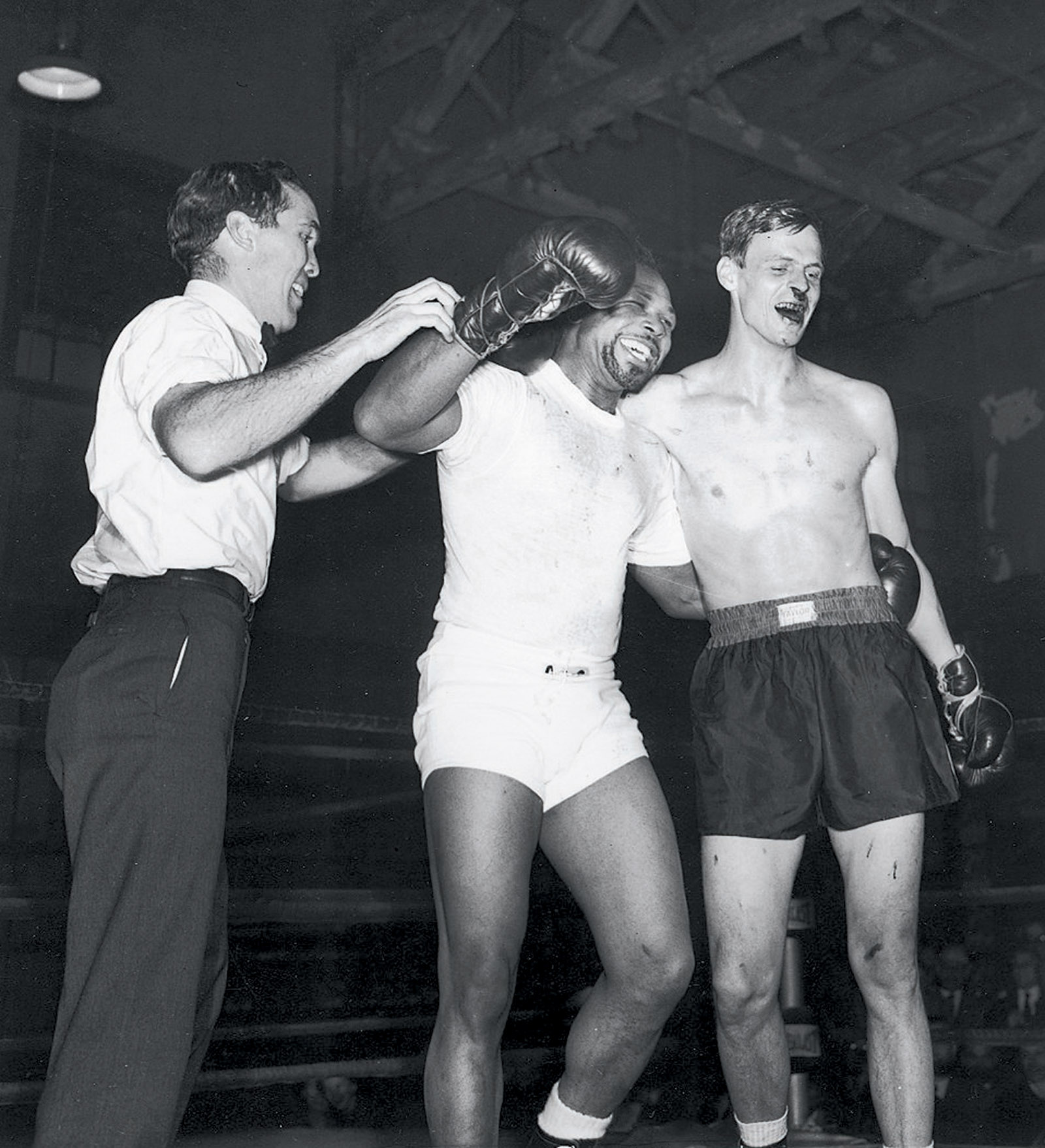

Herb Scharfman/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

George Plimpton, right, after a boxing match with Archie Moore at Stillman’s Gym, New York City, 1959; Ezra Bowen, the Sports Illustrated editor who acted as referee, is at left. ‘Quite visible are the effects Archie Moore left on the author’s nose,’ Plimpton writes in Shadow Box, ‘what would have been described in the jaunty style of the mid-nineteenth century as follows: “Archie dropped a hut’un on George’s sneezer which shook his ivories and turned the tap on.”’

