Introduction

On October 8, the Nobel Committee announced that the 2015 Nobel Prize for Literature was being awarded to Svetlana Alexievich, a writer and journalist whose body of work is unique both in scope and in genre.

The bare facts of Alexievich’s biography reflect the nature of her greater subject: the memory, aspirations, tragedy, and fluid historical identity of Homo sovieticus. She was born in Ivano-Frankivsk, a city in western Ukraine that lies at the eastern edge of the Carpathian Mountains, about 85 miles south of Lviv, and a mere 150 or so miles from the borders of Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia, respectively. The city was annexed by the USSR only a few years before her birth in 1948. Her mother was Ukrainian and her father Belarussian. She grew up in Minsk, Belarus, where she studied journalism, developed her own exceptional voice, and became a Russian writer.

Over the course of several decades and numerous books, Alexievich has pursued a distinctive kind of narrative based on journalistic research and the distillation of thousands of firsthand interviews with people directly affected by all the major events of the Soviet and post-Soviet period. She has uncovered the unknown but crucial work that Soviet women did in World War II, recounted the memories of children caught up in the “Great Patriotic War,” documented the realities facing soldiers in the Soviet-Afghan war, which were kept from the Soviet public, and recorded the experiences of those who lived through the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

In her most recent book, she deftly orchestrates a great chorus of diverse voices to chronicle the human toll—emotional, physical, economic, and political—of the collapse of the USSR, a country that once made up a sixth of the world’s land mass.1 Alexievich’s oeuvre comprises nothing less than a history of epic proportions, which she has called “Voices of Utopia.” This undertaking has brought the writer many awards and accolades from Western European countries in particular, and from Russia, where her books have been printed and reprinted many times; she is a well-known critic of the Putin regime. In her home, Belarus, however, under the dictatorship of Aleksandr Lukashenko, she has been subject to the same political censorship and pressure as many of her colleagues (as Timothy Snyder pointed out in the NYR Daily

2). For over a decade she lived in various European cities, because it was not safe to return to Minsk (though she did in 2011), and her books have not been published in Belarus since 1994.

In announcing the award, the Swedish Academy called Alexievich’s “polyphonic writings…a monument to suffering and courage in our time.” “By means of her extraordinary method—a carefully composed collage of human voices,” the Academy went on to say, “Alexievich deepens our comprehension of an entire era.” As she writes:

I don’t just record a dry history of events and facts, I’m writing a history of human feelings. What people thought, understood and remembered during the event. What they believed in or mistrusted, what illusions, hopes and fears they experienced. This is impossible to imagine or invent, at any rate in such multitude of real details. We quickly forget what we were like ten or twenty or fifty years ago….

I’m searching life for observations, nuances, details. Because my interest in life is not the event as such, not war as such, not Chernobyl as such, not suicide as such. What I am interested in is what happens to the human being….

Svetlana Alexievich’s interest in what happens to the human being is evident on every page of her writing. Among other things, her work testifies to the immense power of compassion to create understanding of our fellow human beings.

The text below is from a collection of more than a dozen tales of suicide that Alexievich published in Russia in 1994 under the title Zacharovannye smert’iu (Enchanted by Death). In the introduction she wrote that she sought to “distinguish…the lonely human voice. They all sound different. Each one has its own secret.”

