President Obama thumped Mitt Romney in the 2012 election by excelling with the voters who are most likely to influence future American elections. Obama won 55 percent of votes by women, who go to the polls in larger numbers than men. The president attracted 71 percent of Hispanic voters and 73 percent of Asians, groups that are growing as a share of the population. Among voters under thirty, Obama won 60 percent. Romney, on the other hand, did very well with older white men. The 2012 race looked winnable for Romney at times because of persistent high joblessness. Yet not only did he lose, he delivered to the Republican Party a bleak forecast of its prospects.

A month after Election Day, Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus commissioned a report about what had gone wrong. The study’s authors did not cite Fox News by name, but they made clear that they thought the network’s polemical programming aimed at the Republican base was a major part of the problem. “The Republican Party needs to stop talking to itself,” they wrote. “We have become expert in how to provide ideological reinforcement to like-minded people, but devastatingly we have lost the ability to be persuasive with, or welcoming to, those who do not agree with us.”

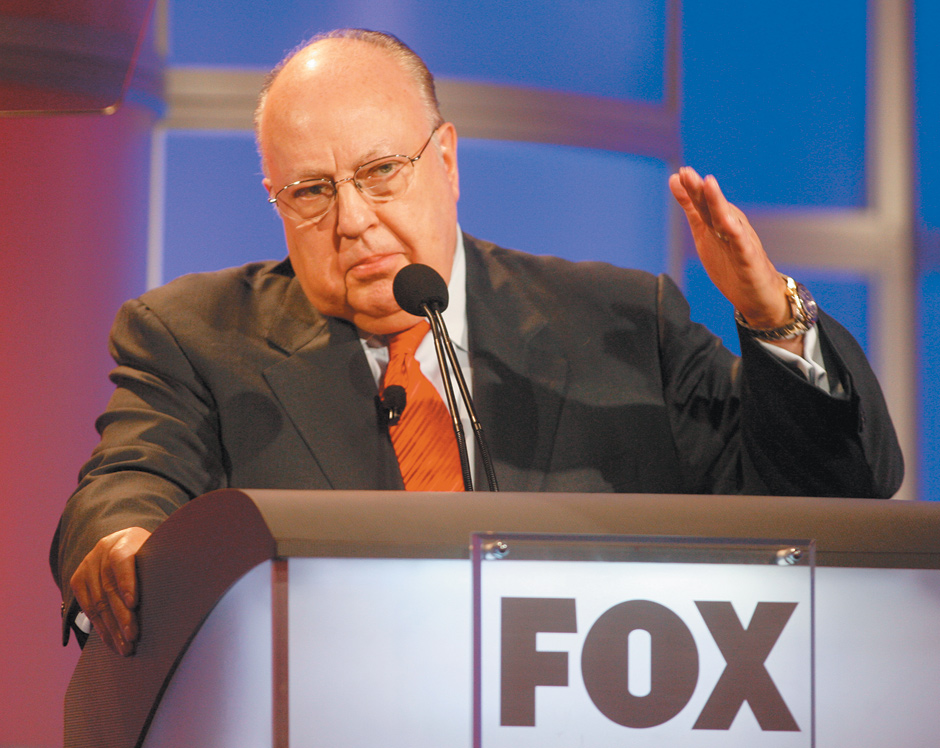

Since its creation in 1996, as an arm of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire, News Corporation, Fox News has made a killing by providing ideological reinforcement to like-minded conservatives. Although the audience for Fox News is aging and leveling off in size, it remains the largest of any cable news network in America by far. The network’s profits in 2012 were just under $1 billion, according to the Pew Research Center. Its profit margin has been above 50 percent in recent years, a rate almost unheard of in mainstream business. Fox’s success has been due in no small part to the insights of Roger Ailes, a former Republican media and campaign consultant and the network’s first and only president, who is the subject of the journalist Gabriel Sherman’s thoroughly reported biography, The Loudest Voice in the Room.