Six books and several dozen Sports Illustrated articles into his journalistic career, George Plimpton still couldn’t type the words “participatory journalism” with a straight face. “‘Participatory journalism’—that ugly descriptive,” he writes in the first pages of Shadow Box (1977), sighing over his Underwood. Though he became nationally known as the subgenre’s paragon and the term pursued him into his obituaries, Plimpton was only a journalist in the sense that James Thurber was an illustrator and Robert Benchley a newspaper columnist. He went places, spoke to people, and wrote down his observations, but the reporting wasn’t the point. What was the point? The storytelling, the humanity, the comedy.

It was an odd match to begin with: for a writer of Plimpton’s background, journalism ranked on the literary hierarchy somewhere below light verse and pulp westerns. In George, Being George, Charles Michener, Plimpton’s editor at The New Yorker, explained:

Journalists were from a rougher background. They tended not to be Ivy League, white-shoe boys, which George was certainly the epitome of. When I came into that world, I was at Yale and people would say, “Why do you want to be a journalist? It’s sleazy. That isn’t for people like you.”

Journalism was not to be taken seriously, but comedy writing was even more of a joke. What was the president of the Harvard Lampoon, class of 1948, to do?

After two years at Cambridge, where Plimpton earned a master’s in English, he moved to Paris to run a fledgling literary quarterly, while working in secret on various novels he would later abandon; one began with a long set piece in which a fire breaks out at a society party. As contemporaries and friends—Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Gay Talese—began to revitalize the journalistic form, placing themselves in the middle of the story and writing with the depth, nuance, and narrative richness of novelists, Plimpton saw an opening.

In 1956 he began writing for Sports Illustrated, which Henry Luce had founded two years earlier with the hope of targeting men of leisure. The editors had as much interest in hunting, boating, and polo as in the major spectator sports; the main athlete profiled in the debut issue was the Duke of Edinburgh, an enthusiastic amateur archer, cricketer, and high jumper. The first significant paid writing assignment of Plimpton’s career was a 30,000-word cover story, published over four consecutive issues, about Harold Vanderbilt’s passions for yachting and bridge.

The refined approach required refined authors. Sports Illustrated’s founding editor, Sid James, who had previously edited Ernest Hemingway at Life, sought novelists to serve as contributors: William Faulkner covered hockey and the Kentucky Derby, John Steinbeck wrote about fishing, Budd Schulberg about boxing, James T. Farrell was the roving baseball correspondent, and John P. Marquand wrote a series about country clubs. The editors also touted the return of Paul Gallico, who had been the highest-paid sportswriter in New York as a columnist for the Daily News before abandoning his post to write novels and screenplays (the best known today are The Poseidon Adventure and The Pride of the Yankees). Gallico got his start as a young journalist by sparring a round with Jack Dempsey, who knocked him out cold in about ten seconds. Gallico repeated the gag with many of the professional athletes he covered in order, he wrote, to understand more intimately “the feel” of the game. In the opening pages of Out of My League (1961), Plimpton writes of his admiration for Gallico:

He described, among other things, catching Herb Pennock’s curveball, playing tennis against Vinnie Richards, golf with Bobby Jones, and what it was like coming down the Olympic ski run six thousand feet above Garmisch—quite a feat considering he had been on skis only once before in his life…. I wondered if it would be possible to emulate Gallico, yet go further by writing at length and in depth about each sport and what it was like to participate.

Thus marks the first appearance of “participate” in Plimpton’s writing.

