Great nineteenth-century critics taught us to imagine the Italian Renaissance as a world of nymphs walking gracefully on flowery meadows. They liked Piero di Cosimo, who painted his share of nymphs, but they did not have a great deal to say about him. Jacob Burckhardt praised the “extraordinarily solid composition and characters” of Piero’s Immaculate Conception with Saints in the Uffizi and the “completely charming details” of his Liberation of Andromeda. There he stopped. Walter Pater bracketed Piero in passing with his own favorite among the Florentine artists, Botticelli. But he took the comparison no further. Relatively few of the great nineteenth-century collectors sought Piero’s works. They wound up scattered, some of them in small museums. Apart from one important exhibition in New York in 1938, it has not been possible to see many of them at once.

But new generations of art historians began to ask new questions. Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl were fascinated by the metamorphoses that classical mythology underwent in the Middle Ages, as form and content pulled apart. Artists, they argued, portrayed gods and goddesses as medieval rulers, and medieval warriors as classical heroes. In the Renaissance, by contrast, form and content merged again, as accurate philology gave the ancient stories a spectacular new form. Panofsky reexamined the panels in which Piero conjured up the ancient myths. The Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, had a gorgeous painting, well populated with nymphs, which had traditionally been identified as the story of Hylas, the lover of Hercules. Putting all his immense learning into play, Panofsky showed that it represented the expulsion of Hephaestus from Olympus—and that Piero’s version of the myth incorporated minute details from ancient texts.

Panofsky also examined Piero’s scenes of primitive hunters and artisans at work. He showed that these too had a philological core, since they were inspired by the accounts of early human society in ancient Latin texts. Not all of Panofsky’s interpretations—especially his effort to show that several of these paintings formed a distinct series—have won general support. But he revealed the range of Piero’s artistic interests and techniques and the deep and questing power of his mind. All of these qualities are on view in the National Gallery’s wonderful exhibition, which covers the artist’s entire career.

Like Botticelli, Piero worked in many different fields of art. He produced some of the most handsome and dignified religious paintings of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries: altarpieces for churches and other religious institutions, as well as tondi, large circular paintings of members of the Holy Family, and paintings of individual saints, for private houses. But he also painted spalliere—wooden panels meant to serve as the backs of settles or other pieces of furniture, to be attached to the chests known as cassoni, or to form part of the paneling of a room. Piero used these, as well as some larger panels, for secular and mythological subjects. He crafted startlingly vivid portraits of individuals and strangely evocative images of religious objects.

The seven rooms devoted to Piero di Cosimo in Washington open up a world of ravishing visual interest. The paintings, hung on colored walls with the National Gallery’s special precision and flare, display scenes that seem at first to contrast wildly with one another. Piero’s works of sacred art, whether aimed at public display or composed as a background for private prayer and meditation, are stately. The Virgin Mary dominates, whether she is greeting the aged Elizabeth (soon to bear John the Baptist) or looking after her son. In either case, her decorum and gravity impress: she looks like one of those demure young Florentine women whom Alessandra Macinghi degli Strozzi would inspect in church while looking for a wife for her own son. The saints who appear with Mary share her gravity.

The longer one inspects these marvelous paintings, though—and the more one surveys their background detail—the more surprises they offer. Why does a bird fly distractingly past the leftmost arch in Piero’s monumental Madonna and Child with Saints Onuphrius and Augustine? Why must two baby angels and one sculpted head with wings help to keep the baldachin of the Virgin’s throne upright in another painting, while martyred saints press forward gently for their dual mystic marriage with the infant Jesus? Why give the angel who plays a three-stringed rebec for another infant Jesus a face joyous to the point of goofiness? In most cases, the gravity of the holy figures in the foreground is accentuated by the lively detail of street scenes and façades behind them. But sometimes—as with the massacre of the Holy Innocents by Herod that unfolds in turmoil far behind the Virgin and Elizabeth—the relation between foreground and background seems simply puzzling.

