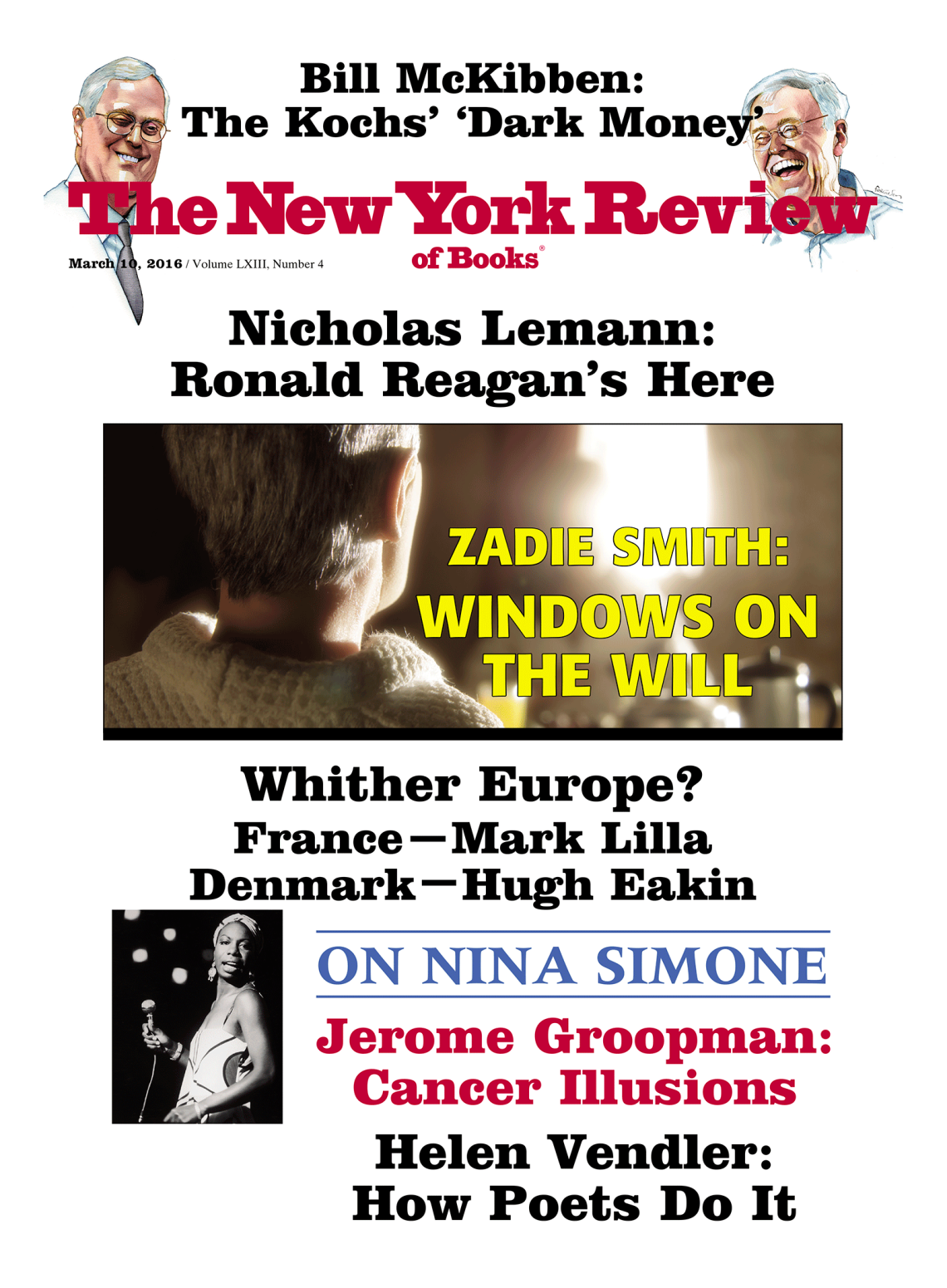

In 1968, an interviewer for New York public television asked the singer and pianist Nina Simone what freedom meant to her. “It’s just a feeling,” she replied, seemingly flustered by the question. Then, suddenly, an answer occurred to her. “I’ll tell you what freedom is to me: no fear. I mean really, no fear!”

This exchange appears early in Liz Garbus’s remarkable documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?, and it’s a startling moment, for if Simone, who died in 2003, conveyed anything on stage, it was fearlessness. Frustrated in her ambition to become a classical pianist, she smuggled Bach into the night club, combined his music with folk, blues, and jazz, and enforced recital hall rules: those who made any noise while she played could expect a cold stare or a tongue-lashing. Her repertoire was catholic—Gershwin, Ellington, Jacques Brel, Kurt Weill, Bob Dylan—but whatever she sang ended up sounding like a Nina Simone tune. She did not so much interpret songs as take possession of them.

