“On one side of town I was an Uncle Tom,” said James Baldwin in an interview with The Paris Review, “and on the other the Angry Young Man.” But the list of epithets was much longer than that. Robert Kennedy, apoplectic at Baldwin’s statement in a private meeting in 1963 that black Americans couldn’t be counted on to fight in Vietnam, called him a “nut.” Harold Cruse, who attended the same meeting with Kennedy, complained of Baldwin’s “intellectual inconsistencies,” while Richard Wright, his earliest idol and first champion, considered him an ungrateful apostate. To Eldridge Cleaver, Baldwin was a traitor, with a “grueling, agonizing, total hatred of the blacks, particularly of himself, and the most shameful, fanatical, fawning, sycophantic love of the whites.” British Immigration named him a persona non grata and J. Edgar Hoover, who kept a case file on Baldwin at the FBI that ran 1,884 pages long, declared him “a well-known pervert” and a threat to national security.

Baldwin, for his part, accepted no characterization. “A real writer,” he wrote, “is always shifting and changing and searching.” The credo guided his work and his life. He moved to France at the age of twenty-four to avoid “becoming merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer.” Later he would recoil whenever someone described him as a spokesman for his race or for the civil rights movement. He rejected political labels, sexual labels (“homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual are twentieth-century terms which, for me, really have very little meaning”), and questioned the notion of racial identity, an “invention” of paranoid, infantile minds. “Color is not a human or a personal reality,” he wrote in The Fire Next Time. “It is a political reality.”

His refusal to align himself with any bloc within the civil rights movement isolated him, and he suffered from it—Cleaver’s attack wounded him, as did Wright’s sense of betrayal and Martin Luther King Jr.’s decision to exclude him from the list of speakers at the March on Washington. But the same resistance to alliances that cost him during his lifetime has given shape and power to his afterlife. Now that the old factions have disintegrated, and the national discussion of race has largely retreated from debates over proposed solutions to a debate over whether problems still exist, Baldwin’s work has regained its influence. That his observations about race in America feel as relevant and cutting as ever is as much a testament to his insight as to the level of the current discourse.

Today, like sixty years ago, much of the public rhetoric about race is devoted to explaining to an incurious white public, in rudimentary terms, the contours of institutional racism. It must be spelled out, as if for the first time, that police killings of unarmed black children, indifference to providing clean drinking water to a majority-black city, or efforts to curtail the voting rights of minority citizens are not freak incidents but outbreaks of a chronic national disease. Nebulous, bureaucratic terms like “white privilege” have been substituted for “white supremacy,” or “micro-aggressions” for “casual racism.” “All Power to the People,” “By Any Means Necessary,” and “We Shall Overcome” have yielded to the understated, matter-of-fact “Black Lives Matter.” The rhetorical front has withdrawn from “How can we cure this?” to “What is the nature of the problem?”

Writers, scholars, and activists have turned to Baldwin for answers. The first annual volume of The James Baldwin Review appeared last year1 and at least a dozen books have been published about Baldwin since Barack Obama’s inauguration, most of which comb the embers of his legacy for some new spark; these include monographs about Baldwin’s life in Turkey and in Provence, his views on the criminal justice system, and his writing on music. One of the more valuable recent entries is Douglas Field’s All Those Strangers, an idiosyncratic biography that focuses on three (somewhat) neglected fields of Baldwin study: his relationship to the political left and the FBI, his thinking about Africa, and his conflicting views on religion and spirituality. Field emphasizes the paradoxical nature of Baldwin’s various identities. The strangers of the title are Baldwin’s incarnations:

Baldwin the deviant rabble rouser…; Baldwin the civil rights activist…; Baldwin the passé novelist and homosexual sidelined by Black Nationalists; Baldwin the expatriate; and the Baldwin struggling to work out his conflicted relationship to Africa.

As Field examines in turn each of these strangers, he creates a portrait of a writer of “outright contradictions” who sought truth at the expense of ideological purity. Baldwin was often hailed as a prophet but this praise was misplaced: he could not predict the future, but few writers were able to diagnose the present as vividly or unsparingly. That was enough.

