On May 20, in a 3–2 decision, the Constitutional Court of Guatemala, the country’s highest tribunal, annulled a portion of the trial of the former dictator General Efraín Ríos Montt and vacated the trial court verdict, issued ten days earlier, holding that Ríos Montt was guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. The decision of the Constitutional Court was based on an alleged violation of due process by the three judges who conducted the trial. That violation involved Ríos Montt’s dismissal of his entire defense team on the first day of the trial on March 19 and the trial court’s brief expulsion of his newly appointed defense counsel, leaving him unrepresented by counsel of his choice for a few hours. This action of the trial court had been addressed in a number of appellate proceedings during the trial and apparently had been held not to damage the prosecution of Ríos Montt. Among other things, the trial court set aside the testimony of witnesses who appeared during the few hours when he had no counsel.

The Constitutional Court had considered this matter previously and had allowed the trial to continue. Its decision on May 20—which is somewhat difficult to comprehend—left in place all the proceedings in the case between the start of the trial on March 19 and April 18, when another appellate court ruled against the claim that due process had been violated. During that period, the prosecution presented its entire case and the defense presented part of its case. The part of the trial that was annulled covered the presentation of a few more defense witnesses, closing arguments, a statement in his own behalf by Ríos Montt, and the verdict and sentence. During this annulled phase of the trial, much of the time was taken up by legal arguments.

As this article goes to press, it is difficult to predict whether the case will move forward, or whether it will be abandoned. What has happened appears to be a setback for the cause of justice in Guatemala, particularly because the Constitutional Court’s decision was handed down against a background of intense lobbying, especially by CACIF, the country’s leading business association, to have the verdict overturned. On the other hand, the action of the Constitutional Court does not do much, if anything, to rehabilitate the reputation of Ríos Montt. It seems likely that he will be remembered principally as the person most responsible for the crimes specified in the verdict that was set aside.

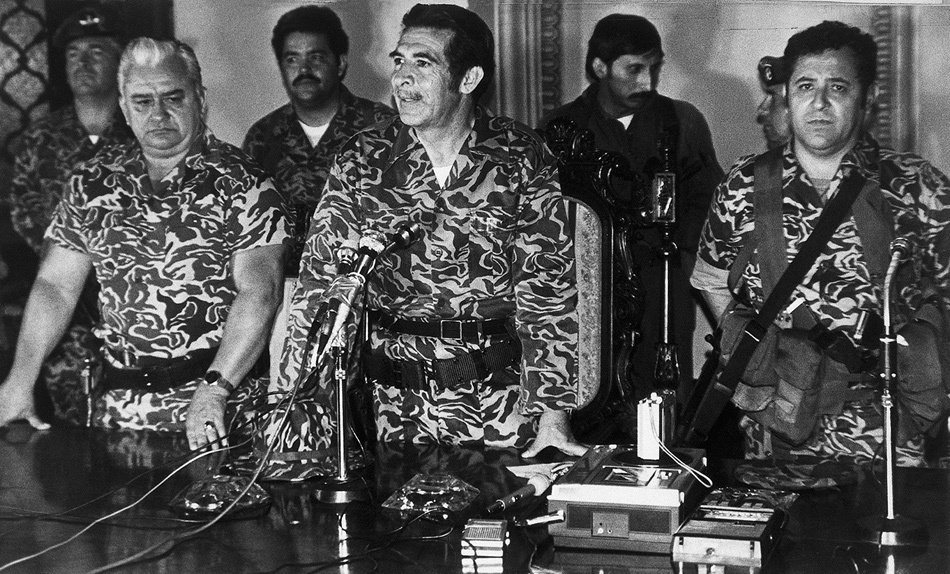

Between 1990 and 2009 there were some sixty-seven prosecutions of heads of state or heads of government for human rights abuses or corruption, or both, a far greater number than ever before.1 Yet the trial of the eighty-six-year-old Ríos Montt, who served as president of Guatemala from the time of his military coup in March 1982 until he was forced out in August 1983, was unique. For the first time, a former head of state was tried for genocide in the courts of his own country.