Little, Brown has published in attractive Skittles-colored editions a slightly eccentric selection of Plimpton’s works of sports journalism. The one for which he is best known, “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch,” which was the cover of Sports Illustrated’s April 1, 1985, issue and was later expanded into a novel, is omitted, perhaps because it is a work of fiction (though his other books, it should be noted, contain plenty of fiction). Also missing is One More July (1977), a conversation with the offensive lineman Bill Curry, and The X-Factor (1990), an inquiry into what distinguishes superstar athletes from mortals, a quality he discussed as early as the opening paragraph of his Vanderbilt piece. The new set includes the five books that Plimpton counted as works of “participatory journalism”—Out of My League, Paper Lion (1965), The Bogey Man (1968), Shadow Box, and Open Net (1985)—as well as Mad Ducks and Bears (1973), a weightless postscript to Paper Lion that mainly concerns the off-field hijinks of two Lions linemen, and One For the Record (1974), which follows Henry Aaron’s quest to beat Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record. But all of Plimpton’s books were participatory in the sense that he is always tangibly present, his sensibility—beguiling, lyrical, charming, deeply funny—singing from every paragraph. The joy of these books comes less from sharing the company of Muhammad Ali or Alex Karras than—a point lost on his many imitators—from sharing the company of George Plimpton.

Advertisement

Paul Gallico wasn’t the first writer to hit upon the participatory premise. As Jane Leavy points out in her foreword to Out of My League, Mark Twain went surfing in 1866 on assignment for the Sacramento Union (he wipes out instantly) and Dickens wrote about hiking Mount Vesuvius for his Daily News (at the brim of the volcano his clothing bursts into flames). Plimpton devotes a chapter in Shadow Box to a history of amateurs, many of them writers, challenging professional boxers, including A.J. Liebling, socked by Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, and Ernest Hemingway, who, rumored to have sparred with Gene Tunney, “had such an ugly time that he never talked about it.”

The best account comes from the turn of the century, when the British heavyweight champion, Bombardier Wells, was deposed by a Frenchman, Georges “the Orchid Man” Carpentier, in seventy-three seconds. In a drunken sulk, the members of the British National Sporting Club decided that the only way to avenge the humiliation was to put up one of their own members against Carpentier. Should an amateur last longer in the ring than Wells, their national dignity would be restored. A letter was dashed off to Carpentier, offering as challenger the club’s best amateur boxer, a family man from Yorkshire named George Mitchell:

Carpentier wrote back by return mail. He said he would be delighted to accept the challenge. The bravado of the whole thing pleased him.

Nothing is recorded of Mitchell’s reaction. I have imagined him just finishing his breakfast, his clubmates rushing in with the news from the morning post, slapping him on the back, brandishing the letter from Paris, cries of “Bully for you, George,” while in truth he sat there with his eyes staring, a piece of breakfast muffin crumbling in his fingers.

Plimpton knew a good premise when he saw one. But the Lampoon veteran realized that Gallico had failed to capitalize as fully as he might have. An amateur competing against a professional was amusing, but it was funnier when these competitions were heightened by a jolting disjunction of class status; the humor in the Mitchell anecdote lies in “Bully for you,” “brandishing,” and “breakfast muffin.” Plimpton peppers his own misadventures with similar flourishes. Before his bout with Archie Moore, “the Old Mongoose,” the editor of The Paris Review prepares by visiting the library of the Racquet Club, “on Park Avenue,” where he settles into “one of the library’s large leather chairs” and tucks into an 1807 volume called The Art and Practice of English Boxing. The selection suits him: his sensibilities are vaguely Edwardian in nature.

At the Detroit Lions’ training camp in Paper Lion, where he sings the Harvard fight song during initiation, he notes that his “eastern seaboard cosmopolitan accent” strikes his baffled teammates as “British.” His prose is affably patrician and bemused throughout, Evelyn Waugh’s Tony Last among the Amazonian savages in A Handful of Dust. The brutal collisions at the line of scrimmage during the Lions’ practice remind him of the sound of “someone shaking a sack of venetian blinds.” In The Bogey Man, a dangerously errant drive draws a reaction “not unlike the looks received when [a] demitasse cup is dropped on [a] crowded patio floor.”

The quintessential Plimptonian anecdote comes near the end of Paper Lion when, a year after leaving the team, he wistfully follows his old squad from afar. We find him in Bellagio, on Lake Como, chasing down a box score in a Paris Herald he has found at a waterside café. “When I read that the Lions had lost a game,” he writes, “I rose in anguish out of my chair, absolutely stiff with grief, my knee catching the edge of the table as I came up, and toppling it over in a fine cascade of Perrier bottles.” The Perrier waterfall even surpasses the crumbling breakfast muffin.

