“China! China! China!” That is how a former Japanese diplomat summed up his country’s foreign policy preoccupations this summer in Tokyo. A quick glance at what’s on sale at Japanese bookstores proves him right: pile upon pile of books about the “threat” of China, the “power” of China, China’s “hatred” of Japan, the “downfall” of China, the “triumph” of China, and so on.

Smaller but still considerable piles of books in a market that is struggling like everywhere else concern a subsidiary branch of the China obsession: books about the awfulness of Korea, for sucking up to China and for hating Japan. There have even been reports of demonstrations here and there of Japanese screaming: “Death to the Koreans!”

Relations among the countries of East Asia are tense, to be sure, with Chinese and Japanese military planes stalking one another over disputed islands in the East China Sea, and the South Korean President Park Geun-hye refusing to talk to the Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo because of territorial (more little islands) and historical quarrels. It cannot be easy for Japan, which had become so used to being the wealthiest, most dynamic, most modern nation in Asia, to see China’s power grow by the day. A younger generation of Japanese, tired of being told by foreigners to feel guilty about a war most of them know very little about, appears to be receptive to a dose of nationalist reassertion.

And so the second administration of Abe Shinzo (the first lasted only one year and ended rather shamefully in 2007) would seem to have arrived at just the right time. Reelected in a landslide in 2012, Abe promised to revive the lackluster economy, and also to be a tough nationalist. There would be no more apologizing for the past or kowtowing to foreigners. Abe vowed to “take back Japan.”

This meant, for one thing, that in 2013 he would visit Yasukuni Shrine, where the souls of soldiers who have died for the imperial cause, including war criminals, are remembered. He would revise the postwar pacifist constitution, written by Americans in 1947 (in rather poor Japanese) to take away Japan’s sovereign right to wage war. A new secrecy law has been passed, making it a punishable offense to leak state secrets or to publish them. There were plans to review apologies made by former Japanese governments for what was done in World War II—plans that ran into such opposition abroad and in Japan that they had to be abandoned.

Some of Abe’s cronies have openly questioned Japanese war guilt. Hyakuta Naoki, a board member of the national broadcasting company NHK, has stated that the notorious Nanking Massacre of 1937, when at least tens of thousands and probably many more Chinese were brutally murdered by the Japanese, never occurred. The head of NHK, Momii Katsuto, has argued that the systematic use of Koreans and other foreign sex slaves in Japanese Imperial Army brothels was an entirely normal enterprise. Few are in doubt that these views reflect those of the prime minister himself.

No wonder, then, that the South Koreans are upset, and the Chinese are warning the world, for their own self-serving reasons, naturally, that Abe is about to revive Japanese militarism. In fact, Abe has never gone that far. But his stated goal has consistently been to change the postwar order, to restore full Japanese sovereignty and national pride. Not only does he want to do away with official pacifism; he also wants to give young Japanese a new sense of patriotism. The so-called “Tokyo Trials View of History,” used to promote pacifism by recalling Japan’s dark wartime past, is dismissed by Abe’s followers as left-wing propaganda. It is time for a national reawakening, a new beginning.

All this would indeed be alarming if Abe’s program weren’t so riddled with contradictions. For even though he loudly proclaims his intention to overturn the postwar order, the main pillar of that order is still very much intact. As a result of its pacifist constitution, Japan is highly dependent on the US for its security. This would be the first thing one would expect a Japanese nationalist to want to change. And some do. The former governor of Tokyo, a right-wing popular novelist named Ishihara Shintaro, for example, makes no bones about this. “Taking back Japan,” he said, “should mean absolute independence.”

But Abe has shown no such intention. Since he cannot get the requisite two thirds of the Japanese Diet to agree to constitutional change, all Abe has achieved is a “reinterpretation” of the constitution, allowing Japan to help friendly troops or United Nations peacekeepers in case of an attack, and only when specifically asked to do so. Even as he huffs and puffs about taking back Japan, Abe has done everything in his power to tighten Japan’s relationship with the US, in security and trade; he is a champion of the “Trans-Pacific Partnership,” which includes Japan, the US, and ten other countries. Even the law protecting government secrecy came about after the US exerted pressure to safeguard shared intelligence. Far from wanting more independence from Washington, the main fear among Abe’s conservative advisers appears to be American weakness, the possibility that a war-weary US would not immediately come to Japan’s rescue in case of a conflict with China—over a few disputed rocks in the South China Sea, for instance.