Her most famous song, however, was one that she composed herself. “Mississippi Goddam” was written in 1963, the same year as Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” and provided a sharper expression of the mood among young civil rights activists. “This is a show tune, but the show hasn’t been written for it yet,” Simone coyly announces, before working herself into a furious assault on white counsels of patience:

Yes you lied to me all these years

You told me to wash and clean my ears

And talk real fine just like a lady

And you’d stop calling me Sister Sadie

Oh but this whole country is full of lies

You’re all gonna die and die like flies

I don’t trust you any more

You keep on saying, “Go slow!”

The mere fact that Simone dared to say “Mississippi goddam” represented a revolution in black political oratory. As Dick Gregory recalls in Garbus’s film, “We all wanted to say it, but she said it.”

Simone’s courage was undeniable, but it was also a shield, even a mask, designed to protect her from hostile forces, real and imagined. White supremacy was not the only hellhound on her trail. She suffered from bipolar disorder, a condition that remained undiagnosed until the 1980s, when her demons had all but taken over and a Dutch fan saved her from near vagrancy. She had a weakness for tough men and hustlers: “A love affair with fire,” as her daughter Lisa Simone told Garbus. (Lisa Simone is an executive producer of the documentary.)

Simone was also deeply tormented about her desires for women. “I have to live with Nina, and that is very difficult,” she confessed in an interview. Just how difficult is the story of Alan Light’s biography, What Happened, Miss Simone?, which was “inspired” by Garbus’s film and based on the same archive of source material, including Simone’s diaries and letters. Light’s prose is often hackneyed, but he provides an even more probing account of Simone’s inner struggles than Garbus. Far from detracting from her civil rights heroism, it makes that achievement all the more astonishing.

Simone was born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in 1933, in Tryon, North Carolina, the sixth of her parents’ eight children. Her father, John Divine, had lost his dry-cleaning business during the Depression, only to be idled altogether by intestinal obstruction. Her mother, Mary Kate, a traveling Methodist minister, supported the family as a maid. Mary Kate was an emotionally distant figure, but she recognized her daughter’s precocious musical talent, and by age six Eunice had become the regular church pianist in Tryon. At revival meetings she learned how to improvise, as well as how to put audiences into a trance.1

Performing on piano with the community choir in 1939, Eunice attracted a pair of white benefactors. One was her mother’s employer, Mrs. Miller, who offered to pay for classical piano lessons. The other was the woman who became her teacher, Muriel Mazzanovich, the British wife of a Russian painter. Every Saturday she crossed the railway tracks to study Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms with “Miz Mazzy,” a kindly woman who, with her white hair and pale skin, struck her as “an alien.” The town took immense pride in its young prodigy, and established a fund to pay for her education. Music, she discovered, was power, but it was also a terrible “burden.” To most whites in Tryon she was an oddity—Mrs. Mazzanovich’s “little coloured girl”—while no one in her family “knew how isolated my music made me.”2 Her mother barely showed her any affection, yet expected her to become America’s first black classical pianist. At her first recital, when she was ten, her parents moved from their seats to make way for a white family who wanted a better view of her fingers. Eunice refused to perform until her parents could return to their seats. Some whites in the audience giggled. After that, “nothing was easy any more,” as she wrote in her 1991 memoir I Put a Spell on You.

Advertisement

Nobody had warned her that she might not be welcome in the very white world of classical music: racism, according to Simone, was the “great unspoken” in her home. After graduating from boarding school, she took classes at Juilliard for a year and a half, while preparing for the entrance exams at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where her parents had moved to support her career. It never occurred to her that she might not be accepted. Curtis’s rejection was a shocking blow not only to her ego, but to her sense of reality: “You feel the shame, humiliation and anger at being just another victim of prejudice and at the same time there’s the nagging worry that maybe…you’re just no good.” When her piano teacher in Philadelphia, Vladimir Sokoloff, heard her play jazz, he encouraged her to pursue it, but she shrugged off the suggestion, saying, “My first love is classical music.”3

Rejection by her first love led her to create a highly distinctive style. It was born at the Midtown Bar in Atlantic City, where Eunice landed a gig in 1954. Terrified that her mother might find out she was playing the “devil’s music” in a nightclub, she took the stage name Nina Simone: “Nina” from “niña,” a term of endearment used by an ex-boyfriend; “Simone” from Simone Signoret. She played as much classical music as she could get away with, weaving Bachian counterpoint and Romantic chromaticism into popular tunes.4 But what began as an effort to nurse her wounds ended up providing “a pleasure…almost as deep as the pleasure I got from classical music.” Although she’d had no training as a singer, her husky contralto was unusually expressive, at once earthy and operatic, with an alluring tinge of androgyny.