Advertisement

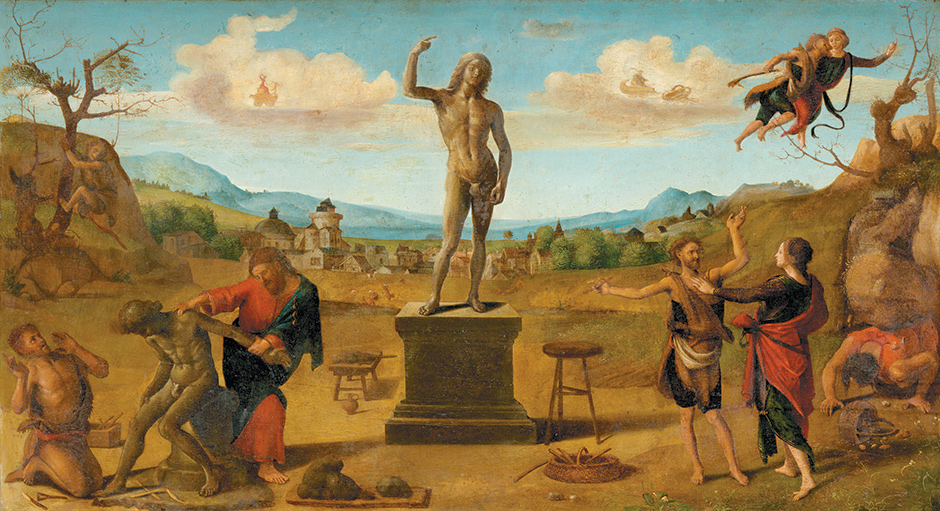

The mythologies—both the two great panels of Vulcan, fallen on the island of Lemnos and working with Aeolus, the god of the winds, at his forge, and the smaller panels that narrate the myths of Bacchus, Perseus, and Prometheus—are cast in a very different key. Here everything is motion, action, energy. The Bacchic procession to find honey ends in wild comedy as Bacchus’s sidekick Silenus is stung by bees; the Perseus and Prometheus panels, like magnificently anachronistic graphic novels, cram two or three incidents from ancient sources into every single image.

Nothing could seem less like the celestial world of the Virgin than the flowery island of Lemnos. Here, as Panofsky showed, Vulcan, lamed by his fall, tries to stand up after being thrown from Olympus for defending his mother against Jupiter. He finds himself in the midst of six nymphs gathering flowers, in the best fashion of Botticelli’s young women. Panofsky wrote that the nymphs “show no amorous excitement whatsoever.” He was partly right. Two converse; one, a study in the Ghirlandaiesque, guards her flowers as she turns her cool, perfect profile toward the boy. But another nymph appears above her, at the right edge of the painting. She drops her bouquet and looks ready to grab the handsome boy. Her broad grin shows that she would know how to have a good time with him. This disorderly figure seems provocatively close to her more decorous companion, as if Piero were challenging Florentine convention and Botticelli, its great master. It’s a sexy as well as a weirdly gorgeous image.

Fitting these wonderfully disparate works together isn’t easy, especially since much of Piero’s work was probably dispersed almost as soon as it was made. Tradition holds that he won his fame in large part as a creator of temporary arts. If the Paris of the late nineteenth century was a city of banquets, the Florence of the later fifteenth century was a city of processions. Some accompanied religious feasts—like the parade of the Company of the Magi that commemorated the Epiphany on January 6, as the Medici and their close friends, wearing fancy dress, celebrated the birth of the Savior and the beginning of Carnival.

Others were private—like the procession of two hundred pages, accompanying an ever-burning heart, that a Florentine patrician sent to declare his love to a young woman. Every one of them needed floats and costumes. Piero specialized in these. According to his sixteenth-century biographer Giorgio Vasari:

It was certainly a very beautiful thing to see, by night, twenty-five or thirty pairs of horses, most richly caparisoned, with their riders in costume, according to the subject of the invention, and six or eight grooms to each rider, with torches in their hands, and all clothed in one and the same livery, sometimes more than four hundred in number; and then the chariot, or triumphal car, covered with ornaments, trophies, and most bizarre things of fancy; altogether, a thing which makes men’s intellects more subtle, and gives great pleasure and satisfaction to the people.

Vasari showed special enthusiasm for the Car of Death that Piero constructed in conditions of special secrecy:

An enormous car drawn by buffaloes, black all over and painted with skeletons and white crosses; and upon the highest point of the car stood a colossal figure of Death, scythe in hand, and right round the car were a number of covered tombs; and at all the places where the procession halted for the chanting of dirges, these tombs opened, and from them issued figures draped in black cloth, upon which were painted all the bones of a skeleton, over their arms, breasts, flanks, and legs.

The spectacle “filled the whole city with fear and marvel together.” Old men, including some of Piero’s assistants, still remembered this spectacle in Vasari’s time, long after Piero’s death. Some read a political meaning into it. They argued that Piero had meant to predict that the Medici would soon return to Florence (as they did in 1512).

