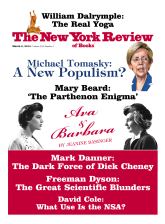

Dominique Nabokov

Diane Johnson, San Francisco, 1987; photograph by Dominique Nabokov. More than fifty of Nabokov’s photographs of writers, editors, and others are collected in Dominique Nabokov: The World of The New York Review of Books, the catalog of a recent exhibition at NYU’s Maison Française. It includes an introduction by Ian Buruma.

Early in Diane Johnson’s new memoir, Flyover Lives, she reports on a house party in Provence, a gathering so fraught with social discomfort and mannerly hostility that it could be a scene in one of her witty, sharply observed novels. En route from Paris to Italy, Johnson and her husband John stop at the rented holiday home of a French friend, Simone, who is married to a former US Army colonel; the couple is sharing the house with a group of retired American generals and their decorative, geisha-like wives. There is considerable fuss about the food (the military wives are accomplished, fiercely competitive cooks) and some amicable small talk. While the men play tennis, the wives alternately interrogate and patronize the newly arrived writer:

“I could never write a book. How marvelous for you,” Lynne was saying. “I’m absolutely too damn stupid and that’s a fact,” which seemed to mean: stupidity is exactly what’s needed for book writing, bitch, and fortunately I’m too smart for that.

After the “Provençale triumph” of dinner, amid a spirited discussion of historical memory, the overburdened Simone—presumably exhausted by the strain of coping with her contentious housemates and perhaps alarmed by the possibility that her husband may be ill—fractures the brittle façade of politesse to hold forth on the Americans’ “indifference to history…. That’s why Americans seem so naive and always invade the wrong countries.’”

Johnson, who lives in Paris, has written about the ways in which being abroad can make one acutely conscious of being American and consequently vulnerable when Europeans criticize our country, even (or especially) when we fear that their complaints are valid. In this case, Johnson’s readers may feel an urge to intercede in her defense. No one could characterize her eleven novels as being indifferent to history. Each takes place at a specific historical moment, and her protagonists display the anxieties of that era, along with the more enduring behaviors we choose to call human nature. Iran in the tense lead-up to the Khomeini revolution provides the background for Persian Nights (1987); Lulu in Marrakech (2008) follows a CIA operative to Morocco during the “war on terror”; the heroine of Lying Low (1978) is on the run from the authorities after having been involved in a laboratory bombing staged to protest the war in Vietnam.

In Johnson’s trilogy of novels set in France—Le Divorce (1997), Le Mariage (2000), and L’Affaire (2003)—the French, perhaps alerted by the success of EuroDisney, seem newly and rather ferociously determined to protect their ancient civilization from the encroachments of Mickey Mouse. Johnson has written a life of Dashiell Hammett, and Lesser Lives (1972)—her biography of Mary Ellen Peacock, the daughter of the novelist Thomas Love Peacock and the wife of George Meredith until she eloped with the painter Henry Wallis—has a great deal of interest to say about Victorian attitudes toward women, marriage, and divorce.

But when Simone declares that “it was unusual for Americans to take an interest in history in any form,” we feel that the force of her conviction would hardly be tempered were someone to remind her that one of her listeners had written a novel about the last days of the Shah. By “history” Simone means genealogy: family origins and roots. “Simone asked John and me about our ancestors, and was triumphant when we gave vague answers…. Neither of us had thought much about them beyond a mention of Scotch-Irishness, whatever that was.”

To write a biography, as Diane Johnson has done twice, and to construct fictional characters as proud of their distinguished heritage as some of the French families in her novels, a writer must consider genealogy, a subject that Lesser Lives addresses directly:

It is usual in biographies to take a family as far back as possible, to discern what is inevitable about the subject because of his forebears: the shape of his nose, say. Biographers of Shelley are fond of pointing out that an ancestor of Shelley’s was sent down from Oxford in 1567 for atheism; some fellow two centuries before can always be discovered by our genealogist aunt to have been just like us—same turn for music, or thievery.

But for Simone, an interest in other people’s origins doesn’t count. What she is saying is that most Americans, presumably excepting the genealogist aunt, “had no idea about anything before their own grandfathers, if that.”

The reader of Flyover Lives has reason to feel thankful when Johnson takes her friend’s criticism to heart and feels chagrined by her own ignorance about where she comes from. Her curiosity awakened, she decides to write about her upbringing and to learn about her ancestry.

