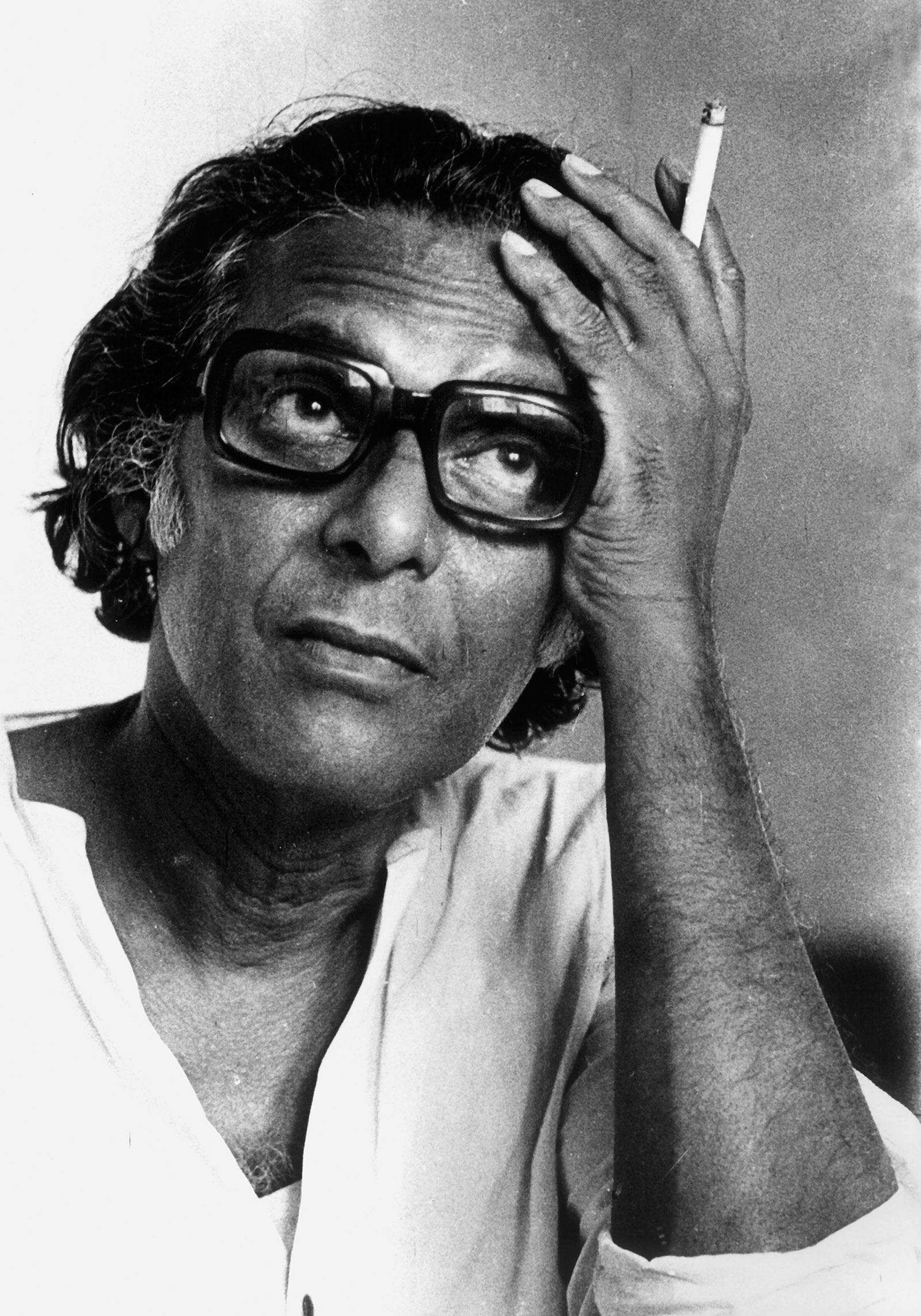

Over almost a century, the Bengali film director Mrinal Sen has witnessed mass famine, the partition of his homeland and the ceding of his birthplace to another country, deadly street battles between Maoist guerrillas and the police, and the rise to power of right-wing nationalists in his traditionally leftist state. Sen responded to historical calamity by cultivating what he called “rough edges,” a rejection of the formal refinement and tonal subtleties of his Calcuttan compatriot and inspiration Satyajit Ray, with whom he frequently sparred in the press. Extending the humanism of Ray’s celebrated Apu Trilogy in more experimental directions, Sen became a seminal figure of India’s “parallel cinema,” which was less the counterpart that its name suggests than an utter refusal of the predominant model of filmmaking in the subcontinent, now colloquially known as Bollywood. Humane, intellectual (but, he claims, not at all erudite), religiously agnostic and politically radical, contradictorily inclined to blunt appraisal and cunning ambiguity, Sen gradually transformed from a polemicist to a poet committed to incertitude. “Life itself is uncertain and inconclusive,” he has said. “Then why should I make a creation conclusive? Thus, all my films are open-ended.”

