“Bird was kind of like the sun, giving off the energy we drew from him,” Max Roach said of the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. The sun set early for Parker, who died at thirty-four of pneumonia on March 12, 1955. He spent his last few days in a suite at the Stanhope Hotel owned by the Baronness Nica de Koenigswarter, a Rothschild heiress who was well known for her patronage of jazz musicians. He’d been watching a juggler on the Tommy Dorsey show when he collapsed. A baseless rumor spread that the baroness’s lover, the drummer Art Blakey, either shot or knocked him out in the middle of a quarrel, but Parker, who had been shooting heroin since he was seventeen, hardly needed help killing himself. He was a world-class musician, but he was also a world-class addict. His body was so haggard that the doctor who examined him estimated his age at fifty-three.

Kansas City Lightning, the first volume of Stanley Crouch’s Parker biography, never gets to the Stanhope. It covers only the first twenty-one years of Parker’s life. But each page is haunted by the demons that brought down the man known as Bird. In the richly evocative set piece that opens the book, Parker turns up late for a gig at the Savoy Ballroom with the Jay McShann Orchestra. Crouch imagines the musicians on stage asking themselves, “Why did this guy have to be the guy with all the talent?… Why did his private life have to mess up everybody’s plans so often?” This is, of course, conjecture, but it’s not unreasonable to think that Parker’s bandmates might have wished that he was more like the courtly and punctual Duke Ellington. Parker often nodded off during concerts, or vanished midway through a set. When he wasn’t playing, he was copping for heroin. He stole from his family and friends. His most lasting relationship was with his horn, which he often pawned when he was in need of a fix. Miles Davis, who worshiped Parker, called him “one of the slimiest and greediest mother fuckers who ever lived.”

But when Parker played, all was forgiven. He has often been accused of abusing his gifts, but few have denied them. As the trumpeter Red Rodney put it, Parker “could play a tomato can and make it sound great.” He was the most imaginative improviser in jazz since Louis Armstrong, and the most influential saxophonist in its history. He was not the only leader of the bebop revolution. The South Carolina–born trumpeter John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, with whom he joined forces at the Three Deuces on 52nd Street in 1944, had an equally strong claim to leadership. Bebop, a highly syncopated, often vertiginously fast style of small-group jazz, was no single musician’s invention. A code as much as a fixed style—“the hipster’s seven types of ambiguity,” Anatole Broyard called it—bop grew out of after-hours jam sessions in Harlem clubs like Minton’s and Monroe’s Uptown House.1 “We need to create something they can’t steal,” the house pianist at Minton’s, Thelonious Monk, said—“they” being either white imitators or (as Gillespie put it) the “no-talent guys.” Yet bop only really came together as a movement when Parker arrived on the scene, playing fast and clean and entirely without vibrato. As the drummer Kenny Clarke recalled, “Bird was running the same way we were, but he was way out ahead of us.” Parker, who disliked the term “bebop,” claimed he was merely “looking for the pretty notes.”

How did Bird take flight? That’s the question that propels Stanley Crouch’s account of his early years in Kansas City. It takes nerve to end a book on Parker before his masterful recordings as a bebop innovator, but Crouch has never lacked for it. Born in 1945 and raised in Los Angeles, where Parker recorded sides for Dial in 1946 and recovered from a breakdown at the Camarillo State Hospital, Crouch grew up with the legend of Charlie Parker. He had a family connection to Parker through his father, James Crouch, who bought heroin from Parker’s wheelchair-bound L.A. dealer, Emmery Byrd, whom Parker immortalized in a tune for Dial as “Moose the Mooch.”

Crouch has been working on this biography since the early 1980s, so long that some assumed it would never see the day. (Some of his early research appeared in Gary Giddins’s elegant monograph of 1987, Celebrating Bird.) In the meantime he has made a name for himself as one of America’s most combative cultural critics, a vituperative opponent of black nationalism and nontraditional forms of jazz. (That he was once a black nationalist and champion of the jazz avant-garde has led him to be seen alternately as a brave truth-teller and a loudmouth renegade.) Like Ross Russell, Parker’s first biographer and his producer at Dial, he took time off from his research on Parker to publish a jazz novel, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome (2000), as if a detour through fiction were a requirement for writing about a figure as mythic and elusive as Bird.

