Saul Steinberg, who died in 1999, was better known for the eighty-nine New Yorker covers that appeared between 1945 and 2004 than for anything else he ever did. The most famous of them was the one that appeared on March 29, 1976, with its comically parochial depiction of what in the mind of a New Yorker the rest of United States looked like beyond the Hudson River all the way to the Pacific Ocean. View of the World from 9th Avenue became a poster sold in every souvenir shop and was freely adapted by chambers of commerce elsewhere to promote their own cities. Time and again, his lawyer had to restrain him from suing someone who ripped off the image and used it on everything from T-shirts to coffee mugs.

As far as Steinberg was concerned, there was nothing in it to make anyone feel superior. When asked what he meant, he said that this is how people everywhere see the world beyond their own neighborhood. He also said that he had to disguise certain things into jokes, so he’d be forgiven by those who might think him rude if he told them the truth directly. He was right about that. One comes away from Steinberg’s cartoons both laughing and feeling uneasy.

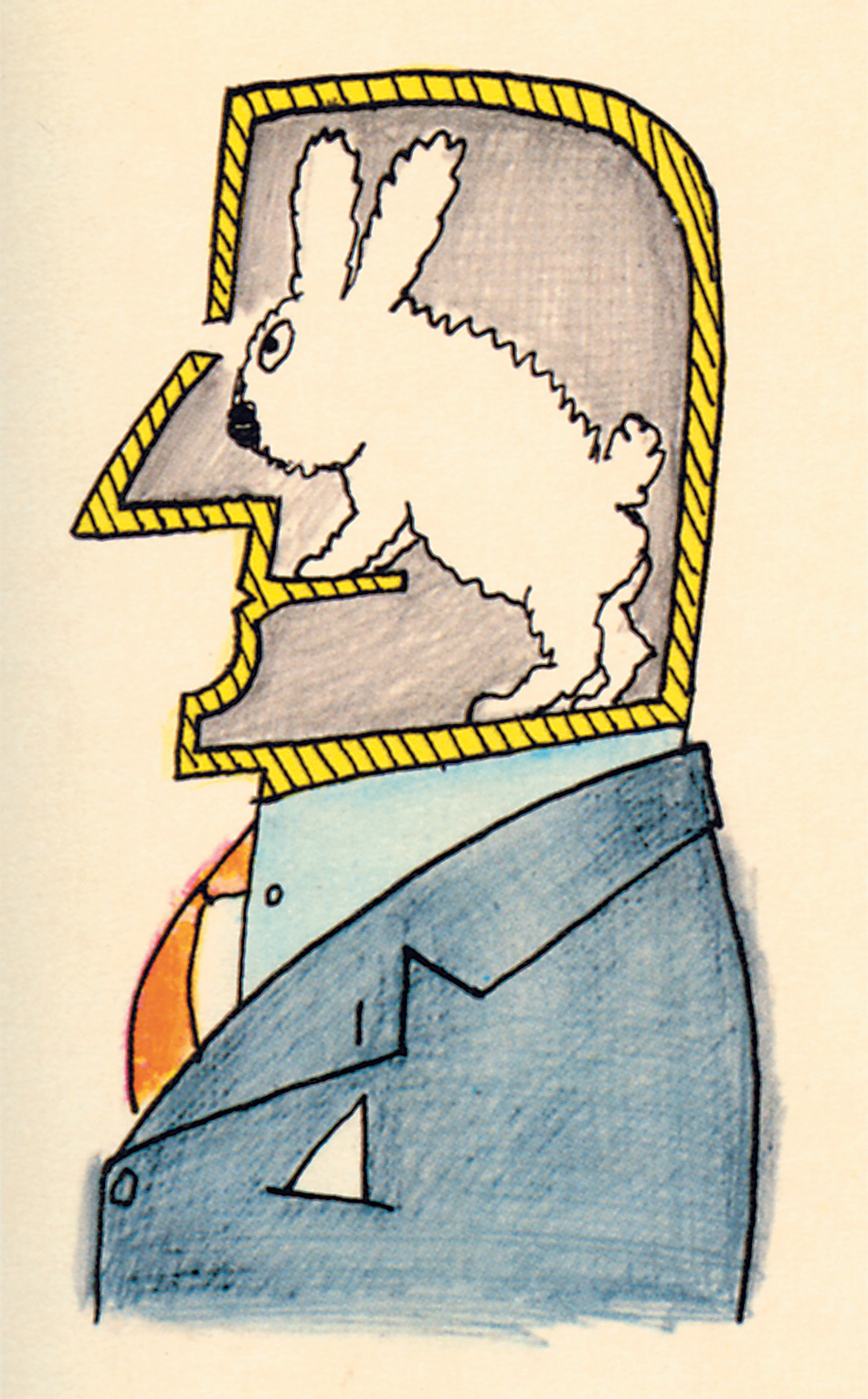

Over more than sixty years, he kept drawing at a time when many painters had convinced themselves that the kind of art they aspired to had little or nothing to do with drawing. He drew both what he observed around him and to make visible what he was thinking, often combining the two. He drew a small dog at the zoo pulling at the leash in order to bark at the lion in the cage, and in a separate drawing, a man dressed in a business suit carrying a huge heroic portrait of himself down the street.

Among hundreds of other memorable images, there is a cat sipping a martini with a goldfish floating in it, the angel of death dressed in a doorman’s uniform outside a funeral home helping a couple of mourners out of a taxi, a group of visitors to an art gallery absorbed in carefully studying blank canvases hanging on its walls, Uncle Sam as a matador waving an American flag in front of a huge Thanksgiving turkey, a mean-looking little kid with a hammer getting ready to strike at a globe, and Uncle Sam playing a violin and the Statue of Liberty beating a toy drum on a street corner while two ants dance wildly at their feet. None of these cartoons and drawings had captions, or had any need of them, since they could be understood by anyone. The adjective “Steinbergian,” which at one time was readily recognizable, was coined as shorthand to describe just such a fresh and irreverent way of seeing.

