1.

Whether we gain or not by this habit of profuse communication it is not for us to say.

—Virginia Woolf, Jacob’s Room (1922)

Every technological revolution coincides with changes in what it means to be a human being, in the kinds of psychological borders that divide the inner life from the world outside. Those changes in sensibility and consciousness never correspond exactly with changes in technology, and many aspects of today’s digital world were already taking shape before the age of the personal computer and the smartphone. But the digital revolution suddenly increased the rate and scale of change in almost everyone’s lives. Elizabeth Eisenstein’s exhilaratingly ambitious historical study The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979) may overstate its argument that the press was the initiating cause of the great changes in culture in the early sixteenth century, but her book pointed to the many ways in which new means of communication can amplify slow, preexisting changes into an overwhelming, transforming wave.

In The Changing Nature of Man (1956), the Dutch psychiatrist J.H. van den Berg described four centuries of Western life, from Montaigne to Freud, as a long inward journey. The inner meanings of thought and actions became increasingly significant, while many outward acts became understood as symptoms of inner neuroses rooted in everyone’s distant childhood past; a cigar was no longer merely a cigar. A half-century later, at the start of the digital era in the late twentieth century, these changes reversed direction, and life became increasingly public, open, external, immediate, and exposed.

Virginia Woolf’s serious joke that “on or about December 1910 human character changed” was a hundred years premature. Human character changed on or about December 2010, when everyone, it seemed, started carrying a smartphone. For the first time, practically anyone could be found and intruded upon, not only at some fixed address at home or at work, but everywhere and at all times. Before this, everyone could expect, in the ordinary course of the day, some time at least in which to be left alone, unobserved, unsustained and unburdened by public or familial roles. That era now came to an end.

Many probing and intelligent books have recently helped to make sense of psychological life in the digital age. Some of these analyze the unprecedented levels of surveillance of ordinary citizens, others the unprecedented collective choice of those citizens, especially younger ones, to expose their lives on social media; some explore the moods and emotions performed and observed on social networks, or celebrate the Internet as a vast aesthetic and commercial spectacle, even as a focus of spiritual awe, or decry the sudden expansion and acceleration of bureaucratic control.

The explicit common theme of these books is the newly public world in which practically everyone’s lives are newly accessible and offered for display. The less explicit theme is a newly pervasive, permeable, and transient sense of self, in which much of the experience, feeling, and emotion that used to exist within the confines of the self, in intimate relations, and in tangible unchanging objects—what William James called the “material self”—has migrated to the phone, to the digital “cloud,” and to the shape-shifting judgments of the crowd.

2.

The present discordant and distracted twitter…

—Virginia Woolf, Reviewing (1939)

When the smartphone brings messages, alerts, and notifications that invite instant responses—and induces anxiety if those messages fail to arrive—everyone’s sense of time changes, and attention that used to be focused more or less distantly on, say, tomorrow’s mail is concentrated in the present moment. In Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), an engineer named Kurt Mondaugen enunciates a law of human existence: “Personal density…is directly proportional to temporal bandwidth.” The narrator explains:

“Temporal bandwidth” is the width of your present, your now…. The more you dwell in the past and future, the thicker your bandwidth, the more solid your persona. But the narrower your sense of Now, the more tenuous you are.

The genius of Mondaugen’s Law is its understanding that the unmeasurable moral aspects of life are as subject to necessity as are the measurable physical ones; that unmeasurable necessity, in Wittgenstein’s phrase about ethics, is “a condition of the world, like logic.” You cannot reduce your engagement with the past and future without diminishing yourself, without becoming “more tenuous.”

Judy Wajcman, in Pressed for Time, identifies the “acceleration of life in digital capitalism” not as something radically new but as an extension of earlier technological changes. “Temporal disorganization” has always put different kinds of pressure on different social groups, and the culture of digital interruption places different kinds of stress on the interrupted (employees, children) and the intruders (managers, parents) leaving both unhappy, like Hegel’s mutually constrained slaves and masters.