Advertisement

Dean Rusk, who negotiated the US–Japan Security Treaty as assistant secretary of state in 1951, once called Japanese strategy “schizophrenic.” Japan, he said, was like “the man who wanted to sleep with a woman one night without having to say hello to her in public the next day.” What he meant then was that Japan’s eagerness for US military protection sat uneasily with its proud and sometimes moralistic pacifism. The same metaphor could be applied to Japan today, but with a new twist. Now it is Abe’s stated aim of restoring sovereignty that doesn’t quite square with his anxiousness to preserve Japan’s status as a kind of US military protectorate.

For more than 150 years, Japan has placed itself awkwardly between Asia and the West. To understand Japan’s current problems with China, one has to understand its tortured relationship with the US, the first nation to defeat Japan in a war. Not that China’s relations with the US are any more straightforward. The Chinese, feeling hemmed in by unfriendly powers, would dearly like to drive a wedge between Japan and its Western protector. At the same time, China is probably happier with the US as a Pacific policeman than it would be with Japan as a revived military power, even though China is also making a point of defying US policies in the Pacific.

One way to understand postwar Japanese attitudes toward US dominance in cultural, social, as well as military affairs is to look closely at Tomatsu Shomei’s extraordinary photographs taken of American military bases in Japan and Okinawa in the 1960s and 1970s. They have been described as pictures of hate, but that is to miss the deep ambivalence toward the US that was typical of Tomatsu and others of his generation.