Particularly during the George W. Bush administration, Democrats loathed Ailes because they feared he had devised a propaganda-inspired communications strategy at Fox News that might assure long-term Republican hegemony. There was some basis for this anxiety. By Sherman’s telling, for example, Ailes had a significant and self-conscious part in publicizing the “Swift Boat” smear ad against then Senator John Kerry during the late stages of the 2004 presidential campaign, an ad that purported (through falsehoods) to challenge the senator’s account of his wartime service in Vietnam. More recently, however, following two consecutive presidential defeats, at least some Republican elders have apparently come to view Ailes as a kind of Frankenstein monster that must be subdued and reprogrammed.

Sherman endorses the view that Ailes and Fox News helped to blow the 2012 election for Republicans. Fox News employs plenty of solid, enterprising reporters who play it straight, but Ailes’s overall formula relies heavily on opinion-talk shows in prime time, which are polemical by design. The network’s most popular evening hosts, Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity, celebrated Tea Party radicalism. Another highly popular host, Glenn Beck, who left the network in 2011, promoted conspiracy theories about creeping world government. Even the news coverage gave heavy airtime to disquieting Republican figures such as Sarah Palin and former pizza executive Herman Cain.

In Sherman’s account, Ailes was personally responsible for this ill-conceived strategy. At seventy-two years old, wealthy and isolated, the Fox chief had apparently reached the conclusion that President Obama was driving the United States to ruin. Ailes therefore insisted that Fox News promote an idiosyncratic narrative of America-in-danger. In this story, the country was beset by runaway government power, rising racial conflict, hostility toward Christianity, and out-of-control immigration. But the voters, it turned out, were more concerned with job creation, levelheaded governance, and some measure of accountability and equity after the worst recession in seventy years.

Ailes understood that if the GOP wished to win the White House in 2012, the party should nominate a moderate-sounding candidate. He tried privately to recruit New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and General David Petraeus. Yet these pragmatic instincts proved to be “at odds with the vivid political comedy Fox often programmed,” as Sherman puts it. In the end, the 2012 election was a case of “Ailes being unable to put his party’s goal of winning independents ahead of his personal views.”

Is this really the best way to understand the relationship among Ailes, Fox, and the Republican Party, looking toward 2016 and beyond? It is certainly true that Fox News’s aging and heavily white audience—and the relentless attacks on President Obama that seem to most excite that audience’s emotions—have contributed to the electoral isolation of the Republican Party. Sherman describes Karl Rove, who masterminded George W. Bush’s campaigns in 2000 and 2004, barking at Ailes:

Advertisement

Why are you letting Palin have the profile? Why are you letting her go on your network and say the things she’s saying? And Glenn Beck? These are alternative people who will never be elected, and they’ll kill us.

Yet Rove surely knew the answers to his own questions. Fox is first and foremost a media business. The network has become enamored of “vivid political comedy” while building its formidable profit machine. To map Fox News’s power in American media and politics, it is essential not only to understand Ailes’s role, but also to follow the money.

Roger Ailes was born in 1940 and grew up in a small Ohio town. When he was a boy, his father beat him viciously with a belt to discipline him, even though Ailes suffered from hemophilia and could conceivably have died from any bleeding wound. Sherman quotes Ailes’s brother Robert about their father: “He did like to beat the shit out of you with that belt. He continued to beat you, and he continued to beat you…. It was a pretty routine fixture of childhood.” As an adult, perhaps unsurprisingly, Ailes has exuded a portentous, Dreiserian air. By Sherman’s account, he displays a fierce temper around the office, holds grudges, and regularly vows vengeance against his enemies.

Ailes began his career in television at The Mike Douglas Show and later worked as a Broadway producer. (He flopped with Mother Earth, which Sherman describes as a “trippy, environmental-themed rock musical,” but later succeeded with a production of Lanford Wilson’s play The Hot L Baltimore.) Ailes’s greatest talent, however, proved to be for providing advice to older, Luddite Republicans about how to use television to influence voters. He exercised this ability first on behalf of Richard Nixon in 1968. Ailes sold himself with a memo to Nixon’s aides. “Television is a ‘hit and run’ medium,” he advised. During political debates and talk shows, “the general public is just not sophisticated enough to wade through answers.” Nixon should therefore use “more descriptive visual phrases” and end his statements with “kickers.”

