpentine intrigues of the tribes, but contributed little or nothing to deciding their allegiances in the war.

The German jihadis in World War I fell prey to delusions that afflicted the Allies in World War II about the prospective influence of irregular forces on outcomes that were, in reality, determined by economics and the battlefield clashes of vast armies. The behavior of the world’s Muslims was influenced by their perceptions of who was likely to win, and who paid the most. McMeekin writes:

Baron Oppenheim aside,…Arab charm was generally lost on the Germans. Unlike Lawrence, field agents like Musil…were fluent enough in Arabic to understand Bedouin culture as it existed on the plane of reality, rather than in the romantic Oxbridge imagination…. Far from being loyal to the cause of Islamic holy war, Arab irregulars attacked whomever they felt like, generally those offering possibilities for plunder and who were least able to resist.

German agents promised the Arabs, the Shah of Persia, and others much in the way of gold and arms, but were able to deliver little. The emir of Afghanistan, who received £400,000 a year from the British, agreed to a secret treaty whereby he sold himself to the Germans for £10 million—the equivalent of $5 billion in modern money—but the cash was never paid.

One of Berlin’s most egregious mistakes was its decision dramatically to accelerate investment and effort in the Baghdad railway in the midst of the struggle. Vast resources were lavished on blasting a path through the Taurus Mountains. In April 1915, an Armenian uprising against the Turks in eastern Anatolia—possibly assisted by the Russians—prompted ghastly reprisals, wholesale deportations of the Armenian people to Syria, Arabia, and Mesopotamia, and deaths variously estimated between 500,000 and two million.

The Germans furiously protested the deportations. Striking an attitude presaging that of some of Hitler’s lieutenants toward the slaughter of the Jews almost thirty years later, their objections were not humanitarian but brutally pragmatic. They complained that removal of Armenian skilled workers was crippling work on their cherished railway. The Turks proved indifferent to German pleas: they were overwhelmingly preoccupied with removing a perceived strategic threat to their lines of communication with Syria and Arabia. The railway languished and Armenians continued to be massacred. Though the Allies suffered a humiliating repulse in their 1915 attempt to seize Gallipoli and a British defeat at Kut in Mesopotamia, thereafter the Turks were relentlessly driven back.

Sherif Hussein of Mecca, having frequently protested his loyalty to the Caliphate in Constantinople, suddenly reversed his position in June 1916 and launched his tribes against the Turks. The military accomplishments of this “Arab Revolt” were negligible, says McMeekin, even after it had the assistance of T.E. Lawrence in 1917, and he is surely right. He highlights the irony that Hussein justified his rebellion by denouncing the Turkish government’s secularism and enthusiasm for rights for women.

When Curt Prüfer heard news of the Arab uprising, he wrote in his diary: “Poor Oppenheim.” The failure of the German jihad thus became explicit. As the Muslim world became increasingly convinced that the Central Powers would lose the war, Germans became so unpopular that as early as January 1916 their ambassador in Constantinople felt obliged to warn the Kaiser’s subjects against traveling in the Ottoman Empire.

The hapless Oskar von Niedermayer, who had endured extraordinary hardships and disappointments on his long mission to the emir of Afghanistan, left Kabul in May 1916. In Persia, he was abandoned in the desert by his Turcoman escort, robbed, beaten, and “left dying of thirst and starvation.” The tough Bavarian eventually reached Berlin after staggering into Baghdad on foot, having begged his way west.

Baghdad fell to a British imperial army in March 1917. But that year’s Russian Revolution rekindled Turkish hopes—and also German aspirations. Germany desperately needed the oil of Baku. One of the least-known campaigns of the war was that waged by the Turks against the Russians and a small British army in the Caucasus during the late summer of 1918. The Turks took Baku on September 15, after massacring nine thousand local Armenians, but it availed them nothing amid collapse elsewhere. A few weeks later, they were obliged to evacuate the city after signing an armistice with the Allies at the Greek port of Mudros. The German railway from Constantinople to Baghdad was almost complete, but its purposes lay in ashes.

Sean McMeekin’s account possesses the large merit that it tells a story little known to Western readers, drawing extensively upon German sources. It depicts a splendid cast of characters heroic in their endeavors if absurd in their lack of accomplishments. It is hard, however, to avoid irritation with McMeekin’s casual prose: the constant use of phrases such as “flip side,” “enough Arabic to jabber a bit with the locals.” Clichés appear all too frequently: “Too many cooks [are]…threatening to spoil the broth,” there is “a giant elephant in the room,” and “no such thing as a free lunch.” Such lapses provide testimony to the flagging influence of publishers’ editors on authors’ typescripts.

McMeekin concludes by describing Baron von Oppenheim’s grotesque later career as a stooge of the Nazis who in 1939 sought to exploit the virulent anti-Semitism of the Mufti of Jerusalem. The veteran Arabist was no more successful in aiding Hitler, however, than he had been in promoting the interests of Wilhelm II. “Max von Oppenheim and his foolish Emperor,” he writes,

spent their civilizational inheritance promoting an atavistic version of pan-Islam devoted to the destruction of that civilization and to the murder of the Christians and Jews who had forged it. It was a breathtaking error in judgement, and we are all living with the consequences today.

It seems unconvincing to assert that Kaiser Wilhelm II can be held responsible for the West’s modern difficulties with the Muslim world. All the Western powers behaved ignobly as well as foolishly in handling the inescapable complexities of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The Turks were architects of their own undoing when they joined a great conflict that their nation was too weak and divided to win. They learned the appropriate lesson by wisely staying out of World War II. The Berlin–Baghdad Express is best enjoyed as a picaresque tale that John Buchan himself would have relished, though the carnage it records translates a comedy into a great tragedy. The British played the Great Game more successfully than the Germans, not because they had T.E. Lawrence but because they had deeper pockets and played a stronger hand.

This Issue

December 9, 2010