Many of her first fans, according to Light, were gay. One of them was a waiter at the Midtown, Ted Axelrod, who introduced her to Billie Holiday’s version of “I Loves You, Porgy.” Her 1958 recording of that song for Bethlehem became her first hit. (She signed away her rights and only began to make money off her Bethlehem recordings in the 1990s, after filing a series of lawsuits.) Simone dropped the demeaning “s” from “loves,” and imbued the song with a plaintive majesty. Stanley Crouch told Liz Garbus that when he finally heard the original version of the song, he thought, “They need to throw that version away and go study her version.”5

In 1959, Simone moved to New York, leaving behind her husband Don Ross, a white beatnik. (The marriage soon folded.) She struck up close friendships with James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, LeRoi Jones, Miriam Makeba, and Lorraine Hansberry, who became her political mentor. Members of a black bohemian world that stretched from Harlem to the Village, they shared her interest in fusing modern art with black themes, and in African independence struggles; several among them were gay or bisexual.6 “She is strange,” Hughes wrote in his liner notes to one of her early recordings. “So are the plays of Brendan Behan, Jean Genet, LeRoi Jones, and Bertolt Brecht.”

It was a perceptive remark, linking Simone to the Grove Press avant-garde. At the Village Gate, a club that had just opened in the basement of an old hotel on Bleecker Street, Simone proved that she was much more than a “supper club songstress,” or even than a jazz singer. (As she often noted, there was “more folk and blues than jazz in my playing.” Stanley Crouch points out that Simone refused to “submit to the force of the band,” as more conventional jazz singers do, because “she liked it to be about her.”) Her classical training was never far from the surface. She coaxed a long, slow, almost perversely gloomy variation out of Cole Porter’s “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To,” making it sound like a Bach invention. By the time her voice enters, a low and distant moan rising over a flurry of sixteenth notes, Porter’s melody has been infused with an aching eroticism.

Eroticism and suffering lay at the heart of Simone’s work from the very start: she seemed to have one foot in the deep South and another in Weimar cabaret. Not surprisingly, she often found herself compared to Billie Holiday, but she dismissed Holiday as a “drug addict,” and preferred to be compared to Maria Callas. Still, she made an exception for “Strange Fruit,” the Lewis Allan song about lynching that Holiday had made her own, for the way it “tears at the guts of what white people have done to my people…. It really, really opens up the wound completely.”

Advertisement

Jazz critics were perplexed by Simone, whose voice lacked the range of Sarah Vaughan or the suppleness of Ella Fitzgerald. “I confess I have no idea what Miss Simone’s appeal is,” Martin Williams wrote. But audiences had no trouble discerning it. Simone cut deeper than her peers: she knew how to open the wound, to make pain audible and moving. So long as she felt adored, she was full of mischievous, salty banter in her mike breaks. But if she felt slighted, she could be explosive, even violent. Art D’Lugoff, the owner of the Village Gate, hired bodyguards to protect his customers.

In New York as in Atlantic City, Simone attracted a large gay following. (When Richard Pryor said “White people had Judy Garland, we had Nina,” he had little idea how much the two had in common, as queer icons.) She hung out at a lesbian bar called Trude Heller’s, and was romantically linked to a prostitute she had roomed with in Philadelphia. Her new boyfriend, Andrew Stroud, was so afraid that she had been “contaminated” by “gay associations” that he forced her to sever all her lesbian ties. A broad-shouldered, light-skinned Harlem detective sergeant, Stroud cut a fearsome profile. “He scared me to death,” Simone said. “It was like he just took over, and I’m glad of that.” At their engagement party at the Palladium Ballroom, a fan passed Simone a note. When they left the club, Stroud, who had been drinking white rum all evening, beat her up on the street. He then took her home in a cab, put a gun to her head, tied her to the bed, and raped her. They married soon after, in 1961, and nine months later she bore their only child, Lisa. Stroud quit the police force and became her manager.

As even Simone conceded long after their divorce, she did well by him, professionally. Under his management she enjoyed her greatest creative streak, recording a string of albums for Philips and RCA that earned her reputation as the “high priestess of soul.” He rented out Carnegie Hall for her, set her up in a thirteen-room house in Mount Vernon, and promised to make her a “rich black bitch.” But she resented him for making her work so hard and for failing to satisfy her sexually. She wrote in her diary of feeling “stuck between desire for both sexes,” and, as she confessed in a letter to Stroud, “I don’t think I’ll ever lose my fear of you.”

