If you were to run into eighteen-year-old Baudy Mazaev on a multicultural Boston street, you’d probably take him for a Portuguese or an Italian; in a pinch you might guess his family origins to lie somewhere farther east. He has straight black hair and an aquiline nose and a build that attests to a long and successful stint as a high school wrestler. Nor does his speech provide any particular clues to his ethnicity: he has the distinctive accent of someone who has grown up on the banks of the Charles River.

Baudy is a native-born American, but like many Americans from immigrant families he also has another identity: he’s a Chechen. His parents, Anna and Makhmud, come from Grozny, the capital of the Chechen Republic, a small province (about the size of Vermont) in Russia’s North Caucasus. That gives the Mazaevs a special place in Boston’s astonishingly rich mosaic of ethnic groups.

Though Boston’s population of Russian-speaking immigrants numbers in the tens of thousands, all but a small number of them are Russian Jews who emigrated from the Soviet Union back in the 1970s and 1980s. By contrast there are only a handful of Chechens in the area; those in the know speak of seven or eight families. Makhmud (who prefers to go by the name “Max”) and Anna moved to the United States in 1994, the same year that war broke out in their homeland: Chechen nationalists had declared independence, and the government in Moscow sent in its forces to repress a rebellion that has never quite stopped since.

Soon after his arrival in the US, Max Mazaev, who had worked as a urologist at a hospital in Grozny, learned that he wouldn’t be able to receive accreditation to practice his specialty in his new homeland (he was in his forties, too old to requalify), and so he shifted to nursing—a line of work that he soon transformed into a solid family business. Today he and Anna run two social centers for elderly Russian-speaking émigrés. I met up with them at one of their venues in the Boston suburb of Newton, a big, well-lit space that, when I arrived, was decorated with multicolored balloons and bore an inscription on one wall that read, in Russian, “Happy Birthday.”

“We’re the first [Chechen] family who lived in Massachusetts,” Anna told me with pride. And for that reason it was only natural that they saw themselves, like so many other immigrants, as part of a support network for members of their own ethnic group who arrived later. In 2002 they welcomed a new family to the community: the Tsarnaevs. “They seemed like a really nice family,” she says. “The kids were really sweet.”

The Tsarnaevs arrived in the US after a brief stay in Dagestan, another Russian republic that abuts Chechnya, but they had spent most of their lives in the Central Asian country of Kyrgyzstan, where Anzor Tsarnaev, the father, had worked for a while in the local prosecutor’s office. But when a new war broke out in Chechnya in 1999, Anzor said, the Kyrgyz authorities (perhaps under pressure from the Kremlin) purged the government’s ranks of anyone with a Chechen background. Anzor lost his job, and for a time, he said, he was even thrown in jail, where his guards subjected him to beatings. It was this abuse that served as the basis for the family’s (ultimately successful) application for refugee status in the US.

Helping the Tsarnaevs adjust to American life proved a challenge. The Mazaevs did what they could, but the family never quite seemed to get it together. Anzor, whose English was limited, earned money by working as an unlicensed car mechanic. He was generally friendly, but his behavior was sometimes erratic—perhaps because he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder that he attributed to his maltreatment back in Kyrgyzstan. He received psychiatric therapy (as another Tsarnaev family friend confirmed to me), and suffered from severe headaches and intense abdominal pain (probably psychosomatic in origin, since doctors were unable to find the cause). In 2009, he got into a fight at a Russian restaurant called Novy Arbat. Someone hit him on the head with a bottle, fracturing his skull.

The mother of the family, Zubeidat, seemed to have problems of her own. “Zubeidat was always jumping from one idea to another,” Max told me, noting that she never quite managed to settle down. The Mazaevs helped to get her a job as a home caregiver, but she soon decided instead to seek a career in the beauty business. She attended a cosmetology school in Woburn, Massachusetts, and earned some income giving facials at the family home, a third-floor apartment they rented on Norfolk Street in Cambridge. For a while she also tried her hand at translating legal documents from Chechen and other Caucasian languages into English, and even attended a few lectures at Harvard. But nothing ever seemed to work out for her. In 2011 she was arrested after shoplifting $1,600 worth of clothing at a Lord and Taylor’s department store. That was the same year that she and her husband filed for divorce.

