1.

For three decades, roughly since the end of the cold war, American foreign policy has been the subject of a passionate battle among three groups with radically different views of the part the United States should play in the world and of whether force or diplomacy should be its primary method.

Neoconservatives, who were passionate advocates for the Iraq war, want the United States to be the world’s policeman, concerned not only with states’ external behavior but with their internal adherence to American values, which, they believe, the United States should impose principally through the use of force. They care little for international agreements, believing that bad guys will flout them and good guys don’t need them.

Liberal internationalists, most of whom are supporting the current nuclear agreement with Iran, also want the US to act globally. But they want to build an increasingly strong international system of cooperation and alliances and avoid unilateralism. They see international progress deriving from increasing interdependence and agreed-upon rules to which the United States, however exceptional it may be, must adhere.

For realists, international relations are propelled by powerful states promoting their own self-interest. This view holds that the US should concentrate on its relations with the other great powers and on the balance of power in the most important regions and not waste resources on other parts of the world. Generally, realists argue for a much more limited US involvement in the conflicts of the Middle East.

The global financial crash of 2008 at America’s hands, the rise of ISIS, the transformation of Russia under President Vladimir Putin into a dangerous and committed adversary marked by its 2014 annexation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine, nuclear weapons programs in North Korea and Iran, cyber interventions in the US election, and a steadily more nationalistic and militarily provocative China—all of these have dramatically raised the stakes of these conflicts over policy. The crux is no longer in deciding how far America should reach in deploying its power and forcing its values on others, but in what it must do to meet a cascade of challenges to its core interests and national security.

Into this particularly dangerous moment comes Donald Trump. What he has done is to take the few things on which neocons, realists, and liberal internationalists agree and throw them out the window. These are fundamentals of American foreign policy, taken as givens by both parties for the seven decades since the close of World War II. They include, first, the recognition of the immense value to the security of the United States provided by its allies and worldwide military and political alliances.

Second, there is the belief that the global economy is not a zero-sum competition, but a mutually beneficial growth system built on open trade and investment. Since the 1940s the United States has invested in the growth of the world economy out of considered self-interest, believing that it was building growing markets for itself that would operate under a set of rules that it wished to live by. And third, Americans of all political stripes have believed that while authoritarian governments may temporarily enjoy greater freedom of action than governments that have to consider public support, in the long run democracy will prove superior. Dictators have to be tolerated, managed, or confronted, not admired.