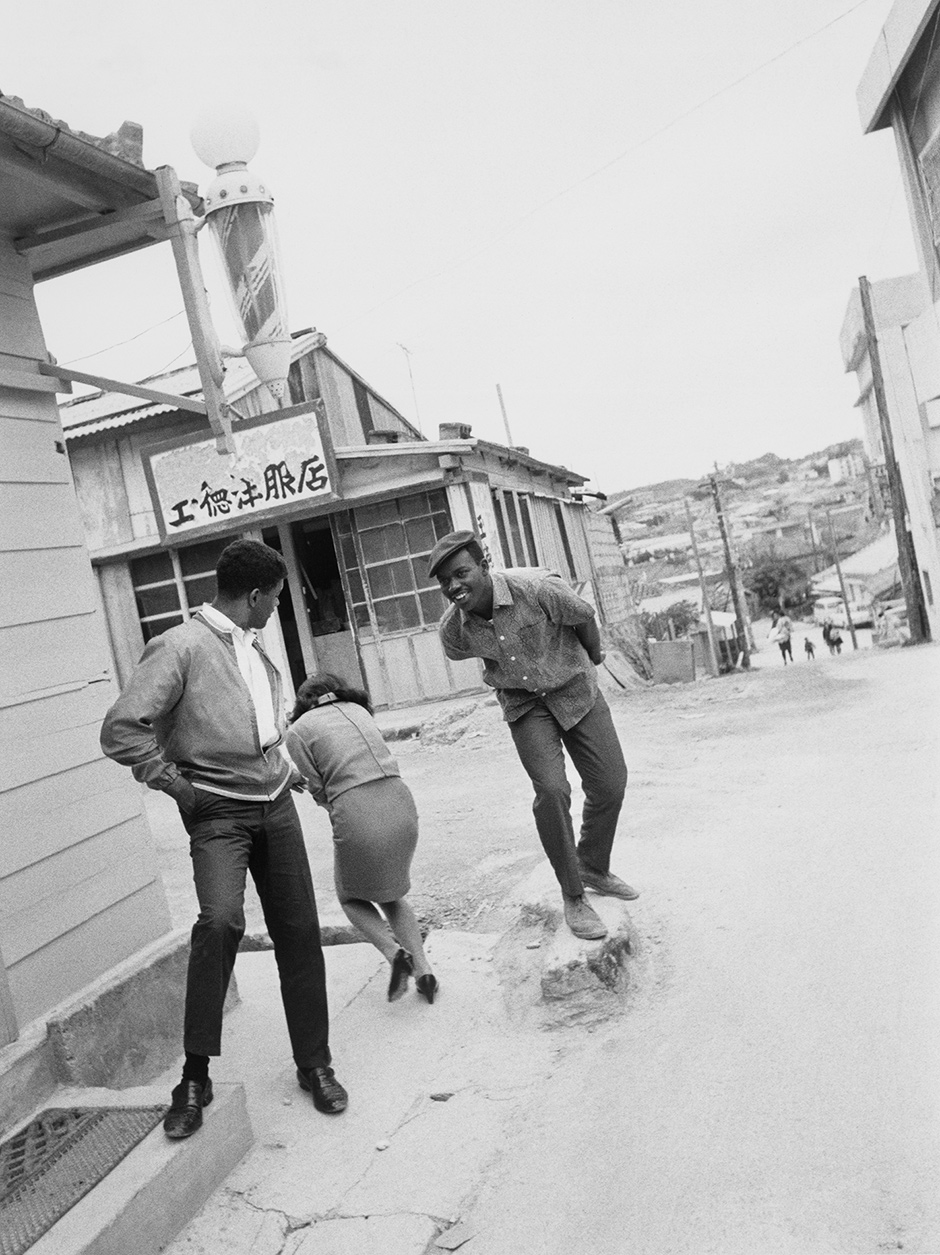

Yes, there is the nasty image, taken from below, of a US army boot about to descend on the photographer’s head, with laughing crew-cut heads peering down, as though they represented the brute force of America stomping on poor wormlike Japan. Or the less contrived and even more shocking image of a B-52 bomber swooping over a steaming rubbish dump in Okinawa with an old woman in rags looking up. But there is also something alluring about the pictures of neon-lit bars in naval towns like Yokosuka, “home of the seventh fleet,” or the black GIs striking Black Panther poses, or even the graphic panache of huge Coca-Cola signs, dwarfing a line of shabby little Japanese umbrellas. The young Japanese men in several photos, mimicking an American fantasy in their cream-colored jive suits and shades, are a little pathetic but also touching. You sense that Tomatsu understood their vulnerability because he shared their fascination. (Chewing Gum and Chocolate, a new compilation of his photographs, has been superbly edited by Leo Rubinfien and John Junkerman.)

All Tomatsu’s pictures were taken after the Allied occupation of Japan (though not yet Okinawa) was long over. Japan became independent again after signing the Peace Treaty of San Francisco in 1951. But for many men of Tomatsu’s generation the occupation was never really over; it continued inside their heads. Occupation was the title he chose for the pictures he took around the US base towns in Japan and Okinawa. Tomatsu was fifteen when Japan was defeated and the US troops arrived, casually tossing sticks of gum and chocolates at the children running after their jeeps. The rampant conquerors, who could often buy the favors of local women with a pair of silk stockings or a Hershey bar, were for young Japanese men a source of deep humiliation. But they also came with jazz music, easy manners, cool clothes, a promise of democracy, and what seemed then like vast wealth. Tomatsu puts it well:

I always say that my Occupation series is on the border between love and hate. I can neither reject nor affirm the occupation. Of course I reject it, but there are many elements that I have to affirm. Immediately after the defeat, some people called the occupying forces an army of liberation. Those words imply an affirmation, and I experienced that very feeling.

For people on the left, including members of the Communist Party, which had been banned by the wartime Japanese authorities, the occupation really was a liberation. Political prisoners were released and trade unions reorganized. Land ownership was radically reformed. Women got the vote. In fact, the new Japanese constitution was a very progressive document. Despite General MacArthur’s own reactionary views, the politics of the early years of American tutelage were those of the New Deal.