Advertisement

Philip Roth, in the extended appreciation of Plimpton that appears in Exit Ghost, identified the issue of social class as “the deepest inspiration for his writing so singularly about sports, cagily venturing into situations where he plays at being bereft of his class advantages (except for the upper-crust manners, which, in a world wholly alien, if not hostile, to good breeding, he knowingly employs for the comic effect of their unsuitability).” But the technique only works because Plimpton hides this knowing quality from his readers. There is never a wink or nod in the direction of the premise’s artifice. A consummate straight man, he emphasizes how seriously he is taking matters.

Upon joining the Lions he begs team officials not to give him away to his teammates, hoping somehow to blend in. “I’d like to be thought of as just another rookie,” he tells them, “an odd one maybe, but no special favors or anything because I’m a writer.” When he proposes a match against Muhammad Ali, he earnestly emphasizes to the boxer that he will train very hard. “You mean,” says a baffled Ali, “I’m supposed to hit you?” In the locker room at Yankee Stadium, minutes before pitching to the National League All-Stars, Plimpton can’t bring himself to interview any of the players lest he reveal himself to be an outsider. Instead,

I began to strengthen the fiction as the afternoon progressed by adopting a number of curious mannerisms I associated with ballplaying: my voice took on a vague, tough timbre—somewhat Southern cracker in tone—and the few sentences I spoke were cryptic yet muffled; I created a strange, sloping, farmer’s walk; once I found myself leaning forward on my knee, spiked shoe up on the batting-cage wheel, chin cupped in hand, squinting darkly toward center field like a brooding manager; I was sorely tempted to try a stick of gum, despite my dislike of the stuff, in order to get the jaws moving professionally. Sometimes I just moved the jaws anyway, chewing on the corner of my tongue.

The threat of severe bodily injury offers the highest dramatic stakes, which is to say, the best comedy. Boxing is the purest version of the premise though the books about football and hockey both contain scenes in which Plimpton must sign a contract absolving the team of responsibility for “any injuries, suffering, or death which may occur as a result of my participation.” Open Net, in which he poses as a goalie, begins with a lengthy discussion of the accuracy and speed with which a professional can shoot a puck into a goalie’s head. In Paper Lion, Plimpton is greeted at camp by players who show off the gruesome deformities they’ve endured over their careers. One player exhibits a knee that “no longer had the outlines of a kneecap, but seemed as shapeless and large in his leg as if two or three handfuls of socks had been sewn in there.” “Holy smoke,” says Plimpton.

To heighten the danger Plimpton plays up his physical fragility and ineptitude. He describes himself in Paper Lion as built “very lean and thin, along the lines of a stick,” in Shadow Box “rather like a bird of the stiltlike, wader variety—the avocets, limpkins, and herons,” in Open Net as “the quintessential ectomorph.” He skates across the rink in his goalie equipment “with the ponderous gait of a dowager coming down a church aisle.” Plimpton was, in fact, a born athlete—Roth remembers touch football games “in which George threw spirals as accurate as any a pass receiver could hope for in any league.”

At times a reader can’t help but be impressed by his accomplishments, despite his efforts to undermine them. The humor at the end of Out of My League—Plimpton, exhausted to the point of hallucination from throwing a game’s worth of pitches to a lineup of All-Stars, is pulled from the mound halfway into his appearance by a concerned coach—is diminished slightly by the reader’s belated realization that Plimpton has somehow managed to retire five of eight All-Stars, including Willie Mays on an infield pop-up and that year’s MVP, Ernie Banks, on a routine fly ball. That’s better than Yankee pitcher Bob Turley fared against the same lineup when he started that year’s All-Star game, allowing four of the first seven batters to reach base and two runs to score.*

