For Richard Nixon’s foreign policy, 1971 was the best of years and the worst of years. He revealed his opening to China, but he connived at genocide in East Pakistan. Fortunately for him, the world marveled at the one, but was largely ignorant of the other.

The two events were connected. General Yahya Khan, the president of Pakistan, was Washington’s principal back channel to Beijing. Nixon had long admired the bluff, no-nonsense manners of the Pakistani military and the dictators it spawned, whereas he disliked the condescension he detected in Indian leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi, the prime minister in 1971. Whereas the Pakistanis had willingly signed on to America’s cold war alliance structures—CENTO in the Middle East and SEATO in Asia—the Indians pursued a “neutralist” foreign policy for which Nixon had no time.

Neutralism seemed to mean friendship with the Soviet Union, whereas Pakistan’s friendship with China was more acceptable because of the split between Beijing and Moscow from the early 1960s.1 When Nixon started early in his presidency to transform the American relationship to China, Yahya emerged as his principal intermediary with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. In October 1970, Nixon asked Yahya to tell the Chinese that the Americans were prepared to send a high-level emissary to Beijing.2 There was no way he would criticize Yahya for genocide when East Pakistan fought to become Bangladesh the following year, and Yahya’s government mounted attacks against East Pakistan in which hundreds of thousands of Bengalis died, while some ten million Bengali refugees fled to India.

The outside world knew nothing about the Pakistani back channel. The State Department was kept out of the loop; only the secretary of state, William Rogers, was informed about the initial visit of Henry Kissinger, the national security adviser, to set up the Nixon trip, and then only on the day before Kissinger landed in Beijing.3 To Nixon’s proclivity for secrecy and his distrust of his nation’s diplomats was added his acute concern about the impact of an opening to China on Republican voters when he came up for reelection in 1972. Everything had to be put neatly in place, justification ready, before a Nixon visit to China could be publicized.

As it turned out, Nixon had the good fortune to learn of Americans’ views of an opening to China before he sent Kissinger to Beijing to arrange the logistics of the trip. The occasion was the people-to-people contacts of April 1971, in the form of table tennis games between Chinese and American players, described in Nicholas Griffin’s revealing and well-researched Ping-Pong Diplomacy: The Secret History Behind the Game That Changed the World.

Griffin, a journalist and a novelist, claims too much in his subtitle. It was Nixon, playing the China card, and Mao, playing the America card—both against the Soviet Union—who changed the world.4 But the invitation by the Chinese to the American team at the 1971 World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya to pay a goodwill visit to China enabled the US president to gauge the likely reactions of Americans when his own visit would be announced.

Griffin in effect rolls two books into one. He starts with a much less well known story, a fascinating account of the life of Ivor Montagu, son of a lord, spy for the Soviet Union, founder of the modern game of table tennis. By the time Ivor’s grandfather Montagu Samuel had set up the bank that made him a millionaire, he had changed his name to Samuel Montagu. On being ennobled, he would have liked to have been known as Lord Montagu, but there already was a Lord Montagu who, according to Griffin, would agree to share his name only if Samuel Montagu shared his wealth. Instead, Montagu took the title of Lord Swaythling, the name of a village between the family’s two Hampshire estates. It became the name of the cup donated by Ivor’s mother for the men’s team that won the table tennis world championship.

Ivor’s father inherited the barony, and Ivor grew up in an extraordinarily privileged background, playing in the garden of No. 10 Downing Street when his father visited the prime minister, meeting the Princess of Wales, later Queen Mary, when she called on his mother, who was a close friend of hers. But as the third son, Ivor would go through life with no more imposing title than the Honorable Ivor Montagu.5

Ivor was born in 1904 and early on began to display leftist sympathies. At his London public school, Westminster, he had to wear an Eton suit and a top hat. But

Advertisement

after school, he’d leave the hat at the lost luggage office in St. James’s Park underground station and pick up his light coat and cloth cap. It was a halfhearted attempt to pass as a member of the working class, betrayed by his favorite accessory, an ebony silver-headed cane.

Griffin believes that Ivor already understood that his class background offered him a thick smokescreen of protection from which he would benefit for decades to come.6

Ivor did not have his brothers’ sporting talents, but by the age of five he had fixated on Ping-Pong as one game that he could master. He persuaded his father to get a table. It sat on the large landing in their Kensington Court mansion and doubled as a bridge table when the foreign and home secretaries dropped around for a rubber.