How far to trust Vasari is not clear. The documentation for Piero’s life is scanty. Vasari—as we will see—followed his own agenda in describing the artist. And the Washington exhibition daringly makes one point—one that curators rarely emphasize—brilliantly clear. When we look at and try to assess Piero’s work, we confront fragile painted surfaces that have changed form and color and been subjected to restoration over time. A massive altarpiece from the Yale Museum, still undergoing repair, gives in its damaged contours and faded colors a sense of the metamorphoses that paintings may experience in the restorer’s workshop—and makes us uncertain and hesitant about what they might originally have looked like, always a good thing. In many of Piero’s paintings, the Virgin wears garments of a relatively pale blue, less rich in texture and color than those of the saints and donors who flank her. Is this effect deliberate? Or did Piero use a blue pigment cheaper than ultramarine, which faded? Questions like these—as well as questions about the meaning and purpose of some of the most vibrant and memorable images—haunt the show.

Advertisement

Piero knew and drew on the work of other Florentine artists. Selections and flourishes from their work reappear in his—for example, the splendid clutch of riders, inspired by Paolo Uccello, whose horses’ hooves raise a cloud of dust on one side of his panel painting The Building of a Palace. But like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and other of his colleagues, Piero always kept an especially sharp eye on what the Flemings were doing. Like them, he must have been surprised, delighted, and inspired in 1483 when the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes was transferred, with considerable public ceremony, from Bruges to Florence, where it remains.

Piero learned an enormous amount from northern painters like van der Goes. They showed him how individual features reveal character in portraits. They taught him how to build up the magnificently textured, almost tactile cloaks and borders worn by so many of the saints in his sacred paintings—and the fantastic hilly landscapes inhabited by so many of his holy figures. They probably inspired the details, rendered with hypnotic exactitude, that appear in so many of his paintings, where they serve no clear dramatic purpose but delight the slow, careful examiner. Vasari singles out his

Visitation of Our Lady, with S. Nicholas, and a S. Anthony who is reading with a pair of spectacles on his nose, a very spirited figure. Here he counterfeited a book bound in parchment, somewhat old, which seems to be real, and also some balls that he gave to the S. Nicholas, shining and casting gleams of light and reflections from one to another.

Surely Piero also found inspiration in Flemish painting for the strange animals and monstrous beings that people so many of his works. As Panofsky remarked, Piero’s passion for depicting plants and animals “and his delicate sense of luminary and atmospheric values, lend a definitely Northern flavour to his pictures.”

But Piero was far too original simply to borrow and learn from others. He gave himself the same tests, again and again, though he did not always pass them: for example, depicting feet, which he did in an elegantly detailed manner, down to their splayed toes, and depicting hands, which he did rather awkwardly. Piero painted a great many babies, especially images of the baby Jesus. Some of them he modeled on Roman sculpture, but he also showed a real gift for bringing out the soft flesh and staccato movements of human infants. He loved setting himself exercises in foreshortening—such as the prone bodies and statues that appear in his wild hunting scene and in his Building of a Palace. Often—as in the horse and rider coming directly at the onlooker in the Palace panel—Piero pulled off this effect with bravura. At times, though, his foreshortened figures look awkward, and seem inconsistent with other aspects of the same painting’s spatial order.

Piero’s work raises questions of many kinds. How much, one wonders, did he actually know of the ancient myths and other materials that formed some of his favorite subjects? We do not even know for certain if he was literate. Yet we do know that he paid close attention—some of the time—to tiny details in the ancient writers who were his ultimate sources. Consider the panel painting of Perseus saving Andromeda from a sea monster, which he created for the bedroom of Filippo Strozzi’s enormous Florentine palace. It’s a dazzling image, as Vasari made clear. He praised everything from the charmingly intricate and implausible hills of the setting (“the landscape is very beautiful, and the coloring sweet and full of grace”) to the handsome and equally implausible creature that Perseus has to kill (“it is not possible to find a more bizarre or more fantastic sea-monster”). The picture swarms with curious detail.

The basic account of the myth came to Piero—as it did to everyone in his time—from the Metamorphoses of Ovid. And his painting incorporated any number of points from the original text. Ovid tells us that Andromeda looked to Perseus like a marble statue. Piero’s Andromeda, bound to a tree for the monster and nude from the waist up, is pale enough to be a sculptor’s work. Ovid describes Perseus’s sword as curved: Piero’s Perseus hacks away with a scimitar. Piero was selective: he found no place in his dramatic account of Perseus’s conquest of the monster for the comic Ovidian moment when the flying hero, stunned by Andromeda’s beauty, almost forgets to flap his wings. And he adapted creatively. In Ovid’s poem, Andromeda’s hair, moved by the wind, shows Perseus that she is still alive. In Piero’s painting, it’s Perseus’s mantle that is animated by the wind of his passage—and the sea, churned into motion by the monster.