Advertisement

What gives her memoir its charm and makes it so consistently beguiling is not so much the events it describes—the hardships braved by previous generations, a tranquil midwestern childhood, a career as a novelist and screenwriter, a troubled first marriage and a happy second one, a sojourn in London, a move to France—as the tone in which Johnson relates her recollections, reflections, and discoveries. Fans of her novels will recognize the cheerful, wry bemusement, the rare combination of optimism and clear-sightedness, the humor and the intelligence we have come to expect from her fictional first-person narrators, and from the knowing voice that moves seamlessly from the consciousness of one character to another.

Like her heroines, Johnson appears to have a boundless curiosity about the world and its inhabitants, a quality that prevents her memoir from falling into the traps of that perilous genre: solipsism and self-involvement. Scattered throughout the book are apt, astute observations. On the subject of our Puritan legacy, Johnson writes, “Religious fervor is back today, we might say it comes and goes like seasonal flu, and each time leaves a nation weakened for the next attack.” In a passage about the wishful belief, apparently widespread among Americans, that they have descended from royalty, she notes that this tradition is “the opposite of, say, the Australians, who came to feel it was chic to have a convict ancestor, the lower and more desperate the better: anyone kicked out of England was someone they wanted.” Describing an ancestor’s fear of having sinned and her determination to improve, she comments, “How modern was her mood of intermittent resolution—like people today with their dieting.”

Johnson chronicles her early years in Moline, Illinois, a verdant city on the east bank of the Mississippi:

What did people do in Moline? My parents were teachers, and my father was principal of the high school. Good teachers and schools, the several country clubs and golf courses, and a professional basketball team reflected the true cultural interests of the community—that and high school football, which was the dominant spectator sport and preoccupation.

In addition, children played Parcheesi, Monopoly, croquet, and touch football; women sewed and made quilts. “Until I began to write these recollections, I may not have fully realized what a sheltered nineteenth-century world Moline still was in the 1940s.”

As is often the case, domestic and civic contentment seems not to have precluded an intense desire to escape. Inspired by reading (an early favorite book was Let’s Go ’Round the World with Bob and Betty) and by the ritual viewing of a certain Mrs. Butterworth’s frescoed ceilings, supposedly painted by Tiepolo (“We children lay on our backs in her sumptuous library, lined up like corpses on a tarmac, and gazed reverently up at the frolicking putti”), Johnson dreamed of seeing the ocean, of accompanying the peripatetic Bob and Betty, and of sailing on a pirate ship. “The books in childhood are the ones that can point your life toward something, and though, in the case of a puny midwestern girl, becoming a pirate was not a realistic goal, it took a long time for me to relinquish that hope.”

In fact what young Diane imagined (though she couldn’t have realized it, at the time) was reverse migration, retracing the footsteps of her ancestor René Cossé or Cosset, who left France for America, where he found his name “quickly transmogrified to Connecticut ears as Ranna Cossitt.” Little is known about Ranna or the reasons for his journey.

“Trying to understand what prompted young Frenchmen to go to North America in 1711 has given me a good deal of sympathy for professional historians, who are expected to know things and not encouraged to speculate.” But as she did in Lesser Lives, Johnson uses conjecture to construct the mostly imagined biography of an obscure historical figure who will then “stand for many others”—and help us comprehend what daily existence was like for many people who lived at that time and in that milieu. Like her earlier book, Flyover Lives demonstrates how much can be learned from—and how much sympathy can be generated by—the few available details of a so-called lesser life: “But we know a lesser life does not seem lesser to the person who leads one…. All the days of his life we do not know about but he was doing something, anyway—something happy or bitter or merely dull. And he is our real brother.”

More reliable information exists about the generations that began with Johnson’s great-great-great-grandmother, Anne Cossitt Perkins, who, along with her daughter Catherine, left a rich cache of letters and diaries. Born in 1779, Anne was a pious girl, obsessed with salvation and damnation. Her journal “concentrates, rather unfortunately, on her own spiritual progress, when we might have preferred to hear about what she ate or wore.” Married at eighteen, Anne and her husband John moved to a primitive cabin on the border between Quebec and Vermont, then called Lower Canada, where they struggled with cold, hunger, loneliness, illness, and the fear of Indian attacks.