In effect, the prosecution of Ríos Montt in Guatemala City also condemned the policies of the Reagan administration, which was a resolute apologist for the Guatemalan dictator. Both Reagan himself and high State Department officials denied the killings of thousands of Guatemalans when they were taking place during Ríos Montt’s presidency. They claimed that those who reported on abuses were dupes of the left-wing guerrillas then fighting the Guatemalan government.

Though the mass killings for which he was charged with genocide were at their worst under Ríos Montt, Guatemala’s indigenous people—many loosely called Mayan—who make up most of the country’s population, had long suffered severe repression. In colonial times, going back more than four hundred years, they were subjected to the repartimiento, a system of forced labor. They could not be bought and sold like slaves, but the system produced conditions resembling slavery. Also, the indigenous people of Guatemala were driven off the fertile land in the low-lying areas of the country, and ever since, the great majority have been poor farmers in the country’s picturesque but rocky highlands. The fertile land was owned by people with Spanish and other European backgrounds.

A moment of hope for many in Guatemala came with the election of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán as president in 1951 and his attempts to institute land reform. Yet Árbenz, who was accused in Guatemala and in the United States of Communist sympathies and who legalized the Communist Party, was overthrown in a 1954 coup organized by the Central Intelligence Agency.2 The coup took place a year after the CIA also succeeded, in collaboration with Britain’s MI6, in bringing down another democratically elected leader, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh of Iran. In Iran the coup was provoked by Mossadegh’s attempt to nationalize the British-controlled oil industry. In Guatemala, Árbenz’s proposals for land reform and for raising taxes on foreign corporations doing business there—they had been paying little or nothing—particularly threatened the interests of the United Fruit Company, which controlled large parts of the country. The company wanted him out of power and helped to persuade the Eisenhower administration to take action.

Advertisement

The military regimes that succeeded Árbenz banned labor unions and left-wing political parties, contributing to the emergence of a leftist insurgency. It began in 1960 with a rebellion by nationalist military officers who resented domination by the United States. Some of the insurgents were angry at the CIA’s efforts to train in Guatemala the Cuban exiles who launched the Bay of Pigs invasion a few months later. The revolt drew support from the Communists and, most importantly, from many poor ladinos—Guatemalans of mixed race who do not speak indigenous languages and do not maintain indigenous ways of life.

Significant indigenous support for the insurgency did not emerge until the late 1970s. A major factor then was the formation of the Comité de Unidad Campesina (CUC), not itself a guerrilla organization but one that attempted to unite poor ladinos and indigenous communities in struggles over land issues. Many of its leaders sympathized with the guerrillas. The insurgents gained support in May 1978 when the military forces massacred indigenous people who had gathered for a peaceful protest organized by the CUC. In January 1980, after protesters nonviolently occupied the Spanish embassy, the Guatemalan police, over the protests of the Spanish ambassador, burned the building down, killing thirty-nine people, most of them indigenous peasants.3

The guerrillas also won the support of many students—several of whom died in the embassy fire—and of members of the urban intelligentsia, many of whom became victims of “disappearances”—a practice that spread to other Latin American countries but that seems to have originated in Guatemala in the 1960s. Killings by death squads also became commonplace, particularly between 1978 and 1982 under President Romeo Lucas García, who was eventually ousted by Ríos Montt.

I recall a visit to Guatemala in 1981, six months before Ríos Montt came to power. While checking in at the Camino Real Hotel in Guatemala City, I found a newsletter on the front desk of the sort that some hotels provide for tourists. Instead of reporting about celebrities who had visited the hotel, the first item said that more than a hundred decapitated bodies had been found in a highlands village. During my stay, I learned about many prominent Guatemalans, including leading political figures, who had been assassinated, and also about the rural massacres that had been carried out by armed forces under President Romeo Lucas García and his brother, Benedicto Lucas García, the commander of the armed forces. When Lucas García was overthrown by Ríos Montt in March 1982, my initial reaction was that things could not get any worse. I was mistaken.