Advertisement

That is why Japanese liberals felt so betrayed when the cold war put an end to all this. Love turned to hate when “red purges” took place in unions, educational institutions, and even movie studios. Japan—to the huge profit of the Japanese business elite—was dragged into American wars in Korea and Vietnam. Even as Republicans like Richard Nixon publicly stated that the pacifist constitution had been a terrible mistake, it became a badge of honor for the Japanese left. And in fact mainstream conservatives, who were more than happy to let the US take care of security while the Japanese got on with business, supported official pacifism too. They did not necessarily like the Americans, but they could profit from them.

But not everyone on the right was happy. Ever since the end of the war, a vociferous minority felt not only that Japan had been robbed of its sovereignty, but that a sinister alliance of foreign occupiers and Japanese leftists had destroyed the moral foundations of the Japanese polity, including the sacred imperial institution. Taking back Japan, for them, did not mean being pro-American. Such sentiments are still heard today. Here, for example, is Sugiyama Katsumi, managing director of the Defense Research Center in Tokyo, whose words are worth quoting, not because they represent mainstream opinion, but because they reflect a small but insistent current in conservative Japanese politics:

America’s fundamental strategy towards Japan is containment. For the last seventy years the US has continued to regard Japan as an enemy country. The reason for the continued presence of US troops in Japan is not just because Japan is strategically indispensible, but because it is viewed with the deepest distrust.

Ishihara, the former governor of Tokyo, is of the same persuasion. And Prime Minister Abe’s strident opinions about constitutional and cultural revisions suggest that he is too. In fact, however, his policies show that he is still firmly planted in the conservative mainstream. He would much prefer to be protected by the US, even if that means remaining under Washington’s thumb, than to make independent arrangements with Japan’s immediate neighbors.

And so Abe has to contend with furious demonstrations from people on his left; one middle-aged man actually set fire to himself in protest against tinkering with the pacifist constitution. But he is also attacked from the right for being such a pushover, relatively politely by Ishihara, and less so by extreme right-wing groups whose khaki and navy blue sound trucks drive around Tokyo blaring wartime military marches.

Abe Shinzo is not the first Japanese prime minister to talk about revising the constitution and shaking off the constraints of the postwar order. In fact, history has repeated itself in a highly peculiar way. Abe’s grandfather was Kishi Nobusuke, a wily old fox who was the minister in charge of war industry from 1941 until Japan’s surrender. He was, as it were, the Japanese counterpart to Albert Speer, and as such was arrested as a war criminal in 1945. Without ever being indicted, he was released from prison in 1948 and quickly returned to politics as a conservative nationalist. Once China “was lost” to communism, the US felt it needed every Japanese conservative it could get, even suspected war criminals. But Kishi’s wish to abolish Japan’s constitutional pacifism was not an attempt to revive Japanese militarism. In his view, Japan’s lack of sovereignty in military affairs prevented it from being an equal partner to the US. Kishi was as much of a cold war warrior as John Foster Dulles, Richard Nixon, and Dwight D. Eisenhower, with whom he liked to play golf, but he resented his country’s subservience to Washington, a view he shared with his left-wing critics.

Kishi’s political ally in the 1950s was another veteran of Japan’s pre-war authoritarian politics, Hatoyama Ichiro, who served as prime minister from 1954 to 1956. Hatoyama was not only a constitutional revisionist, he also wanted to forge ahead with an independent Japanese foreign policy by reaching out to the Soviet Union and Communist China. This challenge to the postwar order found little favor in Washington, and Japanese conservatives who prized good relations with the US above all else soon helped to bring Hatoyama down.

Kishi, who became prime minister in 1957, was more circumspect. Like Hatoyama, he was unable to garner enough support in the Diet to change the constitution, so he decided to concentrate on the US–Japan Security Treaty instead. By pressing the Americans to promise to consult Tokyo on military matters, in return for Japan’s active military assistance to US troops in case of an attack on bases in Japan, Kishi sought to win a more equal status for Japan. He thought he might find allies on the left for this venture, as well as among conservative revisionists. So when the US conceded on these points, Kishi touted this as a major diplomatic triumph. He played a round of golf with Eisenhower. John Foster Dulles was happy. And, Kishi thought, the Japanese public surely would be happy too.