With some trepidation, Nixon’s team gave Ailes a job. He was then only twenty-eight. After Nixon’s televised debate calamity during the 1960 campaign, television understandably intimidated him; a young adviser brimming with confidence and full of piquant instructions might, so the thinking went, help the candidate decode the medium’s mysteries. Ailes may have helped Nixon perform better before the cameras but he did not play a decisive role in the campaign. His shrewdest move was to cooperate quietly with the journalist Joe McGinnis on what became the best-selling book The Selling of the President 1968. McGinnis’s portrait of Ailes as a manipulator of public opinion aroused that age’s anxieties about television’s potential for subliminal suggestion.

After Nixon’s victory, Ailes leveraged the reputation McGinnis’s book gave him to win political consulting contracts. He never entered Nixon’s innermost circle but he became successful advising and creating attack ads for other Republicans. The talent Ailes showed at the time was similar to the talent he later displayed at Fox News. He was willing to go to extremes when others might hesitate, yet he also had a sense of humor and an intuitive ability to meld political messaging with popular entertainment.

Briefly, during the 1970s, Ailes ran a nascent television network funded by the ultraconservative brewer Joseph Coors. The plan was to target Americans who distrusted the news broadcasts on the three major networks. The enterprise failed because in that era, before cable television’s spread, Coors and his partners could not figure out how to reach enough American TV sets to make money.

That frustration forecast the importance a multichannel TV world would hold for conservative media. Some Republican strategists understood that when cable technology arrived eventually and delivered many more options to American households, it would finally provide their ideological camp a chance to control and distribute their own news broadcasts. But at the time of the aborted Coors network, this was still a futurist’s vision. Sherman quotes a “prescient” memo prepared in 1973 for White House chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman. It predicted that it would take “ten years or so” for cable technology to have “significant impact” on the number of television channels available in American homes. That forecast proved to be about right.

A limitation of Sherman’s biography is that he makes too many breezy claims about Ailes’s singular importance—that Ailes became “effectively the most powerful opposition figure in the country” during the Obama administration, or that “more than anyone of his generation, he helped transform politics into mass entertainment.” Such hype isn’t necessary; Ailes is a fascinating subject, and plenty important. It does not detract from the relevance of Sherman’s work to acknowledge that Fox News’s rise to power was ultimately due less to Ailes’s genius as a programmer than to the wider success of cable television.

Advertisement

During cable’s formative, analog years, most providers could deliver only about thirty channels to a home. (The digital cable era of five hundred channels that we know today arrived after 2000.) Ted Turner grabbed the first cable news franchise and named it Cable News Network. ESPN and MTV were other big early successes. As cable reshaped the economics of television, Ailes signed on at NBC, to help guide that network’s investments. But he soon lost a byzantine power struggle. One factor was NBC’s decision to back an upstart network, MSNBC, that Ailes would not control. Ailes departed with a $1 million severance payment. Two weeks later, early in 1996, he joined Rupert Murdoch at a press conference to announce the launch of Fox News. It was a moment of revenge for Ailes, a motivation on which he plainly thrived.

The big question facing Fox News at its launch was whether it could win access to enough American TV sets to be workable—whether, that is, it could overcome the problem that had doomed the Coors channel earlier. Murdoch had to negotiate for access with monopolistic cable owners. A popular programmer such as ESPN had leverage in such talks. But an unproven network such as Fox was in a weak position. This proved to be a dilemma made for Murdoch’s audacity. Normally, cable companies paid programmers for the right to carry their content. Murdoch upended that arrangement and offered to pay cable operators if they would help him launch Fox News. In late 1996, Murdoch paid an unknown amount, rumored to be about $200 million, to cable mogul John Malone to launch Fox News on Malone’s cable systems—at MSNBC’s expense, as it turned out. At the time, the deal seemed like it might be a crazy waste of Murdoch’s money. In retrospect, it looks like a steal. As Sherman writes with some understatement, “Murdoch’s distribution coup put wind at Ailes’s back.”