Advertisement

Wajcman is more sanguine about relations among equals: teenagers use messaging services to open private channels of communication after encountering one another in the shared arena of social networks; they make a snap judgment of someone else’s online profile, then follow it with extended online contact uninterrupted by work or play. But Wajcman oversimplifies, for example, the benefits of using smartphones to reschedule dinner dates at the last moment, “thereby facilitating temporal coordination.” As Mondaugen’s Law predicts, that same flexibility reduces (in Pynchon’s words) both “temporal bandwidth” and “personal density” by weakening one’s commitments to the future, even trivial ones.

Computers and smartphones bring to daily life some of the qualities of another artifact of the digital era: the video game in which a player sustains an anxious state of vigilance against sudden unpredictable intrusions that must be dealt with instantly at the risk of virtual death. This too has its benefits: drivers who grew up playing video games are reportedly quicker than others to respond to sudden danger, more capable of staying alive.

Dante, always our contemporary, portrays the circle of the Neutrals, those who used their lives neither for good nor for evil, as a crowd following a banner around the upper circle of Hell, stung by wasps and hornets. Today the Neutrals each follow a screen they hold before them, stung by buzzing notifications. In popular culture, the zombie apocalypse is now the favored fantasy of disaster in horror movies set in the near future because it has already been prefigured in reality: the undead lurch through the streets, each staring blankly at a screen.

3.

How can I proceed now, I said, without a self, weightless and visionless, through a world weightless…

—Virginia Woolf, The Waves (1931)

The most socially alarming effect of the digital revolution is the state of continuous surveillance endured, with varying levels of complaisance, by everyone who uses a smartphone. Bernard Harcourt’s intellectually energetic book Exposed surveys the damage inflicted on privacy by spy agencies and private corporations, encouraged by citizens who post constant online updates about themselves. “We are not being surveilled today,” he writes, “so much as we are exposing ourselves knowingly, for many of us with all our love, for others anxiously and hesitantly.” In place of the medieval idea of the king’s two bodies—the king’s royal powers derived from heaven and his natural self—Harcourt proposes the two bodies of “the liberal democratic citizen…: the now permanent digital self, which we are etching into the virtual cloud with every click and tap, and our mortal analog selves, which seem by contrast to be fading like the color on a Polaroid instant photo.” (This seems accurate about common feelings, but overestimates the likelihood of digital immortality; in fact vast Web-based communities, with all their history, have been swept away with a click.)

Harcourt draws heavily on Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975) in his account of today’s “expository society.” Unlike Jeremy Bentham’s never-built nineteenth-century panopticon analyzed by Foucault, where all-knowing, all-powerful jailers observed unknowing, unwilling prisoners, everyone in Harcourt’s expository society of Twitter posts and Instagram feeds can spy on everyone else and with few exceptions everyone wants to be spied on. A new kind of celebrity, perceived both as enviable and appalling, comes to those whose only talent is for insistent self-exposure. Worst of all, for Harcourt, is the knowing compliance of today’s consumers with forms of censorship and control once in government hands but now, for better or worse, practiced by corporations. The Apple Store, gateway for all software accessible to iPhone users, blocks apps designed specifically to display politically sensitive matter like pictures of drone strikes. “Apple, it seems, has taken on [the] state function of censorship, though its only motive seems to be profit.”

After Harcourt’s book appeared, Apple and the state came into conflict when the FBI tried to force Apple to make it possible to decrypt a terrorist’s iPhone. Apple holds to the largely admirable view that it should provide no means to invade anyone’s privacy, while its software is designed to intrude on everyone’s privacy with messages, ads, alerts, and notifications, and to record and sell everything spoken to the phone’s built-in “digital assistant,” all in the name of convenience and profit.1 The knowledgeable and elite can reduce these intrusions to the extent that Apple permits, and the strong-willed can turn off their phones, but Apple relies on everyone else’s passive acceptance of interruption and eavesdropping in order to keep its profitable data moving.

Harcourt describes a new kind of psyche that seeks, through its exposed virtual self, satisfactions of approval and notoriety that it can never truly find. It exists in order to be observed; it must continually create itself by updating its declared “status,” by revealing itself in Facebook narratives and Instagram images, while our “conscientious ethical selves” need to be reminded—by ourselves and others—to exist at all. Harcourt apparently does not expect such reminders to have much effect and concludes despairingly: “It is precisely our desires and passions that have enslaved us, exposed us, and ensnared us in this digital shell as hard as steel.”

