In 1981, while teaching a class in the Experimental Theatre Wing of New York University, Spalding Gray asked his students to walk twice around the block and report what they saw. Listening to their stories, he began to panic:

Slowly it dawned on me that they saw what I saw and that we are all alike and that I’ve had some investment in being special and now I have to face the fear and realization that I am basically like all the rest; a lost confused human being….

Here we have one of the many contradictions that guided Gray’s life and work: extreme narcissism paired with crippling insecurity. When Gray wrote this diary entry it was still two years before he began performing Swimming to Cambodia, the monologue that would bring him a devoted international following, moderate wealth, and appearances on David Letterman and The Nanny. But by 1981 he had already experienced some success, having written and performed, throughout the United States and abroad, ten one-man productions. In the process he had introduced a new dramatic form to modern theater: the confessional monologue.

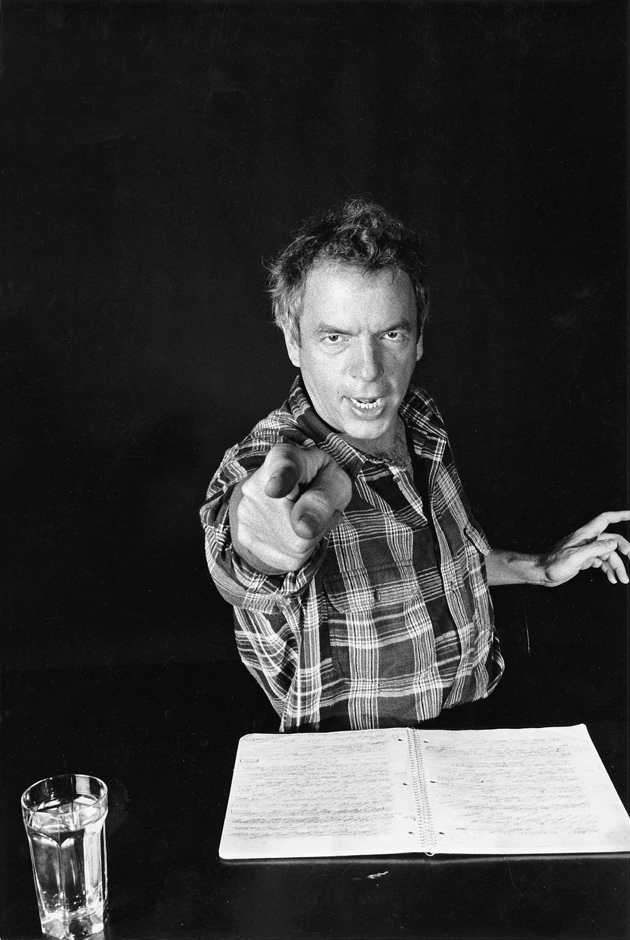

In his first monologue Gray sat at a desk, facing the audience, with a glass of water and a spiral-bound notebook. For eighty minutes he told the audience everything he could remember about his childhood experiences with sex and death. He called it Sex and Death to the Age 14. This was followed by Booze, Cars, and College Girls, which might as well have been called “Sex and Death Between the Ages of 15 and 22.” For the rest of his life he remained loyal to this approach: desk, water, notebook, sex, and death. When Gray delivered his first monologue in 1979 at the age of thirty-seven, his stories began as memories of a relatively distant past. But as the monologues proliferated, he ran out of past. Late in his career, past tense gave way to present, and the monologues increasingly came to be seen by his audience as a live play-by-play: what’s new with Spalding on the sex and death fronts. In his final piece, life at last caught up to work: the composition of Life Interrupted was itself interrupted by his suicide in 2004, at the age of sixty-two.

Gray lived a life that was unusual in many ways, but it was neither shocking nor exemplary. He was a lost confused human being, like all the rest. So how did he manage to speak for so many? And why, seven years after his death, do his monologues retain their power—a power that, were Gray not such a dogged atheist, could best be described as spiritual?

In the preface to Sex and Death to Age 14, a collection of six early monologues, Gray seemed to suggest that the answers to these questions might be found in his private journals:

The performances became my public autobiography and my private thoughts went into diary form. I felt the diary might be a way of taking full responsibility for my life, and also a more therapeutic way of splitting off a part of my self to observe another part. It was the development of a writer’s consciousness. I tried to write mainly about detail of fact and action, rather than emotions.