Advertisement

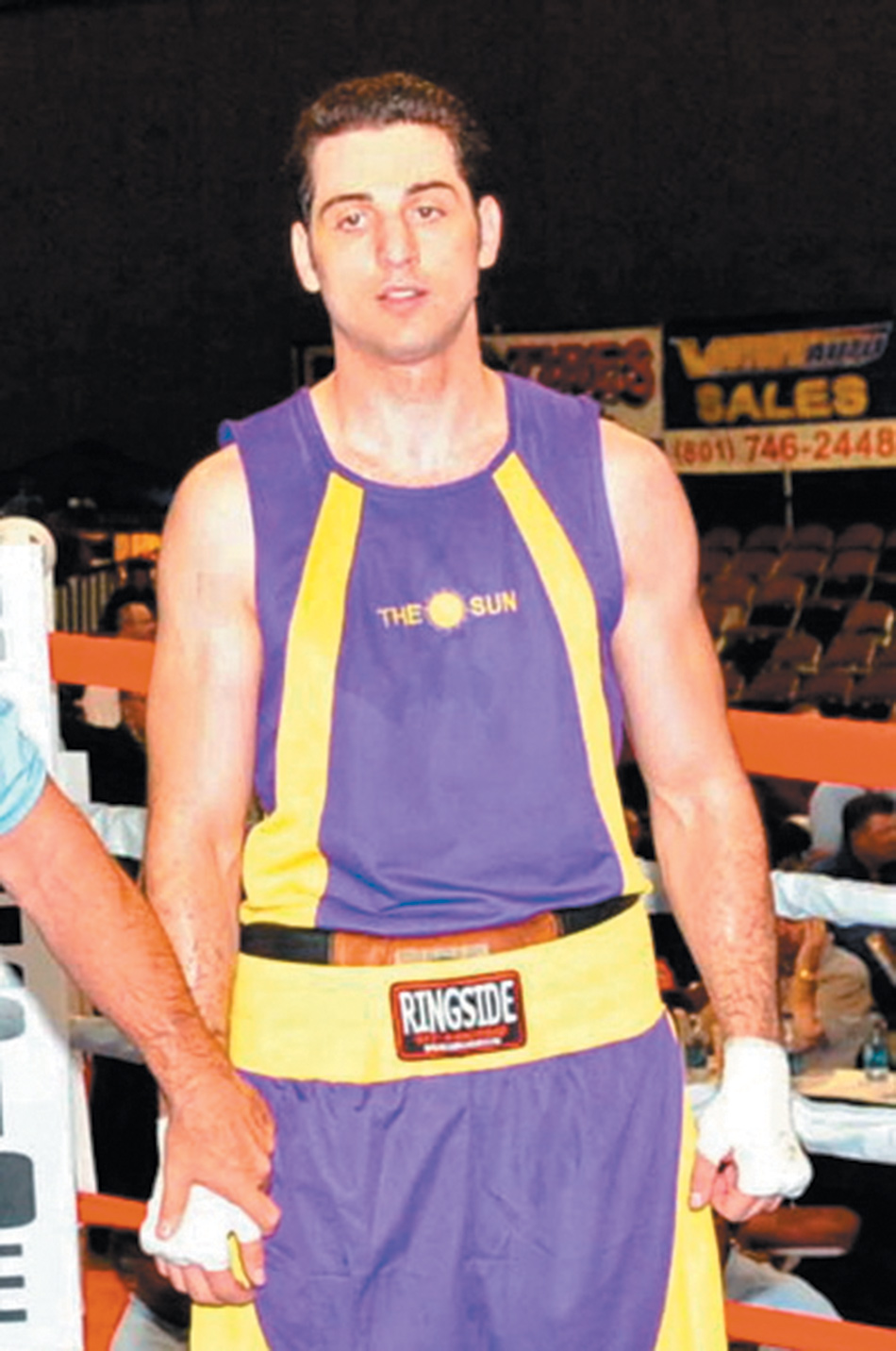

The family’s younger daughter, Ailina, had a tendency to get into fights. The older son, Tamerlan, was a community college dropout who dreamed of starting a musical career; he was also a talented boxer who had a habit of undermining his own prospects with displays of arrogance.