Advertisement

Kansas City Lightning often reads more like a novel than a biography, a companion to books like Michael Ondaatje’s fictionalized portrait of Buddy Bolden, Coming Through Slaughter (1976). A certain reliance on imaginative speculation, if not invention, is inevitable in a book about Charlie Parker. His nonchalant, disengaged attitude, the cool style widely copied by other jazz musicians and their hipster groupies, made him all but inscrutable even to his friends. Notoriously taciturn, he often assumed a fake British accent when he bothered to open his mouth. He liked to put people on, and keep them at bay. Heroin provided him with another fortress against the world. The mask never came off, except when he was in withdrawal. Only a “black novelist,” Nat Hentoff suggested, could “illuminate those parts of the cold inner darkness that finally took over all of Bird.”

Until Crouch, however, black novelists mostly recoiled from the cold inner darkness that so fascinated Norman Mailer and other white writers. Crouch’s mentor Ralph Ellison loathed Parker, though he grudgingly acknowledged the “velocity, brilliance and imagination” of his improvising. In a 1962 essay for the Saturday Review, Ellison depicted Parker as an emotionally stunted, self-pitying trickster who mocked the upright, aspirational morals of the black middle class, and succeeded only in becoming a poster boy for white bohemians. Parker’s greatest work, he claimed, had “a sound of amateurish ineffectuality, as though he could never quite make it.” He was even harsher in private, comparing Parker’s influence to bird shit. When Crouch applied for a fellowship to write his biography, Ellison warned in his recommendation letter of “an unintended pretentiousness; a temptation to place too much of a load of cultural, sociological, and historical analysis upon the slender reed of Parker’s saxophone as upon the brief and narrow social range of his turbulent life.” (Crouch received the fellowship.)

Crouch could not have been unaware of these risks. He had expressed a similar frustration with Parker’s self-destructive side in a bleak 1968 poem, “Up on the Spoon.” Parker, the narrator, describes himself as a “blasphemer” surrounded by “white women following me from club to club,” and confesses to “lynching my music with the second fiddles of the New York Philharmonic/just for fix money.” Since then, however, Crouch has developed a more forgiving view. Though he does not shy from Parker’s darkness, it is his achievement that preoccupies him. He traces that achievement, and Parker’s devil-may-care sensibility, back to the freewheeling milieu of Depression-era Kansas City, where the Democratic boss Tom Pendergast kept the clubs open around the clock, where the finest black swing bands from the southwestern territories ruled the night.

That Parker was a child of Kansas City swing should be obvious, but it has been obscured. The temptation to hear Parker’s music as a complete rupture with swing has been fed not only by his beatnik admirers, who saw him as a kind of natural wonder, but by Parker himself, who insisted that bebop was “no love-child of jazz” but rather “something entirely separate and apart.” Indeed, Parker’s work sounds utterly different from the music that preceded it, particularly in its unusual phrasing, and in its splitting of the four beats in a bar into eight. When Parker launches into his improvisation in “Ko-Ko,” his exhilarating reworking of Ray Noble’s “Cherokee,” he seems to be taking flight and bidding farewell forever to the Swing Era.2 To listen to the recordings Parker made for Savoy and Dial in the mid-1940s is to feel you’re witnessing the birth of modern jazz, with its eighth notes, flatted fifths, and breathless velocity.

No artistic movement, however, is born of immaculate conception. Thanks to the work of Albert Murray, Gary Giddins, and Scott DeVeaux, we now know that the music of Parker and Gillespie evolved from the big-band swing against which it rebelled. Murray, in his 1976 book Stomping the Blues, described Parker as “the most workshop-oriented of all Kansas City apprentices,” rather than a highbrow modernist “dead set on turning dance music into concert music.”

