LuEsther T. Mertz Library, New York Botanical Garden

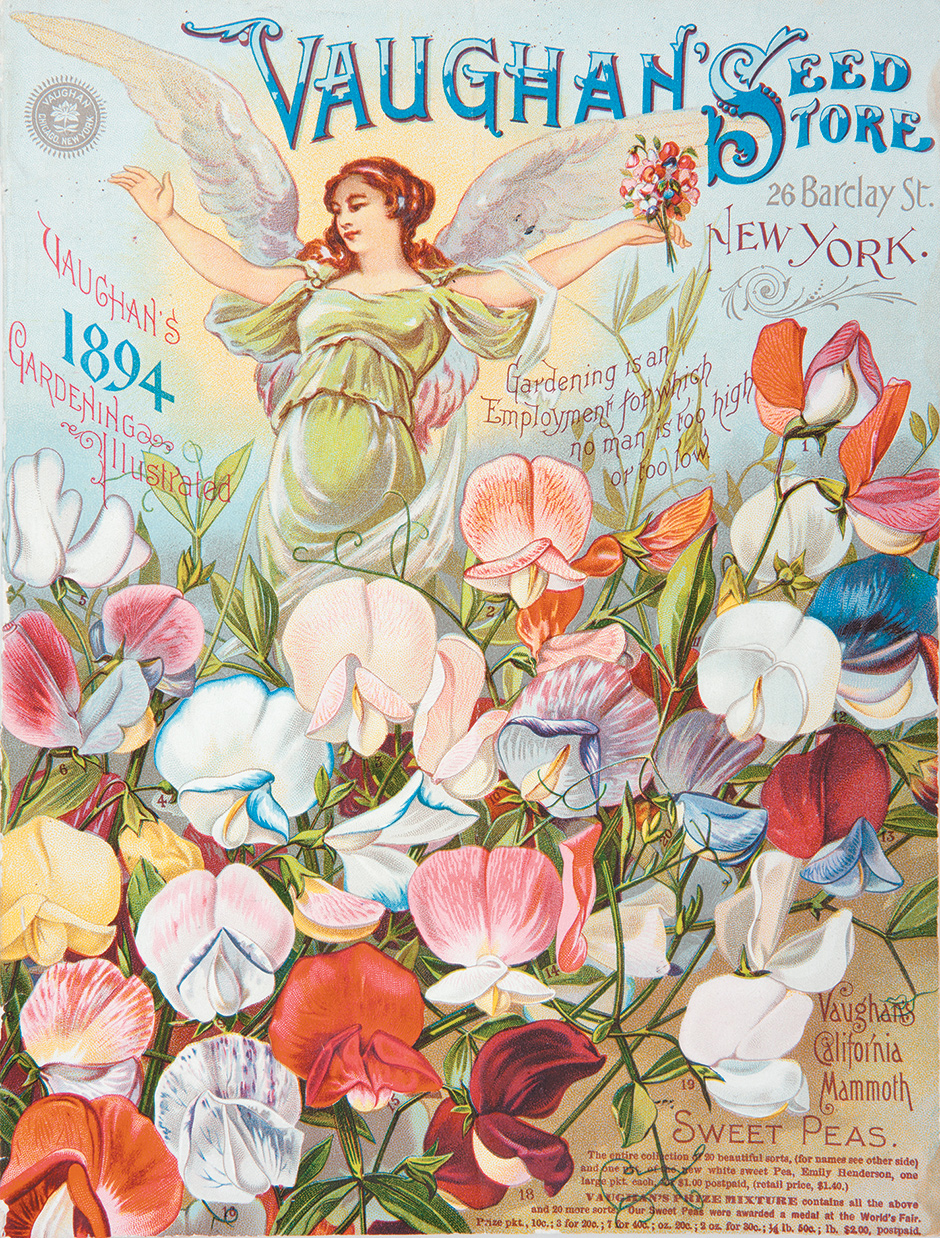

The cover of Vaughan’s 1894 seed catalog, an example of what Elizabeth S. Eustis in Flora Illustrata calls the ‘height of dazzling chromolithography’ of late-nineteenth-century seed catalogs. ‘The appropriation of chromolithography for commercial purposes repelled art critics, but delighted consumers,’ Eustis writes. ‘It remained the preferred embellishment of seed catalogs until color photography began to displace it around 1896.’