One of the crucial moments in the struggle to hold Ríos Montt accountable was the publication in February 1999 of the nine-volume report of the Commission to Clarify Past Human Rights Violations and Acts of Violence That Have Caused the Guatemalan People to Suffer. It is generally known as the Historical Clarification Commission, or CEH for the initials of its name in Spanish (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico). The report documented many of the abuses committed during Ríos Montt’s presidency, and included thousands of cases of murder, rape, and torture.

The CEH was created in 1997 under an agreement concluded in Oslo between the Guatemalan government, the revolutionary group called Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity, and the UN. The agreement ended thirty-six years of armed conflict in Guatemala between the government and guerrilla forces and provided for a national reconciliation process that included the reintegration of guerrillas into Guatemalan society. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan chose a Spanish-speaking German law professor, Christian Tomuschat, as chairman of the CEH. The two other members of the commission were Guatemalans. The CEH had a staff of about two hundred.

When the agreement to create the CEH was reached, many doubted that its report would be very important because in accepting that it would investigate the past, the Guatemalan government had insisted that the report not name those responsible for abuses. The report nevertheless made it clear that the responsibility for by far the greatest number of abuses lay with General Ríos Montt during the seventeen months that he served as president.

The CEH documented 42,275 cases of people who were murdered, disappeared, raped, or tortured, and estimated that the actual number of those murdered or disappeared during the conflict exceeded 200,000. It found that 93 percent of the crimes it documented were committed by the Guatemalan armed forces or by the “civil patrols”—paramilitary forces, created and controlled by the Guatemalan military, in which as many as a million Guatemalan men were required to serve without compensation. Only some 3 percent of the crimes were found to have been committed by the guerrillas, and the CEH could not determine who was responsible for the remaining 4 percent.

Advertisement

The CEH also concluded that 81 percent of the murders and disappearances took place between 1981 and 1983—when Ríos Montt was overthrown by another military coup—and some 48 percent took place in 1982. The report identified regions where hundreds of villages were wiped out and said that the killings in these areas were “acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people”—that is, indigenous inhabitants of Guatemala. According to the CEH, massacres in these areas were carried out “with the knowledge or by order of the highest authorities of the State.”

It seems clear that the ethnic group most severely victimized during Ríos Montt’s tenure was the Ixil, one of Guatemala’s twenty-two distinct indigenous peoples. During the Guatemalan civil war, the Ejercito Guerrillero de los Pobres—EGP, the Guerrilla Army of the Poor—one of the four main guerrilla groups, used the Cuchumatanes Mountains, where the Ixil live, as a base. Government forces believed that the Ixil strongly supported the EGP. The great majority of Ixil villages were destroyed by the Guatemalan army during the Ríos Montt period, according to the CEH, which also documented the killing of about seven thousand of these people. Many of the survivors were forced to flee to remote parts of Guatemala or to Mexico. What happened to the Ixil figured prominently in the CEH’s decision to refer to “acts of genocide”—genocide being defined as acts “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

Previously, there were only a few successful prosecutions of members of the army for crimes committed during the political conflict in Guatemala. The two most notable cases involved the killing of prominent activists who were investigating earlier crimes by the Guatemalan military. One was the murder in 1990 of the anthropologist Myrna Mack, who had been looking into the situation of people who had been forced to leave their villages. In 1993, a sergeant was convicted in a Guatemalan court of stabbing her to death; in 2002, a colonel was convicted of ordering her murder. The determination of Myrna Mack’s sister, Helen Mack, a conservative businesswoman who transformed herself into a dedicated human rights campaigner after the crime, was the main reason that the case against the colonel eventually came to trial.