Many of the artists who were his contemporaries also had their own “look.” By and large, they achieved this by what Harold Rosenberg called “the aesthetics of exclusion,” which ignores the world outside the studio and concentrates on shape, color, texture, and other formal elements of painting. To Steinberg, for whom the problem of depicting reality was central to everything he did, there was no period in the history of art that was not worth investigating. In some of his drawings, figures drawn in Classical, Romantic, Baroque, Mannerist, Expressionist, and cartoonish manner stand talking to each other at a cocktail party. Since each one of these styles not only had its own technique but reflected the ideas and ready-made sentiments of its historical period, drawing for him was a form of philosophical commentary, as well as a kind of sublime doodle, one demonstrating the truth of this proposition about different periods and the other its comic features.

Now that his long association with The New Yorker is a fading memory, and the seven books published during his lifetime that collected his cartoons and drawings and displayed them in their stunning variety and originality have long been out of print, it is good to have this huge, thoroughly absorbing biography of Steinberg by Deirdre Bair to revive interest in him. Except for a very brief memoir, Reflections and Shadows (2002), the result of tape-recorded conversations with his old friend Aldo Buzzi in 1974 and 1977, Steinberg, who infrequently gave interviews (and when he did, often made things up for the sake of a good story), kept much of his life a secret. Only those close to him, I would imagine, fully realized just how complicated and tormented it had been over the years. To all appearances, Steinberg was a famous and successful artist with a busy social life and a vast number of friends and acquaintances, both in New York and in Europe, who, notwithstanding the typical immigrant’s pessimism about the world, seemed to have things under control.