Botanical gardens, like film stars, have survived by reinventing themselves. Their persistence has been most remarkable. In America, they are linked to big cities for which, like orchestras and libraries, they are items of civic pride. Up and down France, no fewer than eighty-eight sites still class themselves as botanical gardens or public arboretums. In Germany, they number more than a hundred, including several linked to locally based universities, frequent holders nowadays of the botanical watering can. Much though modernizing university presidents might wish to be rid of heated greenhouses and steamy palm houses, none has yet dared to sell off a botanical garden and spend the proceeds on administration.

Political devolution has been even less of a danger. So far from dismembering “national” botanical sites, it has created more. In May 2000, a brand new National Botanic Garden, funded by the UK Millennium Commission, opened in Wales, after the devolution of powers to a Welsh National Assembly in 1998. Skeptics wondered if its distinctive exhibits would be beds of leeks, the Welsh national vegetable, immortalized by Shakespeare’s Fluellen in Henry V. Almost before leeks could have been harvested, the botanical garden had to be bailed out by a big rescue grant, mostly from the very National Assembly that had championed it. Several more grants have followed. If there is ever a National Botanic Garden of Catalonia, it will have to spend very fast to beat the Welsh track record: three years from inauguration to bankruptcy.

When Americans embarked on botanical gardening, they came late to a long-established genre. Botanical gardens are sometimes said to have begun with Aristotle’s pupil Theophrastus, in Hellenistic Athens, with further speculation that in the first one, he grew new plants sent home from Persia and India by Alexander the Great. Theophrastus certainly had a garden and observed seasonal changes in the plants he grew in it, but his knowledge of plants found by Alexander’s conquests was drawn from books by participants in the campaign. He never himself grew the citron trees whose cultivation in Media he describes so well from other eyewitnesses’ writings. There is no sign that his garden was laid out in any scientific or rationally classified way.

Botanical gardens began in Tuscany in the 1540s on the orders of the Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici. In 1544, the first one was founded in Pisa. In 1545, the Venetian republic started another in Padua. Florence rapidly followed in December of that year. Nowadays, Pisa’s garden is notable for the straightness of the trunks of its nineteenth-century trees, Florence’s for the terra-cotta pots huddled around its Orangery, and Padua’s for the big old palm and ginkgo trees, admired by Goethe in the 1780s, and its symbolic design as a circle inside a square. When founded, these gardens housed medicinal plants, formerly a concern of monastery gardens and still to be seen in some of Padua’s original circle of stone-edged beds.

Utility, knowledge, vanity, and curiosity then helped the botanical model to spread through Europe. As unknown lands became known in the West, botanical gardens became even more wondrous by cultivating some of the newly discovered plants. Onlookers sometimes referred to them as new “Edens” or paradises on earth, but it is unclear that those who actually worked in them saw themselves as recreating the legacy squandered by Adam and Eve.

In fact, many novelties from “new worlds” gravitated to the private gardens of royalty or the rich instead. The duke of Tuscany was proud to grow the first highly scented jasmine from the Far East, but he had it grown in a greenhouse at the private Medici seat, Castello, not in Florence’s botanical garden. By 1600, the most remarkably planted botanical garden was in the Netherlands, the Hortus Botanicus linked to Leiden University. Happily a great plantsman, Carolus Clusius, coincided with the Dutch East India Company, which brought back living plants from the faraway lands it was visiting. Clusius grew and displayed them publicly in the Leiden garden, which has recently replanted much that he brought into cultivation.

In the eighteenth century, the challenge of naming and classifying all these plants took a new turn with a Swede from Uppsala, Carolus Linnaeus. He established the principle of classifying them by their sexual parts. Sex-based classification gave botanical gardens a welcome new role. They could now display the newly arranged families, or “genera,” in special system beds. Their staff could work with great learning on disputed cases of the ordering, or “taxonomy,” of what exactly belonged where. That study continues, exasperating gardeners who find their chrysanthemums renamed “dendranthemums,” an academic fiat that they then ignore.