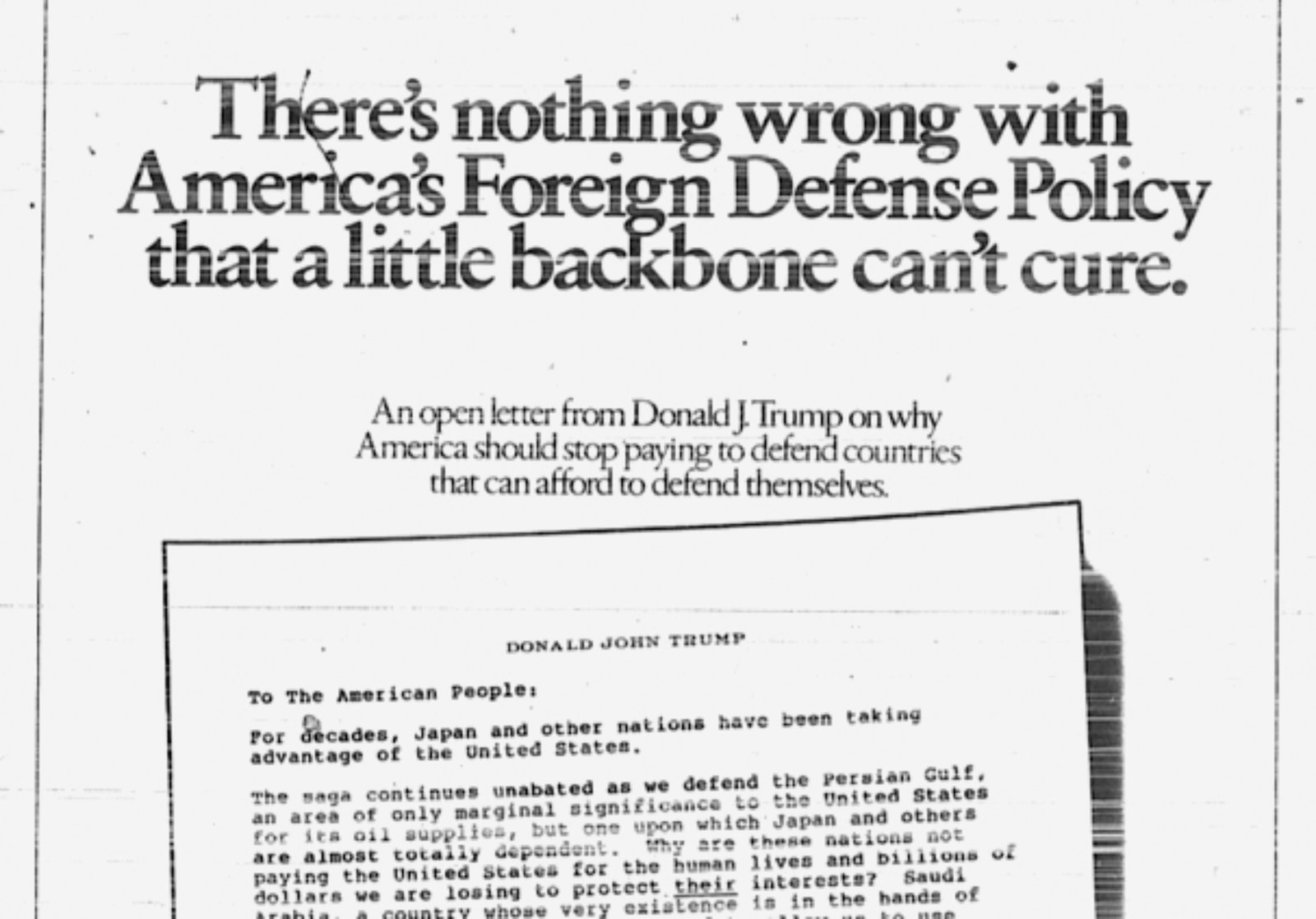

Trump’s foreign policy often seems invented in the moment—a mixture of impulse and ignorance amid a morass of contradictions. But in fact its essence, the opposite of the three core beliefs I’ve cited, has been remarkably consistent for decades.* In 1987, either toying with the possibility of a presidential run or building publicity for the forthcoming publication of The Art of the Deal (or both), Trump paid to publish an open letter to the American people in The New York Times and two other major papers with the headline “There’s Nothing Wrong with America’s Foreign Defense Policy That a Little Backbone Can’t Cure.”

Other nations, he wrote, “have been taking advantage of the United States.” They convince us to pay for their defense while “brilliantly” managing weak currencies against the dollar. “Our world protection is worth hundreds of billions of dollars to these countries”; yet weak American politicians respond “in typical fashion” to “these unjustified complaints.” “End our huge deficits,” he concludes, “reduce our taxes, and let America’s economy grow unencumbered by the cost of defending those who can easily afford to pay us for the defense of their freedom. Let’s not let our great country be laughed at anymore.”

In a 1990 interview he returned to the same theme: “We Americans are laughed at around the world for losing a hundred and fifty billion dollars year after year, for defending wealthy nations for nothing…. Our ‘allies’ are making billions screwing us.” The same is true for Europe: “Pulling back from Europe would save this country millions of dollars annually…. These are clearly funds that can be put to better use.” Asked, as recently as last April, if he believed that the US gains anything from its bases in East Asia, he answered, “Personally I don’t think so.”

Advertisement

Trump’s admiration for strongmen showed up in praise of Putin in 2016 and previously of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi. “Instead of having terrorism all over the place,” he said in February 2016, “we’d be—at least they killed terrorists, all right?” We find similar sentiments in 1990 in Trump’s criticism of then Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev for weakness, and his praise for China’s handling of the Tiananmen Square uprising: “The Chinese government almost blew it. Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength.”

The views Trump published in 1987, when he was forty-one, have not changed with time: mercantilist economic views; complete disdain for the value of allies and alliances; the conviction that the world economy is rigged against us and that American leadership is too dumb or too weak to fix it; admiration for authoritarian leaders and the view that the United States is being “spit on,” “kicked around,” or “laughed at” by the rest of the world. Critics of President Obama might say that Trump’s language was deserved, but these comments were directed at Ronald Reagan.

Trump’s core views don’t align with any of the current approaches to foreign policy I’ve mentioned. Their close relatives are to be found in Charles Lindbergh and the America Firsters’ admiration for dictators, the mercantilist and isolationist policies of Robert Taft, also in the 1940s, and the similar views of Patrick Buchanan twenty years later.

Beyond the narrow scope of Trump’s doctrines, what more is there to his foreign policy? One answer lies in the views of those he has chosen as his leading advisers. Foremost among them—at least for now—is retired Army Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, principal foreign policy spokesman during the campaign and named early in the transition as White House national security adviser.

