During the turbulent Maoist era from the 1950s to 1970s, China clashed militarily with some of its most important neighbors—India, Vietnam, the Soviet Union—and embarked on disastrous interventions in Indonesia and Africa. But by the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping had put China on a development-first policy, advising the country to “hide its capacities and bide its time.” This wasn’t exactly reassuring—implying that at some point China would reveal its true intentions—but from the 1980s through the mid-2000s China had relatively few confrontations, despite its rising economic, political, and military power.

Suddenly, it seems this modesty has evaporated. China’s territorial claims to islands and waters in East Asia are long-standing but they have turned insistent, bellicose, and even provocative, causing a sharp rift between China and many of its neighbors. Most recently, the Philippines and Japan announced that they would become “strategic partners” in settling their maritime disputes with China—anathema to Beijing, which prefers to see these disputes handled separately. Regardless of the merits of China’s claims and actions, from a realpolitik standpoint these disputes and new alliances bespeak major policy blunders in China’s past.

The most serious conflict involves Japan. While China’s actions in Southeast Asia cause many angry statements, most countries there lack the capacity to prevent Chinese ships from patrolling waters they claim as their own. But in Japan, China faces one of the world’s most capable maritime powers. Unlike the Philippines, which hasn’t been able to stop Chinese ships from encroaching on its territorial waters and even dropping markers onto disputed reefs, Japan has actively defended claims to several disputed islands known as the Senkaku in Japanese, Diaoyu in Chinese, and Tiaoyutai by nearby Taiwan (which also claims them, largely based on the same historical arguments used by China).

While other disputes have ended after a few days or weeks, this one has continued now for months. In February, Japan claimed that a Chinese frigate had locked weapons-targeting radar on a Japanese destroyer and helicopter. Almost every few days, Japanese media report on Chinese ships—especially China Marine Surveillance survey ships—sailing without permission inside Japan’s territorial waters around the islands. (At least twenty-eight such violations have been reported since the issue heated up last autumn.) Last year, these tensions helped prepare the way for the election of a nationalistic Japanese prime minister.

It would be easy to blame China’s current leaders for all these problems, but their origins predate the People’s Republic of China and unite many ethnic Chinese from around the world. Although historical records are sketchy, many Chinese are convinced that old maps and mentions of the islands in imperial records imply historical Chinese control. In 1895, China and Japan fought a war and Japan annexed the islands, having declared them uninhabited and belonging to no one. Part of the Ryukyu chain, the islands were administered by the United States after World War II. In 1972, Washington returned the Ryukyus to Tokyo, including the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands.

It was this act that angered many Chinese people, who thought Washington should have returned the islands to a Chinese government. Taiwanese Chinese were especially angry; back then the island saw itself as China’s legal government in exile, and the islands lie quite close by. Also possibly a factor was a 1969 UN survey that suggested vast petroleum reserves under the islands. In the 1970s, Taiwanese civilians made several forays to the islands. Later, Hong Kong residents with no ties to Beijing followed suit.

The most recent wave of activism began in 2006, when private citizens in Hong Kong grew impatient and sent ships to the islands. Over the past year or two, however, the Chinese government seems to have more actively joined in the competition to control the islands, sending government-controlled fishing boats into the islands’ waters. They have now been joined by the survey ships and, outside the territorial waters, the Chinese navy. Many commentators in the Chinese blogosphere note that China’s economy has now surpassed that of Japan and that Japan needs China’s market more than China needs Japan’s products or technology. Whether this sense of superiority has a part in the recent maneuvers is unclear; but the two countries are somewhat suddenly locked in their most sustained and bitter dispute since the war, one that doesn’t have an easy way out for either side.

How all this has come to pass is drawn out in several important new books. They come at the Chinese puzzle from very different perspectives and at times are in sharp disagreement. But at heart they share a common idea: China is burdened with historical baggage that makes its rise less linear than many imagine. By extension the authors imply that the current troubles aren’t inevitable and may be more manageable than some would believe.