At the time, Ping-Pong was a passing fad, a little amusement after dinner. It had no official rules. When Ivor went up to Cambridge and found himself unable to compete in team sports that brought popularity, he had two Ping-Pong tables made to order and held a successful tournament. He organized a Cambridge team to challenge Oxford and in a 31–5 victory, Ivor accounted for the five losses. But he was now chair of the national Ping-Pong association, while still only in his teens. He wrote the rules of the sport, widely translated and fated to stand unchanged for decades.

When Ivor discovered that “Ping-Pong” was trademarked by a toy manufacturer, he dissolved the association and immediately reformed it as the Table Tennis Association. When Indian students turned up to what he had billed as the first European championship, he retitled it a world championship. He immediately summoned his foreign interlocutors to what became the first meeting of the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), held in the library at Kensington Court. Ivor, aged twenty-two, was elected president, a post he would hold for over forty years. Griffin quotes Ivor’s later explanation of his focus on the game:

I saw in Table Tennis a sport particularly suited to the lower paid…there could be little profit in it, no income to reward wide advertising, nothing therefore to attract the press…. I plunged into the game as a crusade.7

Ivor was a true believer in Soviet communism from an early age. He started a film society to import Soviet films. In the mid-1930s, he teamed up with Alfred Hitchcock, then still working in England, appropriately as associate producer of a number of his spy films, including The Secret Agent. But Ivor was a spy in plain sight. When he went with the famous Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein to woo Hollywood, the US Department of Labor warned that he was a “clever Moscow propagandist…. Deport him bag and baggage.”

In England, MI5 agents followed him around from the mid-1920s, but perhaps because of his class status and his straight-arrow brothers they didn’t seem to know what to do with him. Once when they obtained a warrant for his arrest, Ivor wrote to the home secretary and it was dropped.8 He joined the British Communist Party and in World War II he spied for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence. After the war, he was followed by MI6 as he traveled freely through the European Communist bloc, both for table tennis and as a member of the World Peace Organization, a Moscow front.9

It was in the latter capacity that he made his first visit to China in 1952. He had been quick off the mark to try to bring this new Communist regime into the ITTF. Within a few months of the creation of the PRC, he had written to Beijing, hoping to get the Chinese to compete in the 1952 world championships in Bombay, but without success. When Ivor realized that the participation of Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (ROC) was not acceptable to the PRC, he simply bowed to Beijing’s wishes; “always thinking like an idealist, always acting like a cynic,” he told Taiwan that it could only participate from then on as “Taiwan Province of the PRC.”10

China first played in 1953, won its first individual men’s world championship in 1959, and accepted Ivor’s invitation to host the games in 1961. But it turned out that 1961 was the third year of the great Chinese famine, triggered by Mao’s Great Leap Forward, in which tens of millions died. Griffin has a good and detailed description of the logistical and psychological means by which the Chinese fed and trained their team during those terrible times. They were so successful that the Chinese carried off the men’s and women’s singles titles and defeated the Japanese to win the men’s team championship, the Swaythling Cup, for the first time. The Chinese players became national heroes. China went Ping-Pong crazy.11