His journals therefore seemed to hold great promise. They would reveal how Gray transformed the raw facts of his life into dramatic incantation—how life became art. Unfortunately the biggest surprise of The Journals of Spalding Gray, now published for the first time, is how far they fall short of his intentions. As it turns out, they are exceedingly light on fact and action, while heavy on emotions. Even more frustrating, Gray neglected his journals at exactly the moments when his life was busiest. He doesn’t mention Swimming to Cambodia, for instance, until he had been performing it for eighteen months.

The journals’ editor, Nell Casey, mindful of this deficiency, has filled the breach with detailed biographical chapters, drawing from research and interviews with friends and family. She begins twenty-six years before the first journal entry, at the source of Gray’s great psychological trauma: his relationship with his mother, Margaret Elizabeth Horton. A devoted Christian Scientist in Barrington, Rhode Island, Horton believed that illness was caused by negative thinking. As a result, says Gray, “We were always afraid of being afraid.”

Sex and Death begins with a memory of the family’s cocker spaniel taking a chunk from Gray’s wrist “like a bite out of an apple.” When he runs to his mother crying, she replies, “You had it coming to you, dear, for harassing the dog with a rubber submarine.” At fourteen, Gray passed out next to his radiator; he woke to find that his arm had a “dripping-rare-red roast beef, third-degree burn.” His mother, sitting in front of the television, barely glanced up from Gunsmoke. “Put some soap on it, dear, and know the truth.”

Advertisement

“That is enormous distance,” Gray later told an interviewer. “Any mother, I don’t care what religion she’s in—I would think her intuition would be to fly to that child.”

After suffering a nervous breakdown Margaret Horton paced incessantly through the living room, repeating a religious mantra (“God is all loving and I’m His perfect reflection”), while she pulled the hair out of the back of her head. But nobody in the family, including her grimly taciturn husband, acknowledged her condition. It was, as Gray put it, like living with a ghost. Her “alternating currents” of neediness and coldness would haunt his every romantic relationship, his work, and his sense of self. She would even haunt his death.

In Monster in a Box, the monologue that confronts most directly, and most painfully, their relationship, Gray recalls a memory from the summer of 1965, after she had suffered her final nervous breakdown. He is lying beside her on the couch at the family home, reading aloud Alan Watts’s Psychotherapy East and West, “laboring under that romantic R.D. Laing idea that was so popular then that everyone who has a nervous breakdown is so lucky, because they get to come out at the other side with such great wisdom.” It was a warm July day:

And she had the Christian Science Monitor between us, like a Japanese paper wall. And I got so annoyed at not being able to get through, I just reached down and popped the paper with my finger.

And she pulled the paper down and looked me right in the eyes and said, “How shall I do it, dear? How shall I do it? Shall I do it in the garage with the car?”

She did it in the garage with the car two summers later. At the time Gray was traveling in Mexico. In his diary he describes learning of the suicide from his father when he returns home to Barrington:

have been told that my mother has killed herself my father asked me to pick up her ashes at the post office tomorrow—“a box,” he said, “Would you pick it up, because it’s probably your mother.”

His mother, it appears, was not the only Gray to adopt “enormous distance” as a parenting strategy.

A straight line can be drawn between the trauma of Horton’s suicide and Gray’s decision to perform monologues. Not long after the suicide he moved to New York, where he began acting in the experimental theater scene—first in Richard Schechner’s Performance Group, and then, with his girlfriend Elizabeth LeCompte, as a founding member of the Wooster Group. In 1975 he wrote and starred in an autobiographical trilogy, Three Places in Rhode Island. The second play, Rumstick Road, incorporated recordings of Gray’s family discussing his mother’s suicide. The third, Nayatt School, began with a short introductory monologue by Gray, speaking as himself, at a long table. That gave him the idea for Sex and Death.