How did Piero gain access to these textual details—or indeed to the more obscure notion that Vulcan, when he fell to the island of Lemnos, was greeted by nymphs? As Panofsky explained, they are not a feature of any celebrated ancient retelling of the myth. Following Greek sources, the late antique grammarian Servius remarked in his commentary on Virgil that the “Sintii” raised Vulcan on Lemnos. Medieval scribes, not recognizing the “Sintii,” turned them into nymphs (and, in another version, apes). As the joke goes, an economist cast up on a desert island with a heap of canned goods assumes a can opener. An art historian cast up in a museum with the classicizing work of an erudite artist may assume a humanist adviser—a learned man who either laid out a program for the artist—as Leonardo Bruni did, for example, for Ghiberti’s second set of bronze doors for the Florentine Baptistery—or at least provided him with a summary and useful details of what the ancients had written. But this figure, if he existed, remains elusive.

So do the exact sources that Piero drew on, as Dennis Geronimus makes clear in his discussion of Piero’s “primitive strain.” For he always used the classics, as he used Ovid, for his own distinctive ends. Two of the most striking of Piero’s panels, now in the Metropolitan Museum, depict what must be the earliest stage of human civilization. In one of them, humans, satyrs, and centaurs cooperate to hunt down and kill animals that a fire has flushed from their hiding places in the forest. In the other, similarly varied hunters join human women on a shoreline from which the fire is still visible. The presence of crude ships—and the fact that two women, clad in skins, cooperate in nursing a pup of some sort—reveal that at least some of these creatures (it’s not clear which) have developed emotional lives and created some technical devices.

The story Piero tells here comes from two Roman writers—the Epicurean poet Lucretius, who described the discovery of fire and its uses at the start of human history and emphasized the uniqueness of man’s ability to hunt, and the architectural writer Vitruvius, who also highlighted the vital role of fire in creating civilization—and the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who told a similar tale, making lightning the cause of the fire. The discovery of fire led in their accounts to the development of everything else, from clothing to language. Culture itself was contingent, the result of conflagrations set by chance.

In weaving his vision of early human history from these threads, as Panofsky pointed out, Piero offered a vision radically different from the biblical one. Giovanni Boccaccio, who summarized Vitruvius’s story of fire in his handbook Genealogy of the Pagan Gods, felt compelled to note that “that very talented man had not read the Pentateuch. Near the beginning of that he would have read of a very different creator of language, Adam, who named everything.” What did Piero think he was saying when he portrayed the origins of humanity—and even, apparently, its development from a much more polymorphous set of beings—in these starkly anti-Christian terms? He did not explain. Painters, after all, find it harder than writers to include the sort of saving parenthetical remark that enabled Boccaccio to ’scape whipping.

It’s not an easy question. Piero, as Geronimus shows, did not draw on any single one of the relevant Roman writers in detail as he laid out his vision of early human life. He followed Florentine custom—and Alberti’s advice—rather than an ancient example or story when he added to the festive procession that celebrates Perseus’s wedding with Andromeda a bearded figure who looks out and catches the eye of anyone looking at the image: very likely a self-portrait. But Piero probably did learn from Lucretius to emphasize the importance of hunting. And that is revealing. The texts that tell the story of fire and civilization were all known in Florence. The Florentine humanists Poggio Bracciolini and Niccolò Niccoli brought Lucretius back into circulation. Alberti studied both Lucretius and Vitruvius. And Poggio himself made a Latin adaptation of the relevant parts of Diodorus.

Yet not everyone who owned these books read them—much less drew the rich messages from them that Piero did. Ada Palmer, a historian at the University of Chicago, has recently published Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance, a detailed, lucid study of the ways in which fifteenth-century Italians read the newly discovered poem of Lucretius.1 Relatively few of them, she shows, took an interest in his radical history of civilization—as opposed to his excellent trove of new Latin vocabulary words. Piero, or his informant, was reading in much the same focused, insightful way as the erudite Florentine chancellor Marcello Adriani did in his own time—and perhaps comparing the earliest times, as Lucretius described them, to the new lands to the east and west, as travelers were beginning to describe these. The question of informants—and the nature of possible conversations between painters and scholars—becomes painful here. We simply don’t know where Piero’s literary materials came from, or in what form he gained access to them.

It may be still possible to shed some light on the painter’s mind. Vasari treated Piero as a sort of minor-league Leonardo da Vinci: eccentric, misanthropic, and inventive. Where Leonardo found inspiration in spots on the wall, Piero

would sometimes stop to gaze at a wall against which sick people had been for a long time discharging their spittle, and from this he would picture to himself battles of horsemen, and the most fantastic cities and widest landscapes that were ever seen; and he did the same with the clouds in the sky.