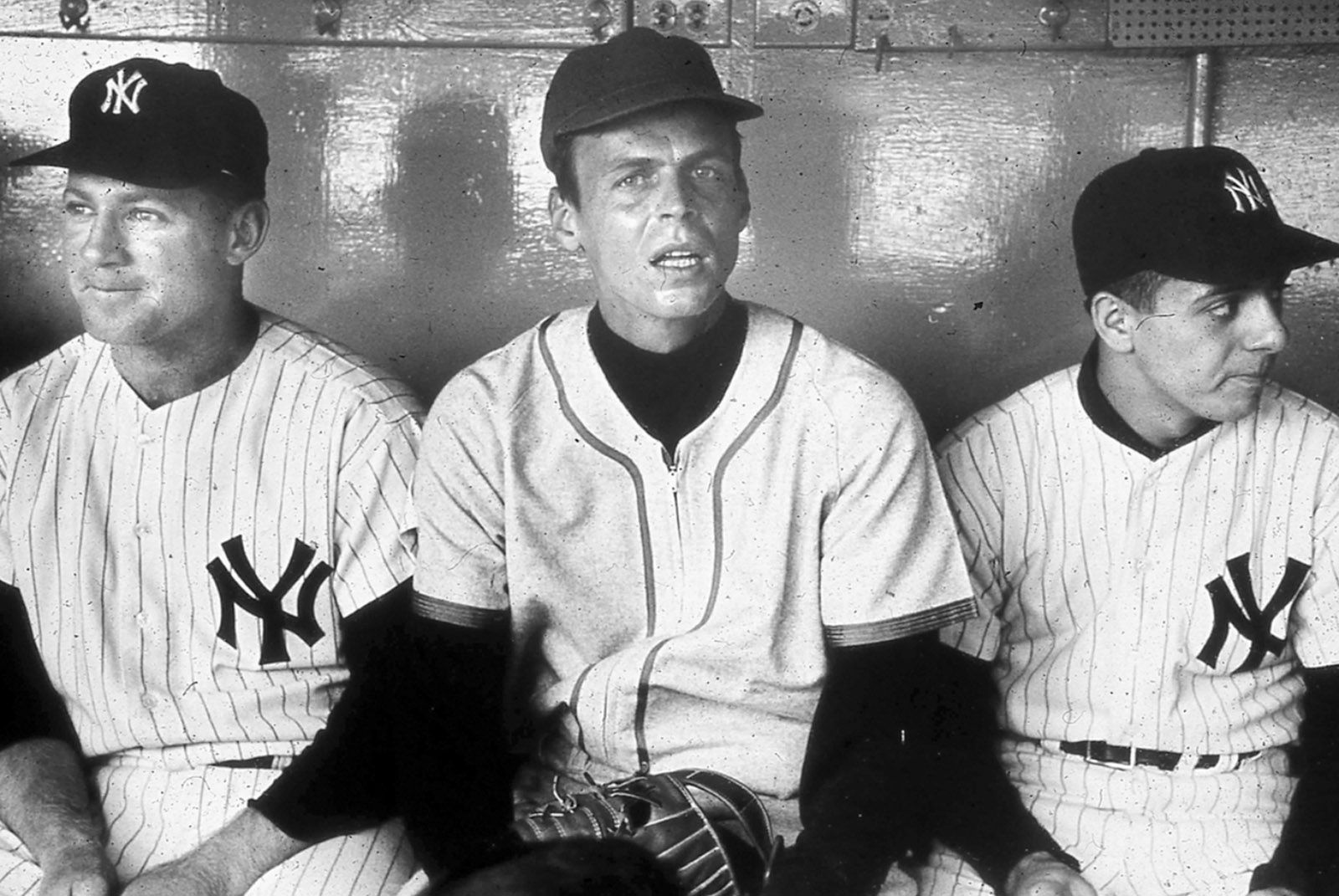

Garry Winogrand

‘Flanked by Whitey Ford and the Yankee batboy just after my ordeal,’ Plimpton writes in Out of My League. ‘The photograph was snapped as I dropped down between them—providing an accurate study of shock, in my case, and justified amusement from the ballplayers. They were not at all displeased that their profession had treated me as roughly as it had.’

The contact sports may test him physically but golf poses Plimpton his most severe test as a writer. In The Bogey Man, when he joins the PGA Tour for three tournaments on the Pacific Coast, he lacks his usual disadvantages. There is no risk of bodily harm; the handicap system (Plimpton’s is a generous eighteen) allows amateurs to compete with the pros on a level playing field; and the author is perfectly at home in the country clubs in which he finds himself. Various PGA champions and celebrities on the tour, many of whom he seems to know from New York, are always waving him over during cocktail hour. A caddy even mistakes him for a pro. Plimpton has never had it so tough.