It was evident from the start that Gray was, intuitively, a gifted writer. From his first monologues he showed a mastery of the essential elements of good storytelling: humor, surprise, vivid detail. Take, for instance, this anecdote from Booze, Cars, and College Girls:

This was during the Cuban missile crisis, when, after Kennedy’s speech, all the Emerson College girls ran out of the dorms, screaming, “Take me. I don’t want to die a virgin! Please, take me!” After that I kept having obsessive fantasies about how I would go to the girl’s dorm all dressed in white lace, with three eunuch slaves carrying bull whips.

The screaming girls running out of their dorms are amusing, but it’s the white lace and the eunuch slaves that make it funny. And it’s the bull whips that scorch the image in the listener’s brain.

Most of Gray’s monologues have now been published as books, and in this form they are almost indistinguishable from memoirs. But Gray never wrote down his monologues before performing them. He began by making an outline in a notebook, using his notes as prompts. Each night, he recorded the performance and made adjustments in the outline: “It wasn’t as though I was having new memories as much as remembering things I had long forgotten.” The audience served as his editor, their responses telling him where to cut, expand, pause for effect. Gray was an excellent listener—in his monologues he frequently recalls conversations with strangers, the more eccentric the better, listening patiently to their life stories and personal philosophies. During performances he listened to his audience too, estimating their approval. In a journal entry from the late Seventies he makes the connection explicit: “PARENT=AUDIENCE.”

Advertisement

In this way Gray produced his first ten monologues, most of which were narratives told in chronological order, albeit with frequent digressions. He told stories about his acting experiences (A Personal History of the American Theater); a cross-country road trip (Nobody Wanted to Sit Behind a Desk); an ill-advised decision to buy a cabin in the Catskills (Terrors of Pleasure: The House). But while the subjects varied, one element remained constant. There was always a haunting subtext—what Francine Prose, in her foreword to Life Interrupted, calls the “bass-note thrum” of death.

He recorded his fears more explicitly in the Journals, the first entry of which, written at the age of twenty-five, is a reflection on suicide. “I know that there’s a part of me so in love with death that I feel like I have already died and am looking at the living,” he wrote later, in 1976. And in 1981 Gray described the central themes of his work as:

My constant fear of death. My wanting to hold things still so I can look at them forever. Not to be a part of this body that is growing old but somewhere in me seeking eternal life…. Wanting to overcome death. Suicide is power over death in that you do it.

But Gray experienced a rebirth in 1983. He developed a two-part monologue about his experience playing a supporting role in The Killing Fields, a film about a pair of journalists in Cambodia during the reign of the Khmer Rouge. Collaborating with Renée Shafransky, Gray’s eventual first wife and the reluctant heroine of most of his monologues, his technique grew more sophisticated. While Swimming to Cambodia is unmistakably a self-portrait, his perspective is far more nuanced and complex than ever before. This is because for the first time he has a subject—the Cambodian genocide—that dwarfs in scope the neurotic crises that dominated his earlier work. (At eight minutes, Gray’s history lesson about the Vietnam War is easily the longest he had ever gone in a monologue without talking about himself.) But his storytelling also became more refined. The narrative proceeds thematically rather than chronologically, as Gray moves fluidly from the killing fields to a field in the Hamptons:

It was filled with beautiful couples all on the verge of breaking up, and lonely singles who had just broken up and didn’t feel ready to re- commit just yet. They were all playing volleyball on the front lawn and toking up in between games, and I couldn’t believe the ball just didn’t turn into a seagull and swoop out over the horizon.

Here Gray moves from the literal to the figurative, his stories assuming a fabulistic, quasi-mythical quality. He employs a kind of nightmare logic, where familiar images morph, as through a kaleidoscope lens, into surreal visions. At one point, while imagining a happy future with Shafransky (beautiful children, wealth, surfing), his fantasy is abruptly disrupted by a mental “image of MX missiles flying low over pine trees.” A similar disjunction occurs in a scene at a Bangkok brothel when, at the end of the night, the fluorescent lights turn on, and Gray’s erotic reverie is ruined by the sudden sight of the bruises, “like rotten fruit,” on the young prostitutes’ legs.