Now ninety-four, Sen grew up during the era of Gandhi’s protest against colonial rule, in rural Faridpur, “an unknown little town belonging to the ancient landmass of undivided India,” as the director describes it in a rambling but ultimately moving memoir—included in the recently republished collection of his essays and interviews, Montage—that depicts his reluctant return to his birthplace after many decades away. Located in East Bengal at the time of his birth, after the 1947 Partition Faridpur was apportioned to East Pakistan.

Born into a Hindu household teeming with siblings—there were a dozen children in all—Sen imbibed the progressive anti-British nationalism of his father, a lawyer who, risking his own arrest, fearlessly defended patriots, political militants, and others who could not afford legal representation. The capacious though crowded Sen home, which frequently also accommodated relatives of inmates awaiting the death penalty, may well have provided the young Mrinal with the fraught sense of domestic space that he would masterfully employ half a century later in the family dramas of his greatest period of filmmaking.

Following his father’s politics, Sen was first arrested at the age of eight for participating in a protest march—a policeman threatened to beat him to jelly because he was the youngest participant—and remained a Marxist, associated with, though never a card-carrying member of, the powerful Communist Party.* Two years ago, the ailing director, a vehement critic of the right-wing Trinamool Congress recently elected in Bengal, witnessed the cancellation of a retrospective of his films scheduled for the 2016 Kolkata International Film Festival, reportedly due to his ongoing conflict with conservative state officials. This local affront adds to the disregard that Sen’s cinema has suffered in the West since the limited distribution of his masterpiece, The Case Is Closed (Kharij), in the early 1980s. His work urgently deserves reappraisal.

“I came to cinema fairly late,” Sen states in the first entry of Montage, an essay charting what he calls his “uncertain journey” toward his vocation as a filmmaker after training in physics at the Scottish Church College and working as a traveling medicine salesman. In one of many disarming anecdotes, Sen recounts that on his last night at home before decamping from Faridpur for Calcutta,

Making certain that my father was within earshot, I asked my mother, “Ma, have you ever noticed any exceptional quality in me? You know…like great personalities display in their childhood? Any flash of genius?”

That flash was scarcely apparent in Sen’s first films, made after he encountered Rudolf Arnheim’s Film as Art at the Imperial Library, a theoretical treatise on the aesthetics of cinema that inspired him to enter the film industry, first as a sound technician, then as a director. The sometimes caustically self-critical Sen prefers that his debut film, Night’s End (Ratbhore), never be shown, so appalled is he by its ineptitude, and dismisses the follow-up, Under the Blue Sky (Nil Akasher Niche), on the first page of Montage as “over-sentimental, technically poor, visually unsatisfying,” although he adds that “its political thesis which upholds the notion that the struggle for Independence is inseparably linked to the liberal world’s crusade against fascism and imperialism” did win the admiration of Jawaharlal Nehru.

Sen grants that his third film, Wedding Day (Baishey Sravan), “made me feel great. It wasn’t really a great film, but I felt good nevertheless.” In its entropic emphasis on crumbling architecture, its intensive spatial constraint—“the camera remains indoors…and moves outside only once,” the director claims—and its oblique treatment of the 1943 Bengal famine, which eventually destroys the already deteriorating relationship between a man and the much younger bride his widowed mother chose for him, Wedding Day became a kind of formal and thematic template for Sen’s subsequent cinema. Caused in part by British colonial policy, the famine killed millions, leaving the streets of Calcutta strewn with the dead and dying, and would recur in Sen’s films, both as actuality and metaphor.

Advertisement

In Wedding Day, it intrudes inexorably upon the confines of a young couple’s rural home, eventually driving the desperate bride to suicide. But it is never directly shown; the audience is left to infer the famine from an accretion of narrative details. Similarly, in a stroke of early mastery, Sen registers the woman’s demise with a shot of the rod she has used to hang herself, still swinging as the husband bursts in to discover her dead. Sen’s use of one image as a metonym for another recalls the work of Robert Bresson, a director he greatly admires; Sen would also later adopt Bresson’s technique of letting the sound from a subsequent sequence begin early, over the previous shot.