His solution is to rely more heavily on historical anecdotes (many of which seem invented) and extended fantastical interludes as funny and imaginative as anything in Sidd Finch. One of these is inspired by a story about a golfer named Carl Lohren who was accidentally abandoned in “some little hick town” when he jumped out of his driving partner’s car at a railroad crossing to practice his swing. Plimpton imagines a screwball comedy in which Lohren, with only his club as protection, becomes caught in the middle of a local feud and is mistaken for a hired assassin. “Now, stranger,” says one of the natives. “What you got them shoes painted blue for? And what about them spikes? And what does that scribblin’ on your hat say?”

“I’m a golfer,” Lohren protests, “I’m the home pro at the Chippequa National Links Club. That’s what it says on the hat….”

Plimpton must also go deeper within himself, plumbing his own insecurities and shortcomings for material—an approach suited to a sport in which the player’s greatest foe tends to be oneself. “My woes in golf,” he begins the book, “I have felt, have been largely psychological.” Plimpton finds a suitable tournament partner in the gloomy Bob Bruno, a fringe player on the Tour, who has the habit, after a failed shot, of disappearing into the nearest wooded area to wrap his iron around the trunk of a eucalyptus tree. But even the greats struggle with greatness. “The hardest thing for a great many people is to win,” says Arnold Palmer, when Plimpton asks about the game’s mental challenges. “They get scared. And they doubt. Which gets them into trouble.” As a person born with a vanishingly low social handicap, Plimpton could empathize with the perils of high expectations.

Sports memoirs, like humor collections, rarely outlive their authors, but Plimpton’s books have aged gracefully and even matured. Today they have the additional (and unintended) appeal of vivid history, bearing witness to a mythical era that, as Rick Reilly writes in his foreword to The Bogey Man, “historians classify as ‘Before Insurance Lawyers Ruined Everything.’” (Journalists might classify it as Before Fact-Checkers Ruined Everything.) Plimpton writes about baseball locker rooms “heavy with cigarette and cigar smoke,” star players humbled by their off-season jobs (Pro-Bowler Alex Karras fills jelly doughnuts), and teams that cheat by positioning a spy with binoculars on a roof near the opponent’s practice field. He is able to convince major league All-Stars to take part in his scheme by offering, to the players on the team that gets the most hits off him, a reward of $125, the equivalent today of about $1,000. (By comparison, the Detroit Tigers’ slugger Miguel Cabrera earned $19,000 per inning this season.) It was also an age in which the press was powerful enough to convince professional teams to grant full, unfettered access to a journalist. Today a writer for a major national magazine is lucky to be allowed more than one hour with the subject of a cover article. Plimpton spent a full month living in a dormitory with the Lions.

As enjoyable as it is to read about Plimpton being treated roughly by professional gladiators in front of large crowds, the participatory approach also has its journalistic benefits. He understood that within every professional athlete is an amateur who, through some combination of born talent and luck, is surprised to find himself elevated to divine status. As a writer who, after the success of Paper Lion, was a bigger celebrity than most of his subjects, Plimpton had a special sensitivity to the hidden vulnerabilities of giants.

The weigh-in ceremony before Cassius Clay’s first championship fight against Sonny Liston is best remembered for Clay’s rumbling taunts, but Plimpton notes that Clay’s pulse was taken at 180; the doctor concluded that he was “scared to death.” We learn that Roger Maris, after the stress of breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, changed his batting style the following year to avoid reliving the experience. Plimpton devotes a chapter in One for the Record to the pitchers who allowed the most famous home runs in baseball history. Ralph Branca tells him that, after yielding “The Shot Heard Round the World,” he left the Polo Grounds to find his sobbing fiancée waiting for him in the parking lot with a priest. Branca’s second career, Plimpton notes, was in life insurance.

Much of the pleasure in reading Plimpton comes from his close observations: the delirious bliss with which the Lions consume lemonade after practice, the carpeting in Ali’s home garage, the way Aaron steps into the batter’s box “as if he were going to sit down in it somewhere,” or the view from the goalie’s net of the surreal, interminable “expanse of ice…a few people standing around in it like statuary in a winter landscape.”