Advertisement

He was born in Râmnicu Sărat, a small town in southeast Romania, in 1914, but moved to Bucharest when he was five years old with his parents and older sister. His father was a printer and a bookbinder by trade, while his mother came from a family of small businessmen who encouraged his father to set up a small factory manufacturing cardboard boxes of all sizes and shapes. Among the uncles on his mother’s side, two were sign painters, one had a shop that sold stationery and schoolbooks, and two were watchmakers who expanded their businesses, one becoming a jeweler, the other selling watches along with musical instruments and phonograph records. Steinberg recalled having no toys as a child, only the wonderlands of his father’s factory and his uncles’ shops. Bucharest, he recalled in a memoir, was an enfant-prodige city, where the avant-garde arts cohabited with primitivism. Dada, he claimed, could not have been invented anywhere else in the world except in Romania, a country of conflicting cultures that had been a part of the Ottoman Empire for several centuries, during which time it became home to Lebanese, Turks, Persians, Egyptians, and Greeks as well as the original population. He, a Jew of Russian origin whose family spoke Yiddish at home, grew up among people who imitated rigid Austro-Hungarian social manners while lining the broad avenues of Bucharest, which bore grand French names, with huge mansions imitating the fanciest Parisian neighborhoods, but their luxury cars had to swerve to avoid hitting an oxcart or a troop of gypsies cooking their dinner.

Once he started school, which took him to the opposite side of Bucharest and required that he commute by streetcar, he had his first experiences of anti-Semitism, which he never forgot. He “divorced” the entire country, he later said, after he discovered that he was not wanted. In his high school, which concentrated on Latin, he was a middling student but a passionate reader of literature. When the time came to enroll at the university, knowing that his parents would not support him if he studied arts and literature, he applied for admission to the school of architecture.

The University of Bucharest turned him down because he was poor in math and lacked academic training in drawing, deeming him more suitable for languages and shunting his application to the liberal arts division. With two friends, who were also denied admission, he began to scheme about going abroad and studying architecture at the Regio Politecnico in Milan. He wanted both to please his parents by his choice of a profession they would approve and to get far away from them. In one of his earliest published cartoons in Italy, he depicted his mother, Rosa, as a huge battle-ax of a woman with a face like Mussolini’s sporting a butcher’s knife in her waistband, accompanied by a cowering little fellow who resembled his father, Moritz, in a landscape littered with what looked like broken statuary or severed body parts.

The “skinny little fellow with the big nose and heavy glasses” was nineteen when he went to study in Milan. Except for one summer vacation and other short visits, he never again lived in Romania. For the first three years, he shared a room with his Romanian friends, and lived in poverty. He didn’t get his degree until 1940, but in the meantime he had the time of his life. Milan was a modern, cosmopolitan city renowned for every form of culture from opera to literature and the arts, and the Polytechnic was an excellent school. Many of his classmates became famous architects, designers, and filmmakers, and a number of them remained lifelong friends. In Milan, Steinberg discovered what were to become the two chief passions of his life: drawing and women.

Instead of joining classmates who copied paintings in museums, he drew street scenes and buildings. In a fairly short time, he became an assured and precise draftsman, filling his sketchbooks with more work than was required. His first cartoons, which brought him fame and money and allowed him to live better, appeared in 1936 in a new semi-weekly satirical newspaper called Bertoldo published by Rizzoli. He would publish more than two hundred of them before June 1938, when race laws imposed by Mussolini forbade Jews, particularly foreign Jews like him, to work in Italy. His friends at Bertoldo and Settebello (the other satirical newspaper he worked for) did not desert him. His unsigned drawings and cartoons continued to appear in both papers, something he later found too complicated to explain—how as a Jewish artist, in danger of being arrested and deported, he practiced his profession as a cartoonist in Fascist Italy while changing residences and fleeing the police.

Advertisement

In 1940, with the expiration of his legal student residence in Italy and with his drawings already appearing in Life magazine and Harper’s Bazaar, he was forced to flee Italy and got as far as Lisbon, only to be stopped by Portuguese authorities because of irregularities in his documents and sent back. In the spring of 1941, he turned himself in to the police and after six weeks of interment in a camp for stateless persons, he was allowed to obtain documents and leave thanks to the help of his friends in Italy who knew some influential people, including his father’s two brothers in the United States, magazine editors Steinberg worked for there, and their contacts in Washington. With the Romanian quota filled for that year, it was arranged for him to wait for the entry visa in Santo Domingo. While there, he sold another drawing to The New Yorker, which wanted more, as well as to the newspaper PM and Mademoiselle. Finally on July 28, 1942, after receiving entry papers, he took a Pan American flight to Miami and from there continued by Greyhound bus to New York. Bair writes:

Despite wartime rationing, restrictions, and blackouts, everything he saw or experienced left him “in a state of utter delight.” The “Cubist elements” that became his lifelong totems assaulted his eye everywhere he looked, and everything he saw became grist for his artistic mill, from the gleaming Chrysler Building, where “Art Deco was merely…Cubism turned decorative,” to the sensuous plastic curves and neon-bright colors of larger-than-life jukeboxes, to women’s dresses (short, to conserve fabric), shoes (usually high, with platforms and stilettos for heels), hairdos (upswept into elaborate rolls and curls), to men’s neckties (large and bright, splashed on colorful zoot suits in rebellion against drab khaki uniforms). Taxis provided fascinating bursts of color in shiny enamel, particularly the sleek flowing lines of the Pontiac sedans, which sported a hood ornament that he thought resembled “a flying Indian that derived directly from Brancusi and his flying birds.”

The noise, the dirt, and the confusion suited him fine. He regretted in later years that he only sketched and did not make large paintings of the kind of America he believed he discovered with its diners, girls, cars, and the feeling of an amusement park that defined even New York skyscrapers. His relatives and friends eased his entry by having a room waiting for him in a hotel on the corner of 11th Street and Sixth Avenue, which he remembered as lined mostly with brownstones, cheap jewelry shops, army and navy stores, used bookstores, pawnshops with guitars and cameras in their windows, and joke stores with rubber fried eggs.

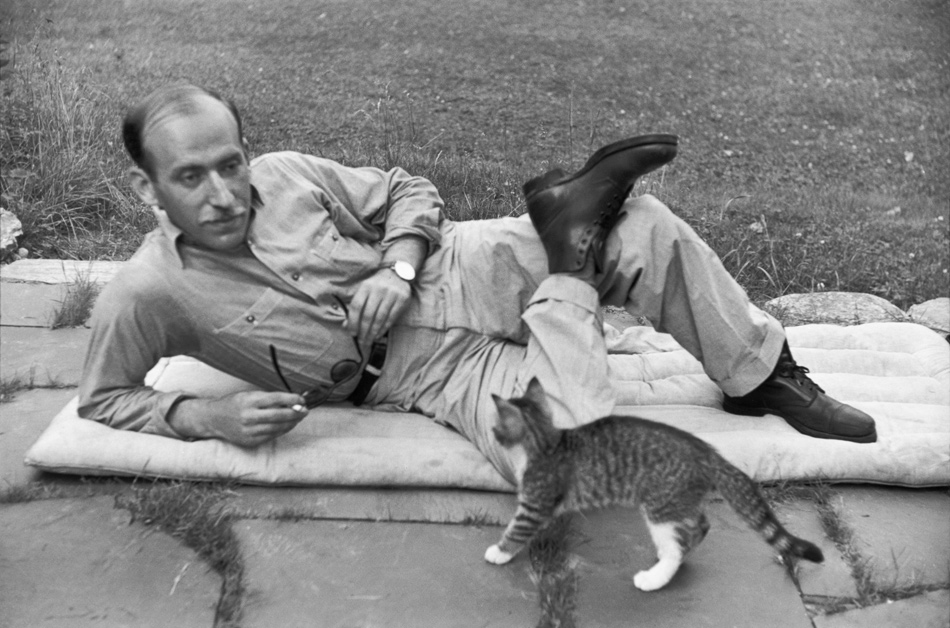

In the summer light, the avenue, he thought, had the look of a Canaletto, with the pink, gold, and brown of the houses bordering the Grand Canal in Venice. Steinberg made many friends among local artists, musicians, actors, and writers, among them Alexander Calder and Philip Guston, the violinist Alexander Schneider, and the critic Harold Rosenberg. One Sunday, the Romanian painter Hedda Sterne, whom he would soon marry, “invited him to lunch and he stayed six weeks.”