“Understandably, such a film can hardly be a financial success,” Sen writes with characteristic understatement. Still, Wedding Day gave the director not only what he calls “a firm foothold in the world of cinema,” but also a new credo:

And, for reasons of my own, I henceforth made it a point to constantly break new ground, cast off the shackles of conformism and evolve new modes of expression. Risky propositions all, very risky. Even now. In every sphere, in any discipline.

That welter of dead phrasing and mixed metaphor indicates much about Sen’s writing. His reliance on the passive voice—“tables were thumped emphatically”—renders an account of an accidental explosion on the set of Genesis less harrowing than wearisome, and his attempt at epistrophe in a tribute to fellow Bengali auteur Ritwik Ghatak aims to resonate but instead exasperates:

Comatose Ritwik, larger-than-life Ritwik, reckless Ritwik, heartless Ritwik, indisciplined Ritwik…. The same larger-than-life Ritwik, reckless Ritwik, heartless Ritwik, indisciplined Ritwik.

Ironically, Sen’s dedication to aesthetic innovation led to his first popular hit, Bhuvan Shome, a sweet-natured satire in which the eponymous bureaucrat—an aging railroad employee so rigid in his rectitude that he fires his own son for laziness—learns from a young peasant woman whom he encounters on a bird-hunting expedition in Gujarat that trust, camaraderie, and even a little dishonesty make life more bearable. The director Shyam Benegal claims that Bhuvan Shome, which is widely considered the pioneering work of the Indian New Wave (or “parallel cinema”), was as important to the development of Indian cinema as Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, the first work in his Apu Trilogy, made more than a decade earlier.

An avid cinephile, Sen had been greatly affected by François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Jules and Jim, which he saw in 1965. The French director’s influence is readily evident in the fusillade of New Wave devices that Sen employs in Bhuvan Shome, including a rapid montage of actualités at the start of the film (images of fellow Bengalis Satyajit Ray and Ravi Shankar, shots of street protests in Calcutta); a profusion of freeze frames clearly modeled on the famous one that concludes The 400 Blows; and a startling play with image masking, an archaic technique that Truffaut had revived in Jules and Jim. Sen will, for instance, suddenly freeze on a widescreen close-up of Shome chomping a cigar and mask the top and bottom of the image, leaving a constricted, mail-slot-like frame that conveys the narrowness of the bureaucrat’s purview.

The broad comedy of Bhuvan Shome maintains traces of Bollywood’s confectionary style that Sen so adamantly rejects. (I “cultivate a fierce loathing towards our vapid indigenous films,” he writes, claiming they have “nothing to do with art or Indian reality.”) But the film’s aural and visual experiments and unfettered, sometimes improvised plot were sharp departures from Bollywood’s garish romantic-musical conventions. Sen jettisoned the tripod on which his cinematographer relied and blithely interpolated animation (a flock of hand-drawn birds circles Shome’s head as he studies his “shooter’s bibles” to prepare for the bird hunt), swish pans, point-of-view shots, blackouts, and a stuttering montage of repeated zooms into a photograph intercut with shots of a train. (Sen’s dilatory traveling shots, in which the camera fastens on the turning wheel of Shome’s carriage or follows the leisurely advance of a bullock cart, anticipate similar attenuations of transport in the modernist cinema of Manoel de Oliveira.) Sen also innovated on the soundtrack, which included extraneous bursts of tabla and sitar, electronic distortion, and sudden silences.

One of Sen’s major achievements, the so-called Calcutta Trilogy, which portrayed the director’s beloved city during the clashes between Maoist Naxalites and the police that broke out there in 1970, was made in the spirit of “madness and…freshness” that the director found in the French New Wave. Here, however, Sen traded Truffaut’s lyricism for the militancy of Jean-Luc Godard, who emerged from the riots of May 1968 newly radicalized and dedicated to a new, collectivist Marxist cinema. Sen too remade himself as an artist:

Advertisement

I went wild. I released everything that was maddening, restless, nervous, vibrant, buoyant, and even flippant within me in a desperate bid to break the frontiers created and closely guarded by the conservatives.