Advertisement

With the man himself having departed the scene three decades ago, contemporary writers have chased his ghost. In The New Yorker, Teju Cole traveled to Leukerbad, the town where Baldwin finished Go Tell It on the Mountain (and the subject of his essay “Stranger in the Village”); in The New York Times, Ellery Washington followed Baldwin’s trail around Paris; and, again in The New Yorker, Thomas Chatterton Williams trespassed onto the property in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where Baldwin spent the final seventeen years of his life. (“Today, among my generation of black writers and readers,” writes Williams, “James Baldwin is almost universally adored.”)

No one has done more to popularize Baldwin in recent years than Ta-Nehisi Coates, who used Baldwin’s address to his nephew in “My Dungeon Shook,” the first part of The Fire Next Time, as a model for Between the World and Me, the most widely read book on race in America in a generation.2 Consecutive short essays by Coates in The Atlantic about his response to Baldwin’s nonfiction demonstrate the difficulty in pinning Baldwin down. “Baldwin’s writing is roughly contemporaneous with the Civil Rights movement, but he seems to share none of its hope, none of its belief in the power of love to conquer all,” Coates wrote in the first essay. Writing two days later: “My point is that after all of this—after all his hard talk—Baldwin is still talking about love.”

This year on January 18, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the most-viewed speech in America was Chris Rock’s recitation of “My Dungeon Shook.” Delivered at Harlem’s Riverside Church, about a mile west of Baldwin’s childhood neighborhood, the performance was remarkable both for Rock’s impassioned delivery and his omission of the essay’s most incendiary passage: “You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.” There remain limits to what even a figure as respected and outspoken as Rock can say on the subject of race in America today.

The audience in Riverside Church listened in reverent silence to Rock’s recitation for eight minutes before they interrupted him with applause. The outburst followed these lines:

The details and symbols of your life have been deliberately constructed to make you believe what white people say about you. Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear.

This is one theme that, in the recent flurry of reappraisal, has evaded emphasis. Baldwin did not only write about what it means to be black in America. He also wrote, as fearlessly as any American writer, about what it means to be white.

He approached the theme obliquely in his earliest essays. “Hatred,” he writes in the conclusion of “Notes of a Native Son,” “which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.” But in the racial stratification of American private and public life, hatred was only one ingredient—is only one ingredient (Baldwin’s work withstands translation to the present tense)—and not a necessary one. The country’s race nightmare could not be examined in isolation, like quadrennial election issues such as immigration policy or Social Security. Race was—is—the fundamental American issue, underlying not only all matters of public policy (economic inequality, criminal justice, housing, education) but the very psyche of the nation. “The country’s image of the Negro,” Baldwin writes in Nobody Knows My Name, “which hasn’t very much to do with the Negro, has never failed to reflect with a kind of frightening accuracy the state of mind of the country.”

That a country, especially one the breadth and size of the United States, should have a united “state of mind” may seem a rhetorical embellishment. But it was Baldwin’s point that the race problem was so ingrained that it did infect the entire nation, from its institutions of justice to the passing encounters of strangers on the sidewalks of major American cities.

No black American failed to grasp the severity of the problem. When white Americans did, it was—is—a symptom of profound self-delusion. In The Fire Next Time, Baldwin put it this way: “Whatever white people do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves.” This denial—and anyone who accepts the status quo is guilty of it—is as corrosive as hatred. It is corrosive because it requires purposeful blindness.

Baldwin was alluding to the blindness of Robert Kennedy, who could not see why an African-American man who came of age during Jim Crow might not feel inspired to sacrifice his life for his country in Vietnam. He was talking about the inability of white Americans to understand that Elijah Muhammad drew a devoted following not because he spoke about racial separatism but because he spoke about power. Baldwin was also addressing the blind devotion of many white Americans to the national mythology, “that their ancestors were all freedom-loving heroes, that they were born in the greatest country the world has ever seen, or that Americans are invincible in battle and wise in peace, that Americans have always dealt honorably with Mexicans and Indians….”

Advertisement

While civil rights activists emphasized the cost of racism to its victims, Baldwin emphasized the cost to those in power. “In the face of one’s victim,” he writes in Nobody Knows My Name, “one sees oneself.” A nation that refused to treat or even acknowledge a cancer that had metastasized throughout its entire body could not be considered free. Nor could it see the rest of the world clearly. What moral authority could America assert abroad when its own people were so bitterly divided? This is the point that Baldwin made to Kennedy at the attorney general’s apartment at 24 Central Park South in 1963.

