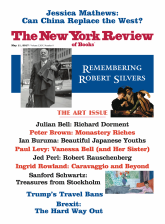

Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation/©Kara Walker

Kara Walker: The Emancipation Approximation (Scene #18), 1999–2000; from the exhibition ‘Emancipating the Past: Kara Walker’s Tales of Slavery and Power—From the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation’ on view at the University Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, through April 30, 2017

The “fierce spirit of liberty is stronger in the English Colonies probably than in any other people of the earth,” declared the great Irish statesman and author Edmund Burke to the British Parliament in 1775, urging conciliation and not war with the colonists. And the people of the American South, he continued, were attached to liberty “with a higher and more stubborn spirit” than those of the North. Southern slave-owners knew what bondage meant and thus valued their own freedom, including the freedom to oppress others, that much more strongly. “Such will be all masters of slaves, who are not slaves themselves,” Burke reflected. “In such a people, the haughtiness of domination combines with the spirit of freedom, fortifies it, and renders it invincible.”

George Washington was of that South, where ideals of liberty reinforced and were reinforced by a culture of buying, owning, and selling human beings. Furious that Great Britain was taxing the colonies without their consent, he urged resistance. “No power upon Earth can compel us to do otherwise,” he wrote, “till they have first reduced us to the most abject state of Slavery that was ever designed for Mankind.”

Did Washington notice the tragic irony? He told a manager of his Mount Vernon plantation in 1779 that it was “of very little consequence” to him if his property was in slaves or bank certificates, but it was slave labor, along with land speculation, that made him one of the richest men in Virginia. Still, he professed pity for “these poor wretches” and detested the idea of offering his slaves in a public sale. In 1794, he wrote of his earnest desire “to liberate a certain species of property which I possess, very repugnantly to my own feelings.” And by 1797, he wished “that the Legislature of this State could see the policy of a gradual Abolition of Slavery.”

Aware of the radical injustice of slavery and conspicuously protective of his own legacy, in his last will and testament the father of the country provided for the freedom of his slaves after the death of his wife Martha. He instructed that the oldest among them be well clothed and fed and that the youngest be taught reading, writing, and a useful trade. Only his valet William Lee was to be granted liberty immediately upon Washington’s death, with the promise of an annuity and the right to remain at Mount Vernon “as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.” Fearful that his family might obstruct his directions, Washington demanded that “this clause respecting Slaves and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled…without evasion, neglect or delay.”

George Washington stands tall in the historical record. Neither Thomas Jefferson nor James Madison expressed or demonstrated such concern and empathy for their enslaved servants. In her absorbing Ties That Bound, Marie Jenkins Schwartz, the author of Born in Bondage: Growing Up Enslaved in the Antebellum South (2000) and Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South (2006), focuses on the intimately intertwined lives of those three Virginian presidents, their wives and families, and their slaves.

The story of the Founders and slavery is one of the most vexed in American history, analyzed and debated generation after generation. Ties That Bound doesn’t unravel the moral or sociological underpinnings and consequences of those tangled connections, but it does contribute a fresh and valuable dimension to that long argument with its fine-grained portraits of domestic life in the South in the early republic. Building on the pioneering work of Annette Gordon-Reed, Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, and many other scholars, Schwartz adeptly demonstrates that, despite the masters’ and mistresses’ obeisance to the self-serving and self-protective myth that there existed a caring and mutually beneficial relationship between them and their slaves, neither the powerful nor the powerless were able to escape from the demeaning bonds of slavery.

Surrounded by slaves from childhood, Martha Washington viewed them as part of the furnishings of daily life. She grew up on her parents’ tobacco plantation in Virginia. Her father, Jack Dandridge, while still married to her mother Fanny, had a relationship with a slave that resulted in the birth of at least one child, Ann Dandridge, Martha’s enslaved half-sister. “Like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines,” commented the South Carolina writer Mary Boykin Chesnut, a caustic observer of southern mores in the Civil War era. “The mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children.”