In Interview, the first film in the trilogy, Ranjit Mallick made his first screen appearance as a hapless young man searching for a suit to wear to a job interview for a British company in a city gone on strike. The fourth wall is demolished in a sequence on a crowded tram, when a bystander recognizes the young man from a photograph in a magazine. In his biography of Sen, Deepankar Mukhopadhyay cites this sequence as the first use of Brechtian alienation in Indian cinema, although Sen denies Brecht as an influence. (Never mind that one can find far earlier Brechtianisms in Ray’s The World of Apu.) “I am not a star, not at all!” Mullick insists, addressing us directly, as Jean-Pierre Léaud does in Godard’s La Chinoise just before the cinematographer Raoul Coutard is revealed with his camera—a move Sen replicates here, showing Interview’s cinematographer with his hand-held apparatus.

Sen frequently used nonactors and, again like Godard, incorporated details of their lives into their screen personae. The actor continues his monologue:

My name is Ranjit Mullick, I live in Bhawanipur, and work for a weekly magazine. I go to the press, correct the proof and do other tasks. I have a very uneventful life, you know? Yet that is precisely what attracted Mrinal Sen…. Yes, yes, the filmmaker, you know?

An awestruck passenger peering directly into the viewfinder cries, “Wow, is this what you call cinema?” Later in the film, a jump cut suddenly equips Mullick’s hand with a stone to throw through a shop window, at which point Sen unleashes a torrent of documentary footage: street protesters, the Vietnam War, bombs exploding.

Sen would refine what he later called Interview’s “infantile enthusiasm” in the subsequent films in the trilogy: Calcutta 71, a set of linked stories depicting the city over four decades, from the famine to the Naxalite era; and Padatik, the portrait of a fugitive activist who escapes the police and takes shelter with a young woman. But he remained a stranger to subtlety. “I am not ashamed of being a pamphleteer if it makes a point,” he later declared. In Calcutta 71 he crudely juxtaposes a scene of a boozed-up bourgeois smugly declaring at a posh cocktail party that “a new India is being born” with a shot of squalling babies in a Calcutta slum, and lets the screen proliferate with the word “despair” in a Godardian intertitle.

“When I use the word ‘blatant,’ I mean it and write it in a positive sense,” Sen declares defiantly in Montage. (Calcutta 71 became a local hit partly because its documentary footage of street riots offered final glimpses of students shot dead to their grieving friends and relatives.) Padatik, however, revealed a more eloquent stylist in long takes that required complex navigation of interior space; at one point, a young Punjabi woman recounts her family’s troubled past in a shot that lasts over two unedited minutes as it sinuously moves between characters and various areas.

“With age and experience,” Sen observes, “I am becoming more careful, more austere.” In this shift, the pattern of Sen’s career turned out to be the obverse of that of Ray, to whom Sen pays slyly diffident tribute here in a chapter titled “Apu, Eternal Apu.” While Ray’s style ultimately stiffened into didacticism and artifice, Sen’s freed itself of invective and became increasingly restrained. In a television interview not included in Montage, Sen claims that Ray, who later made his own stingingly critical Calcutta Trilogy set in the Naxalite period, enjoyed only a single decade of greatness, from 1955 to 1965—“ten years of a master,” in Sen’s backhanded assessment, perhaps payback for Ray’s mocking the plot of Bhuvan Shome as “big bad bureaucrat reformed by rustic belle.” Sen felt “uncomfortable” and “let down” by Ray’s cinema, especially in his last three films, which give a harsh estimation of greed and intolerance in contemporary India. That the widely venerated Ray made this studio-bound, admonitory trilogy after a five-year hiatus enforced by a severe heart attack, and died soon after their completion, adds a splash of acid to Sen’s criticisms.

Sen claims that Ray’s fault lay in moving away from interiority to “exterior reality,” a transformation that proved the opposite of his own. In the first chapter of Montage, he writes that his 1979 film And Quiet Rolls the Day (Ek Din Pratidin), in which a family spends a night anxiously awaiting the return from work of the eldest daughter, their only breadwinner,

marked the beginning of a new phase in my career as a filmmaker…. I am always trying to delve into the interior, into that realm which lies behind the façade of the outside world; to discover mysteries, frustrations, confusions, contradictions.

Sen experienced his own “ten years of a master” in the decade from And Quiet Rolls the Day in 1979 to Suddenly One Day (Ekdin Achanak) in 1989. (The repetition of “Ek Din” in their respective Bengali titles, meaning “one day,” augments this sense of bookended symmetry.) He moved in these films from the streets of Calcutta to the dilapidated interiors of urban middle-class homes and once-palatial rural ruins. The cinema that resulted from this alteration bore more than a little resemblance to the Chekhovian tales of Ray’s middle period.