What worried him was that he was still a stateless immigrant. The quickest route to becoming a citizen was to join the military, but there was a danger that he might be rejected because of his nearsightedness. Harold Ross, The New Yorker’s editor, got in touch with influential friends in Washington, chief among them William J. Donovan of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), who had already spoken to him about the military’s need for skilled artists and cartoonists who could draw simple pictures to explain military life to soldiers who could not read well. In a single day, February 19, 1943, Steinberg “took the oath to become a US citizen, was commissioned as an ensign in the Naval Reserve, was assigned to the Morale Operations Branch [Propaganda] of the OSS, and received orders to report for duty at the landlocked naval base in Chungking, China.”

His wartime impressions of the daily GI life in China, India, North Africa, and Italy that he sent from his various postings were turned into a series of very popular drawing-essays in The New Yorker. It turns out, as Bair informs us, that many of the images were originally illustrations for naval information and propaganda pamphlets. In the past, Steinberg said, he could only work in solitude. During the war, he learned to sketch in the midst of crowds that thronged to look over his shoulder, ignoring their jostling and touching.

The small paperback book All in Line, in which many of these wartime drawings were collected, was published in 1945, six months after he returned to the United States, and amazingly sold 20,000 copies over the summer, becoming a best seller for the Book-of-the-Month Club. Even more amazing is how quickly Steinberg became a member of the sophisticated magazine and art world in New York. His first one-man exhibition was held in 1943 at the Wakefield Gallery in New York. Three years later, he was in a show at the Museum of Modern Art, “Fourteen Americans,” that included Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Isamu Noguchi, and Mark Tobey. Yet even back then, the question that plagued Steinberg all his life was asked. Returning to his work, the critic reviewing the show for The New York Times wrote: “What’s that stuff got to do with art?” This uncertainty regarding his place in the history of American art has remained unresolved to this day.

What made it even more complicated to classify him is that in addition to being a well-known cartoonist, Steinberg was also a phenomenally successful commercial artist. Unlike De Kooning, who gave up commercial art to concentrate on his painting, Steinberg was suspicious of artists who devoted themselves to “the nobility of art.” Already in 1945, he signed on to do an annual series of Christmas cards for the Museum of Modern Art, an agreement he terminated for a more lucrative commission by Hallmark to do Christmas cards, calendars, and other seasonal items.

He also did drawings for the Neiman Marcus Christmas catalog, dust jackets for books and records, promotional booklets for electric shavers, wallpaper and fabric design, and ads for companies that made everything from copper tubing and sheet metal to Noilly Prat vermouth and Smirnoff vodka. His drawings appeared in Life, Flair, Fortune, Harper’s, and Town & Country. Vogue sent him to Washington to draw the political life of the city and Harper’s Bazaar sent him to cover the fashions in Paris. “If his own work did not actually take a back seat to commercial projects,” Bair writes, “it was certainly coequal with it until the early 1960s.”

It wasn’t just that Steinberg craved riches and success, which he did; he also needed large sums of money in order to support his parents, his sister, and her family, all of whom he had succeeded in having immigrate to France, plus his numerous cousins in Israel and his old girlfriend and oldest friend in Milan. Steinberg emerges from Bair’s biography as a remarkably generous man and a good friend. Much of the comic relief in the book comes from the shocking ungratefulness of his mother, who always found reasons to complain. After he settled her in Nice in a new apartment, she badgered him with requests for a fur coat, a new television, and a trip to a spa with a refined clientele, in addition to countless other demands. Not that his cousins were any better. One of them wanted enough money to buy a taxi or twelve washing machines, so he could open a laundromat, while another one, who was actually quite well-off but didn’t want to touch the money he had deposited in high- interest European accounts, asked Steinberg to send him “a donut maker, a refrigerator, and some radios.” Hard as it is to believe, he honored every one of their requests.

“I lost twenty years,” he said about having to sacrifice creativity so he could make money. He lost more than that, because of other obligations that arose in his hectic life of constant infatuations, lengthy affairs, and one-night stands. Although he was still married to Hedda Sterne and in almost daily contact with her, they lived apart. “Sex was his life,” she said after his death. “Saul thought he had the obligation to seduce every woman he met, no matter whose wife or girl friend she was.” She believed that the most important reason they never divorced was that she was “Saul’s Elaine [de Kooning, the legal wife], who protected Bill from ever having to marry any of his women.” “I already have a wife,” Steinberg replied whenever his longtime girlfriend wanted to get married.