Advertisement

Martha’s first marriage was to Daniel Parke Custis, a wealthy plantation owner whose father, John Custis IV, also had a child, Jack, with one of his slaves. Martha and Daniel eventually brought the young Jack (who died soon after) and Ann Dandridge to live in the Custis house. After seven years of marriage, Daniel died, leaving an estate that included thousands of acres of land in eastern Virginia and three hundred slaves, but no will. According to Virginia law, Martha was entitled to the use of one third of his estate and would serve as the steward of the rest until her children came of age.

She brought her inherited wealth to Mount Vernon when she married George Washington in 1759. She brought her children, Jacky and Patsy, too, as well as Ann. Circumstantial evidence, according to Schwartz, suggests that teenaged Jacky had a child with Ann, his mother’s half-sister. Their child, William, grew up in the Washington home, the light-skinned son of an enslaved mother. He was the only slave Martha ever freed. But before that the Washingtons treated him as if he were free; and although there was never a deed of manumission, his name was omitted from the list of Mount Vernon slaves.

While dutifully managing her various households in New York, Philadelphia, and Mount Vernon, Martha insisted on obedience and respect from her slaves. Her personal maid, the young Oney Judge, Schwartz writes, “learned to anticipate her mistress’s every demand, to stand aside when her mistress did not need her,” and to keep her “facial expression pleasant and friendly.” Martha scarcely recognized the humanity of her enslaved help. When a young child who belonged to her niece died, she advised her not to console the grieving family. “Blacks are so bad in thair nature,” she judged, “that they have not the least gratatude for the kindness that may be shewed to them.”

Though her house slaves worked from 4:30 in the morning until 8:00 at night—or after, if the Washingtons requested a late supper—Martha nevertheless groused that “they always idle half their time away.” Her maid and seamstress Charlotte, she complained, “will lay herself up for as little as any one will.” Still, when slave children frolicked in the gardens of Mount Vernon, disturbing the elaborate flower beds, George and Martha tolerated their playfulness. The Washingtons “walked a fine line when it came to discipline,” Schwartz comments. Slave owners “could employ violence, psychological pressure, or the threat of violence and sale to make slaves do as they were told,” and yet slaves were a reflection on their masters, displaying, through their behavior and manners, the refinement and beneficence of the family.

In their New York residence, at the outset of Washington’s presidency, George and Martha were served by slaves they had brought from Mount Vernon, setting a dismal precedent for his successors: seven of the next fourteen presidents elected before the Civil War—Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Tyler, Polk, and Taylor—would staff the White House with their slaves. When the nation’s capital moved to Philadelphia, the Washingtons again took slaves with them. But now there was a problem: in 1780, Pennsylvania had passed a law for gradual emancipation, stipulating that slaves brought into the state—for example, by southerners conducting business there—could, after six months’ residence, petition for freedom. “The idea of freedom might be too great a temptation for them to resist,” Washington coolly remarked, and so he and Martha decided to send their slaves back to Mount Vernon every few months in order to evade the law. Even so, in 1796 Martha’s maid Oney Judge fled the Washingtons’ Philadelphia home for freedom in New Hampshire, and later the president’s enslaved cook Hercules also escaped to freedom.

Martha Washington was faithful to her husband’s will, freeing the slaves he owned a year after his death. But except for William, the slave who may have been her grandchild, she left the slaves she had inherited from her previous marriage to the heirs of Daniel Parke Custis—Jacky’s children, Nelly and Wash, who would pass them on to their own children, one of whom would marry Robert E. Lee. George Washington’s nephew, Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington, inherited a large part of the Mount Vernon estate after Martha’s death. Unwilling to follow his uncle’s example, Bushrod made his own slaves understand that they had no hope of freedom upon his death. No member of George Washington’s family shared his disdain for slavery, leaving his final gift of freedom a solitary and noble act.

Perhaps not totally solitary. Thomas Jefferson freed a few of his slaves, but they included the children he fathered with his slave Sally Hemings. Sally was the half-sister and property of Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. Martha’s mother had died in childbirth, and her father, John Wayles, after being widowed twice more, turned to a concubine, his slave Betty Hemings, the light-skinned daughter of an English ship captain and an African woman. They had six children, including Sally.