Advertisement

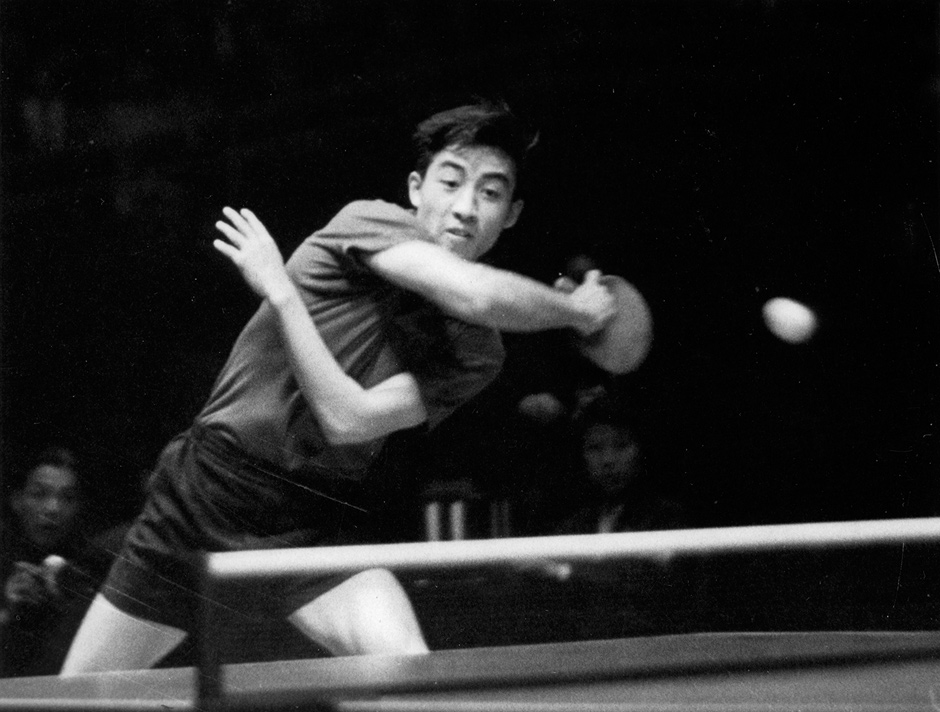

By the time of the Nagoya championships in 1971, Mao was putting his people through another trauma, the Cultural Revolution. This time the Ping-Pong team was not insulated from the catastrophe that had hit the country. Marshal He Long, China’s sports czar and the team’s protector, was purged. When the team returned from abroad in 1966, there was nobody to greet them at the airport and a leading male player was immediately arrested. Their living quarters had been stripped bare. Practicing their game was banned. China failed to attend the next two world championships and Japan recovered its dominant position. The Chinese team split politically, the leading players inevitably being seen as the more conservative. Red Guards invaded and trashed the home of the reigning world champion, Zhuang Zedong.12

The rustication of the Red Guards in 1968 brought no relief to the players. A campaign to “cleanse the class ranks” brought accusations that the whole sports system was “full of spies, traitors and capitalist roaders.” Across China, table tennis tables were destroyed. The national team was accused of “trophyism.” Medal winners at the world championships were particularly criticized. In time, all surviving players were sent down to the countryside to toil as peasants.

The national coach, Fu Qifang, China’s first world champion, Rong Guotuan, and Zhuang Zedong were interrogated and abused at regular struggle sessions. Coach Fu, whose punishments included being beaten by team members and being “humiliated and slapped by younger players,” finally snapped. He hanged himself. Rong Guotuan allegedly also committed suicide, but some suspected that he had been murdered. Zhuang Zedong was beaten and tortured, had his head shaved, and spent four months in prison, but bore his considerable trials with greater fortitude and managed to scramble to safety. He denounced He Long and was later taken up by Mme Mao (Jiang Qing) as her lover, according to rumor.13

Relief came for all the players in 1969. Clashes on the Sino-Soviet border had led Mao to worry that the Soviets would launch a “Pearl Harbor” surprise attack on Beijing. He realized that China could not afford to be at loggerheads with both superpowers simultaneously. Isolation was no longer splendid. It was time for an opening to the less threatening superpower, whose new president, Richard Nixon, had been making placatory gestures, for example by getting the Voice of America to refer to the Chinese capital as Beijing and no longer as “Beiping” as the Republic of China called it; by ending the regular patrols of the 17th Fleet in the Taiwan Straits; and by lifting some restrictions on trade and travel to China.

Zhou Enlai, who had always been a keen supporter of the Chinese table tennis team, brought the leading players out of internal exile in order to send a team to the 1971 Nagoya world championships. He called a meeting of the main players and asked them if they wished to compete. Burned by the Cultural Revolution, a majority voted against the danger of mingling with foreigners. But since Zhou had taken the precaution of gaining Mao’s endorsement of participation, they had no option. They practiced desperately and the Chinese men’s team regained the Swaythling Cup from the Japanese, though Zhuang Zedong withdrew from the men’s singles; the official explanation was that he did not want to play against a Cambodian whose country was under attack by imperialists. (The Chinese women, however, took the singles, doubles, and mixed doubles.)

The last third of Griffin’s book tells how the wily Zhou choreographed Sino-American interaction in Nagoya and subsequently in Beijing, and about the sad fates of the two principal players. The American team, ranked twenty-third in the world, did not come expecting to win. In the US, Ping-Pong was not a great spectator sport; the best players were amateurs who practiced little. The US Table Tennis Association was too poor to subsidize more than three people to go to Nagoya; the rest had to pay their own way. The US team was the only one not in uniform for the opening ceremony. One American player, the hippie teenager Glenn Cowan, wore a headband to control his long hair, and must have looked particularly weird to the Chinese. He became the unwitting instrument of Zhou’s scheming.