He met Sigrid “Gigi” Spaeth, a stunningly beautiful German girl, at a party at Larry Rivers’s house on July 2, 1960. She was twenty-three years old, born in Baumhelder, Germany, and had first left home to hitchhike to Avignon and Spain “looking for love,” as she said. After living in Paris and working as an au pair, she hitchhiked to Lapland; then after the money ran out went back to her parents to study photography, for which it appears she had a genuine talent. One day on the spur of the moment, she took a plane to New York. She never explained how she supported herself before she met Steinberg, but she had a brief affair with Rivers’s son, an abortion, and was raped by several men in El Paso, Texas, while hitchhiking back from California. She and Steinberg were lovers for the rest of her life, but lived mostly separately. He seldom included her in his busy social life, because she embarrassed him by her manners and her talk. Once, supposedly, she deliberately vomited on a society hostess’s dinner table because the company bored her.

While they fought incessantly, he supported her generously with an apartment, a car, and first-class accommodations on her frequent trips to Europe and Africa. Even when things were fine with Sigrid, Steinberg indulged in ongoing long-term liaisons (some of which lasted from twenty to forty years) with several married women in New York, two in Paris, two in Milan, and another one in Turin. Sigrid knew about them, but assumed that he would eventually divorce Hedda, marry her, and let her have children. In the meantime, when he was away, she spent her time making rounds of the bars where she liked to drink and pick up men.

One is tempted to say that he ruined her life, though she was certainly capable of finding another, more suitable man. Instead, they spent thirty-five years tormenting one another without being able to break away, while enjoying an intense physical relationship. To people who knew her, Sigrid gave the impression of “terrible loneliness.” Because he paid for all her needs, she had nothing she could call her own and felt helpless. There’s no doubt that he felt guilty about what he had done to her and blamed himself, once even writing her a letter from Paris filled with more sentiment than he had expressed in all the years they were together, telling her that he was leaving her his house and studio in Springs, Long Island, after his death. That, alas, is not how things turned out. He could leave nothing to Sigrid because she committed suicide on September 24, 1996, by jumping from the roof of her building on Riverside Drive.

Steinberg’s last years were marked by bouts of severe depression, which grew progressively worse and began even before Sigrid’s suicide. He tried to distract himself by collecting stamps, taking flying and violin lessons, studying German, traveling a great deal, and trying to cure himself with antidepressants and electric shocks. Like any thinking human being, and Steinberg was extremely intelligent, he could not help taking stock of his life as he grew older, feeling remorse about the suffering he had caused people, and worrying about how much he had really accomplished as an artist. His vision of the United States had also darkened considerably following the days of the Vietnam War and street protests. He ended up, one might say, as much a displaced person as he had been in his youth, poring over his collection of Romanian memorabilia, drawing his aunts and uncles from old photographs, seeing them for the first time not only as real people, but as parts of himself.

Deirdre Bair, who has written biographies of Carl Jung, Anaïs Nin, Simone de Beauvoir, and Samuel Beckett, had a formidable task to piece together the story of a secretive man with a busy social life and more double lives than any artist or writer of his time. Her book is frank about his shortcomings, but given the evidence, fair enough—though I would not be surprised if there were objections to her interpretations of particular events by participants who may recall them differently. The problem for her was that Steinberg himself wasn’t quite sure what he had become. As Bair says, he had three identities: a Romanian boy who was ashamed of his country of birth, a stateless Jew in Italy, and an American who loved his adopted country. A solution to the mystery of his identity undoubtedly lies in his cartoons, drawings, and paintings, which reveal his rich inner life and his sense of humor. If one still has trouble placing him as an artist, a look at the writings of Rabelais, Cervantes, Gogol, and Mark Twain may provide a better answer than a visit to an art museum.