—Jamey Gambrell

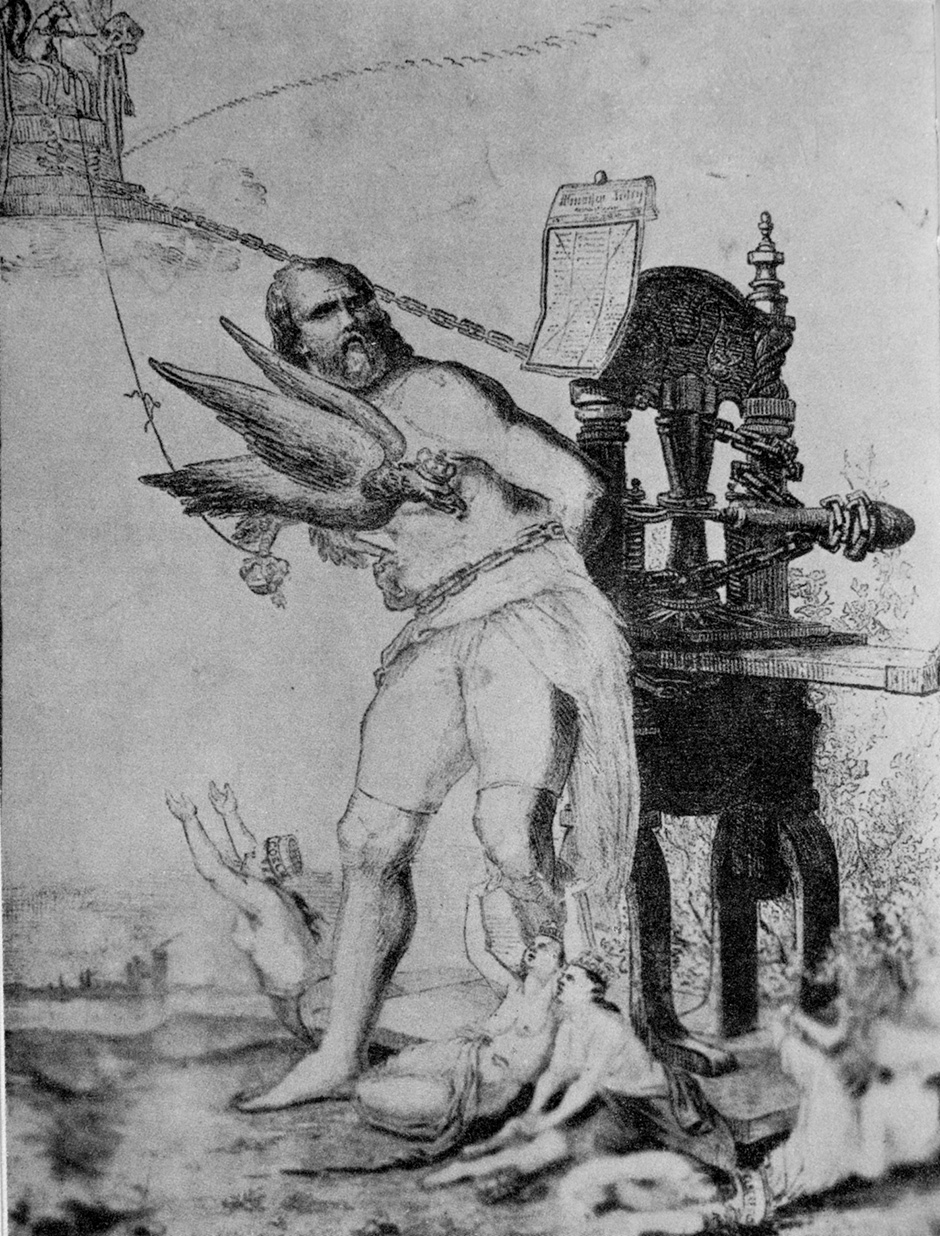

The Story of the Man Who Flew Like a Bird:

Ivan Mashovets—Graduate Student of the Philosophy Department

From the account of his friend, Vladimir Staniukevich, graduate student in the Philosophy Department:

…He wanted to leave unnoticed, of course. It was evening. Twilight. But several students in the nearby dormitory saw him jump. He opened his window wide, stood up on the sill, and looked down for a long time. Then he turned around, pushed hard, and flew… He flew from the twelfth floor…

A woman was passing by with a little boy. The youngster looked up:

“Mama, look, that man is flying like a bird…”

He flew for five seconds…

The district police officer told me all this when I returned to the dormitory; I was the only person who could be called his friend in any sense. The next day I saw a photo in the evening paper: he lay on the pavement face down…in the pose of a flying man…

Advertisement

I can try to put some of it into words… Although everything is slipping away… You and I won’t make it out of this labyrinth… It will be a partial explanation, a physical explanation, not a spiritual one. For instance, there’s something called the trust hotline. A person calls and says: “I want to commit suicide.” In fifteen minutes they dissuade him. They find out the reason. But it isn’t really the reason, it’s the trigger…

The day before he saw me in the hall:

“Be sure to come by. We have to talk.”

That evening I knocked on his door several times, but he didn’t open it. Through the wall I could hear he was there (our rooms are adjacent). He was pacing. Back and forth. Back and forth. “Well,” I thought, “I’ll drop by tomorrow.” Tomorrow I talked to the policeman.

“What’s this?” The policeman showed me a vaguely familiar folder.