Cowan later said that, leaving the stadium after play one day, he was invited aboard the Chinese bus taking their team to their hotel. The Chinese insisted that he mistakenly stumbled onto their bus and the driver shut the door and drove off. Zhuang Zedong’s reaction to this intrusion supports Cowan’s story, because after his horrific experiences during the Cultural Revolution, Zhuang should have shunned this sprig of imperialism. Instead, he later went up to Cowan and presented him with a silk screen and shook his hand. Decades later, Zhuang recalled: “Even now I can’t forget the naive smile on his face.” Griffin comments trenchantly: “Cowan was more like a mark in a con game than an accidental diplomat.” As Kissinger later wrote: “One of the most remarkable gifts of the Chinese is to make the meticulously planned appear spontaneous.” The following day, Cowan presented Zhuang with a T-shirt with a peace symbol in the corner of a painted American flag and the Beatles’ epigram “Let It Be.” His embrace of Zhuang was captured by the photographers the publicity-savvy Cowan had ensured would be there.14

The next stage of Zhou’s plan involved bringing the US team to Beijing. Four other teams had been invited, but Zhou apparently felt that a straightforward invitation to the Americans would be politically too risky. So Zhou’s trusty, the senior Chinese team official in Nagoya, reported back to Beijing as if a courteous greeting from his American opposite numbers was in fact a request for an invitation. Zhou got the foreign ministry to prepare options for Mao to decide yea or nay. The understandably cautious officials recommended nay and Mao agreed, but late that night he changed his mind.

In Nagoya, one of the American team officials was asked by Zhou’s intermediary how he would respond to an invitation to visit China. When he expressed concern about the cost of air fares for the impecunious American team, he was told that all that could be taken care of. The Americans consulted urgently with a China-watcher at the US embassy about the legal implications for the team if it went to China. The diplomat quoted from the latest annual report on foreign relations: “The United States is open to educational, cultural and athletic exchanges with the People’s Republic of China.” Nixon and Kissinger had prepared for a possible opening like this. Ping-Pong diplomacy could proceed.15

Cowan entered China wearing his “Let It Be” T-shirt, purple tie-dye pants, and a floppy yellow hat and carrying a bag of dirty clothes, condoms, and marijuana. His wave good-bye to the Western world as he crossed into China appeared on the front pages of The New York Times and other papers across the globe. No American paper had covered the Nagoya championships, even on the sports pages. Now the Times had five articles on the team’s first day in China and eight the next, all in the international news section. Cowan was in seventh heaven, seeing himself as God’s gift to the media. The three veteran American journalists whom Zhou had cannily invited would toil and he would triumph. When the US and Chinese teams played their friendly match, Cowan’s antics entertained the crowd, though he was not pleased when he realized that his Chinese opponent was deliberately letting him win points.

Cowan’s total self-absorption gradually turned off his teammates, but he was not deterred from self-promotion. When the team was received by Zhou, Cowan nonplussed the premier by asking what he thought of the American hippie movement. But more importantly, before the team left China, Zhou had informed the head of the US Table Tennis Association that the Chinese would like to send a team to America. Back in Washington, Nixon and Kissinger were delighted with the impact of Ping-Pong diplomacy. A Gallup poll revealed that for the first time a majority of Americans favored China’s admission to the United Nations.16 Real diplomacy could proceed.

On their return to the US, the American players were lionized by the press and TV, but initially nobody exploited the opportunities as well as Cowan. He appeared on TV with Johnny Carson and Dinah Shore, began work on a book, announced his intention of setting up Glenn Cowan Table Tennis Centers, and shot a pilot for a syndicated talk show called Reach Out. But nothing panned out. The book, a collection of photographs mainly of himself, did not sell. No network picked up Reach Out. The centers proposal evaporated. By the end of 1971, his brother was describing how in his “crazy states…there were a lot of paranoid delusions that had to do with Russian spies planting stuff in his head.” He was hospitalized and given medication, but according to his mother, “Pot was his thing…. He took the drugs and didn’t take his medication.” His deterioration was probably obvious to the Chinese players when they arrived in America in April 1972.17

Cowan’s partner in fame, Zhuang Zedong, fared better after Nagoya. On his return to China, he was received by Mao. He came to America having been promoted to vice-president of the Chinese Table Tennis Association and made a member of the National People’s Congress. Cowan and Zhuang raised their hands when they saw each other at the airport, but it was Cowan’s last hurrah. At the dinner, he seemed to be on drugs, and was escorted away early and taken back to his mother’s house in California by his agent, a former US Open champion. According to Griffin, Cowan freaked out on each anniversary of the China trip, stopped taking his medications, and could not keep a job. He lost his apartment and declared bankruptcy.