Sherman gives Ailes great credit for presiding over Fox’s eventual ratings success. Indeed, Ailes learned from CNN’s errors, and Fox’s ratings surpassed those of its rival within just six years. Ailes had several insights. First, he took note of opinion surveys documenting the large number of Americans who distrusted CBS, NBC, ABC, and CNN as left-leaning. Ailes targeted this disaffected audience with marketing slogans that pandered to the viewers’ sense of themselves as truth-seekers: “Fair and Balanced” and “We Report, You Decide.”

Second, by scheduling provocative conservative talk shows in prime time, Ailes constructed an audience that would tune in even when the news cycle was quiet—in between wars, natural calamities, and presidential elections, which were CNN’s specialty. Third, Ailes avoided overpaying for established on-air stars and instead built his own roster of talent from within, which he could shape according to his own sensibility and political proclivities. Finally, the Fox chief had a few tabloid showbiz ideas for cable news that seemed novel at first, such as his unabashed preference for platinum-blond anchorwomen and his deployment of a news ticker—a “crawler”—across the bottom of the TV screen.

Yet the fundamental programming ideas behind Fox News were not original. They were derived from the many precedents of conservative and populist heartland talk radio in America. Commercially successful, populist news-talk broadcasts in the United States dated back to Father Charles Coughlin, who built an audience of tens of millions of listeners during the 1930s by railing erratically against the New Deal. More recently, conservative radio hosts such as the sonorous Paul Harvey had also built very large followings. The biggest stars Ailes hired and promoted at Fox News—O’Reilly, Beck, and Hannity—all had roots in conservative talk radio on the AM dial. If Ailes and Murdoch hadn’t created Fox News, someone else would have adapted conservative radio’s proven formula to cable television.

Toward the end of Fox News’s first decade, the spread of five hundred-channel cable systems further rewarded niche programming, especially if it inspired passion and strong identification within its audience. The same programming model that eventually made the NFL Network and the Food Network so successful also rewarded ideologically homogenous news channels. It didn’t necessarily matter if a network’s audience was large, as long as it was emotionally committed to a subject.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Fox News’s business model is how its audience’s passion shapes and lifts the network’s profits. Normally, when a media company has an audience as old as Fox’s—the network’s median audience age is more than sixty-five—the business struggles financially. That is because younger people buy the most consumer goods and so advertisers prefer them. But Fox News does not make most of its money from advertising. About 60 percent of its revenue—more than $1 billion annually, or about the entirety of its reported profit—comes from fees paid by cable companies for the right to carry Fox News programming, according to Pew. Cable operators who pay these fees don’t care so much about whether Fox’s viewers are young or old; they care more about having viewers who are addicted enough to what’s on cable TV to fork over monthly subscription fees.

The Fox News audience’s fervor also assures that if a cable company ever tried to throw the network off its system, or reduce programming fees, the operator could expect intense, politicized protests. Call this a kind of extortion, or call it leverage in a market economy, but as a result Fox News today receives from the fees paid to it about ninety-four cents per cable subscriber per month, one of the highest rates in the industry, a third greater than what CNN receives and more than double what MSNBC gets. Fox’s high fees are mainly attributable to its superior ratings, but as the industry analyst Craig Moffett told The New York Times last year, the “level of passion and engagement” within Fox’s following has also lifted its revenue because such intense devotion is not easy for cable operators to find.

Here lies the problem in the alliance between Fox News and the Republican Party that Ailes has constructed. Fox owes its degree of profitability in part to its most passionate, even extremist, audience segment. To win national elections, the Grand Old Party, on the other hand, must win over moderate, racially diverse, and independent voters. By their very diversity and middling views, swing voters are not easy to target on television. The sort of news-talk programming most likely to attract a broad and moderate audience—hard news, weather news, crime news, sports, and perhaps a smattering of left–right debate formats—is essentially the CNN formula, which Fox has already rejected triumphantly.