Advertisement

Exposed interprets the Internet from a “conscientious ethical” perspective. Virginia Heffernan’s Magic and Loss interprets it aesthetically: “The Internet is the great masterpiece of human civilization.” Its magical quality is what Heffernan values most: “It turns experiences from the material world that used to be densely physical…into frictionless, weightless, and fantastic abstractions.” She has learned to favor digitized MP3 audio files whose “encoded sounds coolly defied the material reality of music” and the immersive world enclosed in a virtual reality headset, which “decidedly does not feel like reality.”

Harcourt’s book is a despairing protest against domination; Heffernan’s is an ecstatic narrative of submission. Magic and Loss entwines her own story with that of the Internet, her escape from “our most sacred class values,” from a world where “the Atlantic and the New Yorker serve as the old guardians, policing the borders of literacy,” into a classless world of pleasure and immediacy, where videos uploaded from the smartphones on which they were made are the universal nonverbal language and all things “are worth observing for the sheer joy of it.”

Exploring the Internet, she resisted, at first, leaving a world where flesh-and-blood writers and filmmakers wanted “to tell great stories” about people’s lives and entering a world where persons dissolved into virtuality: “I wasn’t ready yet to swap the ideal of the story for the ideal of the system.” The computer theorist Nicholas Negroponte had urged in Being Digital (1995) that we should (in Heffernan’s words) “embrace our status as information bits rather than atoms of matter,” and now a machine was overcoming her resistance: “This was the iPod’s magic: it transformed me and made me digital.” She explains her merger with the machine by citing Aquinas on “the sharing of a nature with another.”

She writes near the start of the book that, living as we do in the joyously shifting unreality of the Internet, “we need to…scrap our old aesthetics and consider a new aesthetics and associated morality.” But by the end, she is increasingly conscious of what she let herself lose when long private talk via copper-wired telephone, talk shared by two voices speaking at least in part from their inner lives, gave way to the visual simulacra of Snapchat and Instagram: selfies, not selves. Her unexpectedly moving final chapter retells her life history from a different perspective, as a quest for religious meaning sought variously through conversions to Judaism and back to Episcopalianism and academic authorities encountered in classrooms and on Twitter.

Her closing paragraph imagines “the mysterious and maddening Internet” throwing off like a meteor shower “a measure of amazing grace.” But the effect is merely aesthetic: “It works even if you don’t believe in it.” In the paragraph that precedes this, looking past the grace of aesthetic immediacy, she writes that the Internet “stirs grief: the deep feeling that digitization has cost us something very profound,” through alienation from voices and bodies that can find comfort in each other.

Digital connectedness, she concludes, “is illusory;…we’re all more alone than ever.” Death itself, glimpsed through “a fathomless and godlike medium that doesn’t suffer,” is “more harrowing than ever.” But these terrors are not specific to the digital age; nor are they the product of the Internet. They afflict everyone who has ever tried to live in an intense aesthetic spectacle—as in Bernard Harcourt’s expository society of digital simulacra that exist to observe and be observed—rather than a vexed community of “conscientious ethical selves.”

4.

It is certain that an opinion gains greatly as soon as I know that someone is convinced of it; it gains veracity.

—Novalis, “Das allgemeine Brouillon” (1798–1799)

The crowd has always been the field in which isolation dissolves, even among strangers, and the individual will merges into collective impersonal force. The protective distance that human beings maintain between themselves and others—their personal space—typically varies among cultures and personalities, but disappears entirely in a crowd where everyone is pressed together in one undifferentiated mass. The oldest form of the crowd, Elias Canetti wrote in Crowds and Power (1960), is the “baiting crowd” that forms in order to kill someone, a crowd that today pleases itself by taking selfies while cheering a political candidate’s murderous fantasies.