Advertisement

The nineteenth-century age of Western empires added a wholly new dimension: the display, cultivation, and dissemination of plants from all over an empire’s territories for the edification of the imperialists’ fellow citizens. Heated greenhouses were developed to meet the challenge. Tea and rubber are only two of the crops spread from botanical gardens across the British Empire, transforming local economies and irremediably altering local ecologies whose own trees and undergrowth they drove out. Even the botanical garden itself became transplanted. In 1787, the first one was planted in India, the Calcutta Botanic Garden.

Fourteen years after Calcutta, New York joined the party, receiving its first botanical garden, the Elgin Botanic Garden linked to Columbia College, on the site that is now Rockefeller Center. It lasted there for only sixteen years, but after the landscape planning of Central Park, completed in 1873, the idea was revived. In the 1880s, the newspaper owner and reporter John Mullaly began an audacious campaign for no less than six parks along the Bronx River, of which the “Bronx Park” would have the most naturally favored advantages.

In 1887, Mullaly’s book The New Parks Beyond the Harlem set out his eloquent vision. He wanted landscaped parks with space for “a parade ground, a rifle range, baseball, lacrosse, polo, tennis and all athletic games,” except, sadly, cricket, whose new prominence in London’s Lord’s cricket ground had escaped him. “Nine miles of waterfront” would allow “bathing, fishing, yachting, rowing,” but the Bronx site was special. “No better place,” he saw, “could be selected for a model botanical garden than Bronx Park.” He even anticipated the false dream of so many modern educators, envisaging such a garden as a place where “children could learn without studying, acquire knowledge without opening a book.”

No newspaper columnist has ever done so much for gardening. Mullaly battled for his vision and in 1891 advertisements went out for $250,000 to realize a botanical garden in the Bronx. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers continues the story in her excellent chapter for Flora Illustrata, the superbly produced and color-illustrated book that accompanies a marvelous exhibition in the New York Botanical Garden’s library. It has three interrelated levels. Its main subject is this exceptional library, which is housed in a noble Beaux Arts building, framed by an avenue of soaring tulip trees. The book depicts them as newly planted saplings in 1903. The story of the library’s growth into what is now the LuEsther T. Mertz Library is fascinatingly presented by its current director, Susan M. Fraser. Too few New Yorkers realize that they live in a city with the world’s greatest botanical library, which contains about one million catalogued items and eleven million archival documents, many of extreme rarity and value and all acquired within about a hundred years.

Only six of Flora Illustrata’s eighteen chapters are centered on American landscapes, books, and flora because the library relates to so much elsewhere in the world. The American chapters are the most original, especially a captivating one by Elizabeth S. Eustis that outlines the holdings of brightly illustrated American seed catalogs and much else, otherwise lost to garden history, from the later nineteenth century. She relates the catalogs to their market, a “growth” one in every sense. The seeds were more and more widely traded with the spread of railways, competitive enterprise, and a remarkable relationship with the postal service, which agreed to a special third-class reduced rate for consignments of seeds.

By 1898, one seed merchant, Childs, was sending out one and a half million seed catalogs a year throughout America from the special rail station and post office attached to its premises. Seed production became big business, intensified by the specialization of labor. In the 1890s, in Minneapolis, Carrie H. Lippincott gave it a new twist by employing women only in her seed business. They harvested and packeted the varieties that her catalogs depicted in pastel shades of prettiness. Labor relations in this all-female enterprise would be a fascinating subject if historians could somehow dig into them.

Libraries like New York’s added yet another aspect to botanical gardens’ sense of mission. The gardens already had pressed leaves and flowers, the basis of their big herbaria. Now they could collect books. Here the New York Botanical Garden owed an immense debt to its first and longest-serving president, the visionary Nathaniel Lord Britton. By 1900, he had encouraged two board members, Andrew Carnegie and J.P. Morgan, to set up a fund for exceptional forays into Europe’s book market.

Susan Fraser follows the library’s victories stage by stage, including the acquisition of invaluable books from three Swiss libraries at once in 1923. However, the donors did not only give money. Carnegie even bid personally for items at auction. Repeatedly, gifts have come to the library from established collectors. Outsiders who reduce American philanthropy to nothing but surplus money miss the impulse behind so much of it. Expertise and engagement grow with the giving and help to shape it.

