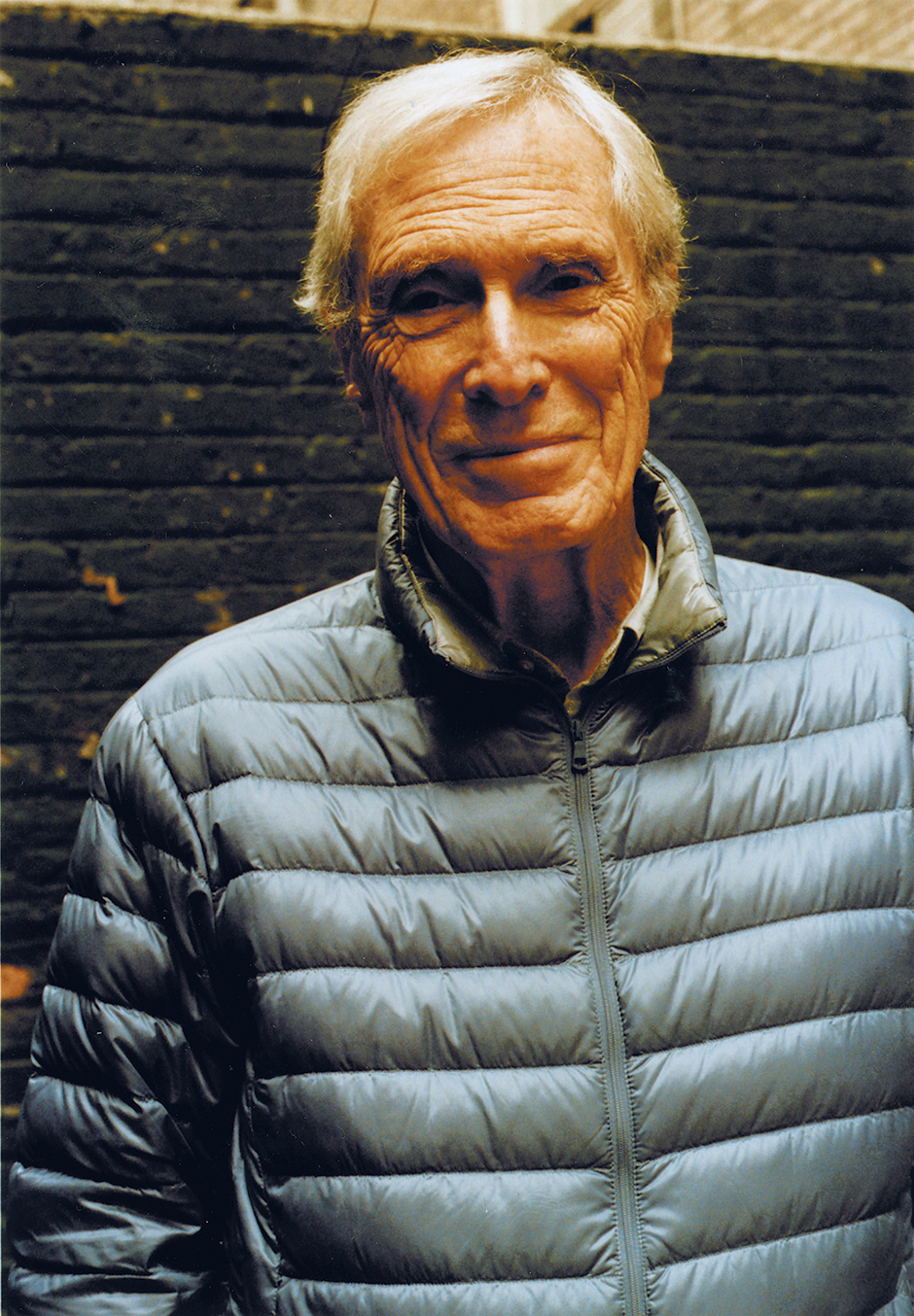

The poet Mark Strand, a contributor to these pages, died on November 29.

1.

JOSEPH BRODSKY

The following was given by Joseph Brodsky as an introduction to a reading by Mark Strand at the American Academy of Poets in New York City on November 4, 1986.

It’s a tall order to introduce Mark Strand because it requires estrangement from what I like very much, from something to which I owe many moments of almost physical happiness—or to its mental equivalent. I am talking about his poems—as well as about his prose, but poems first.

A man is, after all, what he loves. But one always feels cornered when asked to explain why one loves this or that person, and what for. In order to explain it—which inevitably amounts to explaining oneself—one has to try to love the object of one’s attention a little bit less. I don’t think I am capable of this feat of objectivity, nor am I willing even to try. In short, I feel biased about Mark Strand’s poems, and judging by the way his work progresses, I expect to stay biased to the end of my days.

My romance with Mr. Strand’s poems dates back to the end of the Sixties, or to the beginning of the Seventies, when an anthology of contemporary American poetry—a large paperback brick (edited by, I think, among others, Mark Strand) landed one day on my lap. That was in Russia. If my memory serves me right, Strand’s entry in that anthology contained one of the best poems written in the postwar era, his “The Way It Is,” with that terrific epigraph from Wallace Stevens that I can’t resist reproducing here:

The world is ugly,

and the people are sad.

What impressed me there and then was a peculiar unassertiveness in depicting fairly dismal, in this poem’s case, aspects of the human condition. I was also impressed by the almost effortless pace and grace of the poem’s utterances. It became apparent to me at once that I was dealing with a poet who doesn’t put his strength on display—quite the contrary, who displays a sort of flabby muscle, who puts you at ease rather than imposes himself on the reader.