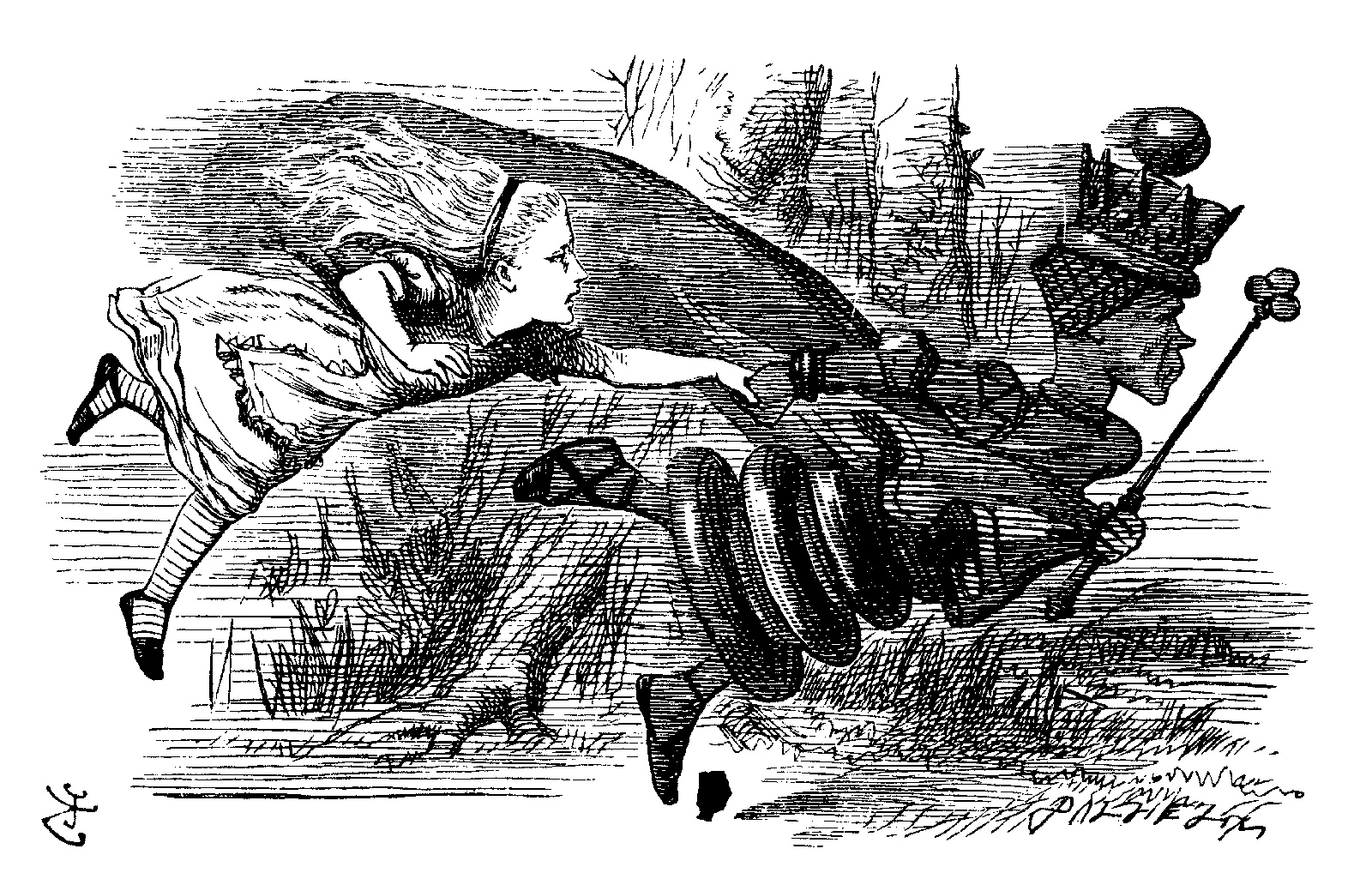

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s Updating to Remain the Same, using a different vocabulary from Canetti’s, describes the ways in which the habit of making and seeking “updates” of our own and other people’s status creates a similar crowd: “Through…habits, individual actions coalesce bodies into monstrously connected chimeras.” The Internet, in Chun’s account, is a world always in crisis, in panic at the latest e-mail viruses, pursuing, for example, an elusive Ugandan warlord merely by viewing an immensely popular YouTube video about him. Crises create change; but the habit of constant updating of one’s Facebook status, always reusing a familiar conventional syntax, paradoxically leaves everything the same. “To be is to be updated”: one must update in order to give “evidence of one’s ongoing existence.” Hence Chun’s subtitle: “Habitual New Media.”2 The Internet, in its vastness, induces a sense of personal powerlessness that can be relieved by joining a crowd—until the crowd reshapes itself, as it always does, and must be joined again. As the Red Queen told Alice, “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

