Halfway through Monastery, its narrator, a writer and teacher of literature named Eduardo Halfon, is en route from his native Guatemala to Belize, where he has been invited to give a reading at a university. After a tense encounter with a thuggish border official—Halfon’s Guatemalan passport has expired, but he has a valid Spanish one—the battery in his borrowed car dies. Waiting for it to be repaired, he goes into a small restaurant where there is an enormous red macaw and orders a beer from the waitress, a young girl with a baby strapped to her back. A joyfully guiltless smoker, he is enjoying his beer and cigarette when the border official walks in. The guard pulls the waitress onto his lap, “his long-nailed hand holding her neck, like a hook,” while ordering pork carnitas and cracklings.

Halfon thinks—as he often does—about his Polish grandfather, a survivor of Sachsenhausen and Auschwitz, who used to tell him that the numbers tattooed on his arm were to remind him of his phone number. The border guard is wearing a ring that reminds Halfon of the one his grandfather had bought in 1945 and worn “for the rest of his life, for the next sixty years, on his right pinkie finger, as a way of mourning for his parents and siblings and friends and all the others exterminated by the Nazis in the ghettos and concentration camps.”

The passage that follows (and concludes this scene) exemplifies the themes and method of the three of Halfon’s fourteen books thus far translated into English—The Polish Boxer (2012), Monastery (2014), and, most recently, Mourning (2018)—all of which seem like parts of a single fictional project with recurring characters, details, settings, and preoccupations, and all narrated by “Eduardo Halfon.” Among these preoccupations (obsessions, really) are the legacy of violence and mass murder in Europe and Latin America; the frequency and facility with which the past intrudes upon the present; the quixotic effort to separate family myth from historical fact; and the ways in which pleasure—food, love, sex, humor, cigarettes, beer, the beauty of nature, and the surprises offered by travel—consoles us.

The section about Halfon’s encounter with the border guard typifies his style: simple declarative sentences punctuated by flights of rhetorical, incantatory lyricism. Halfon is so struck by the resemblance between the guard’s ring and that of his grandfather that he wonders if it was “exactly the same” one:

Or at least it was all exactly like the ring in my memory, the ring as I recalled it or as I wanted to recall it, on my grandfather’s pale and slightly crooked right pinkie finger. And although I knew it was impossible, even preposterous, even absurd, I couldn’t help imagining that this ring, on this greasy hand, was indeed my grandfather’s ring with the black stone. Not a similar one. Not an exact replica. But the same one…. The one that, when he died, was inherited by one of my mother’s brothers. The one that had been stolen from a safe one night by a thief who never knew what he was stealing; by a thief who never knew that in that insignificant and somber black stone, one could still see the perfect reflections of my grandfather’s exterminated parents (Samuel and Masha), and the faces of my grandfather’s exterminated sisters (Ula and Rushka), and the face of my grandfather’s exterminated brother (Zalman), and the faces of so many exterminated men and women and boys and girls and babies who were killed as they slept in the arms of their mothers, as they dreamed in the gas chambers; by a thief who never knew that in that small black stone it was still possible to hear the murmur of all these voices, of so many voices, intoning in chorus the prayer for the dead.

The macaw shrieked and stretched out its wings and, still on its perch, started to flap them energetically, desperately, as if wanting to fly.

The truth about his Polish grandfather—who claimed to have been rescued from death in Auschwitz by the sage advice of a Polish boxer, and at other times was said to have been saved by his own carpentry skills—is only one of the mysteries that Halfon (the character and perhaps the author) is attempting to solve. But one hesitates to identify the author too closely with his eponymous hero, who early on in The Polish Boxer warns us:

A story is nothing but a lie. An illusion. And that illusion only works if we trust in it. The same way a magic trick impresses us even though we know perfectly well that it’s a trick. The rabbit doesn’t actually disappear. The woman hasn’t actually been sawed in half. But we believe it. The illusion is real, oxymoronically.

This passage occurs in a chapter about Halfon’s efforts to teach Maupaussant, Poe, and Flannery O’Connor to entitled Guatemalan university students with no interest in literature. When his only talented pupil—a gifted poet and devoted reader of Rimbaud, Pessoa, and Rilke—drops out of school and returns home to the highlands, Halfon drives into the hills to find out why he left, a journey that inspires a meditation on place names that compresses, into a few sentences, three of Halfon’s recurrent concerns—the beauty of language, the complexities of what it means to be Guatemalan, and the enduring legacy of historical violence:

Advertisement

Guatemalan place names never cease to amaze me. They can be like gentle waterfalls, or beautiful cats purring erotically, or itinerant jokes…. I suppose Guatemalan place names are the same as Guatemalans, when it comes down to it: a mix of delicate indigenous breezes and coarse Spanish phrases used by equally coarse conquistadors whose draconian imperialism is imposed in a ludicrous, brutal way.