There are striking similarities between Sen’s The Ruins (Khandahar), in which three young men from Calcutta go on a weekend outing to a depopulated village, and Ray’s Days and Nights in the Forest, in which four Calcutta careerists make a similar journey. In both films, the outing begins as a lark and gradually darkens, the urban intruders seemingly insensible to the tensions they create amid the ruins and the forest. As highly literary as Ray, Sen based many of his films on Bengali stories and novels, though he avoided adapting the best-known local author (and not coincidentally, Ray’s favorite), the legendary Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore, because Sen always changed his source material—“Is it obligatory on my part to treat the text as a fragile artifact, preserved in a glass case in some museum?” he asks in Montage—and worried that Tagore’s followers would vociferously object to any such revisions.

Sen transformed his visual style from the skittish “try anything” experiments of his political films to something more elegant and implicative. The supple tracking shots that navigate the crumbling urban abodes in his late films—Sen renamed them “trolley shots” after the primitive means he used to achieve them—are artfully deployed in the largely outdoor rural settings of The Ruins, In Search of Famine (Akaler Sandhane), and Genesis, in which he uses the camera to section off sprawling open-air ruins into smaller, discreet zones. The spatial relations in these later Sen films reflect alliances and ruptures within the households they depict. The balcony in Suddenly One Day becomes the lonely redoubt of an increasingly estranged father as he contemplates his many failures. In The Case Is Closed, a servant boy’s choice to move from his assigned sleeping space under the stairs into the kitchen for one night of warmth proves fatal, precipitating a moral crisis for his oblivious masters.

Perhaps imposing order retroactively, Sen pronounced that three of his ambiguous, calculatedly inconclusive family dramas—And Quiet Rolls the Day, The Ruins, and Suddenly One Day—comprise “the absence trilogy.” The theme of absence certainly structures the flanking films, both set in Calcutta. In the later one, another apprehensive clan awaits the homecoming of their patriarch, a retired academic who “suddenly one day” in the midst of monsoon season disappears from the family flat and never comes back.

The Ruins treats absence more obliquely in its account of a young woman tending to her blind, bedridden mother—magnificently played by the director’s wife and frequent star Geeta Sen—and their once-grand, now decrepit rural home. The missing person in this case is a man who promised to wed the daughter but who left for the city long ago and married someone else. The delirious mother nurses the belief that he will return to carry out his promise, and that one of the trio of male visitors from Calcutta is this very man. One wonders if Sen was aware of the similarities between this plot and that of the Dostoevsky tale that served as the source for Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer (Quatre nuits d’un rêveur), to which Sen dedicates part of the final chapter of Montage.