She was nearly as afraid of herself. “I’m looking at ‘3 Faces of Eve’—think it’s significant in a psychological study of myself,” she wrote in her diary. In another entry she described herself as “the kind of colored girl who looks like everything white people despise,” and wondered why she hadn’t killed herself. According to Stroud, “she was just unhappy to be black, and what she termed ugly.” Yet the voice she assumed in public was the exact opposite, an affirmation of négritude that transformed self-loathing into defiant pride.

The turning point in her transformation was the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. She was hardly a stranger to civil rights politics: she had performed at civil rights benefits and traveled to Lagos with Baldwin and Hughes; the racial echoes of songs like “Brown Baby” were no secret to her admirers in Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.7 But after the killing of four little girls in Birmingham, she headed to the garage and tried to make a home-made gun with her husband’s tools. “If I had had the choice,” she said, “I would have been a killer.”

At Stroud’s suggestion, she instead channeled her anger into music.8 The first fruit of what would be a harvest of protest songs was “Mississippi Goddam.” It appeared on her first album for Philips, In Concert, along with an apocalyptic version of “Pirate Jenny” from The Threepenny Opera, in which Jenny is reimagined as a black maid who inflicts Old Testament justice on her tormentors. In Concert was released in 1964, the same year as LeRoi Jones’s incendiary one-act play, Dutchman. Like Jones, who would soon embrace black nationalism and rename himself Amiri Baraka, Simone scorned interracial hand-holding. What she wanted, as she cried in her epic 1965 version of the spiritual “Sinnerman,” was “power!”

Like Baraka, Simone gave expression to a taboo emotion that, in a 1968 best-seller, two black American psychiatrists would define as “black rage.” Her songs were peopled with avenging black angels, most famously a woman named Peaches who, in her 1966 song “Four Women,” declares that she will “kill the first mother I see.” Seldom has anyone combined art and protest to such a sublime effect, in the classical sense of fusing beauty and terror. One of the reasons she loved the Black Panthers was that “they scare the hell out of white folks, too, and we certainly need that.” At the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival—where the Panthers, not the police, provided security—Simone asked her audience if they were “ready to smash white things” and, if necessary, to kill. Whether or not Simone was ready herself, she put on a brilliantly menacing performance.

By taking up the cause of civil rights in her music, Simone at last found, in her words, “a purpose more important than classical music’s pursuit of excellence.” It was so important that she was willing to play music that, as a classically trained pianist, she had considered beneath her. “I’m not a blues singer, I’m a diva,” she insisted. But on her deliciously raw 1967 album Nina Simone Sings the Blues, she proved that she could be both. She wore her Afro in a queenly dome and cultivated a funkier sound, surrounding herself with African percussion and congas in concert.

According to Angela Davis, whom Simone visited in prison in 1971 bearing a red helium balloon that became a permanent fixture in her cell, Simone “announced, asserted and innovatively played the changes of the movement.” She was movement royalty: a neighbor of Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X’s widow, and a confidante of Stokely Carmichael, who married her friend Miriam Makeba. But the consolations of the movement couldn’t provide Simone with a refuge from her anguish. She envied activists who could “go back into their communities to live out the ideas they believed in. They belonged; I didn’t…. I was lonely in the movement like I had been lonely everywhere else.”

Being a woman in a movement dominated by men exacerbated her loneliness. In her music, Simone would devote herself increasingly to the experience of black women, nowhere more powerfully than in “Four Women,” which announced the birth of a distinctively black feminist sensibility. (Oddly, the song is ignored in Garbus’s film.) It is a ballad, little more than a languid vamp for piano and bass, softly accented by percussion, over which Simone recounts the ordeals of four black women of different skin tones: a Toni Morrison novel compressed into four stanzas. The pace is so stately as to be almost morose, until its shattering climax, which Simone likened to a “razor cut.”

For all her defiance, Simone began to unravel by the early 1970s. She remained haunted by the death of Lorraine Hansberry, in 1965, and the other two relationships that helped preserve her fragile grip on reality—the civil rights movement and her marriage—were crumbling. Stroud left her after their threesome with a woman who claimed to be an Ethiopian princess: “I was an eyewitness to the sexual preference…. I should’ve walked out before.” Simone hired a pair of hit men to kill him; he wasn’t home when they arrived, and the plot was called off. It Is Finished was the title of her last record for RCA, released in 1974; there would be only a few more—barely listenable—studio recordings. She led a nomadic life that took her to Barbados, then Liberia, and then Europe. America, she decided, was a “cancer” and she wanted no part of it. (She also owed hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid taxes to the IRS.)