Yet Plimpton’s purest journalistic assignment, One For the Record, has a glaring observational deficiency. Aaron’s main antagonist during his quest for the home run title was not Ruth’s ghost but the racial hostility of baseball fans. So much hate mail was sent to him that the US Post Office awarded him a plaque for receiving the highest volume of mail of any civilian. The FBI investigated multiple death threats, a bodyguard accompanied him to the field, and there was even an attempted kidnapping of his daughter. “It still hurts a little bit inside,” Aaron later said, “because I think it has chipped away at a part of my life that I will never have again. I didn’t enjoy myself. It was hard for me to enjoy something that I think I worked very hard for.”

Plimpton only alludes to the racial tension on a couple of occasions, an absence made more obvious by the book’s minimal length, which is padded by an eight-page photo insert and a superfluous fifty-two-page appendix that lists every home run hit by Ruth and Aaron. It was left to Mike Lupica to discover that during the famous home run trot, Aaron’s bodyguard watched from the right-field bleachers, gripping a pistol, debating whether to fire at the two white college students who leapt onto the field to chase Aaron around the bases. “What if I had decided to shoot my two-barreled .38 at those two boys,” the bodyguard told Lupica, “and had hit Hank Aaron instead, on the night he hit No. 715?”

Plimpton made sure not to miss the larger story in Shadow Box, which is not only his most seriously reported book but also his most personal (Lupica provides the foreword). Though it begins with the Archie Moore stunt, which occurred nearly twenty years earlier, it is primarily an intimate account of Ali’s career—his first championship, his conversion to Islam, the loss to Joe Frazier, his banishment from boxing for refusing to serve in the Vietnam War, and his stunning redemption against George Foreman in Zaire. In the darkened bar of a black motel in Miami, Malcolm X, a recent addition to Ali’s entourage, lectures Plimpton on the teachings of Elijah Muhammad. When Plimpton tries to change the subject by asking what he does for exercise, Malcolm X responds with a denunciation of commercial sports. “The Negro never comes out ahead—never one in the history of sport.” Plimpton politely points out that Ali might be an exception.

Plimpton is aboard Ali’s bus from Miami to Chicago after the first Liston fight in 1964 when it pulls into a truck stop near the Florida-Georgia border. Ali declines to enter the restaurant but his cornerman and confidant, Bundini Brown, enters, accompanied by Plimpton and a few other white journalists. “We have a place out back,” says the manager. “Separate facilities.” Bundini is furious: “The heavyweight champion of the world, and he can’t get nothing to eat here.” Ali enters the diner and drags Bundini out by his jacket, calling him a fool and worse. In the parking lot Ali keeps it up, whooping with delight, leaping into the air, taunting his friend. “Don’t you know when you not wanted? Face reality and dance!” Bundini breaks down, crying, but Ali won’t let up. His response is sickening and triumphant, victorious and defeated, cruel and defiant—a human response that tells us as much about his character as anything written about him.

Shadow Box is loosely structured, accommodating not only the familiar historical anecdotes but digressions into Plimpton’s own obsessions and curiosities: an unusual gangland heist, a survey of writers’ thoughts about death, a feud between Kenneth Tynan and Truman Capote, his doting relationship with Marianne Moore, and adventures in Havana with Ernest Hemingway. In these episodes Plimpton drops the persona that Roth describes as the “self-mocking double—the working journalist” and seems to appear as himself, or as close as he ever allowed in his writing.

In Out of My League he paraphrases Roy Campanella, saying that “you had to have an awful lot of little boy in you to play baseball for a living.” The sentiment is repeated in many of the books: “There are not so many better ways of fooling around,” says Lions’ quarterback Earl Morrall, while on the ice with the Bruins Plimpton observes that “few sports seemed to be enjoyed as much by its players as hockey.” Plimpton evokes the thrill of sports and the camaraderie they inspire as well as anyone has. But the fun is fleeting. When Plimpton enters the clubhouse in Yankee Stadium after his ordeal, he feels the joy slipping away fast. “The baseball diamond and the activity of the players, now engaged in their regular game, seemed unfamiliar and removed,” he writes. “It all seemed not to have happened.” It’s the same feeling an adult has upon looking back at childhood, the old sensations barely visible through the haze of years—sensations that can only be relived through dreams or, in the rarest of cases, literature.

This Issue

October 13, 2016

The Green Universe: A Vision

The Dangerous Financing of Colleges

-

*

In fairness, the damage to Plimpton’s pitching line might have been worse had he been allowed to issue walks in his exhibition; it took him twenty-three pitches to retire Banks. ↩