He sustained this approach through the next two monologues, both of which, like Swimming to Cambodia, were adapted into films. Monster in a Box, Gray explains at the beginning, is “a monologue about a man who can’t write a book about a man who can’t take a vacation.” The book—which sits next to Gray on stage in a giant box—is a 1,900-page autobiographical novel about his mother’s suicide. (It was later published, at 228 pages, as Impossible Vacation, and dedicated to his mother, “the Creator and Destroyer.”) But the box containing the manuscript comes to stand as a metaphor for another box:

I had come to the end of the book, and the character has at last made it to Bali and he’s lying there under the stars, remembering that first vacation he tried to take in Mexico, and how, when he came home, all he found left of his mother was ashes in an urn, in a box….

A similar transposition occurs in Gray’s Anatomy. Gray discovers that he has developed a rare condition during a storytelling workshop when, in an exercise, he must hold eye contact with one of his students:

As I looked into her eyes, her entire face began to slide off her skull. It was pouring down; it was drooling off like in a horror movie, like a bad LSD trip; and then her face turned into an oval ball of pulsing white light.

After being told by a doctor that he needs eye surgery, Gray, panicked, casts about wildly for an alternative therapy. He visits an American Indian sweat lodge outside of Minneapolis, a nutritional ophthalmologist in Poughkeepsie, and Pini Lopa, a “psychic surgeon” in Manila. Lopa is a kind of faith healer; during his “Halloween funhouse” treatments he reaches into his patients’ bodies and pulls out their diseased organs, tossing them across the room as blood spatters through the air. (After being operated upon, Gray realizes that the blood is fake and the human organs are in fact spaghetti and meatballs.) Ultimately the eye ailment becomes an allegory for a greater artistic crisis:

Why of all things should I be losing my ability to see detail? This is what I totally depend on in order to tell stories. I tell stories about the details of things. If I lost the detail in my right eye, what could I possibly do?

The broader question posed by Gray’s Anatomy is made explicit in journal entries written at the time: “WHO AM I MAKING THIS DRAMA FOR?…My fear is that I will get so good at artifice that I will no longer lead an authentic life…. Afraid this is the beginning of THE TWO YEAR nervous breakdown that mom went through at 50…. Is all of it really only grist for the mill? It feels like it now…. It is a performance. There are no private acts left…. THERE IS NOTHING PRIVATE LEFT.” In a later monologue he would characterize this inability to live “an authentic life” as “committing a subtle form of suicide.”

It is at this point that Gray initiated a new personal crisis: he began having an affair with a publicity director named Kathleen Russo. Two years later she became pregnant with his child. The journals suggest that the impulse for the affair came about, in part, as a way to create a life that was private from his audience: “I feel so lame working on the new monologue [Gray’s Anatomy] because that subject is NOT the immediate issue. The immediate issue is PRIVATE and will remain so.”

The affair with Russo remained private until 1996, when Gray performed a monologue on the subject at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater. It’s a Slippery Slope, along with Morning, Noon and Night, made without Shafransky’s involvement, show Gray moving in a simpler, more restrained direction. They are portraits of his divorce from Shafransky and his life with Russo and their two sons. The twist is that, for the first time in his life, Gray finds himself “on the fearful edge of being happy.” When he gazes into his infant son’s eyes, he experiences a revelation—the “perfect moment” that eludes him so often in his earlier monologues. The writing here is crisp and clever, but the dramatic stakes are lower. Gray’s violent swings between ecstasy and despair are replaced, especially in Morning, by an amiable Xanaxed glow.

Yet even in this period, Gray’s journals remain a litany of brooding. They suggest that the sense of peace he described in his late monologues was transitory—“the well told PARTIAL TRUTH to deflect the private RAW TRUTH.” In 1997 he writes, under the heading “MONTH OF MAY“: “DREAMS, SO MANY DREAMS OF THE WILD SEA, A WILD SEA ALMOST, ALWAYS ALMOST, SWEEPING ME AWAY.” And most grim of all: “It makes me so sad to be happy.”