Advertisement

In her chapter on the Bronx garden as “an American Kew,” Rogers credits its early development to three impulses: “reform humanitarianism, the beginning of scientific botany as a professional occupation, and Gilded Age civic pride.” The library, too, is a creation of them. Rogers stops her chapter in about 1938, but the garden, like the library, has been transformed yet again in the past twenty-five years. Readers need to be kept up to date.

In 1989, Gregory Long took on the garden’s presidency. At the celebrations of his twenty-fifth anniversary in June 2014, tributes were paid by a galaxy of New Yorkers, gathered for the ball in his honor in the garden’s conservatory. Under Long’s leadership, the garden’s endowment has gone up nineteen-fold. $650 million has come in for new projects, including the restoration of the great conservatory, the replanting and redesign of more than one hundred acres of the garden, fourteen garden farms fanning out through the Bronx for public education, a fourfold rise in attendance and membership, and very large investments in the scientific mission including the Pfizer Plant Research Laboratory, a facility unsurpassed in the world.

Long’s planning and strategies have been so successful that they themselves have become subjects of study in university courses. To mark his twenty-fifth anniversary, a target of $25 million had been set. $28 million was raised and in thanks, Long’s modest speech referred repeatedly to the “civic-mindedness” of so many of the donors. That term has never been used in my hearing for a donor in London or Oxford.

The tremendous success of Long’s work has come at a time when other great botanical gardens would pine to raise even a quarter of the target for his anniversary. The New York Botanical Garden owes much to a visit in 1888 by Britton to London’s Kew Gardens, the inspiration for his sense of a scientific and horticultural mission. However, while Long and his team have been propelling their “American Kew” ever onward and upward, Kew has been lurching despite its best efforts from one crisis to another. The latest, a gap of £5 million in its yearly budget, was identified in early 2014, causing the directors to announce the inevitable loss of 125 jobs, about a sixth of the garden’s total. A petition, promptly signed by 100,000 protesters, made Britain’s coalition government think twice; its junior partner, the Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg, announced a rescue grant of £1.5 million. It was his only popular announcement all year. Nonetheless, a gap of £3.5 million remains and Kew’s directors insist that the job cuts have to go ahead.

Since Margaret Thatcher abolished Kew’s state subsidy, the price of entry tickets has had to rise two hundred-fold, to £15 per adult. Visitor numbers have continued to rise, thanks to Kew’s increased openness to special events and family-centered attractions. In Germany, Munich’s botanical garden, one of the world’s greatest, charges only €4, thanks to its continuing subsidies. It also offers a garden that has avoided Kew’s checkered recent history. Kew’s worldwide scientific mission remains exemplary, but under the directorships of both Ghillean Prance, the revered expert in rainforests, and Peter Crane, his admirable successor, the garden itself was not a major emphasis. In the mid-1990s, Crane would comment freely, as a scientist, on the waste, in his view, and ecological insensitivity of London’s famous Chelsea Flower Show. Kew’s living heart was considered to be its Millennium Seed Bank, a store for seeds from all the floras of the world, its local conservation in faraway countries, its commitment to “sustainability” and to genetic and “plant-scientific” research. All these concerns have been added to the missions of modern botanical gardens, strange though they would seem to Cosimo de’ Medici. Even their old herbaria may soon come back to life: they are depositories of historic DNA.

However, seed banks and conservation studies are never going to bring in many paying visitors. The mass spattering of Kew’s Broad Walk with brightly colored crocuses for a quick spring fix has been a hasty realization that the garden’s public face needed to be brightened. Meanwhile, Long has been happy to bring his trustees from New York to London for the “world’s greatest flower show,” Chelsea, and to transform the scope and beauty of the New York Botanical Garden, a major element in its many-sided mission.

Long and his vice-presidents for horticulture, including Todd Forrest and the celebrated Francisca Coelho, head of glasshouse cultivation, have made the New York Botanical Garden into a destination that nobody should miss. Its scientific mission continues to grow famously, but the grounds, too, have been transformed at every turn. Among their supporters, a trio deserves a high place on the honor roll of New York’s cultural philanthropy: Enid Haupt (restorer of the garden’s landmark glass conservatory), Shelby White (backer of the new Native Plant Garden that cleverly edits the wild flora of the East Coast), and LuEsther Mertz (the great benefactress of the library and herself an aspiring librarian before her business career). A pyramid of fellow donors supports the garden’s balanced combination of science, learning, art, and horticultural skill. Long’s latest project is an Edible Academy, to teach the skills of vegetable gardening to 80,000 children and their families. It will be one more realization of Mullaly’s ambitions for learning without the opening of books.