The other prominent case involved the murder of seventy-five-year-old Bishop Juan Gerardi Conedera in 1998, two days after he published a 1,400-page report for the Human Rights Office of the Catholic Church documenting human rights abuses in the armed conflict. The report covers the same ground as the subsequent CEH report and reached similar conclusions. A colonel, a captain, and a priest who collaborated with them were convicted of bludgeoning the bishop to death.4

Ríos Montt couldn’t be prosecuted in Guatemala in the years following the publication of the CEH report because he had immunity as a member of the Guatemalan Congress. His immunity ended on January 12, 2012, and on January 26, 2012, he became a defendant in a case in which other generals were being prosecuted. Since then, one of those generals, Oscar Mejía Victores, defense minister under Ríos Montt and his successor as president as a result of the August 1983 coup, was found physically and mentally unfit to stand trial by the Guatemalan courts. Along with the case against Ríos Montt, who was held under house arrest while the charges were pending, the prosecution continued against José Rodríguez Sánchez, his chief of military intelligence. They were charged with crimes against humanity as well as genocide.5

At the beginning of the trial of Ríos Montt, in March, the prosecutor alleged that Ríos Montt and Rodríguez Sanchez were responsible for the killing of 1,771 Ixils and the forced displacement of another 29,000. Many of those forced to flee were tortured and many of the women were sexually abused. More than 120 witnesses testified for the prosecution. A large number of them testified in the Ixil language or another indigenous language of the same region, K’iche’, and their testimony had to be translated into Spanish. They told horrifying stories about massacres they had witnessed, often including accounts of family members, including many young children, who were killed by government troops. Some also testified about the ordeals they suffered in the mountains after they fled their villages, where many members of their families had died of starvation.

One day of the trial was largely given over to witnesses who testified about rape. Ten of the twelve women who testified that day covered their heads and faces with rebozos—brightly colored shawls of woven fabric—to protect their identities. Journalists present were instructed by the presiding judge not to publish their names. One woman said that she and her mother were taken to a military base in May 1982, when she was twelve. Soldiers tied her hands and feet and stuffed her mouth with cloth. She watched the rape of her mother and then they raped her. She said, “The blood ran out of me.”6 Her mother died. Other testimony that day was equally harrowing.

Most of the witnesses testified about incidents in the vicinity of Nebaj, the largest of the three towns in what is known as the Ixil Triangle of Guatemala. The prosecution also presented several witnesses from the Forensic Anthropology Foundation, a Guatemalan organization that has exhumed remains at the sites of literally hundreds of massacres to identify those who were killed and to determine how they died. The organization in Guatemala is an offshoot of the similar body in Argentina that was established in 1986. The Argentine group has conducted investigations worldwide and has trained researchers in many countries that suffered from periods of severe repression. Witnesses from the Forensic Anthropology Foundation testified about their extensive exhumations in the Ixil area, and the organization’s director, Fredy Peccerelli, pointed out that the great majority of the dead had been killed by execution rather than in combat.

One of the prosecution witnesses was an American, Beatriz Manz, a professor of anthropology at Berkeley who was my traveling companion on trips to Guatemala. She had interviewed Guatemalan refugees in Mexico in 1982 and, having learned from them what was happening in the Ixil area, went there in 1983 to gather more information. She conducted interviews in the Ixil Triangle when the slaughter in the region was at its worst and provided some of the information that Americas Watch (later, Human Rights Watch) relied on for its reports. At the time, foreign journalists were preoccupied with the wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua and it was too dangerous for domestic human rights organizations to work in Guatemala.

In questioning prosecution witnesses who testified about their own experiences, defense attorneys asked what the witnesses knew about guerrilla activity in the area and whether they had been offered financial incentives to testify. All said they had not been offered any money.

The defense presented only a handful of its own witnesses. Most were military men who testified about the extensive guerrilla presence in the Ixil area and also about Ríos Montt’s lack of control over military practices. One of the witnesses told the court that the president set military policy at a national level, but did not exercise control over the actions of the armed forces. The defense claimed that other witnesses it had planned to present had been impossible to locate.

Though Judge Yassmín Barrios, the presiding judge of the three-member court, attempted to move the trial along briskly, she was frequently stymied by defense tactics that seemed obstructionist. It appeared to some observers that the main defense strategy all along was to trap her into making rulings that would persuade a higher court to invalidate the proceedings. Also, at various points another Guatemalan judge attempted to stop the trial and many prominent public figures in Guatemala, including President Otto Pérez Molina, issued public statements opposing it. According to one such statement that was endorsed by the president on April 16, four weeks after the start of the trial, the proceedings were “betraying the peace and dividing Guatemala.”