In The Field of Fight, coauthored with Michael Ledeen, Flynn asserts that the United States is facing an “international alliance of evil countries and movements that is working to destroy us.” This “working coalition,” centered on Iran, also includes North Korea, China, Russia, Syria, Cuba, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. Cooperation among these countries derives from the shared hatred of the United States, which “binds together jihadis, Communists, and garden-variety tyrants.” No evidence is offered in support of this bizarre fantasy.

The United States must “energize every element of national power in a cohesive synchronized manner—similar to the effort during World War II” to fight this new “global war.” The radical Islamists, Flynn writes, “think they’re winning, and so do I.” Things are so dire, in fact, that “I’m totally convinced that, without a proper sense of urgency, we will be eventually defeated, dominated, and very likely destroyed.” So far, “our leaders in Washington, from the White House to the Pentagon to our major military headquarters, have proven they aren’t up to” fighting this war.

Iran is at the heart of Flynn’s fevered vision. The strictly limited, multilateral nuclear agreement signed in 2015 has been criticized by some for not going beyond the nuclear issue. Flynn and Ledeen transform it into a full-scale “strategic embrace of the Islamic Republic” by the United States. Focusing on the nuclear issue is, in any case, a mistake since, they argue, the goal of US policy should be regime change. Instead of invading Iraq in 2003, “our primary target should have been Tehran,…and the method should have been political—support of the internal Iranian opposition.” That this could have brought down the deeply entrenched Iranian government is another pure fantasy. But “we should at least consider how to change Iran from within, remembering that such methods brought down the Soviet Empire.” (They didn’t.)

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Flynn writes, have been fought in a “half-assed” manner, with “token” forces and without the resolution “to crush our enemies.” To win we have to destroy all ISIS and al-Qaeda bases, conquer the terrorities they hold, return them to local control, and then, somehow, “insist on good governance.” It was a “pipe dream” to believe we could bring full democracy to this region (not clearly defined, but including, at least, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Kurdish areas), but “we could certainly bring order.” Order and good governance have, of course, been the elusive goals of a decade and a half of multitrillion-dollar effort.

“Eliminating Radical Islam” will take leadership that “isn’t obsessed with consensus.” The only consensus that matters is “the one at the end” of what Flynn emphasizes will be a war extending for generations. Awash in tweets and twenty-four-hour news coverage, he yet writes, “things have not changed much since Machiavelli told his prince ‘if you are victorious, the people will judge what ever means you used to have been appropriate.’”

Advertisement

Flynn does part company with Trump (and, perhaps, with Secretary of State designate Rex Tillerson) in a major way regarding Russia. “There is no reason to believe Putin would welcome cooperation with us,” he writes. The Kremlin’s 2016 announcement of its intention to open new military bases on its western border and its plan to increase the readiness of its nuclear forces “are, rather, indications that Putin fully intends to do the same thing as, and in tandem with, the Iranians: pursue the war against us.”

Trump’s statements have been much friendlier, to say the least, toward Russia. But it’s easy to see what Trump would find attractive in Flynn’s fact-free bluster. Moreover, Flynn was the first big-name (or, at least, not completely obscure) national security figure to join his campaign, bringing badly needed credibility, for which Trump owes him a good deal. Yet this book reveals a man so utterly out of touch with the real world at home or in the Middle East that it’s hard to believe even Trump could take him seriously for long, or that a man whose former military colleagues now call him “unhinged” will survive very long in the critical position to which he has been named.

2.

Though most are Republicans, neoconservatives have been among Trump’s most outspoken opponents. The Johns Hopkins military historian Eliot Cohen has led that opposition. While they have obvious points of overlap with Trump’s belligerence, neocons believe in constant, active global engagement by the US to advance both American power and values. They object to Trump as a leader who would pull back from the world, who does not understand the critical elements of power, and who is uninterested in promoting freedom and democracy.

Whenever there is a pause between military engagements, neocons tend to worry that America’s credibility—and therefore its security—is at immediate risk. Michael Ledeen (Flynn’s coauthor) is known for the “Ledeen Doctrine” (a term coined by Jonah Goldberg):

Every ten years or so, the United States needs to pick up some small crappy little country and throw it against the wall, just to show the world we mean business.

In exactly this vein, in The Big Stick Cohen posits that the invasion of tiny Grenada in 1983 helped restore American credibility after Vietnam. Recovery of American credibility today “will probably occur only when the United States actually does something to someone—wiping out a flotilla of Iranian gunboats,” for example.