I leaned over the table:

“It’s his dissertation. There’s the title page: Marxism and Religion.”

All the pages were crossed out. Diagonally, in red pencil, he’d written furiously: “Nonsense!! Gibberish!! Lies!!” It was his handwriting… I recognized it…

He was always afraid of water… I remember that from our college days. But he’d never said that he was afraid of heights…

His dissertation didn’t pan out. Well, to hell with it! You have to admit you’re a prisoner of utopia… Why jump from the twelfth floor on account of that? These days how many people are rewriting their master’s essay, their doctoral dissertation, and how many are afraid to admit what the title was? It’s embarrassing, uncomfortable… Maybe he decided: I’ll throw off these clothes and this physical shell…

Behavioral logic didn’t lead to this, but the act was committed nonetheless… There’s the concept of fate. You’ve been given a path to follow… You rise to it… You either rise, or fall… I think he believed that there is another life… In a thin layer… Was he religious? This is where speculation begins… If he believed, it was without intermediaries, without cultish organizations, without any ritual. But suicide is impossible for a religious person, he wouldn’t dare violate God’s plan… Break the thread… The trigger mechanism works more easily for atheists. They don’t believe in another life, aren’t afraid of what might be. What’s the difference between seventy years or a hundred? It’s just a moment, a grain of sand. A molecule of time…

He and I once talked about socialism not resolving the problem of death, or at least of old age. It just skirts it…

I saw him make the acquaintance of a crazy guy in a used bookstore. This guy, too, was rummaging around in old books on Marxism, like we were. Then he told me:

“You know what he said? ‘I’m the one who’s normal—but you’re suffering.’ And you know, he was right.”

I think that he was a sincere Marxist and saw Marxism as a humanitarian idea, where “we” means much more than “I.” Like some kind of unified planetary civilization in the future… When you’d drop by his room he’d be lying there, surrounded by books: Plekhanov, Marx, biographies of Hitler, Stalin, Hans Christian Andersen stories, Bunin, the Bible, the Koran. He was reading it all at once. I remember some fragments of his thoughts, but only fragments. I reconstructed them afterward… I’m trying to find meaning in his death… Not an excuse, not a reason… Meaning! In his words…

“What is the difference between a scholar and a priest? The priest comes to know the unknown through faith. But the scholar tries to comprehend it through facts, through knowledge. Knowledge is rational. But let’s take death, for instance. Just death. Death goes beyond thought.

“We Marxists have taken on the role of church ministers. We say we know the answer to the question: How do you make everyone happy? How?! My favorite childhood book was The Human-Amphibian by A. Belyaev. I reread it again recently. It’s a response to all the utopians of the world… The father turns his son into a human-amphibian. He wants to give him the oceans of the world, to make him happy by changing his human nature. He’s a brilliant engineer… The father believes that he’s uncovered the secret… That he’s God! He made his son into the most miserable of people… Nature doesn’t reveal itself to human reason… It only entices it.”

Advertisement

Here are a few more of his monologues. As I remember them, at least.

“The phenomenon of Hitler will trouble many minds for a long time to come. Excite them. How, after all, is the mechanism of mass psychosis launched? Mothers held their children up crying: ‘Here, Führer, take them!’

“We are consumers of Marxism. Who can say he knows Marxism? Knows Lenin, knows Marx? There’s early Marx… And Marx at the end of his life… The halftones, shades, the whole blossoming complexity of it all, is unknowable to us. No one can increase our knowledge. We are all interpreters…

“At the moment we’re stuck in the past like we used to be stuck in the future. I also thought I hated this my whole life, but it turns out that I loved it. Loved?… How can anyone possibly love this pool of blood? This cemetery? What filth, what nightmares…what blood is mixed into it all… But I do love it!