That statement, which was signed by high officials of a number of previous governments, also said:

The charge of genocide against officers of the Guatemalan Army constitutes a charge not only against those officers or against the Army, but against the State of Guatemala as a whole….[A conviction would pose] serious dangers for our country, including a worsening of the social and political polarization which will reverse the peace which has been achieved until now.

It did not mention the fact that the Historical Clarification Commission had already made the determination in 1999 that acts of genocide had been committed by the Guatemalan armed forces under the authority of the highest officials of the state.

When President Pérez Molina endorsed the statement opposing the trial, he said that, “as in all wars, there were unjustifiable acts,” but he insisted there had been no genocide. Three weeks later, however, at a point when the trial had been suspended while appellate courts considered the blizzard of defense motions to derail the proceedings, Pérez Molina said it was important that the “trial advance and arrive at a sentence, whether it is in favor or against Ríos Montt.”7

Bringing such cases in Guatemala involves great risks. Witnesses, prosecutors, and judges have all been threatened and, in some cases, forced to flee the country. Others have been killed. In December 2012, an assassin killed a prosecutor who was a member of the team of Guatemala’s attorney general, Claudia Paz y Paz, the driving force behind the case against Ríos Montt. Appointed in 2010, she did much to bring to justice those principally responsible for crimes committed during Guatemala’s long political conflict. She served for a period in the 1990s in the Archbishop’s Office of Human Rights. In addition to prosecuting human rights cases, she has taken on major corruption cases and has also gone after leading drug dealers. The attorney general appears prepared to bring additional prosecutions against those who committed abuses during the long conflict, including former guerrilla leaders.

One of Ríos Montt’s arguments against the prosecution was that a 1986 amnesty law, introduced by his successor Mejía Victores, prohibited the case from going forward. This was rejected by the Guatemalan courts on a number of grounds, among them that Guatemala had ratified the 1948 Genocide Convention, according to which the crime of genocide must be punished. Ríos Montt’s defense witnesses also argued that he was not present when the killings took place and that he was not in command of military officers directly involved in the crimes that were committed when he was president.

Challenging this claim, the prosecution showed the court a filmed interview with Ríos Montt made while he was president in which he said, “If I can’t control the army, then what am I doing here?”8 In addition, the prosecution cited various laws and decrees under which Ríos Montt exercised absolute power and showed that he had been kept informed of operations by radio.

Speaking in his own behalf at the conclusion of the trial—the part that has been annulled—Ríos Montt claimed that as president, he was “occupied with national and international matters” and that the military dealt with military matters. He claimed that regional commanders “were each responsible for their own territory” and that zone commanders operated with autonomy. According to Ríos Montt, “I never authorized, I never proposed, I never ordered acts against any ethnic or religious groups.”

He did not, however, claim that he did not know about the slaughter of the Ixil. If a commander is aware that those under his control have committed or are going to commit such crimes, he is—under international standards of “command responsibility”—required to take all feasible measures to prevent the crimes or to punish those who have committed such crimes. If he does not take such measures, the commander becomes responsible for those crimes.

Knowledge of the crimes is a crucial element. Aside from the information he got from the Guatemalan military, Ríos Montt could hardly have claimed that he was unaware of the reports by Amnesty International and Americas Watch that were issued soon after killings and other crimes were committed. Those reports had a major part in shaping how his country was regarded internationally. Yet he could present no evidence that he ever sought to determine the accuracy of those reports or that he did anything to stop the slaughter of the Ixil, such as issuing an order not to kill them because of their ethnicity.

What emerged from the trial was that while he may not have specifically ordered genocide or crimes against humanity, as president and commander in chief he allowed such crimes to take place. The judges based their conviction of Ríos Montt on command responsibility, and sentenced the eighty-six-year-old to eighty years in prison—fifty years for genocide and another thirty years for crimes against humanity. At the same time, they acquitted his fellow defendant, General Rodríguez Sánchez, on the grounds that, in his case, command responsibility had not been established. Presumably, the charges against him will be dropped if the trial resumes.