Advertisement

More worldly and observant than her mother, Catherine wrote, at the age of seventy-six, a memoir from which her great-great-granddaughter has extracted the literary self-portrait of a woman who again sounds remarkably like a character in a Diane Johnson novel. Recalling her grandfather’s death, Catherine writes, “I asked what Grandpa was going to will me, and Uncle Ambrose Jr. said he was going to will me an old cat. Then I went off crying, as I was not very fond of cats, nor am not to this day.” Reading about Catherine’s notion of happiness (“While one seemed solicitous only for the happiness of another, oneself would be happy and beloved”), one may think of L’Affaire’s heroine, Amy Hawkins, a passionate believer in the gospel preached by the anarchist Prince Kropotkin: the human species can only progress not by competition but through mutual aid.

Despite her views on the subject, Catherine was fated to enjoy only a small portion of happiness. After a protracted engagement during which she supported herself by teaching and fended off a shady, unwanted suitor, she married a doctor, with whom she had nine children, only one of whom outlived her. Her terse account of the death, within a brief span, of three small daughters is heartbreaking: “When I got up, my house was empty, three little prattlers all gone, not one left.”

These tragedies so unhinged her husband Eleazer, already prone to depression, that Catherine threatened to leave him—a highly unusual and daring step for a woman to have considered at that time. “If you cannot restrain your own feelings & keep from making me so unhappy, just give me a few thousand dollars, just enough for me & Charlotte to live upon & you may live where you please and see if you can be any happyer.” But the marriage lasted, and soon the couple’s sorrows were overshadowed by the sufferings of their nation, embroiled in a war in which Eleazer came down firmly on the side of the Abolitionists. “It was above all the Civil War that marked the Midwest. The shade of Abraham Lincoln in his tall hat and the ghosts of Union soldiers and Confederate soldiers still stalk the cornfields of this region and steal along the rivers.”

The memoir’s final section, “Modern Days,” begins with a return to Moline for a series of chapters that form a coherent whole but that also stand alone, as essays. In just three paragraphs, “The Dark Shadow” captures the touching response of children who go to the movies in 1945 and see newsreel images of the “dead people stacked up” and skeletal survivors of the recently liberated Nazi concentration camps:

We knew we couldn’t tell our parents about the terrible thing we had seen. For one thing, they wouldn’t let us go to the movies anymore if they knew. But mainly we wanted to spare them, hoping they would never hear about these murders that had happened far away.

So much less eventful than conflict, less dramatic than misery, happiness is difficult to write about. But the subject recurs throughout the book, and one of its most eloquent chapters concerns the pleasures of the summer house. The vacation retreat that Johnson evokes was a simple log cabin in Upper Michigan, with no indoor plumbing or running water, beloved nonetheless:

Perhaps a summer house is where, forced into your own company, you discover that you are yourself, and maybe that’s something that can’t happen in ordinary life, when you belong to your parents and school. The organized city child is deprived of these hours of messing around alone, though they must be the crucial ones in which we discover things, develop a point of view, learn to rely on ourselves as reliable observers, establish in our own minds that we are we.

At the same time the chapter moves beyond personal history toward the more general considerations one finds in the work of the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, whom Johnson quotes—“‘We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection’”—and questions:

But the summer house is strangely the opposite…. It is not a shelter but a jumping-off place, benignly promising that our explorations and solitary wanderings won’t bring us to grief, and that we’ll be able to survive the more serious wintry perils later on.

One recalls this evocation of a child enjoying solitude and a sense of danger when (in a section that first appeared in this magazine) Johnson describes collaborating with Stanley Kubrick on The Shining, for which she cowrote the screenplay—a film in which a small boy is left alone to explore a deserted hotel and encounter its hideous ghosts. In the essay, “Silver Screen,” Johnson describes working with Mike Nichols and Volker Schlöndorff on projects that were never produced. “I may have been a jinx.” By contrast, her experience with Kubrick was not only pleasurable but productive, and resulted in a masterpiece. Readers who believe, as I do, that The Shining may be the most frightening film ever made will be interested to learn how Johnson and Kubrick endeavored to make the film so disturbing:

Kubrick was concerned that the movie be scary, but what makes something scary? We sought the answer in the works of Freud, especially in his essay on the uncanny, and in other psychological theories for why things frighten us, and about what things are frightening, for instance the sudden animation of an inanimate figure. Dark is scary. Eyes can be scary. Kubrick would avail himself of these and other traditional ingredients of horror…but it was typical of him to want an explanation for the nature of horror, wanting to understand the underlying psychological mechanism.