Simone’s remaining thirty years, largely in self-imposed exile—the story of “what happened” to Miss Simone—make for almost unbearable reading. She drifted in and out of mostly delusional relationships with unattainable men, including the prime minister of Barbados, and allowed herself to be swindled by others. She stripped naked on a dance floor in Liberia, an experience she celebrated in a song called “Liberian Calypso,” but according to her guitarist Al Schackman, “they couldn’t stand her in Africa.” She disowned her father when she overheard him telling her brother that he, not their mother, had supported the family, a lie that made her want to “kill him right there where he sat.” She became her daughter’s tormentor, calling her a “half-breed” because she’d inherited her father’s light complexion, and beating her so severely that she ran back into her father’s arms.

As her condition deteriorated, she began to imagine, as she wrote in her memoir, that “the whole world was ganging up on Nina Simone.” At a performance at the Village Gate in 1979, she broke into a hysterical rant against Jews; James Baldwin came to her rescue, sitting beside her at the piano and imploring her to sing.9 In the early 1980s she was put on Trifolon, a drug that impaired her motor skills, but she kept performing, and by the 1990s she was making $85,000 for a single concert and collecting royalties on her old hits. That allowed her to buy a house in the South of France and support a newly acquired cocaine habit. She hired a young gay man she’d met in a Los Angeles hospital to be her manager and bought him a Mercedes. He moved into a condo near her house and neglected her.

In her final interviews, Simone continued to speak of her extraordinary body of work as if it had all been a detour from the career she was denied in classical music. Two days before her death, the Curtis Institute of Music awarded her an honorary doctorate, correcting an error that proved to be among the school’s most important contributions to musical history. For if it had accepted Eunice Waymon, there may never have been a Nina Simone.

This Issue

March 10, 2016

Windows on the Will

Kicked Out in America!

-

1

“You ever been to revival meetings?” Simone asks her listeners in “Children Go Where I Send You,” from her 1961 live recording Nina at Village Gate. “I bet you don’t know what I’m talking about! Well, you in one right now!” ↩

-

2

Simone would later draw on these feelings of alienation in “Mississippi Goddam”: “I don’t belong here/I don’t belong there/I’ve even stopped believing in prayer.” ↩

-

3

As Light notes, there had been a few black students at Curtis, including a woman in the piano department. Sokoloff, who would have been her teacher at Curtis, said she was “not a genius, but she had great talent,” and insisted she was rejected because there were better applicants. Simone, however, never doubted that she was rejected because of her race. ↩

-

4

Her model at the time was probably Hazel Scott, a black pianist and singer who melded jazz cabaret and classical music. Simone never mentions Scott in her memoir, and neither does Light. But according to Nadine Cohodas in her well-researched if cranky biography, Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone (Pantheon, 2010), the young Eunice Waymon worshiped Scott, a woman of sultry beauty and worldly sophistication. That the walls of her dormitory at Allen High, a boarding school in Asheville, North Carolina, were covered with photographs of Scott also suggests a school-girl crush. At Allen she was far from Edney, her boyfriend in Tryon, whom she would forever describe as her one true love. But she does not seem to have lacked for company: Light reports that Simone had several same-sex affairs there. ↩

-

5

In Garbus’s film we see her perform “I Loves You, Porgy” at the Playboy Penthouse, seemingly the only black face in an all-white crowd, introduced by Hugh Hefner as a star who “came out of nowhere.” ↩

-

6

Atallah Shabazz, one of Malcolm X’s daughters, remarks in Garbus’s film that Simone was not “at odds with the times, the times were at odds with her.” This was particularly true of her sexuality, which chafed against the “respectability” politics of the mainstream civil rights movement, with its emphasis on bourgeois family values, and against Black Power, with its vision of heroic black masculinity. ↩

-

7

SNCC activists joked that the only time they forgot their nonviolent training was when someone stole their Simone records. ↩

-

8

When she met Dr. King, she walked right up to him and said, “I’m not non-violent.” “That’s OK, sister, you don’t have to be,” he replied. For all her misgivings about nonviolence, she wrote a deeply moving elegy for King, and premiered it at a musical festival three days after his assassination: “Why? The King of Love Is Dead.” ↩

-

9

Stanley Crouch, who reviewed the show in The Village Voice, worried that it would “feed the terrible backlash against black people that is again starting to form in this country.” ↩