Advertisement

Many writers have made the case that China’s rise is imminent and unstoppable. The most famous is probably the columnist Martin Jacques’s When China Rules the World (2009), which has spawned a mini-industry of writing by those who agree or disagree with his op-ed-style take on China’s industrialization and its consequences. The most recent to join the debate is Arvind Subramanian of the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics. In Subramanian’s book Eclipse, China is all but unstoppable—even if its growth slows from the 10 percent it has averaged over the past three decades to, say, a more reasonable 6 percent.

Subramanian argues persuasively that China will eclipse the United States even if Washington pulls off an increasingly improbable 1990s-style turnaround—balancing the budget and getting growth back on track. Thus the common view in Washington is wrong—the game isn’t America’s to lose; barring some sort of catastrophic meltdown, China will win. Within the foreseeable future it will surpass the United States as the world’s biggest economy and, if Washington continues the economic policies that the fiscally conservative author considers suicidal, China will be in a position to dominate it politically as well. The best Washington can do is prepare for relative decline.

This economic point serves a broader foreign-policy argument. To make this, he begins and ends the book with a startling analogy to the 1956 Suez Crisis. Britain had previously won control of the canal at the apogee of its power when it was able to force a debtor state—Egypt—to hand over control. But not too many decades later, in the mid-twentieth century, Britain lost control when it became a debtor country and the rising power, the United States, told it to pull out its troops or face bankruptcy.

Could China do the same? Right now that might seem far-fetched, but Subramanian points out that the United States regularly uses its economic muscle to achieve foreign policy goals. Since World War II, he says, the United States has accounted for 70 percent of economic sanctions imposed around the world; it’s not unimaginable for China to do the same within a few decades. And if the United States remains in huge debt to China, what can Americans do? Could the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute be determined this way? Or China’s claims over Taiwan?

Fortunately, we have some non-economists in the room who make more soothing cases based on the rules of other games. Subramanian argues essentially that economic growth will lead to political dominance. The others concede China’s economic advances but say that supremacy is less likely. They do this from two radically different viewpoints.

The most entertaining and provocative is Edward Luttwak’s The Rise of China vs. the Logic of Strategy, a bold book that flatly predicts that China won’t successfully rise as a superpower, indeed that it cannot in its current incarnation. This isn’t due to growth rates or debt ratios—Luttwak concedes the force of both with a wave of the hand—but because of what he sees as the iron law of strategy, which he says “applies in perfect equality to every culture in every age.”

Luttwak says observers like Subramanian look at China’s economic growth and the rate of military spending and, even allowing for recessions or depressions, project into the future the day that China rules the waves. “Yet that must be the least likely of outcomes, because it would collide with the very logic of strategy in a world of diverse states, each jealous of its autonomy.”

Luttwak argues that China’s growth will cause countries to band together and stymie its rise. Just as nineteenth-century Germany’s economic and military growth caused one-time enemies like France and England to ally with each other (and England to swallow its disgust over tsarist Russia’s primitive repression of human rights and make friends with it), China’s beeline to the top is already causing a reaction, as we see with Japan and the Philippines, not to mention the new welcome being shown to the United States in the region.

Why doesn’t China change course? Here is one of Luttwak’s most interesting ideas, which he calls “great-state autism”—the failure of powers to break free of ways of acting and behaving. Just as Wilhelminian Germany should surely have seen that building a blue-water navy would cause Britain to form alliances against it, so too should China understand that demanding control over islands far from its shores but close to its neighbors’ would cause a backlash. (Here one thinks not so much of the Senkaku/Diaoyus but of the shoals, reefs, and islets in the South China Sea.) Even the battle for the Senkaku/Diaoyus seems to have no satisfactory endgame for China except a permanent state of tension with its most important neighbor.