Crouch has praised Stomping the Blues as “the most eloquent book ever written about African-American music,” and there is a lot of Murray in Kansas City Lightning: the celebration of the battle-of-the-bands milieu of Depression-era Kansas City; the insistence that jazz is a proud dance music, rather than an aspiring art music pleading for admission to the concert hall; and above all, the evocation of what Crouch has called “the rich mulatto textures” of American culture. These Murray-esque riffs will be familiar to anyone who has read Crouch’s cultural criticism. But Crouch understands that Bird was more than a gifted exponent of the Kansas City style, and that his inspiration arose from a hidden place that cannot be located on any map. Kansas City Lightning is about what Parker owed to his native city, but also about why he had to make his mark elsewhere.

Advertisement

The glories of Kansas City big-band jazz, which Crouch describes in lush detail, are well known. The formidable leaders of the “territory bands”—Count Basie, Bennie Moten, Walter Page, and others—all plied their trade there. They clashed with one another in fierce, joyful “cutting contests,” and sometimes raided one another’s bands for members. The more than fifty cabarets between 12th and 18th Streets provided an education for young black musicians barred from attending the city’s musical academies. The pianist Mary Lou Williams, who later took part in the bop revolution at Minton’s, remembered Kansas City as a “heavenly” place. It was also a sinner’s paradise, where sex was easily purchased and clubs were supplied with Pendergast’s own brand of whiskey. (When the temperance advocate Carrie Nation came to Kansas City, she was shown the door and told never to return.)

Crouch, who interviewed a number of Kansas City old-timers before they died, writes about its corruption with gleeful fascination and a measure of admiration. The loosening of inhibition that took place after dark, he believes, helped erode the restrictions imposed by race, class, and religious piety. Kansas City was “an improvised world,” a place defined by “the provocative tension between the thrust of individual liberty and the desire for order and safety.”

That tension is the oxygen of jazz, and Parker breathed it in deeply, off as well as on the bandstand. Crouch—a ubiquitous presence on the New York jazz scene since he arrived from Los Angeles in 1975, a man who has lived as close to musicians as a critic can—is just as interested in the jazz life as he is in the music. He is perceptive, and often eloquent, about what Parker learned from Kansas City musicians like the tenor player Lester Young, otherwise known as “Pres,” whom he heard in Count Basie’s Barons of Rhythm—a “handsome and easy-speaking man whose style was individual to the point of sedition.” (Parker clearly studied Pres’s drifting legato lines, though he later denied being influenced by him.) Yet Crouch insists that Parker was shaped as much by Kansas City’s latter-day Wild West ambience as by any specific musical lessons. The blend of high sophistication and rustic blues in Parker’s work was pure Kansas City. Even the astonishing spontaneity of his playing owed something to that rough-and-tumble world, where the law itself had to be improvised.

Parker never felt at home in Kansas City, Missouri. “Melancholy and suspicious,” he spent most of his youth as an outsider looking in. He was born on the other side—the dry, Kansas side—of the city, on August 29, 1920, a “brown baby, with a red undertone to his skin.” (Crouch is a connoisseur of skin tones.) His father, Charles Sr., a “light-skinned and attractive” man of part–Native American ancestry, worked as a cook on a Pullman train but soon disappeared into drink. His mother, Addie, a proud and industrious woman of part-Choctaw ancestry, gave up on her husband and moved her family across the river into a big, two-story house. She cleaned other people’s houses and raised her son as “a homebred aristocrat, a young lord,” sparing him nothing but affection. Addie cut a cool profile, and her relationship to her son seems to have chilled when she took up with a married man, a deacon at a local church. In photographs, the adolescent Parker already “appears removed, almost aloof.” He retreated further into himself after the premature death of his closest friend, Robert Simpson.