As a child, Baudy Mazaev bonded with the Tsarnaev’s younger son, Dzhokhar, who was a year older. The two spent long hours playing together. In high school, they wrestled on opposing teams (Dzhokhar at Cambridge Rindge and Latin, Baudy at Boston Latin). As the two grew up, they “drifted apart,” says Baudy, though they remained friendly. Dzhokhar, unlike his older brother, was a good student whose affable nature won him many friends. Despite their quirks and their all-too-apparent difficulties, the Tsarnaevs seemed to be okay. “Especially Dzhokhar,” says Anna Mazaev, who begins to weep at the memory. “He was such a sweetheart.”

Anna is not the only person who knew Dzhokhar and who now speaks of him in the past tense. The nineteen-year-old is, in fact, still alive; he is now residing at Federal Medical Center Devens, a hospital prison some forty miles outside of Boston. But for the Mazaevs—as for so many of the other people who had contact with him—it is almost impossible to reconcile their past experience of him with the crimes in which he is now implicated. He and his brother stand accused of orchestrating the horrific April 15 terrorist attack at the Boston Marathon that killed three and injured over 260. One of the dead was Martin Richard, an eight-year-old boy who was standing at the spot where the terrorists placed one of their bombs. The bombs, made from commercially available pressure cookers, were filled with nails and ball bearings intended to cause maximum carnage. Many of the victims lost limbs.

Anna and Max Mazaev were returning from a vacation in Mexico on the day that the FBI released photos of its leading suspects. As they waited in line to clear passport control in the airport, the Mazaevs saw the blurry images, but it never occurred to them to connect the men shown there with the two boys they knew. “My first thinking was I hope they find the bastards and rip them to piece,” Anna recalls. “We love Boston with all our hearts. We’ve been here over twenty years. Everything about Boston very special to us.”

A few hours later, the Tsarnaev brothers reacted to the publication of the photos by going on a criminal rampage that took the life of a young campus security officer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and ended in a spectacular gunfight with police. The confrontation left Tamerlan, twenty-six, dead on a Watertown street. Dzhokhar (known to most of his friends as “Jahar”) managed to escape (inadvertently running over his brother in the process) and disappeared into the night.

By now the identities of the two suspects had become public. The Mazaevs couldn’t believe that the terrorist on the run was that same nice boy who had played with their own son. At 2:25 PM on April 19, Baudy sat down and sent a text message to his friend’s cell phone:

Jahar man if u can read this just turn urself in for the sake of ur parents, ull be so much safer there’s no reason for all of this just do it for everyone’s sake it’ll be better for u it’s time to seek repentance PLEASE JUST TURN YOURSELF IN AND DON’T MAKE IT ANY WORSE

We don’t know whether Dzhokhar ever saw the message. He was found a few hours later, bleeding from multiple wounds, underneath the tarpaulin of a boat parked in a Watertown resident’s backyard. The police took him into custody. It is hard to imagine that he will ever see freedom again.

The biggest question surrounding the marathon bombings, of course, is the one of motive: Why did they do it? I’m not entirely sure that we will ever have a satisfying answer. Given what we know so far, it seems likely that it was Tamerlan, the older brother, who instigated and planned the attacks—but he, of course, is dead. The imprisoned Dzhokhar has told investigators that the brothers undertook the bombings as retaliation against the US for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. That sounds plausible enough on the face of things, in view of what we know about the politics of jihadi terrorists in other parts of the world. At the same time, there are many other details of the Tsarnaev brothers’ case that make it seem starkly unique, more of an outlier than something that can be easily slotted into a larger pattern.