But public sentiment had turned so fiercely against US bases, and Kishi, as a suspected war criminal, was so unpopular, that his promotion of a new security treaty with the US made him the target of huge demonstrations in 1959 and 1960. In May 1960, Kishi rammed the ratification of the treaty through the Diet by ordering policemen to remove the socialist members who tried to obstruct the vote. On June 15, a female student died in the crush when riot police clashed with the protesters. On June 22, more than 120,000 people, not just students and left-wing activists but many ordinary citizens too, surged around the Diet. The next day, Kishi had to resign. He had got his treaty, but his public career was over. A month later, he was stabbed six times in the leg with a hunting knife. His assailant was not a left-wing protester, but a nationalist of the far right.

Kishi remained a powerful figure behind the scenes in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, which continued to rule Japan (initially with the help of a great deal of covert American cash) almost without interruption between 1955 and 2009, when the relatively liberal Democratic Party of Japan broke the mold. The man who took over as prime minister was a rather odd-looking bug-eyed figure named Hatoyama Yukio, the grandson of the ill-fated Hatoyama Ichiro. “The Alien,” as many Japanese called him, proceeded to repeat, in a rather clumsy way, what his grandfather had begun.

The new, post-LDP Japan would become less dependent on the US and establish its own arrangements with China and other Asian countries. When the US wished to move a huge marine base from one part of Okinawa to another, Hatoyama dithered under pressure from Okinawan activists and DJP party members who wanted to remove the US bases from Okinawa altogether. And precisely the same thing happened to Yukio that happened to his grandfather. Washington was upset. Japanese politicians and mass media pundits, worried about the possible damage to US–Japan relations, ganged up on him. Others, on Hatoyama’s left, felt that he had not gone far enough. He resigned in 2010.

Prime Minister Abe has not yet been stabbed by a right-wing fanatic, nor has he displayed any of his grandfather’s devious intelligence. And his neo-liberal promotion of free-market economics would not have pleased Kishi, who was an old-fashioned Japanese state interventionist. But Abe is much like his grandfather in one respect: he, too, mixes his nationalist rhetoric with an anxious commitment to please the US in a partnership that is still very far from equal. The promise to mend the ties that threatened to be undone by Hatoyama was one of the reasons for his political return. Now that the LDP is in power once again, after a three-year break, things are pretty much back where they were before.

Some have argued that this is a very good thing, and the US should continue to impose what Robert Kagan has called a “liberal order” on the world by remaining a Western as well as Asian power. In a widely read article in The New Republic Kagan posed the following question:

What might China do were it not hemmed in by a ring of powerful nations backed by the United States? For that matter, what would Japan do if it were much more powerful and much less dependent on the United States for its security?*

This largely rhetorical question would seem to confirm the suspicions of Japanese nationalists, who believe that US troops are in Japan to police the Japanese rather than to protect them. Nor will it do anything to reassure the Chinese who feel, rather like nationalists in Wilhelmine Germany, that other powers won’t let them have their place in the sun. In any case, Kagan certainly implies that other countries, including staunch US allies, cannot really be trusted to act responsibly without the steadying hand of US military force.

That leading figures in Europe and Asia go along with this—for reasons of convenience, or unwillingness to spend more of their own taxes on defense, or simple inertia—should not be read as proof that Kagan’s analysis is right. Kagan’s assumptions are pretty similar to those of many Europeans in the early twentieth century, and sometimes later, who thought that their colonies were far from ready to rule themselves and found it necessary therefore to continue doing their duty as colonial overlords. The problem is that as long as imperial rule persists, the colonies will never be ready to rule themselves.

The US may not be an imperial power in the conventional sense, but it is facing a common late-imperial dilemma. Retreat from East Asia may lead to uncontrollable ruptures, but continuing its dominant role will make it harder for Japan, or indeed China, to find a stable modus vivendi on their own. The current squabbles over small islands, imperial shrines, and memories of history may not seem very grown-up, but that is what you get when countries are treated like children.

-

*

“Superpowers Don’t Get to Retire: What Our Tired Country Still Owes the World,” May 26, 2014. ↩