Advertisement

In 1773, a year after Martha’s marriage to Thomas Jefferson, her father died, and she inherited Betty Hemings and her children—Martha’s half-siblings—and incorporated them into the slave culture at Jefferson’s Monticello estate. After Martha died from complications of childbirth in 1782, Betty Hemings and members of her family cared for Martha’s two young daughters, Patsy and Maria, just as they had cared for Martha after her own mother’s death. A few years later, while Thomas Jefferson was serving in Paris as the American minister to France, Betty’s light-skinned, well-spoken, fourteen-year-old daughter Sally crossed the Atlantic to serve as Patsy’s maid. Sally became Jefferson’s concubine, and together they would have six children, four of whom survived to adulthood.

Though it circumvented Jefferson’s promise to his dying wife not to remarry, his long liaison with Sally Hemings forced him to confront his own tortured and racist feelings about slavery and miscegenation. In his Notes on the State of Virginia he had already asserted that blacks “are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Believing that blacks represented a “different species of the same genus,” he concluded that there should be no mixing of the races. And if slaves were to be emancipated, they should “be removed beyond the reach of mixture” and deported to Africa or the Caribbean. But the racial mixing he abhorred exactly described his relationship with Sally, which resulted in a new family, one that he was unwilling to abandon or to avow.

Despite the persistent interweaving of the Hemings clan with Jefferson and his family, the line between masters and slaves blurred only gradually and incompletely. The southern myth of racial separation and purity was maintained while the reality of consanguinity was secretly acknowledged. Even as the two families colluded in pretending not to know who fathered Sally’s children—or who, for that matter, had fathered Sally—they were bound by unassailable ties.

When Jefferson was elected to the presidency in 1801, his daughter Patsy, now married to Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., brought two of her young children—Ellen and Jeff—to Washington under the care of Priscilla Hemings, the wife of one of Betty Hemings’s sons. Eight years later, when the Jeffersons and the Randolphs were back home in Virginia, Patsy served as the mistress of Monticello, supervising her enslaved half-siblings and helping them learn a trade so that, one distant day, they would be able to support themselves as free people. For the children of Jefferson and Sally Hemings, there was at least that prospect of eventual freedom, which, as one son later said, permitted them to be “measurably happy.”

The Jefferson, Hemings, and Randolph families shared an intricate genealogical tree. They were related both by blood and by proximity—on Saturday nights, Sally’s sons by Jefferson, Beverly and Eston, played the fiddle while their nieces, Patsy’s daughters, danced with wealthy, eligible young men. Names also connected them—all of Sally’s children except for one were named after people in the Jefferson-Randolph clan, and a year after Sally and Thomas Jefferson had a son named Madison, Patsy gave birth to her own son, James Madison Randolph.

In his will, Jefferson freed Madison and Eston. His and Sally’s two other children, their daughter Harriet and son Beverly, fled Monticello before his death. No one pursued them. Harriet, Beverly, and Eston would assimilate into white society, marry into respectable families, and raise children. Madison, who later wrote bitterly that Jefferson “was not in the habit of showing partiality or fatherly affection” to him and his siblings, preferred to identify as black. Jefferson did not free Sally in his will, but she left Monticello anyway and lived with the families of Madison and Eston until her death in 1835.

A year before Jefferson died, Patsy’s daughter Ellen married Joseph Coolidge of Boston. Upon her arrival in Massachusetts, Ellen shared with her grandfather her first impressions of New England. “It is certainly a pleasing sight, this flourishing state of things,” she wrote. “It has given me an idea of prosperity and improvement, such as I fear our Southern States cannot hope for, whilst the canker of slavery eats into their hearts, and diseases the whole body by this ulcer at the core.”

In 1794, a year after her husband John Todd died, Dolley Payne Todd married James Madison. She had grown up in a modest, slave-owning family in Virginia, though her Quaker parents liberated their five slaves while she was in her teens. But when Dolley and her young son Payne Todd moved to Montpelier, Madison’s Virginia estate, where more than a hundred slaves worked, she took to the part of plantation mistress as though she had been born to it. Fully engaged in running her household, she supervised the domestic slaves and even monitored some who toiled outside—field workers and artisans. Not least, like all other plantation mistresses, she was the “keeper of the keys,” a position, Schwartz notes, founded on the premise that slaves would steal anything they could if given the chance. For that infraction, Dolley once resorted to temporarily banishing her maid Sukey from the mansion.

