The US spends much more per person on medical care than any other country. And yet, by commonly accepted measures of the quality of its national health system, it ranks only in the middle of the other advanced countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor argue that this “American health care paradox” is resolved when expenditures on other social services that undoubtedly contribute to improved national and personal health are taken into account. These expenditures include support for such services as housing, education, maternal and child care, disease prevention, nutrition, environmental safety, and unemployment benefits. They also involve subsidies for the very poor, the disabled, and the elderly.

The US spends a much smaller percentage of its GDP on these programs than other OECD countries. Thus, when these expenditures are added to what is spent for medical care, the total, expressed as a percentage of GDP, places our country in the middle of the other OECD countries. That is consistent with the ranking of our health care system, and so the authors claim the “paradox” is resolved.

To increase the quality of our health care system to the level now achieved by France, Germany, Switzerland, and Sweden, we would need not only to expand our investment in other social services, but also to practice what Bradley and Taylor call “a more holistic approach” to the medical care of each patient. That means more attention to preventing illness and to modifying patients’ behavior in ways that promote health.

Their argument has intuitive appeal, made even stronger by the warm endorsement given by Dr. Harvey Fineberg, outgoing president of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences, in the foreword he has written for the book, and by recent reports from committees of the IOM. It is generally agreed that poor and disadvantaged populations, such as teenaged single mothers and their children, or unemployed, uneducated, and ill-housed minorities, suffer relatively poor health. So it might seem entirely reasonable to conclude with the authors that the answer to what ails our national health system lies in paying more attention to social welfare programs, preventive measures, and education. Their argument is made more attractive by their clear prose and by their many helpful descriptions and historical explanations of US health care policy. Nevertheless, it does not persuade me, and I don’t believe it will satisfy many critics who look closely at the issues.

In the first place, Bradley and Taylor pay insufficient attention to the great value Americans place on the immediate diagnosis and treatment of personal illnesses and injuries, as compared with public measures to enhance national health such as disease prevention and nutrition. In the US, prompt medical care is given far greater priority than improved public health, and it commands much greater resources. Research on personal medical care is also given a high priority, but new large investments in social welfare programs are not a legislative or political necessity now or in the foreseeable future, so long as conservative Republican opposition to governmental spending of this sort persists.

Moreover, the long-range economic benefits of social welfare and preventive measures are generally misunderstood. For example, prevention of heart attacks in early life through exercise, better diet, and elimination of smoking would extend life into later decades. That is certainly a desirable goal, but then the multiple incurable disabilities of old age and the need for long-term care after retirement begin to increase total health costs.

Second, the evidence presented by Bradley and Taylor to support their claim of resolving the American health care “paradox” is not as strong as their rhetoric implies. This is well illustrated by their Figure 1.3, which shows aggregate health care and social welfare spending in OECD countries for 2007, and is supposed to demonstrate that when all costs are considered, the US is no longer as inferior to European countries as many have claimed. The figure shows that American total expenditures place it just about in the middle of all the countries shown, in accord with the quality of its health care system.

Nevertheless, while total expenditures on health and social welfare in France, Sweden, Switzerland, and Germany exceed those in the US (which would be expected given their generally superior health systems), the figure shows total expenditures for Canada, New Zealand, and Australia to be well below those in the US, even though these countries are widely acknowledged to have better health systems than the US. Similarly, total expenditures in Norway are roughly equal to those in the US, although the Norwegian national health system is generally recognized to be of much higher quality.

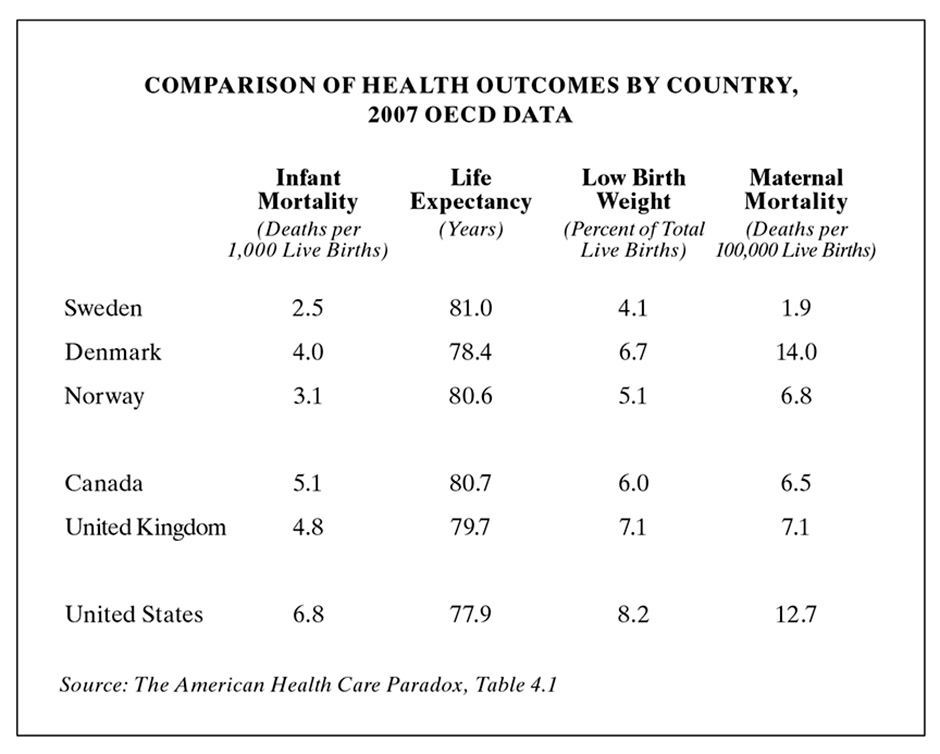

Their Table 4.1 (see below) also illustrates this lack of congruence between health care outcomes such as infant mortality and life expectancy in selected countries and their ranking in total expenditures (as shown in Figure 1.3). In short, total expenditures (social welfare plus medical care) do not seem to be as consistently related to health outcomes as Bradley and Taylor would have us believe. But they are certainly correct in arguing that in general, more attention to welfare programs would improve the quality of life in the US.