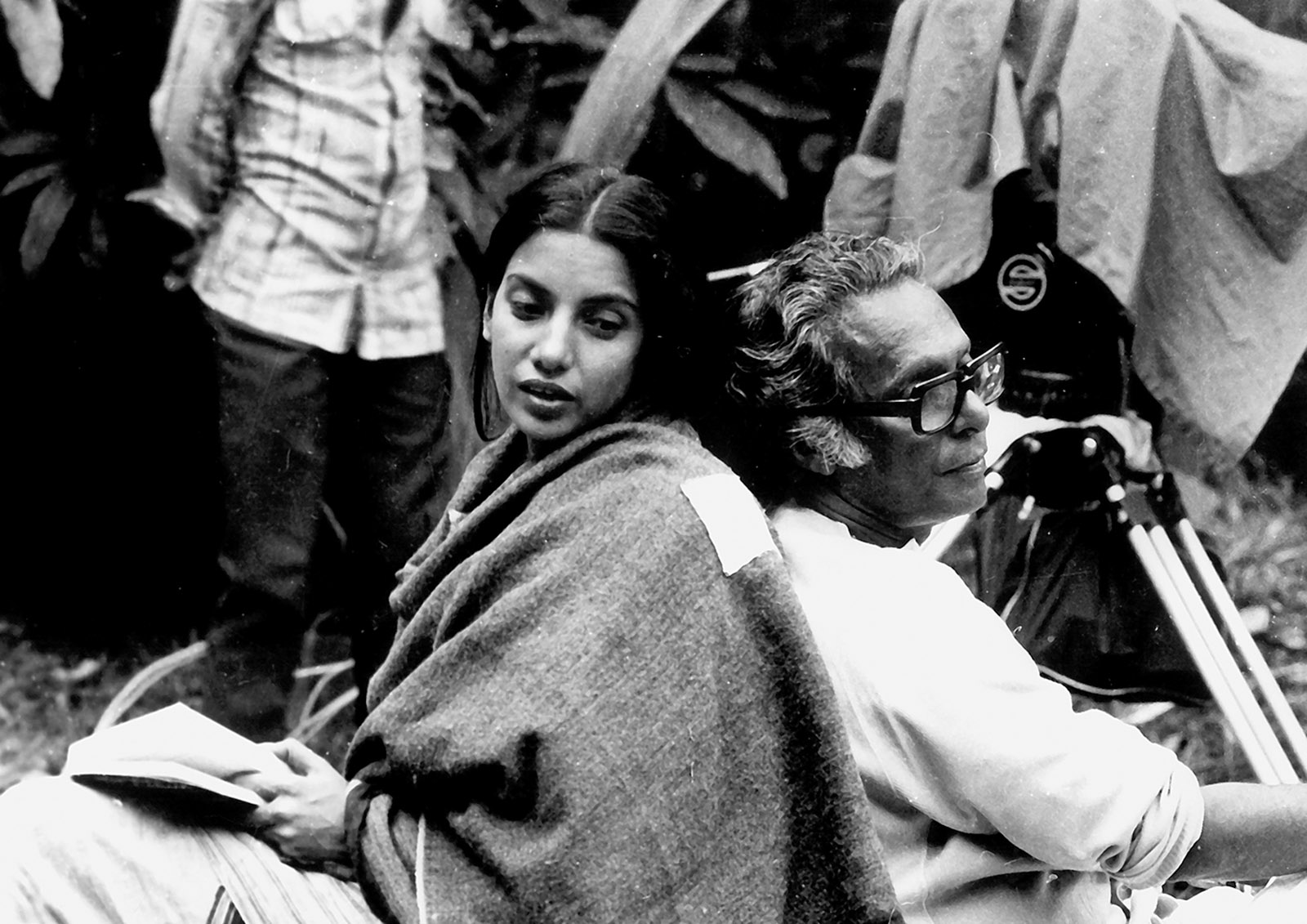

Affectionately known as Mrinal-da by his actors, crew, and family members, all of whom seem to adore him, Sen has always praised and encouraged his stars and technicians, even while patiently ordering retakes necessitated by their errors. (They would accept much lower remuneration for the honor of working with him.) But his generosity has not always extended to other directors—he implies here that Michelangelo Antonioni is a fallen master and accuses the prominent Algerian auteur Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina of dishonesty and impotence—or to himself. Sen dismissed the Marxist allegory of his late film Genesis as “crap.”

In The Ruins and In Search of Famine, he offered a kind of self-excoriation: the first centers on a photographer (in the original short story he had been an angler), the second on a film director making a movie about the 1943 Bengal famine. Both artists, easily read as self-portraits, appear unaware of the arrogance with which they intrude into destitute villages to capture images of decay and suffering and the ease with which they abandon their miserable subjects to return to comfortable lives in the city.

“I am a filmmaker by accident and an author by compulsion,” Sen once claimed. His graphomania has resulted in a book that is erratically edited, repetitious, and littered with stylistic and factual gaffes. The auteur who allowed accident into his artistry might remain untroubled by the many mistakes he makes in Montage. Sen misrepresents Lev Kuleshov’s famous experiment in filmic perception; misspells the names of directors (Stork, Gleizer), curators (Tom Ladi), and characters (Iogor); misnames movies (The Stalker) and misconstrues important details in describing several films, including the final sequence of Antonioni’s La Notte.

Locale can baffle him; Sen misidentifies the city in which István Szabó’s Sweet Emma, Dear Böbe takes place and incorrectly asserts that Four Nights of a Dreamer begins as “a young woman is about to commit suicide by jumping from the rooftop.” Rather, she is poised to leap from the Pont Neuf in Paris, a crucial setting in this Seine-side nocturne. But it would be churlish to dwell on such minor lapses from the munificent Mrinal-da, who reinvented his self and his art so persistently that he called his autobiography Always Being Born.

This Issue

May 24, 2018

Crooked Trump?

Freudian Noir

Big Brother Goes Digital

-

*

For an account of his arrest, see John W. Hood, Chasing the Truth: The Films of Mrinal Sen (Seagull, 1993), p. 6. ↩