Advertisement

Any analysis must start with Tamerlan. Conversations with those who knew him well yield a portrait of a man who was the lodestar of his family. His mother Zubeidat, in particular, seems to have adored him with an intensity verging on the pathological. During her press conference on April 25 in Dagestan (where she now lives), she startled journalists with expostulations about the beauties of his physique, comparing him at one point to Hercules. Both parents clearly viewed him as their greatest legacy to the world. The father, a former boxer, drove him hard to pursue a career in the sport, often riding along on a bike when his son trained. “He was at the top of the family,” Baudy recalls. “He was the biggest, the strongest, the one everyone loved. Everybody laughed at his jokes.”

Those who associated with Tamerlan recall that he could be charming or considerate when he felt like it—but they also tell of an intensely narcissistic personality whose actual achievements lagged far behind the standards demanded by his intense self-regard. He liked to wear crocodile-leather shoes and silk shirts, but he never found a regular job after he dropped out of Bunker Hill Community College; for a while he delivered pizzas. In 2009, he was briefly arrested for physically assaulting his then girlfriend. That spot on his record probably had a part in the subsequent delay in the decision on his application to obtain US citizenship, which then prevented him from competing in a crucial boxing tournament after the sponsoring organization changed the rules to ban noncitizens from participating. (Other accounts in the media suggest that his efforts to gain citizenship may have been impeded by a 2011 background check conducted on him by the FBI in response to a query from the Russian government, which seems to have suspected him of links to radical Muslims there.) He gave up boxing not long after that—perhaps to his own secret relief. Some of those who spoke with me told me that he was never really keen on the sport, which might explain his apparent reluctance to pursue a strict physical fitness regimen. Those who knew him well told me that he had dreams of becoming a singer or performer, though he doesn’t seem to have acted on them.

Many immigrants, of course, confront similar problems. But Tamerlan’s Chechen background had a way of making itself particularly inconvenient. Traditional Chechen culture places a high value on family ties, and the defense of collective “honor,” which is regarded as vested in the women of the clan, is a high priority. A family friend told me a revealing story from a few years back. Anzor learned that his older daughter, Bella, had been seen in the company of a boy during her junior year of high school. The father deemed this unbecoming behavior, and so he kept the girl at home, out of school, for so long that she was denied credit for the school year.

By tradition, it’s up to the family’s eldest son to enforce the rules for his siblings, so Tamerlan was dispatched to teach his sister’s would-be wooer a lesson: he found the boy and beat him up. The school then suspended Tamerlan for a week (not that he seems to have minded). Baudy recalls that Tamerlan exercised a similarly domineering influence over his younger brother—especially after their father decided to return to Russia about a year ago, leaving them behind. “His brother pressured [Dzhokhar] a lot,” says Baudy. “His brother would have had the most influence—especially when his dad left. That’s the cultural thing.”

As ominous as these details might appear in retrospect, they don’t necessarily indicate a predisposition to terrorism. Nor, indeed, does the fact that Tamerlan experienced a sudden, visible turn toward a conservative version of Islam some four years ago, about the time he decided to get married to his American-born girlfriend, Katherine Russell, whom he persuaded to convert to his religion. The two married and had a baby soon after. Katherine began wearing the headscarf of an observant Muslim woman; so, too, did Tamerlan’s mother, who had hitherto shown a partiality for short skirts and flashy clothes.

The notably irreligious father of the family roundly rejected their new piety, and the divide soon created fresh sources of friction. But the laid-back Dzhokhar, the younger brother, knuckled under. “My brother is telling me to be more Islamic,” Baudy recalls Dzhokhar saying. “Before [Dzhokhar] wouldn’t pray. But then he did. The only reason Jahar started to was because he lived in the same house and they told him to.” That the younger brother was not as committed to religious ideals as his older sibling is borne out by the many accounts of Dzhokhar’s use of drugs: he was an inveterate pot smoker. Yet Dzhokhar’s page on the Russian social media website vKontakte appears to show that he frequented a number of Islamic religious websites (During interrogation by FBI agents after he was taken into custody, Dzhokhar said that he and his brother had watched online sermons by the radical cleric and al-Qaeda sympathizer Anwar al-Awlaki).1 It’s possible, of course, that he felt sincerely wedded to his identity as a Muslim even though he had a hard time avoiding the temptations that face the typical young American.