None of this mission is easy. The garden’s public grant from New York City has been reduced to less than 15 percent of its annual operating costs. Adult tickets range up to $28, with free admission to the grounds on Wednesdays. The gap is partly filled by a vigorous program of shows, events, and days for specialists in different aspects of gardening. Connections between gardens, art, and literature have brought in crowds. Recent groundbreaking shows have focused on Emily Dickinson’s flowers and poems or Beatrix Farrand and her contemporary women gardeners. They have linked flower shows under glass to literature and art by simultaneous exhibitions in the garden’s library and by apt “poetry boards” displayed along the garden’s walkways.

Plants, after all, are entwined in so much more than agrodiversity. Even the rarest of the library’s old books never hid in isolation. One of its treasures is a copy of Der Gart der Gesundheit, published in Mainz in 1485. It shows flowering plants in their actual growth and shape, rather than their traditional images in woodcuts. By 1505, the Flemish master artist Gerard David was finishing his superb triptych of the Baptism of Christ, still on display in Bruges. The foreground is dotted with identifiable flowering plants, regardless of their varying seasons of flower. Some, but not all, of them have symbolic meanings, but almost all of them appear to have been modeled on the Gart’s illustrations. The garden library holds a key to a picture closely studied by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s curator of European paintings, Maryan Ainsworth, who discussed the link in her catalog of the museum’s exhibition of David’s work in 1998.1 Flowers in paintings are items that gallery captions too often ignore or mistake.

In Scotland, an official report on the “impact” of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, one of Europe’s finest, describes its £11.2 million of public funding to be partly for

the conservation of species, protecting various habitats, supporting sustainable agro-forestry, conserving biodiversity, monitoring climate change and improving rural livelihoods in very poor parts of the world.

New York’s garden would endorse all these estimable aims, but the “garden” risks being lost as only one among other more highly ranked aims that botanical gardens present to their public funders. Edinburgh runs some of Britain’s finest gardens, but its funding, too, faces public cuts, scheduled to fall on the growing of new plants and the much-needed restoration of its outdated greenhouses. Yet the more the gardens decline, the more botanical gardens’ supporters will lose interest. Meanwhile, some of the “very poor parts of the world” have been given a lifeline, not from growing botanically approved indigenous “sustainable” plants, but from growing exotic fruits and vegetables that can be flown cheaply to Western supermarkets.

Why is good gardening not the first priority of good institutions with the word “garden” in their names? There is far more to it than the drab mantra that only “native” plants must be used in “responsible” horticulture. As Carrie Lippincott knew, so many lovely plants in the world can be grown and enjoyed “responsibly” by people taught to sow seeds. Biodiversity may be a fine ideal, but so is that scientific bugbear, beauty. The evanescent beauty of a garden is renewable. It can also be transformative, as visitors to the New York Botanical Garden discover and then wish to perpetuate.

In 1874, supporters of London’s Bible Flower Mission published The Flower Mission, in which, they observed, “flowers had recently been placed as a humanizing influence on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.” Many of the younger stockbrokers are said to have remarked that “the flowers would remind them of the green fields of their youth, and of the days when they were young and innocent.”2 Not only those “very poor parts of the world” need urgent attention. A stay in Long’s superb botanical garden might help to avert Wall Street’s next moral crisis.

This Issue

January 8, 2015

In Ferguson

A Better Way Out

Who Is Not Guilty of This Vice?

-

1

Maryan W. Ainsworth, Gerard David: Purity of Vision in an Age of Transition (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 231–232. ↩

-

2

The Flower Mission (London, 1874), cited by Mark Smith, “The Mountain and the Flower: The Power and Potential of Nature in the World of Victorian Evangelism,” in God’s Bounty? The Churches and the Natural World, edited by Peter Clarke and Tony Claydon (Ecclesiastical History Society/Boydell Press, 2010), pp. 307–318. ↩