Then came “THE ACCIDENT.” In 2001, on the second night of a vacation in rural Ireland, a veterinarian’s van crashed into a car containing Gray and four other passengers on a dark country lane. Gray, who wasn’t wearing a seatbelt in the backseat, fractured his hip and his orbital bone, having knocked heads with Russo. Hundreds of bone splinters lodged in his frontal lobe. Steven Soderbergh’s moving documentary about Gray, And Everything Is Going Fine, an assemblage of film footage of Gray’s monologues and television appearances, includes an interview with him in the week before he underwent skull reconstruction surgery. Gray sounded optimistic about the prospect of a new monologue: “I think there’s enormous amounts of material that, once processed, will be something.”

Surgeons at New York Hospital implanted a titanium plate behind Gray’s forehead, but he was never the same.The journals in the following years record a harrowing descent into madness, when he turned one of his greatest talents as a storyteller—his ability to find connections between disparate observations and events—against himself. He began to see the accident as the culmination of a series of premonitions that he’d ignored: the man who owned the house in Ireland died a month before their vacation, but they came anyway. The house was in the town of Mort. On the day of the accident Gray had passed a monastery where men were digging graves; the radio announcer was reading the names of the recently deceased. “I’m feeling that it’s my fault entirely,” he says in Life Interrupted:

What does it mean that the driver of the van that hit us was named Daniel Murphy? And the real estate agent that sold our house in Sag Harbor while we were in Ireland—another calamity—was also named Daniel Murphy? And the head of the Irish Arts Council was named Patrick Murphy? Was I in the grip of some overwhelming form of Murphy’s Law?

The darkly comic tone is a feint; as the diaries show, he took these coincidences to heart. In particular he was haunted by his decision to sell his old house and buy a newer, larger home farther inland. His mother, he constantly reminded himself, had also moved inland before her final nervous breakdown.

Gray kept performing, though between appearances he was institutionalized, medicated, and even subjected, as his mother had been, to electroshock therapy. By the end he couldn’t hold a conversation. He wanted only to talk about his houses—the “piece of shit” new house, and the “sacred ABODE” he had forsaken. “It was the house that did it,” he writes, over and over. “Some people live in houses that are haunted. In this case, the house is haunting me.” Each room, each memory, he turned over in his private hell: “Today, I miss our old guest bedroom so much it affects my heart. Heartache. I can feel it in me that room. Almost taste that room. Oh God.” Most horrible of all, he retained an awareness of what was happening to him. The diaries chart the ascension of his own insanity: “I can’t I CAN NOT LET the children see me go crazy. I can NOT play that one act on them. NO big ‘NO.’ Because I am in the place of my mom now….”

Although his fear of death never ebbed—“I am terrified of dying…. I just can’t face…dying,” he says in the book’s final entry, a recording made in the last weeks of his life—he leapt from the Staten Island Ferry on January 10, 2004. It was the coldest night of the year. Nearly two months later Gray’s corpse washed up on the Greenpoint waterfront.

“I know I won’t be reincarnated,” Gray says near the end of And Everything Is Going Fine. “One of the ways to reincarnate is to tell your story. I get enormous pleasure from that. It’s like coming back.” His legacy persists but his work now exists in a kind of limbo. The monologues, most of which have been published, are the main precursor to what has become an enormously popular genre: confessional nonfiction by writers whose lives have been neither exemplary nor public. But Gray’s monologues were meant to be performed, not read. Could any actor perform them credibly, now or ever in the future?

Soderbergh’s documentary, though necessarily fragmented and condensed, conveys some of Gray’s abilities as a performer, especially his manic energy and his impeccable command of timing, nuance, and inflection. There is humor in the monologues that the written word cannot convey: the way “wedlock” becomes “wed-LOCK,” for instance, or the spontaneous dance of joy he performs in Morning, Noon and Night. But the documentary has the feeling of a greatest-hits reel. The movie adaptations of Gray’s monologues, while more faithful to the monologue form, are oddly inert, in the way that filmed theatrical performances always are. (When his directors resort to sound and visual effects—as Soderbergh does most aggressively in his Gray’s Anatomy—the contrivance can be wearying.)

I saw only one of Gray’s monologues in person, but I’ll never forget it. I was thirteen years old when he performed Gray’s Anatomy at the Vivian Beaumont. In the intimacy of that theater Gray’s delivery was at times violent in its intensity, particularly in the story about the psychic surgeon. I know Gray didn’t use any props but I can still see the spaghetti and meatballs flying through the air.