Given to long, solitary works and caprices, Piero, according to Vasari and others, would not allow the trees on his property to be trimmed, and he boiled fifty eggs at a time so he could save time on cooking and eating. He ended up isolated, impoverished, and abandoned, tormented by illness and unable to paint.

But recent scholarship has taught us to distrust this account—to see it as a kind of back-formation, created by Vasari for polemical purposes. We are left with the pictures. And when we bring together—as Panofsky did, perhaps a bit too systematically—Piero’s histories and mythologies, something like a set of ideas emerges from them: a set of ideas that are not entirely consistent, but that do seem to illuminate some of his other work. Consider some of Piero’s subjects: the terrifying early history of humanity, in which men who resemble Vico’s giants and Pliny’s monstrous races hunt and kill and, evidently, come together as friends; the story of Vulcan, god of the forge, who is thrown from Olympus, cherished by nymphs, and—in another magnificent, large-scale painting—teaches men to make tools and build houses; the story of Prometheus, who steals knowledge for man from the gods and pays a terrible price for doing so; a Renaissance palace, seen straight on and apparently complete, but surrounded by artisans and apprentices who are performing, rather than practicing, the arts and crafts needed to create such a masterpiece.

It all looks like a single, episodic work, crafted in multiple scales and over a long time: a celebratory pictorial history of human culture, which starts in fire and killing—but eventually proves able to rival nature itself, bringing forth great new things, even though these may come at a terrible price.

As early as the 1430s Alberti learned from Lucretius to fear that the world might be getting old. But the artists whose work he saw for the first time when he came to Florence in the same years taught him that his fears were unjustified. Like Lucretius himself, he realized from the artistry of his contemporaries that he was living in an explosion of creative energy:

I believed, as many said, that Nature, the mistress of things, had grown old and tired. She no longer produced either geniuses or giants which in her more youthful and more glorious days she had produced so marvelously and abundantly.

Since then, I have been brought back here [to Florence]—from the long exile in which we Alberti have grown old—into this our city, adorned above all others. I have come to understand that in many men, but especially in you, Filippo, and in our close friend Donato the sculptor and in others like Nencio, Luca and Massaccio, there is a genius for [accomplishing] every praiseworthy thing. For this they should not be slighted in favour of anyone famous in antiquity in these arts. Therefore, I believe the power of acquiring wide fame in any art or science lies in our industry and diligence more than in the times or in the gifts of nature.

Could Piero have been inspired, as Alberti was, by the extraordinary beauty of Florentine art and the extraordinary ingenuity of Florentine technology to devise his own visual history of human creativity?2

It seems possible. After all, one of the most stunning paintings in the National Gallery exhibition is Piero’s early double portrait of the architect Giuliano da Sangallo and his father, the musician Francesco Giamberti. A powerful, sharply etched study in character—the sunken mouth and craggy profile of Giamberti may have come from a death mask—the portrait innovates in one precise way. Both men appear with the implements of their arts, Giuliano with a compass and Francesco with a sheet of music. This is the earliest Renaissance portrait to identify its subjects’ callings. It’s reasonable to imagine that the proud young artist who produced this marvelous celebration of two artists, father and son, might have spent much of his life developing the thoughts that they only suggest: that men make their own arts, if not their own fates.

Much remains hard to set into context or explain. Piero’s strangely ceremonious image of a famous wooden crucifix in Lucca, for example, still calls out for explication. What role did such a painting play in a complicated fifteenth-century devotional life dominated by relics and images? So does his striking group portrait of the theologians who debated the doctrine of the Virgin Birth. The great nineteenth-century scholars gazed at Piero and found him hard to unravel. Their successors in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have given us a Piero we can appreciate as a master, in two senses: a master painter and a master thinker, whose ideas expressed themselves in strange and unforgettable images. The religious master, strangest in some ways of all the Pieros, awaits explication still.

-

1

Ada Palmer, Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance (Harvard University Press, 2014); for Piero’s reading and its context see also Alison Brown, The Return of Lucretius to Renaissance Florence (Harvard University Press, 2010), and Gerard Passannante, The Lucretian Renaissance: Philology and the Afterlife of Tradition (University of Chicago Press, 2011). ↩

-

2

For Piero’s views on architecture and technology, see the classic essay of Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt, “The Relation of Sculpture and Architecture in the Renaissance,” in The Renaissance from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo: The Representation of Architecture, edited by Henry Millon and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani (Rizzoli, 1994). ↩