When Halfon finds his former student on the farm his family works but doesn’t own, and which the young man must now take over from his father, who has died, Halfon is reminded of the harsh lives of most Guatemalans, people who rarely wind up in his literature class. Meanwhile the student offers his former teacher a lesson about language and poetry:

Do you know, Halfon, how to say poetry in Cakchikel? Juan asked suddenly. And I said no, I had no idea. Pach’un tzij, he said. Pach’un tzij, I repeated. And I savored the word for a time, taking pleasure in it purely for its sound, for the delectable lure of its pronunciation. Pach’un tzij, I said once more. Do you know what it means, he asked, and although I hesitated, I said no, but that it didn’t really matter. Braid of words, he said. It’s a neologism that means braid of words, he said. Pach’un tzij, he intoned, giving it an elegance that could only be gained through unskeptical spirituality. It’s something like an embroidered blouse of words, like a huipil of words, he said, and that was all.

Many of the chapters in Halfon’s books center around journeys, travel for pleasure and work, travel for all the reasons that make immigrants leave home. In the second half of Mourning, Halfon tells his family story: his Lebanese grandfather emigrated to Guatemala via Corsica, his Polish grandfather from Łódź via Auschwitz. Like his narrator, Halfon left Guatemala with his family in 1981 as a boy of ten, fleeing the long civil war that resulted in the genocidal massacre of indigenous Guatemalans. They moved to southern Florida, and Halfon—a gifted math student with no interest in fiction—studied engineering in North Carolina. In a piece for The Guardian, he described returning to Guatemala in 1993, knowing little about the country and speaking only passable Spanish. He worked for his father’s construction company for five years before deciding to study philosophy at a local university, where he discovered literature and became first a teacher and then a writer. When his first novel was published in Guatemala in 2003, he received a threatening phone call and a disturbing visit; the Salvadoran writer Horacio Castellanos Moya advised him to leave the country. Halfon currently lives in Nebraska.

Mourning, eloquently translated by Lisa Dillman and Daniel Hahn, is framed by the story of Halfon’s attempts to find out what happened to his father’s mysterious older brother Salomón, who allegedly drowned in Lake Amatitlán at the age of five. When Halfon visits the lake house where he went as a child, he asks an old woman named Doña Ermelinda about his uncle. What follows is a list, or litany, of boys (not named Salomón) who drowned in the lake.

Each of the old woman’s stories begins with the phrase “Another drowned boy was also not named Salomón,” and goes on to tell about a boy who fell into the water while searching for a lost oar, and whose half-naked ghost is still said to haunt the shore of the lake; a young man killed by soldiers because his father had been preaching sermons on social justice; a boy who drowned during an aquatic religious procession; a boy who disappeared while jumping from a rock at a castle whose cellar was once used as a torture chamber for a dictator’s enemies and prisoners. But the truth about Eduardo’s uncle involves only exile and pain: Salomón was a desperately ill child who died far from home, alone, in a clinic to which his mother had taken him in the hope of alleviating the suffering that had afflicted him since birth.

Advertisement

In Mourning, Halfon travels to southern Italy to participate in a Holocaust memorial at a site where the original concentration camp has been knocked down and replaced by a replica, “a kind of mock-up or sample or theme park dedicated to human suffering.” And he uses a Guggenheim grant to get to Łódź, where his grandfather lived before he was sent to the camps, and where Halfon considers telling his hostess why he is wearing the pink overcoat to which he has alluded in the earlier novels:

I was going to tell her that, also in Warsaw, I’d had to buy my ridiculous pink coat in a secondhand shop at the Centrum metro station, under Defilad Square, because the airline had lost my suitcase, and that by the time they finally brought it to my hotel, a few days later, the coat had become a part of me, and I had become a part of it, and my walk was now a Polish woman’s walk. I was going to tell her that later, after much indecision, I’d taken a train to Auschwitz and, dressed in my pink coat, in my Polish woman disguise, I’d paraded through Auschwitz with all the other tourists.

At the end of each journey, what Halfon finds is something other than what he set out to discover. In the Łódź apartment to which he has gone in search of information about his grandfather’s life before the war, he learns instead about the lurid past of the apartment’s current occupant. In Calabria for the ceremony honoring Italian Jews murdered by the Nazis, he meets a young woman named Marina, whose grandfather, an Italian soldier, also spent time in a concentration camp; together Eduardo and Marina discover how effectively alcohol and the promise of romance can blunt the pain of remembrance.