For a time Tamerlan seems to have gone through a phase in which he adopted the ways of the Salafis, ultraconservative Muslims who want to strip Islam of all of its “modern” accretions and return to the purity of the Prophet Muhammad’s original community of believers. (The Arabic word salaf means “predecessors.”) For a while Tamerlan grew his beard long and wore the simple gown-like garments characteristic of observant Salafis, but he seems to have given this up after a few months; no one knows precisely why. (Did he decide that he needed to look less conspicuous?)

It is worth noting, perhaps, that such practices have little to do with the traditional religious culture in Chechnya itself. A source close to the family tells me that Anzor, the father, even denounced his son’s behavior—especially his decision to marry an American woman rather than a Chechen—as a rejection of their Chechen roots. At the Cambridge mosque where Tamerlan sometimes worshiped, he attracted attention on at least two occasions during prayer services by speaking out against moderate imams who were preaching the virtues of tolerance. “When he first started getting serious about religion, I asked his mother whether he was studying with an imam in the local mosque,” the family friend told me. “She said no, he’s learning by himself on the Internet.”

We now have, perhaps, some idea of what he must have been looking at. The YouTube page registered under Tamerlan’s name has links to rousing sermons by imams (in English) and an instructional video explaining the proper way to perform Muslim rituals (in Russian). But there’s also a clip entitled “The Emergence of Prophesy: Black Flags from Khorasan,” a rousing jihadi anthem favored by al-Qaeda. Another features a ballad that extols the exploits of the Chechen jihadis in their war against the Russians.

For a young Muslim firebrand with roots in the North Caucasus, this must have made for a heady mix of adventure, violence, and seductive (though horribly misguided) idealism—a stark contrast with the grubby reality in which Tamerlan was an unemployed stay-at-home father of a small girl, a man with no visible prospects, dependent on a wife who was working long hours as a home caregiver. This was hardly the grandiose life that his worshipful parents had foreseen for him.

Several members of the extended Tsarnaev family have raised the possibility that a specific person was responsible for Tamerlan’s radicalization. Some accused a mysterious figure named “Misha” of encouraging Tamerlan’s zealousness. “It started in 2009. And it started right there, in Cambridge,” Tamerlan’s uncle, Ruslan Tsarni, said after the attacks. “This person just took his brain. He just brainwashed him completely.” These accusations set off a frenzied search for what some reports have called an Islamic “Svengali,” who was described as an Armenian convert to Islam with a reddish beard. (In late April, FBI sources said that they believed they had located Misha and interviewed him, but journalists were unable to track him down.)

Misha’s name came up during one of my conversations in Boston with people who knew the Tsarnaevs. My interlocutor remembered him well, and told me that his real name was Mikhail Allakhverdov. Finding the right address was not hard, since there’s only one man in the region with that name. I soon found Allakhverdov at the small apartment where he lives with his parents in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in West Warwick, Rhode Island. He confirmed he was a convert to Islam and that he had known Tamerlan Tsarnaev, but he flatly denied any part in the bombings. “I wasn’t his teacher. If I had been his teacher, I would have made sure he never did anything like this,” Allakhverdov said.

A thirty-nine-year-old man of Armenian-Ukrainian descent, Allakhverdov is of medium height and has a thin, reddish-blond beard. When I arrived he was wearing a green and white short-sleeve football jersey and pajama pants. Along with his parents, his American girlfriend was there, and we sat together in a tiny living room that abuts the family kitchen. The girlfriend, who was wearing shorts and a T-shirt, shook my hand, as did Misha himself and his elderly mother and father. This was, in itself, somewhat revealing. A Salafi Muslim man generally doesn’t allow strangers to have physical contact with his wife, mother, or female companion—and it’s even more unlikely that he’d allow an outsider to see a female acquaintance uncovered.