Advertisement

China’s blindered approach to international affairs leads Luttwak to a humorous discussion of many Chinese people’s conviction that they are heirs to a tactically clever and sophisticated civilization. The Chinese, Luttwak notes, often assume that foreigners are stupid or naive—certainly not up to the wiles of the people who begat The Art of War. In 2011, Luttwak writes, Wang Qishan, a Chinese official who is a head of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue with the United States (and currently a member of the powerful seven-man Standing Committee of the Politburo), said of Americans and Chinese: “It is not easy to really know China because China is an ancient civilization…[whereas] the American people, they’re very simple.”

And yet Luttwak points out that these assumptions haven’t served China well historically or today. Two of China’s last three dynasties were controlled by tiny nomadic groups who outmaneuvered the Chinese, while today the country’s tactics have left it surrounded by suspicious and increasingly hostile countries; indeed, it’s probably no exaggeration to say that China has no real allies. The reason is that Chinese thinking about diplomacy originated in an era when relations were between Chinese states—the Qin, Chu, Lu, Qi, and the others that populated Sun Tzu’s classic work. Almost all were essentially Chinese, facilitating practices like espionage, subversion, and quickly changing sides to cut a quick deal. “Chinese foreign policy evidently presumes that foreign states can be just as practical and opportunistic in their dealings with China.”

And yet this repeatedly fails, as Luttwak demonstrates, because other countries emphasize other practices. In 2007, for example, India was to send 107 young elite civil servants to China as part of a goodwill tour. But China refused to grant a visa to one, saying that because he was from a part of India claimed by China, he didn’t need a visa. Luttwak sees this as part of China’s strategy of manufacturing crises in hopes of obtaining a favorable solution.

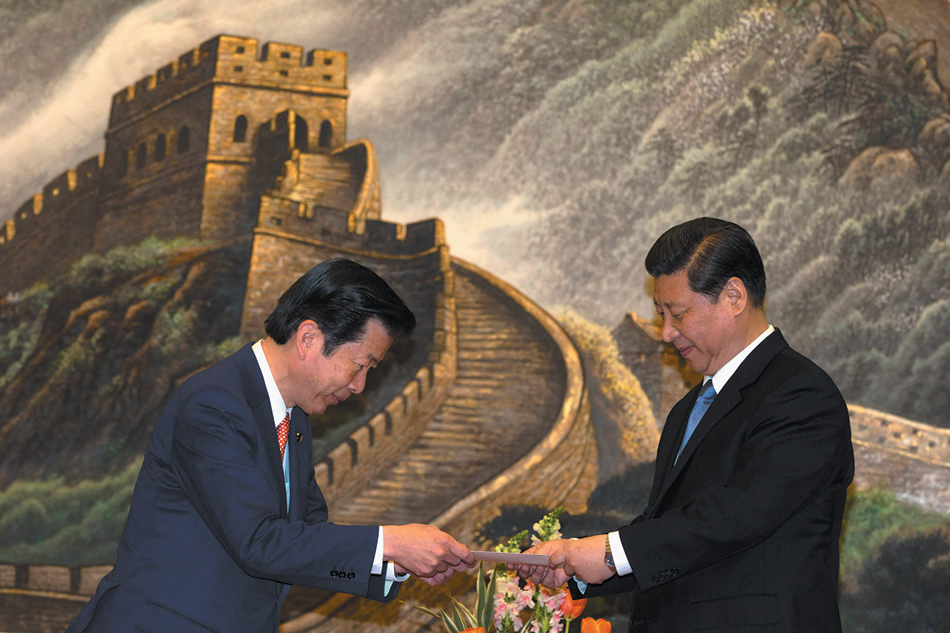

Likewise in 2010, China responded to the arrest of a Chinese fishing captain who had violated Japanese territorial waters by issuing inflammatory statements, arresting Japanese businessmen, and effectively suspending rare earth shipments to Japan. Then it did an about-face and sought to make a deal with Japan. But the Japanese were shocked and frightened by China’s actions and this led directly to the 2012 crisis, with an emboldened nationalist governor of Tokyo threatening to buy the lands claimed by China and assert Japanese sovereignty, which forced the national government to step in to buy the land. This purchase was then the basis for Beijing permitting yet more protests against Japan last autumn that lasted the requisite week before being shut down.