An obsession with regime change in the Middle East—especially Iran—is another constant for neocons. Cohen was among the first to advocate invading Iraq and Iran and overthrowing other governments in the region as well—dubbing the effort “World War IV.” In his current book he offers a tepid defense of the US invasion but in the end admits that “the Iraq war was a mistake. The publicly articulated premise of an active and dangerous Iraqi weapons of mass destruction program was false.”

Unfortunately, his intellectual honesty does not extend to Iran. Throughout, he refers to Iran as a state in which nuclear weapons are impending. “The heart of Iran’s emerging military potential lies in its nuclear program,” he writes, without acknowledging that the elements of that program have been almost entirely removed, shut down, or subjected to around-the-clock inspection for at least fifteen years. “Once Iran does have nuclear weapons”—not “if,” but “when.” And again, “a nuclear- armed Iran will, eventually, pose a direct threat” to the US—not “would,” but “will.” This is not a matter of semantics. It will be a tragedy for the United States and the world if the conviction that Iran will always outsmart us leads to a failure to enforce the international nuclear deal or to an active American effort to undermine it.

Except for his failure to deal with the threat to the planet from climate change, one cannot quarrel with Cohen’s list of the principal dangers that immediately confront the US: China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, Islamist terrorism, and the ungoverned threats from uses of cyberspace and from nations in chaos. These dangers, however, vary disconcertingly in urgency from chapter to chapter. In the chapter on China, which Cohen believes is America’s greatest threat, Russia is “doom[ed] to long-term decline.” In the chapter on Russia, Iran, and North Korea, these three pose a greater threat than the possibility of major interstate war in Asia. In each of these countries he sees

a more dangerous erosion of norms, a routine simmering of war along numerous disputed borders, and the potential for the escalation of conflicts into much bigger and unanticipated disputes in which nuclear weapons could eventually come into play.

Does he imagine that a major war between the US and China would be nonnuclear?

Cohen sees a Chinese desire to establish hegemony in East Asia and a much more debatable intent to “reshape an international order in its image.” China’s combination of military and economic strength creates an unprecedented strategic problem for the US since even at the height of the cold war Russia was economically weak. Beijing’s aggressive encroachment in the South and East China Seas is a “potential trigger of global war.” Only a beefed-up “American force structure, alliance system, and mobilization capacity” will be able to deter it. But Cohen stops short of asking to what end this build-up should be directed. Should the United States try to restore its dominance in East Asia, or should its goal be to achieve a stable equality with a rising China?

In the West, Cohen writes, Putin is determined to reestablish Russia’s sway over its neighbors and to weaken and “perhaps ultimately destroy NATO.” Russia will do whatever it can by means of cyber- and information warfare to undermine NATO and the EU through the election of right-wing governments that would block both organizations’ ability to act. Cohen urges the permanent stationing of “substantial” US forces in Poland and the Baltic States and meeting Russia measure for measure in the use of propaganda and information warfare. Like Flynn, he argues that we need to greatly improve our willingness and ability to wage a “war of ideas” as we did in the cold war, this time against both Russia and Islamist extremists. It is not clear, however, just which of the many things he rightly objects to in Russian behavior he would have the US respond to in kind.

Overall, Cohen argues for “a substantially larger” US military, steadily funded at a cost of 4 percent of GDP (compared to 3.3 percent currently). While the US could afford that amount, the metric is misleading because the politically relevant measure is not the size of the national economy but the size of the federal budget. That choice, by Congress and the public, is what makes any particular level of defense spending affordable or not. Once the cost of entitlements and payments on the federal debt are met, defense spending that is 20 percent larger than today’s could, in a stable or smaller overall budget, force enormous cuts in the entire range of federal discretionary spending.

Perhaps inevitably for a book on the uses of hard power, the uses of diplomacy are nearly ignored. Cohen briefly nods to conventional wisdom—“American military power is the handmaiden of American statecraft.” And he gives diplomats a part in the US offense—the job of finding ways to “expose, enhance, and exploit splits among its opponents…and to subvert governments” we don’t like. But the constructive role of statecraft as a way to shape an international environment that solves problems and avoids conflict is not considered. Inevitable conflict defines Cohen’s world, a deep distortion of even this dangerous time in international affairs.

Richard Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, has a very different perspective. He has written a study of statecraft practiced by a country that is not just supported by its own alliances but is also deeply embedded in a multilateral system that touches on all its interests. Like Cohen, he sees a challenging international environment, but one amenable to solutions on almost every front. His is a relentlessly practical, nonconfrontational, problem-solving approach. The book is as much about the process of diplomacy as it is about substance: its leitmotif is flexible, informal “consultations”—a word that appears over and over again. Haass generally puts practice—what is achievable in a particular situation—ahead of principle.