According to Sherman and to an earlier book, based on interviews with Murdoch, by Michael Wolff, Murdoch, Ailes’s boss, has been embarrassed at times by Fox News’s more demagogic talk show hosts.* Yet Fox News is such a cash spigot that Murdoch has been unwilling to impose his reported qualms on Ailes, and has instead extended his contract through 2016. As the chief of Fox News, his compensation runs into the tens of millions of dollars. Karl Rove can yell at Ailes all he wants; Fox News’s profitability and the value it creates for News Corporation is a force distinct from electoral politics.

Toward the end of his book, Sherman chronicles what seem to be Ailes’s emerging Lear years. The wilderness where Ailes wanders is gentleman farmer country north of Manhattan. Around 2008, Ailes and his third wife purchased a weekend home in Garrison, New York, in Putnam County. “All I ever wanted was a nice place to live, a great family, and to die peacefully in my sleep,” Ailes said around that time. Once ensconced in the countryside, he apparently couldn’t help himself, however. He purchased an interest in the local newspaper and launched bitter fights against Putnam politicians over zoning issues.

For all of Sherman’s admirably persistent reporting and the hundreds of interviews he has conducted, there is something about Ailes’s character that remains elusive in his pages. Ailes comes across as both profoundly angry and whimsically charming, darkly driven and creatively humorous; it is difficult for a reader to arrive at an accurate balance of these forces. At one point, while lobbying a local politician in his office, Ailes tosses down printed charts on a desk and declares, apropos of nothing in particular, “What do you think of that?… Fox is outperforming any other cable news network!”

“Well, there are a lot of stupid people out there,” the politician replies.

“Ha!” Ailes answered. “A friend of mine said that, too.”

The lifelong entertainer in Ailes seemingly recognizes that his principal genius might just be showbiz, yet the fierce partisan in him takes excited pleasure from fighting Democrats, regardless of the issues. And increasingly, the ersatz Ayn Rand ideologue lurking somewhere in Ailes’s inner life seems to have guided him toward the belief that market capitalism and America are in grave danger. Only the United States could have produced such a figure at the heart of its political and media culture.

Someday there will be an end to Ailes’s leadership at Fox News, whether it is after the 2016 election or later still. It is tempting to imagine, as Sherman seems to believe, that Fox News’s achievements and those of Roger Ailes are inextricably linked. In fact, it seems more likely that the network’s profitability from programming fees, coupled with the timeworn power of conservative talk, will ensure the channel’s influence for many years to come. Resentments of taxes, of immigrants, of the expansion of government, and of the acceptance of gay rights are among feelings that run deep in some parts of the American population, and they will not go away. Fox News’s ample cash flow means that the network’s programming leaders after Ailes will have lots of money to invest in new ideas, new technologies, new charismatic hosts, and to target younger viewers. Such innovation might ultimately aid the Republican Party much more effectively than Ailes has done. In any event, Democrats have a long record of underestimating Fox News and its audience.

If Fox News’s power is at risk, it is because cable television is at risk. Free news over the Internet destroyed newspapers’ quasi-monopoly position. Similarly, the expansion of online entertainment networks such as Netflix and Amazon might break up the fiefdom of cable sooner than many expect. Brian Roberts, the chief executive of Comcast, the largest cable company in America, which is trying to buy another large provider, Time Warner Cable, predicted recently, “I believe television will change more in the next five years than in the last fifty.” According to this prediction, viewers may switch in huge numbers to the likes of Netflix, in order to watch their favorite shows over mobile smart phones and tablets. Roberts’s forecast is self-serving because it can be used to justify Comcast’s gobbling up of Time Warner. Yet it is hardly a fantasy. The collapse of cable’s position because of Internet-enabled television could erode the political power of Fox News just as rapidly as cable’s triumph enabled it to gain influence less than two decades ago. In this era of disruptive computing power, most media successes are fleeting.

Roger Ailes has always seemed comfortable with such disruption. He certainly has not led a complacent or sentimental life, as he seems well to recognize. “I don’t care about my legacy,” he said after Obama won reelection in 2012 and Fox took some of the blame. “It’s too late. My enemies will create it.” To another interviewer, Ailes conjured his own funeral: “The eulogies will be great, but people will be stepping over my body before it gets cold.”

-

*

Michael Wolff, The Man Who Owns The News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch (Broadway, 2008). ↩