This sounds like bad leadership but Luttwak says that even Bismarck couldn’t fix China’s problem. All rising powers cause a reaction, he says, and rarely gain hegemony unless they create or take advantage of a historic turning point, such as a war. The United States used Japan’s defeat and the decline of Britain and France after World War II to move decisively into the Pacific. Even so, the United States didn’t enter the region making loud demands for territory but as a donor of economic aid. This helped soften America’s rise in the Pacific, even though it was still accompanied by much bitterness—consider how it lost its air and sea bases in the Philippines. By contrast, China is already seen as a predator and has achieved almost nothing.

If accurate, Luttwak’s theory means Americans don’t have to worry too much. China will essentially self-destruct, at least diplomatically. And the list of problems facing China make it seem that this could well be happening right now.

Odd Arne Westad isn’t quite as sure. The Norwegian historian at the London School of Economics believes that China’s history is a burden but it also shows an underestimated ability to adapt and change. A Sinologist who has written widely and lucidly on the cold war, Westad’s Restless Empire is a rich history of the past 250 years of Chinese foreign policy. Like Luttwak, Westad has a revisionist streak in him but this leads him to more optimistic conclusions.

Westad shows how the current crises are in part due to idealism—a belief that the international system has some sort of justice that China can appeal to. In China’s mind, it was humiliated in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and some of its territory, including the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, was stolen. It doesn’t demand that all this land be returned—no one in Beijing wants control of Mongolia, now an independent country that used to be part of the empire—but it has linked some of its maritime claims to this narrative of humiliation and justice. This isn’t the view of a rogue power but one that has a self-interested and one-sided view of justice and history, which is probably how most countries view the world and their past.

Westad is also convinced that the Chinese have been very willing to adapt. One popular view of China is that it didn’t embrace change fast enough, but Westad shows that this really isn’t true. It raced to build railroads, shipyards, and factories in the nineteenth century—as early as in his native Norway, he writes—and the Qing dynasty might have succeeded if it hadn’t been afflicted by a particularly bad run of luck: famines and uprisings, not to mention being invaded and carved up by foreign powers. He also makes a good case for the adaptive abilities of Chiang Kai-shek’s much-maligned Republic of China. Were it not for Japan’s invasion in 1937, the republic probably would have survived.1

“Chinese who embraced the new—when given a chance to do so—always far outnumbered those who did not,” Westad writes, making another important point: the current era of “opening up” isn’t new but the norm. Instead, it was Mao’s thirty years of being cut off that were the anomaly. The reason for this interlude, he says, was World War II. It fatally weakened the republican government—and here he gives a good corrective to the view that the Nationalists didn’t fight, showing how Chiang threw his best troops into battle while the Communists killed more Chinese during the war with their purges and backstabbing than they did Japanese. In addition, foreign powers failed to support China during the war, with the United States giving just 1 percent of its aid to China until 1945. This made people willing to hear Mao’s message that it didn’t need the outside world, leading to the tragedy of his rule. Had history played out otherwise, Mao would have remained a guerrilla and China’s modernization would have continued after the war.

Likewise, Westad gives an important corrective to the facile view that Mao’s destruction opened the way for its capitalistic revival:

China in the 1970s could have gone in many different directions—from genocidal terrorism of the Cambodian kind to democratic development such as on Taiwan. The potential for market developments was there, not because of the destructiveness of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), but despite it, since China had experimented with integrated markets for a long time before the Communists attempted to destroy them.