This impression has stayed with me for some eighteen years, and even now I don’t see that much reason for modifying it. Technically speaking, Strand is a very gentle poet: he never twists your arm, never forces you into a poem. No, his opening lines usually invite you in, with a genial, slightly elegiac sweep of intonation, and for a while you feel almost at home on the surface of his opaque, gray, swelling lines, until you realize—and not suddenly, with a jolt, but rather gradually and out of your own idle curiosity, the way one sometimes looks out a skyscraper’s window or overboard of a rowboat—how many fathoms are there underneath, how far you are from any shore. What’s more, you’ll find that depth, as well as that impossibility of return, hypnotic.

But his strategies aside, Mark Strand is essentially a poet of infinities, not of affinities, of things’ cores and essences, not so much of their applications. Nobody can evoke absences, silences, emptinesses better than this poet, in whose lines you hear not regret but rather respect for those nonentities that surround and often engulf us. A usual Strand poem, to paraphrase Frost, starts in a recognition yet builds up to a reverie—a reverie toward infinity encountered in a gray light of the sky, in the curve of a distant wave, in a missed chance, in a moment of hesitation. I often thought that should Robert Musil write verse, he’d sound like Mark Strand, except that when Mark Strand writes prose, he sounds not at all like Musil but rather like a cross between Ovid and Borges.

But before we get to his prose, which I admire enormously and the reception of which in our papers I find nothing short of idiotic, I’d like to urge you to listen to Mark Strand very carefully, not because his poems are difficult, i.e., hermetic or obscure—they are not—but because they evolve with the immanent logic of a dream, which calls for a somewhat heightened degree of attention. Very often his stanzas resemble a sort of slow-motion film shot in a dream that selects reality more for its open-endedness than for mechanical cohesion. Very often they give a feeling that the author managed to smuggle a camera into his dream. A reader more reckless than I would talk about Strand’s surrealist techniques; I think about him as a realist, a detective, really, who follows himself to the source of his disquiet.

Advertisement

I also hope that he is going to read tonight some of his prose, or some of his prose poems. One winces at this definition, and rightly so. In Strand’s case, however, we encounter the real thing: as real as it was in the case of Zbigniew Herbert or of Max Jacob, though I doubt very much that either was Strand’s inspiration. For while those two Europeans were, very roughly putting it, carving their remarkable cameos of absurdity, Strand’s prose poems—or rather, prose-looking poems—unleash themselves with the maddening grandeur of purely lyrical eloquence. These pieces are great, crackpot, unbridled orations, monologues whose chief driving force is pure linguistic energy, mulling over clichés, bureaucratese, psychobabble, literary passages, scientific lingo—you name it—past absurdity, past common sense, on the way to the reader’s joy.

Had that writing been coming from the Continent, it would be all the rage on our island. As it is, it is coming from Salt Lake City, Utah, and while being grateful to the land of the Mormons for giving shelter to this writer, we should be in all honesty a bit ashamed for not being able to provide him with a place in our midst.

2.

CHARLES SIMIC

I met Mark Strand in 1968 at one of the several readings in New York City organized to launch the publication of Paul Carroll’s anthology called Young American Poets. Ours took place in Frank Stella’s studio in front of a small audience, which most likely had come to see where the famous artist worked rather than to hear two little-known poets. When James Wright, a greatly revered older poet, introduced us singing our praises and mentioning the titles of our poems, nobody but Strand and I seemed to notice that he had us confused. Not that we were hard to tell apart. Strand was tall and handsome and I was on the chubby side with sideburns a mile long. Of course, when we got up to read our poems we were both too embarrassed to correct him and failed to do so even at the dinner in a restaurant we were taken to afterward. I recall Strand making signs to me across the table daring me to do so, but nothing else remains in my memory, except that we became friends that night.

Strand was a man of exquisite taste already then. He had lived in Italy and Brazil and was not only familiar with European and South American poetry and literature but had an appreciation for fine cuisine, great wines, and elegant clothes, which was unheard of in literary circles in those days. Being in his company was both a joy and an education. Everything from how he furnished the various apartments and homes where he lived and the art he hung on their walls to the food he cooked and served his guests was an aesthetic experience. And so were his poems. He fussed over them, tinkering with them endlessly, as if striving to give the reader the same kind of pleasure.

Strand has been called both a surrealist and a poet writing in the tradition of Wallace Stevens and Elizabeth Bishop, and there’s some truth to that. He praised Edward Hopper for making the most familiar scenes in our lives appear remote and he sought in his poems to convey the same kind of estrangement for the reader. Our deepest experiences, Strand keeps reminding us, often turn out to be the most fleeting and seemingly inconsequential ones, and yet this is precisely where their beauty and poignancy lie:

Oh if you knew! If you knew! How it has been. How the ladies of the house would talk softly in the moonlight under the orange trees of the courtyard, impressing upon me the sweetness of their voices and something mysterious in the quietude of their lives. Oh the heaviness of that air, the perfume of jasmine, pale lights against the stones of the courtyards walls….

This melancholy, somber side in his poetry was relieved every now and then by an outburst of black humor. Like Samuel Beckett, Strand knew that the one who gropes all his life in an ambiguous universe is also a comic figure:

ELEVATOR

1.

The elevator went to the basement.The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if I was going up.

“I’m going down,” I said. “I won’t be going up.”

2.

The elevator went to the basement. The doors opened.

A man stepped in and asked if I was going up

“I’m going down,” I said. “I won’t be going up.”

Mark, dear old friend, I hope those teetotalers, the angels in heaven, had the sense to break their rule this once and serve you a magnificent Brunello upon your arrival.

Advertisement

This Issue

January 8, 2015

In Ferguson

A Better Way Out

Who Is Not Guilty of This Vice?