His family gave up on him. Eventually he was living in his car, and when that broke down, on the street. He died during bypass surgery in April 2004, on the thirty-third anniversary of the Nagoya championships. He was fifty-one. There were no press obituaries. Griffin comments: “Cowan’s trajectory had been very American. He had been shot into the stratosphere, tested against the market without a safety net, and then cracked in two by a hard fall.”18

Zhuang Zedong fell too. His trajectory was very Chinese. In 1974, he was made minister of sport and a member of the Party’s Central Committee. He was the guest of honor at a dinner given by the head of the US liaison office in Beijing, George H.W. Bush. Years later he told the London Times: “It was a huge honor to be a member of the Central Committee. But it carried huge risks…. If one was going to survive, one had to form an alliance that would please the Chairman and offer oneself protection.” It was then that he became Jiang Qing’s favorite, and he followed her in excoriating both Deng Xiaoping and even Zhou Enlai. The Sports Commission became a terrifying place where people were denounced, had their scalps shaved, and were “beaten around the head.”19

But when Mao died in 1976, Jiang Qing and her allies were arrested. Zhuang was among the first to fall after the Gang of Four. He was denounced at a meeting of ten thousand athletes and sports officials for turning the National Sports Commission into a fascist dictatorship. After four years of solitary confinement, he was exiled to Shanxi province, where he swept streets. In 1984, he was allowed to return to Beijing to teach in a local sports school, but was shunned by onetime teammates who had suffered under him. He was made to attend anniversary dinners of the Nagoya championships, but never at the main table. On the thirty-fifth anniversary in 2006, he traveled in the Americans’ bus to show them the sights of Beijing. At a karaoke session at the end of the final banquet, he sang “Let It Be.” Cowan’s ninety-year-old mother, there in place of her son, cried.

In 2007, Zhuang was diagnosed with cancer and when hospitalized he was visited by one of Mao’s daughters and Zhou Enlai’s nieces. He was still a hero to some. When he died in February last year, unlike Cowan he was remembered in obituaries around the world. They all mentioned his “spontaneous” meeting with Cowan.20 It is to Griffin’s credit that in this book he has finally nailed that misconception of the encounter in Nagoya, the crucial event that initiated Ping-Pong diplomacy.

-

1

See Gary J. Bass, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide (Knopf, 2013), pp. ii–xv, 3–8. ↩

-

2

Actually this suggestion was first mooted and welcomed in the SinoAmerican ambassadorial talks in Warsaw in early 1970, but a pall fell over these feelers after US troops invaded Cambodia in May 1970, an action that Mao had publicly to denounce. ↩

-

3

William Bundy, A Tangled Web: The Making of Foreign Policy in the Nixon Presidency (Hill and Wang, 1998), p. 239. ↩

-

4

See Margaret MacMillan, Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World (Random House, 2007). ↩

-

5

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 5–7. ↩

-

6

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 10–11 ↩

-

7

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, p. 13 ↩

-

8

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 41–45 ↩

-

9

Montagu’s role as a Soviet spy was revealed by the Venona project in 1963, but MI5 apparently decided that he was not important enough to indict if it meant revealing that the West had broken Soviet codes. ↩

-

10

The ROC finally got to compete in 1985 as “Chinese Taipei.” In 2013, in the men’s doubles final, their team beat the Chinese for their first gold. ↩

-

11

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 106–125, 129–132, 142. ↩

-

12

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 142, 145–147. ↩

-

13

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 151–161, 190. ↩

-

14

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 188–192. ↩

-

15

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 194–206. ↩

-

16

Fortunately for the strapped USTTA, before the team entered China they had been informed that the National Committee for US–China Relations would raise funds if there was any question of a return visit. ↩

-

17

This time, the American team that greeted the Chinese team in Detroit was dressed in bright uniforms, looking, according to Griffin, “like the crew of a cruise ship.” ↩

-

18

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 261. ↩

-

19

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 262–266. ↩

-

20

Griffin, Ping-Pong Diplomacy, pp. 267–272. ↩