Baldwin wrote his essays from a novelist’s perspective, which is to say with a surfeit of empathy and a sensitivity to inner contradiction. The essay that made his reputation, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” was itself an assault on novelists who confused fiction for polemic, and botched both jobs in the process. He understood that in good fiction, as in real life, there tend not to be sentimental heroes and cruel villains but only deeply compromised human beings who struggle with their sins and shortcomings as best they can. He made this point in “Preservation of Innocence,” an obscure 1949 essay unavailable in book form until it appeared in the Library of America’s Collected Essays. Though he was discussing homosexuality, the point applies to race. “A novel insistently demands the presence and passion of human beings, who cannot ever be labeled,” he wrote. “Without this passion we may all smother to death, locked in those airless, labeled cells, which isolate us from each other and separate us from ourselves.” Labels were a source of the problem.

The occasional white devil does appear in his novels: the racist cop who taught Rufus Scott “how to hate” in Another Country; the racist cops who pull over a young Leo Proudhammer and his brother in Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone; the racist cop who vindictively targets Fonny in If Beale Street Could Talk. But these are relatively incidental, walk-on parts. In his more involved treatments of the theme, his characters are nuanced, well-intentioned but flawed, human.

In Another Country, three different interracial romances (Rufus and Eric; Rufus and Leona; Ida and Vivaldo) are undone from within by racial anxieties. In each relationship, it is the black character whose love is poisoned by doubt, and who suffers most bitterly. In Tell Me How Long the situation is reversed. Barbara King is a white actress who tries to escape the influence of her wealthy Kentucky family by fleeing to New York, where she falls in love with Leo. But the casual, condescending racism of the bohemian theater scene undermines their union. Barbara is invited to summer stock; Leo is asked to be the company’s driver. “Barbara and I were marooned, alone with our love, and we were discovering that love was not enough—alone, we were doomed.” When they split, which seems inevitable from the start, Barbara bears the greater cost. “I was discovering what some American blacks must discover,” says Leo, “that the people who destroyed my history had also destroyed their own.”

The self-destructive qualities of bigotry are most vividly evoked in the one novel Baldwin wrote that contained no black characters. In Giovanni’s Room, when David falls in love with Giovanni, and they move in together, he feels alive, free, despite his sexual confusion and shame. When his fiancée Hella returns to Paris, he abruptly leaves Giovanni and renounces their love. “What kind of life can two men have together, anyway?” As he makes his shallow arguments, denying his own love, he feels himself becoming robotic, cruel, cold—not only to Giovanni but also to Hella. “All that had once delighted me seemed to have turned sour on my stomach,” he says. “I think that I have never been more frightened in my life…. Something was gone; the astonishment, the power, and the joy were gone, the peace was gone.”

The passage recalls the conclusion of “Stranger in the Village,” where Baldwin argues that America’s insistence on racial division requires a crippling degree of self-delusion. “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction,” he writes, “and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.” The sentiment was put more succinctly in a comment made by Martin Luther King, overheard at a party by Baldwin, that “bigotry was a disease and that the greatest victim of this disease was not the bigot’s object, but the bigot himself.”

Baldwin made the racial question personal, reducing a society-wide problem to a matter of one’s private conscience. He was not alone in this approach, but he was alone in bringing a novelist’s sensitivity to bear on it. In Baldwin’s writing racism is, among other things, a failure of empathy. If the tendrils of race reached into all aspects of American political social life, so too did it reach into the deepest recesses of the heart. In “A Word from Writer Directly to Reader,” a short statement included in a fiction anthology edited by Herbert Gold (and collected more than half a century later in The Cross of Redemption), Baldwin was asked whether the age in which he wrote made special demands on him as a writer. “The difficulty,” he replied,

is to remain in touch with the private life. The private life, his own and that of others, is the writer’s subject—his key and ours to his achievement. Nothing, I submit, is more difficult than deciphering what the citizens of this time and place actually feel and think. They do not know themselves….