Like Judy Wajcman, though far less lucidly, Chun describes an online world of (again in Pynchon’s phrases) thin temporal bandwidth and tenuous personal density. She reports intelligently on the persistent fantasy of online “friends,” a fantasy in which a wished-for community may coalesce by force of habit into a virtual crowd, centering on “a relentlessly pointed yet empty, singular yet plural YOU.”

Richard Coyne, in Mood and Mobility, portrays in elegant prose a networked world more nuanced, personal, and responsive than the chimeras Chun analyzes in hip-sociologese, but Coyne acknowledges the same unpleasant truths that Chun insists upon: machines change the deepest experience of life; “space is filled with devices and technologies that really do have a role in the way moods happen,” by providing “mood-altering entertainment” that can “incite people to action, protest, and revolution”—or induce “existential vertigo…or habituation.”

Chun explores a variety of causes that make the Internet more habitual than innovative. A further cause, not mentioned in these books, is suggested by research into the ways that reading on screen differs from reading on paper. Like all attempts to quantify personal experience, published studies in this field show questionable and inconsistent results, but at least one report plausibly suggests that when you read on paper you are more likely to follow the thread of a narrative or argument, whereas when you read on screen you are more likely to scan for keywords. This is a variant of Virginia Heffernan’s distinction between her old ideal of “story” and her new ideal of “system.”

Reading for keywords—though I doubt that research studies can say anything definitive about it—may have the effect of confirming in a reader the associations that those keywords already hold. So a reader who sees the words “immigration” or “abortion” on screen may end up with stronger feelings about them, not with the potentially different ideas, originating from a different person, that someone might get when reading an argument about the same words on paper. The implications of this effect on recent political life—the furies aroused, for example, by Donald Trump’s Twitter feed—will not escape anyone’s notice. Anger feeds on itself to produce greater anger; polarities of opinion become intensified; individual voters coalesce into baiting crowds; virtual enmities erupt into physical ones.

In The Filter Bubble (2011), Eli Pariser attributed this narrowing effect to technologies used by Google, Amazon, Apple, and others to feed search results, or suggestions of books and music that might “also interest” you, that match and confirm information that you searched for earlier, and that others who have been associated with you by algorithms also searched for. Left- or right-wing users are nudged by onscreen links to books and sites that endorse the views they already hold. Pariser’s argument, though much disputed, seems essentially unchallengeable, and a comparably narrowing effect may be produced not only by corporate machinations but also by new habits of online reading.

The digital world makes once-unimaginable amounts of information available to everyone, while it also transfers to the network and the crowd what had once been matters of personal knowledge and personal judgment. This change began before the digital era; one trivial but telling example is the decline of the single-author restaurant guide—written by someone with a distinctive set of personal preferences—and its replacement by the crowd-sourced guides, printed or online, pioneered by the Zagats. Wikipedia relies on “consensus” as the final arbiter of content, rather than a ruling board of supposedly expert editors, as in, say, the Columbia Encyclopedia. Wikipedia’s continual give-and-take corrections work well for math and science, less well for history and literature where consensus is sometimes ill-informed. Dubious romantic or heroic stories about larger-than-life figures like W.B. Yeats or Ernest Hemingway cannot be dislodged because consensus favors familiar myths.

The expanding “Internet of things” gives a smartphone user remote control over a home heating system hundreds of miles away. The psychological effect, for everyone I know who uses these devices, reproduces the stress felt by managers who can demand obedience from subordinates at all times: greater control over things too distant to touch brings greater anxiety about matters otherwise too distant to worry about. Perhaps Philip Howard will be proved right in his forecast, in Pax Technica, that new device networks, feeding information about everything to centralized databases, will “bring about a special kind of stability in global politics, revealing a pact between big technology firms and government, and introducing a new world order.” He forecasts that the winners in the new order will be those “who can demonstrate truths through big data gathered over the internet of things and disseminate those truths over social media,” and the losers will be those “whose lies are exposed by big data.”