“I proposed a new dissertation topic to our professor: ‘Socialism as an Intellectual Mistake.’ His response was: ‘Nonsense.’ As if I could decipher the Bible or the Apocalypse with equal success. Well, nonsense is a form of creativity, too… The old man was bewildered. You know him yourself—he’s not one of those old farts, but everything that happened was a personal tragedy for him. I have to rewrite my dissertation, but how can he rewrite his life? Right now each of us has to rehabilitate himself. There’s a mental illness—multiple, or dissociated, personality disorder. People who have it forget their names, social positions, their friends and even their children, their lives. It’s a dissolution of personality…when a person can’t combine the official take or government belief, his own point of view, and his doubts…how true is what he thinks, and how true is what he says. The personality splits into two or three parts… There are plenty of history teachers and professors in psychiatric hospitals… The better they were at instilling something, the more they were corrupted… At the very least three generations…and a few others are infected… How mysteriously everything eludes definition… The temptation of utopia…

“Take Jack London… Remember his story about how you can live life even if you’re in a straitjacket? You just have to shrivel up, sink down, and get used to it… You’ll even be able to dream…”

Now that I analyze what he said…follow his train of thought… I can see that he was preparing for departure…

We were drinking tea one time, and out of the blue he said:

“I know how long I have…”

“Vanya, what on earth are you saying!” my wife exclaimed. “We were just getting ready to marry you off.”

“I was joking. You know, animals never commit suicide. They don’t violate the course…”

The day after that conversation the dormitory housekeeper found a suit, practically brand new, in the rubbish bin; his passport was in the pocket. She ran to his room. He was embarrassed and muttered something about having been drunk. But he never ever touched a drop! He kept the passport, but gave her the suit: “I don’t need it anymore.”

He’d decided to get rid of these clothes, this physical membrane. He had a more subtle, detailed understanding than we did of what awaited him. And he liked Christ’s age.

One might think he’d gone mad. But a few weeks earlier I’d heard his research presentation… Water-tight logic. A superb defense!

Does a person really need to know when his time will come? I once knew a guy who knew it. A friend of my father’s. When he left for the war, a gypsy woman prophesied: he needn’t be afraid of bullets because he wouldn’t die in the war, but at age fifty-eight at home, sitting in an armchair. He went through the whole war, came under fire, was known as a foolhardy fellow, and was sent on the most difficult missions. He returned without a scratch. Until age fifty-seven he drank and smoked since he knew he’d die at fifty-eight, so until then he could do anything. His last year was terrible… He was constantly afraid of death… He was waiting for it… And he died at age fifty-eight, at home…in an armchair in front of the television…

Is it better for a person when the line has been drawn? The border between here and there? This is where the questions begin…

Once I suggested he dig into his childhood memories and desires, what he’d dreamed of and then forgotten. He could fulfill them now… He never talked to me about his childhood. Then suddenly he opened up. From the age of three months he had lived in the country with his grandmother. When he got a bit older he would stand on a tree stump and wait for his mama. Mama returned after he’d finished school, with three brothers and sisters—each child from a different man. He studied at the university, kept ten rubles for himself, and sent the rest of his stipend home. To Mama…

“I don’t remember her ever washing anything for me, not even a handkerchief. But in the summer I’ll go back to the country: I’ll repaper the walls. And if she says a kind word to me, I’ll be so happy…”

He never had a girlfriend…

His brother came for him from the countryside. He was in the morgue… We began looking for a woman to help, to wash him, dress him. There are women who do that sort of thing. When she came she was drunk. I dressed him myself…

In the village I sat alone with him all night. Amid the old men and women. His brother didn’t hide the truth, although I’d asked him not to say anything, at least to their mother. But he got drunk and blabbed everything. It poured for two days. At the cemetery a tractor had to pull the car with the casket. The old ladies crossed themselves fearfully and zealously:

“Went against God’s will, he did.”

The priest wouldn’t let him be buried in the cemetery: he’d committed an unforgivable sin… But the director of the village council arrived in a van and gave his permission…

We returned at twilight. Wet. Destroyed. Drunk. It occurred to me that for some reason righteous men and dreamers always choose these kinds of places. This is the only kind of place they are born. Our conversations about Marxism as a unified planetary civilization floated up in my memory. About Christ being the first socialist. And about how the mystery of Marxist religion wasn’t fully comprehensible to us, even though we were up to our knees in blood.

Everyone sat down at the table. They poured me a glass of homemade vodka right away. I drank it…

A year later my wife and I went to the cemetery again…

“He’s not here,” my wife said. “When we came the other times we were visiting him, this time it’s just a tombstone. Remember how he used to smile in photographs?”

So he had moved on. Women are more delicate instruments than men, and she felt it.

The landscape was the same. Wet. Dilapidated. Drunk. His mother showered us with apples for the trip. The tipsy tractor driver drove us to the bus stop…

This Issue

November 19, 2015

A Conversation in Iowa—II

‘His Joy, His Life’