Advertisement

My final reason for skepticism is the authors’ dependence on personal interviews with a selected and limited number of sources for much of their original data on attitudes about health care. Bradley, the senior author, is a professor of public health at Yale; Taylor was trained in public health and medical ethics. They would therefore be expected to use the methods of descriptive social science in developing their arguments. They state that they conducted interviews with “more than eighty health and social policy experts, researchers, practitioners, and consumers.” Anyone who has been involved in such interviews knows how variably the results can be interpreted. Bradley and Taylor were commendably diligent in recording and transcribing their interviews, but they took a relatively small sample, and much of it was limited to Scandinavian countries, which are very different from the US, for example in their levels of taxation and their guarantees of medical care and public welfare generally. As a result, the reader can never be quite sure how comprehensive and balanced a picture this book presents of the American health system, when compared with other OECD countries.

Nevertheless, it is hard to deny two basic and fairly obvious points the authors want to make. First, inadequate social services in the US contribute to our poor national health. Second, adding welfare expenditures to those of medical care does help to some extent to resolve the American “paradox” of high medical expenditures and relatively poor health outcomes. But the resolution is not as complete or convincing as claimed, and there is no evidence that expanding welfare programs, as Bradley and Taylor argue, would more effectively improve national health than directly reforming the payment and organization of medical services.

In fact, the evidence suggests the contrary. The US currently wastes vastly more resources on a dysfunctional medical care system than it would ever consider spending on social welfare, so the likelihood of bettering national health through major expansion of welfare programs is remote. As difficult as it may be, trying to reform the medical system is a better bet; this would free up resources that could be used to improve other social services. In addition, most Americans will inevitably become ill or injured at some time in their lives, no matter how adequate the US social services, and for them at that time, a good medical care system is essential. Therefore, it makes sense to consider how reforming the payment and organization of medical care could reduce the heavy burden of unnecessary waste, fraud, and bureaucratic overhead on our medical care system. This looks like the best way to begin to resolve this book’s “paradox.”

There is widespread and growing recognition that the best way of improving the delivery of medical service and reducing its costs would be a shift away from fee-for-service payment for medical care after it is received to prepayment for comprehensive care. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) attempts to move in this direction by establishing “accountable care organizations” that are paid small bonuses for bettering the treatment of Medicare patients (as defined by government guidelines). However, these organizations work mainly through private insurance plans, which, despite these intentions, still pay for the more expensive special procedures and services by fee-for-service. The ACA is therefore not likely to control national health expenditures in the long term. Government actuaries and budget officers predict that these expenditures will continue to rise at an unsustainable rate unless there is major reform.

To achieve better quality at lower costs, I believe we will have to progress beyond the ACA, and the needed reforms will require more participation by the medical profession. Physicians will have to join medical groups that accept a single payment for comprehensive care and are willing to be paid mainly by salaries rather than the fees they bill and collect. Although insurance companies will lobby hard to maintain their power, such a system does not need private insurance plans; it would be much better without them. Vast overhead expenditures would be saved if payment were to come from a single tax-supported agency. That’s why single-payer plans are getting increasing attention these days.

Recent changes in the medical care system have created forces that both favor and inhibit the development of a single-payer arrangement. Physicians who would formerly have started practicing solo or in small partnerships are rapidly becoming employees of large groups in order to avoid the daunting economic risks of managing their own practices. Unfortunately, most of these large groups are owned by hospitals that are primarily interested in furthering their own financial goals. They use their physician employees to generate more admissions and greater use of hospital-based procedures. They want to defend the status quo and their own income, rather than press for reform.

Advertisement

An awakening interest in political affairs and a recent trend toward a preference for Democratic political candidates suggest that the medical profession may soon wish to turn national health policy in a different direction. No large-scale health reform is likely without broad support by physicians, so their political awakening may be the most important factor in bringing about major change. A united profession could influence the views of its patients, and this in turn could influence legislators even more than the money of an army of lobbyists. Legislators need votes most of all, and patients are the voters they need.

Another recent change that may favor the arrival of single-payer health care is the rapid increase in the number of women in active medical practice. They will soon equal or outnumber men. Women physicians seem to be more interested in the social services that are available in multispecialty medical group practices, among them adequate child care and parental leaves. They want to share practice responsibilities, and they tend to have more liberal political views than most men. This major demographic shift in the physician population, as well as its political movement toward more progressive policies, might put the profession in the forefront of health reform instead of the sidelines where it has usually been.

Without leadership by physicians, it is unlikely that we will see any major change in the system for payment and organization of medical care within the next decade or two. And without such change, the future of the American health system is bleak; either market forces or intrusive government regulations (or both) will control how physicians practice their profession. Financial responsibility for health care coverage will increasingly fall on individuals, because neither government nor business employers will be able to afford the rising costs.

The greatest opportunities for reducing unnecessary costs and improving the quality of the American health system are to be found in reforming the payment and organization of medical care rather than in expanding social welfare programs. Although these programs are of enormous importance for many reasons not only related to health, and well worth expanding, they cannot substitute for improving the effectiveness and efficiency of medical care for the sick and injured. That is where we are likely to see the most hopeful future developments.