There was always something “isolated” about Parker, as Miles Davis observed, but that sense of separateness seems to have imbued him with a sense of special destiny. At fourteen he began a daring secret courtship with Rebecca Ruffin, a light-skinned beauty two years his senior. She was the middle daughter of Fanny Ruffin, who had moved into the Parker home as a boarder with her six children. Rebecca (whom Crouch interviewed) was so mesmerized by Parker that she married him two years later, defying her mother’s warning that he was an “alley rat.” As a teenager, he seemed to lack all outward sign of motivation. He barely went to school, and spent his time “eating, sleeping, pranking, brooding, and living the well-kept life of a reddish-brown prince who had no specific kingdom in sight.”

He preferred gaiter shoes that he could slip into without tying the laces, and tailor-made suits his mother bought him. Making an effort was foreign to him until he took up the alto saxophone, at age fifteen. The myth of Charlie Parker is that he was self-taught. In fact, as Crouch writes, he studied with a man named Alonzo Davis, an heir to a tradition of conservatory-trained black teachers who had “tattooed their knowledge on the brain cells of many young musicians who went on to shape the evolution of vernacular Negro American music.”

Parker seems to have acquired a rapid—and highly exaggerated—sense of confidence on his horn. He was hardly married when he began to stay out all night in clubs, asking to sit in with local musicians when he only knew how to play “Lazy River” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” He was laughed off the stage more than once. His keenest humiliation took place in 1936 at an early morning jam session at the Reno. Sitting in with Count Basie, he belly-flopped: at the end of a thirty-two-bar chorus, he had already raced ahead to the second bar of the next chorus. Jo Jones, the drummer, tossed a cymbal at his feet. His head handed to him on a platter at these cutting sessions, Bird responded by internal exile, and flight. He holed himself up in his room, practicing a dozen hours a day. He learned to play in all twelve keys, unaware that most jazz tunes only required a handful of them. And when the trumpeter Clarence Davis invited him to play at a club in the Ozarks, he leaped at the chance to leave Kansas City.

Working at a comfortable remove from his hometown, Parker began to find his voice on the alto, and to learn how to listen and respond “in digital time” to other musicians: the art that, as Crouch emphasizes, lies at the heart of his genius as an improviser. But he also discovered the pleasures that would kill him. According to Crouch, Parker was first prescribed morphine around 1937, after a car accident in which he broke his ribs. A few months after Rebecca became pregnant with their son Leon, he invited her to watch as he inserted a needle in his arm, then left for the night. That scene, chillingly described by Crouch, left Rebecca in little doubt about where his loyalties stood. Soon afterward she found a letter from another woman under his pillow; he asked her to return it at gunpoint. He gave her crabs and stole from her. When she miscarried their second child, he flushed it down the toilet. The family doctor told her that if he continued to use heroin, he would live no more than eighteen to twenty years: an accurate prediction.

After his stint in the Ozarks, Parker at last found a mentor when he caught the attention of Buster Smith, an alto player in the Blue Devils known as the Professor. Ellison admired his “strange, discontinuous style,” his ability to steer his music to swing dancers from the stage by doubling the tempo. When Parker returned to Kansas City in early 1937, Smith hired him to play with his band at the Antlers, a whites-only club owned by a “Jewish-looking” man who hired only black musicians. According to Crouch, music was not all that Parker learned from the Professor. At the after-hours shows known as “smokers,” the Smith band performed background music for live sex acts:

Men in dresses were seen performing oral sex on other men, or being mounted by men after being lubricated in a slow, sensual preamble. Women had sex with other women. Some puffed cigars with their vaginas; others had sex with animals.

Some might wonder what all this has to do with Charlie Parker, but Crouch argues that these “smokers” exposed him to “the difference between what went on in the conventional world and what happened when people chose to reject the laws of polite society.” The sole source for this stunning anecdote is an interview Crouch conducted in 1981 with the Kansas City trumpeter Orville “Piggy” Minor. Still, it seems clear that Parker never had much use for the “conventional world,” and that he was willing to take extravagant risks for the sake of his art.