The differences between Cohen’s worldview and Haass’s nonideological, rules-based, liberal internationalist approach are evident everywhere. The two men, for example, would probably describe Russia’s subversion and invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine in equally derogatory terms. In response, Cohen seems to suggest providing more arms to Ukraine, an escalation that would never overcome the dominant position of Russia, Ukraine’s neighbor across a long, undefended border. Haass is right to quietly point out the obvious: that putting NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia on hold (neither comes close to meeting NATO membership requirements in any case) is part of the answer to this nasty situation.

Haass proposes what he sees as a fundamentally new concept of international relations. He calls it the “sovereign obligation” of states to individuals and states beyond their borders, in contrast to the traditional “sovereign responsibility” of states to citizens and conditions within their borders. This, he says, is Westphalian sovereignty updated for a globalized world. Actually, he calls it realism updated, lest anyone think him unaware of the continuing importance of major-power rivalry. But although he tries to underline its importance with the label “World Order 2.0,” sovereign obligation seems simply a description of a change that has been underway for several decades.

Borders haven’t disappeared, and won’t, but they have become more porous. Whether it’s fisheries or currencies, air pollution or information (including nuclear know-how), exploding levels of transnational investment or carbon dioxide, transnational crime or trade, just about the only resource that doesn’t cross borders more easily and in much greater volume today than decades ago is people. By acts of commission or omission, states impinge much more heavily on others. Governments have responded by adopting a huge variety of treaties, rules, agreements, codes of conduct, coalitions, conventions, accords, and ad hoc procedures. This is what the globalization of several decades has meant in practice: a constantly widening net of multilateral arrangements enfolding new issues and norms of behavior that cross borders.

3.

Like many realists, Trump thinks America does too much in the world and cares too much about others’ quarrels, suggesting that he will pull back its international engagements. Unlike realists, necons, or liberal internationalists, he doesn’t see the connection between America’s alliances and American security. He thinks money spent to strengthen other nations politically, economically, and militarily is wasted—a view that conflicts with those of Republican and Democratic presidents back to Truman and the Marshall Plan. On the other hand, “Make America Great Again” suggests a highly engaged superpower with the clout and the will to dictate events. We’ll “take their oil,” build a wall and force Mexico to pay for it, and “take out” terrorists’ families regardless of international law. We’ll force China to accept changed terms of trade, and if that causes a trade war, “who the hell cares.” We should “greatly expand” our nuclear forces and welcome the resulting arms race because “we will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

Some of this is surely posturing: shaking things up and trying to unsettle international opponents. Some is the result of ignorance that may be modified in office. Some is Trump’s well-established practice of beginning negotiations by taking something that has already been agreed to off the table and demanding a concession to put it back. This may occasionally work, but by and large what works in real estate deals is not transferrable to international negotiations. The One China policy he has questioned, for example, as Trump will discover if he tries to challenge it once in office, is simply not a bargaining chip for China. As Ambassador Nicholas Platt, a prominent China expert, put it, “One China is not a bargaining chip, it’s the table.”

Notwithstanding Rex Tillerson’s many international connections and geographically wide experience advancing the interests of ExxonMobil, and his statements at the confirmation hearings, the policies that the secretary of state–designate will likely follow on most of the issues that will confront him are going to remain a mystery until he begins to execute them. There is simply no record on which to base a prediction.

In the quietest of times Trump’s policies would be alarming enough. But this is, nearly all agree, a particularly dangerous time of rapid and fundamental change in the military, economic, and political dominance to which the United States is accustomed, exacerbated by Islamist terrorism and technological transformation. North Korea’s rapidly growing nuclear and long-range missile capability has barely made it onto most lists of threats the next president must confront, but it is an urgent menace for which there are few good answers. Moreover, the US has limited resources and much that demands fixing at home.

Public opinion doesn’t provide much guidance. In different spots in his book, Cohen quotes the opposed results from two Pew Research Center polling questions in 2014, apparently without noticing the contradiction. One found that “more than half of Americans believed that the United States was not doing enough to solve the world’s problems.” The other found that roughly half of respondents feel that the US “should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.”

Clearly this is a time for rethinking many long-established claims and convictions, and for new foreign policies. Who will provide them? As threatening as the external environment is, it could easily become much worse.

—January 12, 2017

This Issue

February 9, 2017

Was Snowden a Russian Agent?

The F Word

-

*

I am indebted to Thomas Wright for this insight. See “Trump’s 19th-Century Foreign Policy,” Politico, January 20, 2016. ↩