Allakhverdov said he had known Tamerlan in Boston, where he lived until about three years ago, and has not had any contact with him since. He declined to describe the nature of his acquaintance with Tamerlan or the Tsarnaev family, but said he had never met the family members who are now accusing him of radicalizing Tamerlan. He also confirmed he had been interviewed by the FBI and that he has cooperated with the investigation:

I’ve been cooperating entirely with the FBI. I gave them my computer and my phone and everything. I wanted to show I haven’t done anything. And they said they are about to return them to me. And the agents who talked told me they are about to close my case.

An FBI spokesman in Boston declined to comment on an ongoing case. Allakhverdov’s statements, however, seemed to bear out his claim that the FBI has not found any connection between “Misha” and the bomb plot.

It’s certainly possible that Alla- khverdov may have had a part in urging Tamerlan to embrace a more fervent version of Islam. Zubeidat, the mother, has explicitly credited Misha with opening her eyes to Islam: “I wasn’t praying until he prayed in our house, so I just got really ashamed that I am not praying, being a Muslim, being born Muslim,” she said. “I am not praying. Misha, who converted, was praying.”2 Many questions about Misha’s role remain unanswered. The family, who emigrated to the US from post-Soviet Azerbaijan because of the ethnic conflict that broke out there in the early 1990s, was welcoming to me when we met but very nervous, and declined to answer most of my questions about the Tsarnaevs. “We love this country. We never expected anything like this to happen to us,” his father said.

In 2012 Tamerlan suddenly announced to his family that he had decided to return to Dagestan—ostensibly to apply for a renewal of his Russian passport. The family was caught off guard. Zubeidat, the mother, was left to take care of Katherine and their young daughter in his absence. At first he planned to spend three months in Russia, but he later extended his stay, claiming that he had been robbed of all his papers, and that he couldn’t get back to the US without them. At another time he cited a bad back injury from years earlier, and said that he needed to seek treatment.

It’s not clear why he chose to stay. But some reports recently floated in the Russian press, particularly a story in the Moscow weekly Novaya Gazeta, provide grounds for a theory. Anonymous sources have told Russian journalists that Tamerlan had made contact with two young would-be holy warriors who aspired to join the Islamist insurgency in the mountains of Dagestan. One of the men was a Canadian of Russian immigrant background, a convert to Islam, named William Plotnikov. (Like Tamerlan, intriguingly, he was also a boxer.) The other, of mixed Russian-Palestinian parentage, went by the name of Mahmoud Mansur Nidal. The Russian reports claim that Tamerlan met Mansur Nidal several times during his visit to Dagestan, and speculate that Tamerlan, by now eager to prove his worth as a jihadi, was trying to gain admission to one of the insurgent groups so that he could join them in the fight. By necessity, however, such guerrilla movements are extremely picky about accepting unproven new members from the outside world. The vetting process is long and exhaustive, and sometimes includes a “cooling-off period” in which prospective recruits are left to wait for word.

During Tamerlan’s stay, both Plotnikov and Mansur Nidal were killed in confrontations with Russian security forces. Soon after the second man’s death Tamerlan suddenly left Dagestan and rushed off to Moscow, where he caught a plane for the US—apparently without picking up the new Russian passport for which he claimed to have made his journey in the first place. Did he then decide to prove his worth to the cause by carrying out a jihad of his own design on American soil? Or could he have been acting on instructions from people associated with Plotnikov and Mahmoud-Nidal? These are tempting theories. But they should be taken with some skepticism, since they likely come from sources whose interests are impossible to gauge. The Russian government certainly has an interest in gaining US support for Moscow’s own war against its own Islamic radicals.

Each day, indeed, brings fresh questions about the peculiar constellation of forces that seem to have driven the Tsarnaev brothers to commit their crime. We may never get entirely to the bottom of it all.

—May 6, 2013

This Issue

June 6, 2013

The False Claims for Austerity

How to Succeed in Business