How do people come to know themselves? One way is by reading fiction. The profound act of empathy demanded by a novel, forcing the reader to suspend disbelief and embody a stranger’s skin, prompts reflection and self-questioning. But most people don’t read novels. In his essays and public speeches, Baldwin tried to create a similar effect through allegory and metaphor. At times he reduces the nation to the size of an individual (speaking, for instance, of the American “state of mind”); elsewhere he elevates the individual to the level of an entire race. Baldwin went so far as to suggest that the racial anxieties of white America derive from the most primal, universal fear of all: fear of death. “White Americans do not believe in death,” he writes in The Fire Next Time, “and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.” It is difficult to take this literally—it requires, first of all, that you accept his claim that black people have no fear of death—but as metaphor it stands to reason that confronting the subject of racial iniquity requires questioning one’s most basic assumptions about the workings of American democracy. Can a system of representation be said to be successful when equal representation is denied to so many?

One of Baldwin’s favorite allegories was of the dead body hidden in plain sight. He published a version of it in “Notes for a Hypothetical Novel” (included in Nobody Knows My Name), but he put it more directly in a 1961 conversation with Malcolm X:

If I know that any one of you has murdered your brother, your mother, and the corpse is in this room and under the table, and I know it, and you know it, and you know I know it, and we cannot talk about it, it takes no time at all before we cannot talk about anything. Before absolute silence descends. And that kind of silence has descended on this country.

Baldwin, in his nonfiction, often recalled scenes from his own life in which he was forced to confront this choking silence. In an essay about Martin Luther King written around this time he describes visiting Montgomery a year after the bus boycott. “I have never been in a town so aimlessly hostile, so baffled and demoralized,” he writes. (A recent stay in Montgomery left me with the impression that, while less openly hostile, the city remains baffled and demoralized.) Baldwin decides to ride the bus. He sits “just a little forward of the center of the bus” while some black passengers sit closer to the driver. The white passengers endure this affront “in a huffy, offended silence.” The black protesters had disrupted the natural order of things, causing bafflement and hurt. Without the image of a subservient black class, “the whites were abruptly and totally lost. The very foundations of their private and public worlds were being destroyed.” Few writers more explicitly described the way racist policy contributed to personal trauma, not only for the victims but, to a lesser but still-significant extent, for the empowered.

Silence is another word for ignorance. If in the last five decades the silence around race has decreased in some places—college campuses, hashtag activist feeds, municipal politics in cities like Baltimore, New Orleans, and New York—it has thickened in others. As Baldwin said, you can judge the state of a society’s education level by the quality of its political speeches. By that standard, it feels like an understatement to say that our national intelligence has never been more degraded. When the ignorance is heavy, the silence about race inhibits honest conversations about war, terrorism, financial inequality, immigration, health care. The result of this can be seen in any presidential debate of this cycle.

Baldwin’s novels and essays describe a nation suffering from a pain so profound that it cannot be discussed openly. This was not a pessimistic view; it was, rather, deeply optimistic. It suggested that most people, deep down, wanted to resolve the crisis—that they were not apathetic or, in Baldwin’s term, brutally indifferent. Today it can be difficult to preserve this optimism. Still there are strong indications that there is more pain than indifference. You can tell this by the general level of fear, which is, after all, the source of that pain. It has risen to the surface, often reaching the level of total panic, evident in the calls to “take our country back,” to “reignite the promise of America,” to “abolish the IRS,” to “restore America’s brand,” and the many other revanchist sentiments that dominate the political discourse. These messages do not ring of indifference. They are expressions of great terror.

Last year, without much public notice, the United States crossed a threshold: for the first time in history, more than half of the nation’s public school students belonged to racial minorities. What happens when the majority and the minority trade places? Do the categories break down? Will there be fire this time? We’ll soon find out. For now, we can do no better than turn to Baldwin for our answer:

Majorities [have] nothing to do with numbers or with power, but with influence, with moral influence, and I want to suggest this: that the majority for which everyone is seeking which must reassess and release us from our past and deal with the present and create standards worthy of what a man may be—this majority is you. No one else can do it.

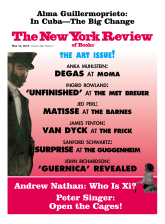

This Issue

May 12, 2016

Cuba: The Big Change

A Different Guernica

-

1

Edited by Douglas Field, Justin A. Joyce, and Dwight A. McBride, published by Manchester University Press. ↩

-

2

Spiegel and Grau, 2015; reviewed in these pages by Darryl Pinckney, February 11, 2016. ↩