But this view requires a utopian faith in the rational, autonomous judgment of everyone whose lives are shaped by firms and governments, and by the “monstrously connected chimeras” that unite them. The moral purposes of governments and tech firms are the central issue omitted from such predictions, and the book’s concluding nostrums (“Do one thing a month to improve your tech savvy”) are little help where questions of value are what matter.

5.

I sing the body electric….

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1855)

Everyone grows up in a climate of erotic expectation and imagination shaped by their culture. The Internet radically transformed that climate, so that those who went through puberty before, say, the 1990s took for granted different erotic expectations from those who went through puberty afterward. A climate in which young people’s sexual imagination was largely private and secretive gave way to a climate in which everyone grew up with publicly available images of women as willingly degradable and discardable, hard and soft porn displaying bodies with improbable textures and shapes.

Every culture has its own special distortions of sexuality, and the distortions of the digital era are mirror opposites of (in J.H. van den Berg’s phrase in The Changing Nature of Man) “the nineteenth century’s derangement of sexuality.” Many middle-class Victorian men had troubled, incapable sexual relations with middle-class women because the men associated sexuality with their degraded social inferiors, and idealized the “pure” women of their own class. Middle-class Victorian women fainted, it seems, when their ordinary sexual desires came into intolerable conflict with a culture that impressed on them a conviction that those desires were degrading.

Today, young men again report troubled, incapable relations with women entirely unlike the women in the vivid images they grew up with. Middle-aged commentators complain that young women are emotionally fragile to a degree unknown thirty years ago; but this ignores the psychological pressures of a new erotic climate in which ordinary sexual desires are again, as they were in the nineteenth century, brought into inward conflict with a culture that portrays them as degrading. The supposed “empowering” effect of teasingly erotic music videos by Miley Cyrus or Beyoncé seems to have, for many viewers who are not celebrities, the same whistling-in-the-dark unreality of an earlier generation’s “self-esteem” programs. The psyche has not become more fragile; instead, the pressures to which it is subjected are in many ways more forceful and obtrusive than they have been for more than a century.

Like every other aspect of the digital world, the new sexual climate brings both benefits and losses. Today, almost no one need be shamed by any variety of desire that once would have been permanently isolating. The same public world that offers a shared community for every specialized form of hatred also, for the first time, offers a shared, sympathetic community for every variety of love. As in social media and messaging, a newly open public realm also opens new avenues for private intimacy.

Meanwhile, the body is taught to find new extensions of itself. Apple, Samsung, and others foresee great profits in systems that use sensors in a “smart watch” or wristband to record the wearer’s physiological data for corporate processing. Software can now tell you how well you slept last night, supplementing your subjective sense of yourself with reliably objective measurements, and subtly outsourcing your everyday bodily senses in a different way from, for example, an annual blood test. No one has offered a clear idea of the effects of such procedures.

6.

This soul, or life within us,…is always saying the very opposite to what other people say.

—Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader (1925)

Every technological change that seems to threaten the integrity of the self also offers new ways to strengthen it. Plato warned about the act of writing—as Johannes Trithemius in the fifteenth century warned about printing—that it would shift memory and knowledge from the inward soul to mere outward markings. Yet the words preserved by writing and printing revealed psychological depths that had once seemed inaccessible, created new understandings of moral and intellectual life, and opened new freedoms of personal choice. Two centuries after Gutenberg, Rembrandt painted an old woman reading, her face illuminated by light shining from the Bible in her hands. Substitute a screen for the book, and that symbolic image is now literally accurate. But in the twenty-first century, as in Rembrandt’s seventeenth, the illumination we receive depends on the words we choose to read and the ways we choose to read them.

-

1

See Sue Halpern, “The Real Legacy of Steve Jobs,” The New York Review, February 11, 2016. ↩

-

2

Addiction is the extreme case of habit. See Jacob Weisberg, “We Are Hopelessly Hooked,” The New York Review, February 25, 2016. ↩