Though the CEH had said that American support for the repressive policies of the Guatemalan government was a factor in the human rights abuses that it documented, the efforts by the Reagan administration during the early 1980s to defend Ríos Montt and to discredit his critics did not become an issue at his trial. Yet these deserve to be recalled because it is likely they helped make it possible for such extensive violence to take place.9

The pattern was set soon after Ríos Montt came to power. In 1982, a little more than three months after he took over as president, Amnesty International published a careful report that stated:

Guatemalan security services continue to attempt to control opposition, both violent and non-violent, through widespread killing including the extra-judicial execution of large numbers of rural non-combatants, including entire families, as well as persons suspected of sympathy with violent and nonviolent opposition groups.10

The report listed a large number of rural massacres and attributed fifteen of them to the Guatemalan army, and four to guerrillas. It also said that fifty episodes either could not be attributed to one side or another or involved charges against both sides. This elicited a response to Amnesty from Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Thomas Enders, who said:

We assume that many of the incidents which we are unable to substantiate (e.g.,…March 24–27, April 2, April 5) have been reported to you, as they have to others, by the CUC, which seized the Brazilian Embassy on May 12, the FP-31 or similar groups. Both the CUC and the FP-31 are now closely aligned with, if not largely under the influence of, the guerrilla groups attempting to overthrow the Guatemalan government. Accordingly we have reason to suspect the accuracy of their reports.11

Enders’s letter was followed by briefings on Capitol Hill in which State Department officials insisted that Amnesty’s reporting was based on information supplied by guerrilla sympathizers.

Similarly, when Americas Watch published a report in May 1983 that was based in part on testimony gathered from Guatemalan refugees who had fled into Mexico, Elliott Abrams, then the Reagan administration’s assistant secretary of state for human rights,12 was quoted in the press as saying, “The refugees there are not a representative proportion of the population.” They included, he said, “guerrilla sympathizers.”13

The State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1982, the year in which the CEH found that 48 percent of the killings and disappearances of the thirty-six-year conflict had taken place, asserted that “there has been a decrease in the level of [government] killing.”14 The report was published under the direction of Elliott Abrams. President Reagan himself met with Ríos Montt in Honduras on December 4, 1982, just about at the mid-point of the latter’s tenure as president of Guatemala, and said that the reports of human rights abuses under Ríos Montt were “a bum rap.”15

Though blocked by Congress from furnishing direct military aid to the Guatemalan government, the Reagan administration did what it could to circumvent restrictions, supporting loans to Guatemala by international financial institutions, reclassifying the provision of trucks and jeeps as nonlethal aid, and supplying military spare parts, since a sale of this equipment had been approved at an earlier date. Though such support probably had little effect, that Reagan chose to speak out in support of Ríos Montt and to respond to his critics was a far more serious matter.

Some of the Guatemalan troops carrying out the massacres may have heard that the American president was supporting their leader. As for Ríos Montt, Reagan’s dismissal of the reports of the human rights organizations that monitored the conflict may have encouraged him not to take them seriously.

One of the curious elements of the proceedings against Ríos Montt was that they took place at a moment when Guatemala is governed by another retired general, Otto Pérez Molina. Three decades ago, when the massacres were taking place, Pérez Molina was an officer, with the rank of major, based in Nebaj. There has been little evidence about what he was doing at that time, and only a single witness at the Ríos Montt trial implicated him in abuses. At the very least, however, he must have known what was happening to the Ixil. In the 1990s, Pérez Molina participated in the negotiations that led to the Oslo peace accord.

Up to now, there have been no serious complaints about his actions concerning human rights matters as president, aside from his early statement opposing the trial. What policies he will follow now that the verdict has been annulled remains crucial. He should do everything he can to restart the trial. He must above all ensure the safety of the prosecutors and of Judge Barrios and her fellow judges. Another important test of his commitment to rights will come in 2014 when he will decide whether Claudia Paz y Paz, who was appointed by his predecessor, President Álvaro Colom, will continue as attorney general.