Years later, Madison expressed sympathy for the arduous tasks performed by women like his wife. According to the English writer Harriet Martineau, who visited Montpelier in 1835, the former president said, with an obtuseness that reflected his obeisance to southern mores, that he pitied slave mistresses

even more than their negroes, and that the saddest slavery of all was that of the conscientious Southern women. They cannot trust their slaves in the smallest particulars, and have to superintend the execution of all their own orders.

Whatever burdens her husband thought she was bearing, Dolley’s life was made much easier thanks to slaves. Like Martha Washington, she thought of them not as people capable of thoughts and emotions, but rather as a way by which work could be done for her. When Madison served as secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson, the couple brought more than two dozen slaves to Washington. The lively and fashionable Dolley loved to entertain, and sometimes two hundred guests—occasionally five hundred—attended parties arranged and served by her slaves.

Unlike Washington or Jefferson, James Madison bore few scars of inner conflict over slavery. He neither defended it nor called for its abolition, prudently hoping to avoid such a divisive and incendiary subject. But President Madison’s secretary Edward Coles, appalled by slavery’s relentless cruelty, abandoned Virginia in 1819 for Illinois, freed his slaves there, and gave each head of family 160 acres. On board the barges that carried them all up the Ohio River to Illinois, he told them that they would soon be free. “The effect on them was electrical,” he later wrote. “In breathless silence they stood before me, unable to answer a word, but with countenances beaming with an expression…which no language can describe.”

Coles had repeatedly urged Madison to free his slaves, too—if not for moral reasons then for the sake of his legacy, “to put a proper finish to your life and character,” he counseled in 1832. But even if Madison had wanted to do so, he knew no alternative to the slave economy. Instead, he raised capital by selling sixteen slaves in 1834 and twelve more the following year.

His death in June 1836 left Montpelier in the direst straits. Within a few months, Dolley started selling slaves, ignoring the clause in her husband’s will ordering that no slaves be sold without their consent. In vain her slaves cried and protested. “We are afraid we shall be bought by what are called negro buyers and sent away from our husbands and wives,” wrote one slave, pleading with Dolley to find a local buyer. “Think my dear misstress what our sorrow must be.”

Most of the slaves at Montpelier were sold away from the plantation. Some remained with the new owner, and the rest were retained by Dolley and her son Payne. Dolley sold Sukey, her maid of more than forty years, to a family in Washington for a set term of years, after which she would finally be free. An abolitionist newspaper in upstate New York reported on the sale, noting that “the price was paid” to Mrs. Madison, and that Sukey was now at work “with the prospect of freedom some time.”

Dolley freed just one slave, her husband’s longtime valet, Paul Jennings, but only after he paid $200. Jennings raised $80 and borrowed the rest from Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, eventually paying him back. Ironically, it was only the alcoholic, wastrel Payne Todd who freed his fifteen remaining slaves in his will. His many creditors contested that gift, but the slaves successfully petitioned the estate administrator for their freedom.

James Madison’s slaves couldn’t salvage his finances, and his indebtedness ultimately broke up their families and cast them to the wind. The ties that bound in this case were those of owner and exploitable property in a broken slave economy. Jefferson, too, blamed his slaves for his immense debts, but the ties between his white family and the enslaved Hemings family were deep, intimate, and conflicted.

As for the Washingtons, whereas Martha had a conventional view of the master–slave relationship, her husband recognized that slaves were more than legal property. Indeed, he was truer to Enlightenment values than many of his more philosophically inclined fellow Founders, for he did not deny that slaves, like white people, had inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. George Washington was no radical, and he would not speak publicly against slavery lest he inflame divisions in the young republic, but by his actions and empathy he demonstrated that the ties that should bind us are those of our shared humanity.