An earlier chapter follows Johnson from Moline to a women’s college in Missouri, where she received an notably old-fashioned education:

It was mindful, in the world of female education, that we would also be getting married—no alternative was envisaged. So some effort was made to enhance our marketability—each student received a hair and makeup consultation by the resident hairdresser, Mr. Detchmendy.

Encouraged by her teachers to enter a writing contest sponsored by Mademoiselle, Johnson won and was invited to spend a month, during the summer of 1953, working in New York at the magazine’s office, where one of her fellow guest editors was Sylvia Plath. It seems somehow indicative of Johnson’s buoyant and resilient character (and of the differences between her and the anguished Plath) that she experienced a far less traumatic version of an event

subsequently immortalized by Sylvia Plath in her novel The Bell Jar, with vivid images of the twenty girl guest editors throwing up en masse in the women’s bathroom of the Barbizon Hotel, poisoned by crab salad…. I was less sick than some others, because I had never eaten crab and was suspicious of it, an ingredient that had never come to Moline, as far as I knew.

But New York bewildered and intimidated the small-town girl, as did the “gravelly-voiced women editors, who smoked and looked at the world through narrowed eyes, so unlike the moms of Moline, though the moms too smoked like fiends,” and Johnson retreated:

Faced with the challenges of the exotic world, my dreams of adventure shriveled. I was not up to adventure. With two more years of college to go, and with unexpressed misgivings, I went ahead and married my boyfriend as scheduled and moved to California…. I had escaped from Moline for a college in a small town almost like Moline, and again for a scary trip to New York, but I hadn’t really escaped, and now was in another predicament.

That predicament included a marriage that ultimately soured, the couple’s discontent “boiling down to our not liking each other,” and a series of menial jobs that Johnson despised. She completed her education, had children, began to write novels during their naps, endured an acrimonious divorce, and—with her four children and a gloomy au pair in tow—escaped to London to research and write the biography that would become Lesser Lives. In London, she worked on her book, the au pair girl grew steadily more morose, the children thrived, and their mother pined for the married man with whom she was in love and who would become her second (and current) husband John Murray, a doctor specializing in infectious diseases. Just before returning home, Johnson bought a beautiful chrome-yellow Morgan sports car that she couldn’t afford:

I went back to America with my yellow Morgan, and England had changed me completely. V.S. Pritchett says in his autobiography, of his move to France as a young man, “I became a foreigner. For myself, that is what a writer is—a man living on the other side of a frontier.” I had crossed one frontier when I went to California, but never so far as when I went to England. There I got a taste for foreignness, and eventually, like Pritchett, went to live in France.

And so the narrative comes more or less full circle back to that unpleasant encounter with the generals and their spouses, in Provence. On the day after the conversation that would inspire Flyover Lives, Johnson goes to a gorgeous local flower market where she feels a surge of the happiness (“natural placidity plus good luck so far in not having very much to worry about”) that we realize—as she cannot, yet—will be one of her memoir’s principal subjects. “I was so happy being in Europe, the way lots of Americans are. Why is that? We must ask ourselves.”

Returning to the house with her arms full of flowers, she pauses in the kitchen while Simone goes to find a vase, and accidentally overhears the generals and their wives arguing. It soon becomes clear that the reason for their disagreement and for Simone’s anxiety is not, as Johnson had supposed, merely the wives’ unrelenting competitiveness, or the possibility that Simone’s husband might be ill, and definitely not the subject of historical memory. Rather, the source of the palpable tension and the explanation for Simone’s frayed nerves is something much smaller, grubbier, more trivial—that Diane and her husband are not paying guests like the others. This bit of nastiness is nonetheless embarrassing for Simone (who returns to the kitchen in time to hear the complaint about it) and sufficiently distressing to make Johnson and her husband cut short their stay and leave at once.

The memoir concludes with a final passage of reflective speculation: Johnson imagines being a soldier’s mother, entrusting her son to men like the ones she met vacationing in Provence. Then she envisions being a soldier, sweltering “in a hot concrete bunker somewhere, trusting in the greatness of my general, so I hoped—that distant, august figure in charge of my life, not knowing that in life they could seem otherwise.” It’s a perfect—and a perfectly novelistic—ending for a book about historical awareness, with its cautionary reminder: however much we might know or speculate about our forebears and our contemporaries, we may never understand them unless we happen to wander into the next room and overhear them at precisely the right moment, caught unaware in the act of being themselves.