Many of the worst human rights abuses in Latin America took place during the 1970s and the 1980s under the military regimes of that era, and it has taken many years to establish significant accountability for them. In countries such as Argentina and Chile, there have been more than one hundred prosecutions and convictions.16 Prison sentences have been imposed on officers responsible for abuses, as well as on former heads of state of Argentina and Peru. The former dictator of Chile, General Augusto Pinochet, was found unfit to stand trial. The former dictator of Uruguay, Juan Bordaberry, was sentenced to thirty years in prison, before he died in 2011.

The only country in Latin America for which it would be appropriate to use the word “genocide” to describe the crimes committed since World War II, when that term was coined by Raphael Lemkin, author of the Genocide Convention, is Guatemala. It seems clear that the regime wanted to eliminate a considerable part of the indigenous Indian ethnic population. Though some would say there should be no hierarchy among abuses of rights that cause great suffering, a consensus has developed internationally that genocide is the gravest of all crimes. In the struggle for accountability it seemed particularly important that the person who has the highest level of responsibility for the genocide in Guatemala should face a reckoning. Though Ríos Montt may escape judicial condemnation, the hard evidence that led to his conviction will endure.

—May 23, 2013

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Cool, Yet Warm

Facing the Real Gun Problem

-

1

See Ellen L. Lutz and Caitlin Reiger, Prosecuting Heads of State (Cambridge University Press, 2009), in which a list of those prosecuted appears on pp. 295–304. ↩

-

2

See Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer, Bitter Fruit: The Story of the US Coup in Guatemala (Doubleday, 2002). ↩

-

3

See Jean-Marie Simon, Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny (Norton, 1987), p. 102. ↩

-

4

See Francisco Goldman, The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? (Grove, 2007), reviewed in these pages by Aryeh Neier, November 22, 2007. ↩

-

5

One of the differences between the two charges is that genocide requires proof that those who committed the crime acted with the intent to exterminate a group, in whole or in part, on the basis of its race, religion, ethnicity, or nationality. Proving such intent makes it very difficult to establish genocide. In the case of crimes against humanity, it suffices to prove that the perpetrator knew or intended that certain atrocious crimes were carried out on a large scale. ↩

-

6

See the daily blogs on the trial at www.riosmontt-trial.org provided by the Open Society Justice Initiative. ↩

-

7

“Prosecutor Killed in Guatemala Along with 6 Others,” Associated Press, December 24, 2012. ↩

-

8

The interview was conducted by film-maker Pamela Yates and though she did not include the segment in a film on Guatemala she produced at that time, it appears in her 2011 film Granito: How to Nail a Dictator, made with Paco de Onis and Peter Kinoy. ↩

-

9

As in neighboring El Salvador, political violence due to government repression increased sharply in Guatemala after Reagan was elected in November 1980. Attacks on the human rights policies of the outgoing Carter administration by officials of the new administration may have conveyed the view that American pressure on human rights issues would end, and that restrictions on American assistance to these governments because of human rights abuses would be discontinued. ↩

-

10

Amnesty International, “Guatemala: Special Briefing,” July 1982. ↩

-

11

Letter to Patricia Rengel, director of the Washington Office of Amnesty International, September 15, 1982. See Americas Watch, “Human Rights in Guatemala: No Neutrals Allowed” (1982), pp. 119–122. The FP-31 was a small group that probably was aligned with the guerrillas. Its name refers to the fact that the burning of the Spanish embassy took place on January 31. The CUC was not a guerrilla organization, though many of its leaders probably sympathized with the guerrillas. ↩

-

12

More recently, Abrams served as a top official of the National Security Council under President George W. Bush with responsibility for Middle East policy. ↩

-

13

The New York Times, May 8, 1983. ↩

-

14

February 1983, p. 517. Starting with the administration of President Bill Clinton and continuing under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the Country Reports have been depoliticized and are now highly reliable reports on human rights practices worldwide. ↩

-

15

The New York Times, December 5, 1982. ↩

-

16

See Kathryn Sikkink, The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions Are Changing World Politics (Norton, 2011). ↩