To “create a sound that was built for speed,” he began to file down his mouthpiece, ignoring warnings about brass poisoning. He became a master of deflection and mimicry, trying to “sound absolutely unwounded by experience.” Heroin helped: it gave him an aura of self-possession, although in due course it was the needle that owned him. He haunted the clubs on 12th Street and Vine in Kansas City with “mysterious bags under his eyes and an appearance just short of an unmade bed,” only to light up the bandstand. And then, at his first taste of revenge over the Kansas City musicians who had laughed him off the bandstand, he hopped onto a freight train in early 1939, leaving behind his wife and their one-year-old son. He took nothing with him—not even his horn, which he pawned. He lived among hobos and found he liked it, in large part because race didn’t matter to them.3

After a few months in Chicago, where he dazzled Billy Eckstine and pawned a clarinet that belonged to the musician who put him up, he landed in New York in search of his old employer Buster Smith. The visit was cut short by the news that his father had been murdered by a prostitute. But in less than a year, he learned “how things went in the uptown underground.” He began sitting in at Harlem clubs like Monroe’s Uptown House, named for its owner Clark Monroe, a debonair “light-brown-skinned” man who loved music enough to admit a musician with “clothes…as substandard as Charlie Parker’s.” He became known as “Indian” because of the red tinge of his skin, and because he played with “no visual sauce, no extras, just a deadpan stare.” Above all, Parker continued his education as a listener. He paid particularly close attention to the way the pianist Art Tatum reharmonized popular standards during his gig at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack, where Parker is said to have worked as a dishwasher.

It was in New York, not Kansas City, that Parker experienced his great epiphany during a jam session at the Chili House on Seventh Avenue and 139th Street. “I was working over Cherokee, and, as I did, I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes, I could play the thing I’d been hearing. I came alive.” He discovered, in other words, that he could create new melodies on the basis of the chord progressions, or “changes,” of standard tunes.

Around that time, in late 1939 or early 1940—just before he returned to Kansas City for his father’s funeral, and on a quixotic mission to save his marriage to Rebecca—he made his first recording. It is just two tracks, “Body and Soul” and “Honeysuckle Rose,” but, as Crouch argues, it reveals that Parker’s style had already fallen into place, with its bracingly “sharp edge,” its “bubbling rhythmic intensity” and “aggressive velocity.” This was the sound that would revolutionize jazz when he returned to New York and made common cause with Dizzy Gillespie and the boppers at Minton’s. When Parker and Gillespie played together, it was, in Gillespie’s words, “like putting salt in rice.”4

For the next few years, it seemed that the poète maudit of bop could do no wrong, at least when he was playing. But as the family doctor warned Rebecca, he was living on borrowed time, and the habit finally caught up with him in the Baroness de Koenigswarter’s suite. “Bird Lives!” his followers proclaimed, as if a man as brilliant as Parker could not possibly be mortal. But Charlie Parker was a man, and Stanley Crouch’s enchanting biography returns him to the soil that nourished him before he took flight.

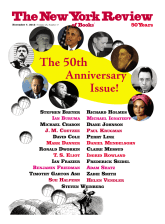

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust

-

1

How that code initially sounded remains a mystery, thanks to the recording ban imposed by the American Federation of Musicians from 1942 to 1944, when bop was born. ↩

-

2

Parker acquired his nickname “Yardbird,” later shortened to Bird, because of his love of chicken, not because of the aerial qualities of his playing, or—as the “smooth jazz” saxophonist Kenny G. claimed—because “his reed would chirp.” ↩

-

3

According to Parker’s widow Chan Richardson, he was happiest hanging out in Lower East Side Ukrainian bars with working-class men who had no idea who he was. Bird, she wrote in her memoir, would have preferred to have been born “white and untalented.” ↩

-

4

Miles Davis, who heard them in Billy Eckstine’s band in St. Louis in 1944, said it was “the greatest feeling I ever had in my life—with my clothes on.” ↩