Like Luttwak, Westad paints a bleak picture of the Communists’ foreign policy. In the 1960s, China had gained some prestige in the developing world for having shunned the United States and, eventually, also spurning the Soviet Union. But it lost this goodwill through Mao’s erratic policies. By blocking aid for Vietnam during its struggle with the United States, Mao ruined the once-close ties between the two and set up China’s humiliatingly inept invasion of Vietnam in 1979. China also had won points for aiding African countries but then frittered this away by supporting Maoist insurgencies, for example in Ghana. One wonders if China’s current forays into Africa aren’t similarly narcissistic; many Africans are amazed at China’s economic successes and investment muscle, but also realize that China operates without even the minimal altruism offered by Western countries.

Relations with the United States likewise haven’t gone how Chinese leaders envisioned. Mao was so out of touch that he believed that Nixon faced an imminent revolution at home and thus had come from a position of weakness to meet the Great Helmsman—after all, in the Chinese Weltbild, what leader comes to the Chinese capital unless to pay tribute? Later, Deng allied China with the United States against the Soviet Union but was essentially just helping the stronger superpower defeat the weaker one, helping set up the past quarter-century of US global hegemony. It’s hard to know what China should have done differently, but Westad is right to poke fun at Westerners’ infatuation with Chinese leaders’ foreign policy savvy.

The Chinese leaders’ gnomic statements on international strategy were taken as ultimate examples of the realist wisdom of an ancient civilization, instead of the ignorance about the world that they really represented.

And yet for all its missteps, China remains the biggest challenge facing not only its neighbors but the United States as well. One of the deans of US–China studies, David Shambaugh, writes of this in the introductory essay to Tangled Titans, an edited volume he put together to try to explain how relations between the two countries had become so bad. “Mutual distrust is pervasive in both governments, and one now finds few bureaucratic actors in either government with a strong mission to cooperate.”2 Shambaugh’s book doesn’t answer exactly how things got this bad but he makes an implicit case that both countries are suffering from Luttwak’s “great-power autism”—set in their ways and unable to change the dynamics.

The dilemma facing American policy makers is well summarized in the forthcoming book by Vali Nasr, a former State Department adviser on Afghanistan and Pakistan. Although his interest is the Muslim world and not so much the territories of East Asia, Nasr describes China and its foreign interventions as at the center of US concerns even in those parts of the world.3 China’s thirst for oil and willingness to pay big for exploration rights is one reason; so is its desire to bring that oil home, either through shipping routes—which necessitate its naval buildup—or pipelines that run through the fragile states of Central Asia.

How optimistic should one be about a changed China being less of a strategic threat? Toward the end of his book, Westad basically assumes that China will rise. As China emerges as “the master player of international capitalism, it is also obvious that the rules of the game are being remade in China,” he writes: a statement that seems to reflect the post-crash period when the West seemed doomed and China’s rise assured. He also writes somewhat implausibly that the Communist Party has “taken over many of the management methods of foreign enterprises”—perhaps, but surely only the worst. Still, his optimism is supported by China’s ability to adapt over the past centuries. Luttwak doesn’t rule out China’s ability to change but puts it another way: only by changing in a way that it has so far resisted, can China rise:

Only a fully democratic China could advance unimpeded to global hegemony, but then the governments of a full democratic China would undoubtedly seek to pursue quite other aims.

-

1

One annoying exception to Westad’s exemplary fairness toward the republican era is his decision to use the mainland pinyin form of rendering Chinese characters for places and groups in Taiwan. Thus the island’s capital is written in the non-standard form “Taibei” instead of “Taipei” and the “Kuomintang” is written “Guomindang” and abbreviated as GMD instead of KMT. Self-determination should apply to spelling too, and outsiders should not choose sides by imposing Communist orthography. ↩

-

2

Tangled Titans: The United States and China, edited by David Shambaugh (Rowman and Littlefield, 2013), p. 5. ↩

-

3

Vali Nasr, The Dispensable Nation: American Foreign Policy in Retreat (to be published by Doubleday this month). ↩