The longest section of The Polish Boxer (for this book Dillman and Hahn are joined by the translators Ollie Brock, Thomas Bunstead, and Anne McLean) describes yet another journey, an odyssey through Belgrade in search of a pianist whom Halfon met in Antigua and who has been sending him postcards from around the world, a musician who seems as peripatetic as Halfon, and who may or may not be a gypsy lost in Serbia. The lengths to which Halfon goes to find his friend turns the chapter into a Borgesian, post-Communist-era, comic detective noir.

Throughout the novels, events are retold, often involving characters who seem different in different settings. One such incident involves Halfon’s meeting the attractive Tamara in a Scottish bar in Antigua. Their initial encounter is evoked when, this time in Tel Aviv, he again sees Tamara, transformed from an Israeli backpacker into a Lufthansa flight attendant. Their romance provides an occasion for Halfon to reflect on his feelings about being Jewish, a subject that reappears, in the background or foreground, of all three novels. In the Scottish bar, Tamara and her friend Yael are surprised when Halfon shows off his limited Hebrew:

I really remembered only three or four words and a random prayer or two and maybe how to count to ten. Fifteen, if I really tried. I live in the capital, I told her in Spanish, to show that I wasn’t an American, and she admitted that she was confused because she hadn’t imagined there were any Jewish Guatemalans. I’m not Jewish any more, I said, smiling at her, I retired. What do you mean you’re not? That’s impossible, she yelled in that way Israelis have of yelling.

Halfon says something similar to a murderously nationalistic Israeli cab driver:

Suddenly he shouted in acceptable English, asking where I was from. Guatemala, I told him. I don’t know if he didn’t hear or didn’t understand or didn’t care. But Jewish? he shouted, almost insolently. I smiled and said: Sometimes. What do you mean, sometimes? his eyes squinting, his question abusive, his voice abrasive and obstructed, as though he were talking with a mouthful of grapes.

Halfon is in Tel Aviv, at the mercy of the cab driver, because his sister has decided to marry into an ultra-Orthodox community: another chance for Halfon to consider what it means to be “sometimes” Jewish—a retired Jew. At the Wailing Wall, he has two different reactions that define a particular strain of religious ambivalence. On his first approach to the wall, “I reached out inconspicuously, cautiously, as though I were doing something forbidden, and I touched it. I wanted to feel something, anything. All I felt was stone.” But as he’s leaving, an impulsive gesture suggests that his response was less neutral than he’d thought:

I was about to leave the Wailing Wall, when I saw on the ground, under my foot, a dirty white slip of folded paper. I crouched down, picked it up, brushed it off, and unfolded it. It was in Hebrew. It was a single sentence, short, black, written in Hebrew letters. I recognized two or three. I remembered how pointless my Hebrew classes had been as a boy—just memorizing the sounds of vowels and consonants—before I turned thirteen. It occurred to me that it was probably someone’s prayer, and that it had also probably fallen from a crack in the wall. I folded it back up. And I don’t know why, but moving quickly, almost fleeing, almost running away from something or someone, I slipped it into my pants pocket.

The epigraph to Monastery (“A cage went in search of a bird”) comes from Kafka, and at moments one senses Kafka’s ghost, along with Bolaño’s, lingering in the shadows. The well-known quote from Kafka—“What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe”—may cross the reader’s mind. Though Halfon’s narrator does little grateful breathing in corners—he’s too busy traveling—there is something Kafkaesque in his hesitation about feeling or declaring that he is Jewish, a reticence that seems more about the impossibility of belonging than the improbability of belief.

Guatemalan, Jewish, Lebanese, Polish, American—the narrator is a composite of identities; he comes from a range of places and doesn’t quite belong anywhere. A running joke (or sort of a joke) in the novels is that he keeps meeting people who can’t pronounce his name. The student poet gives it a peculiar stress. The director of the Italian Holocaust remembrance event introduces him as Signor Hoffman; later that day, Halfon learns that the actor Philip Seymour Hoffman has just died in New York. This information inspires a feat of literary acrobatics, in which Halfon’s imagination ranges rather dramatically from the factual and specific to the improbable and abstract:

Hoffman, Panebianco had called me, while Hoffman died. As though it were more than a slip, more than a coincidence. As though in dying he had liberated his name to float freely around the world, for anyone else in the world to be able to catch it in the air, and say it, and embody it. As though the names of dead artists were butterflies. As though this was what always happened to men who, in their lives and in their art, gave voice to everyman, to all men. As though all of us men, at that exact moment, were named Hoffman.

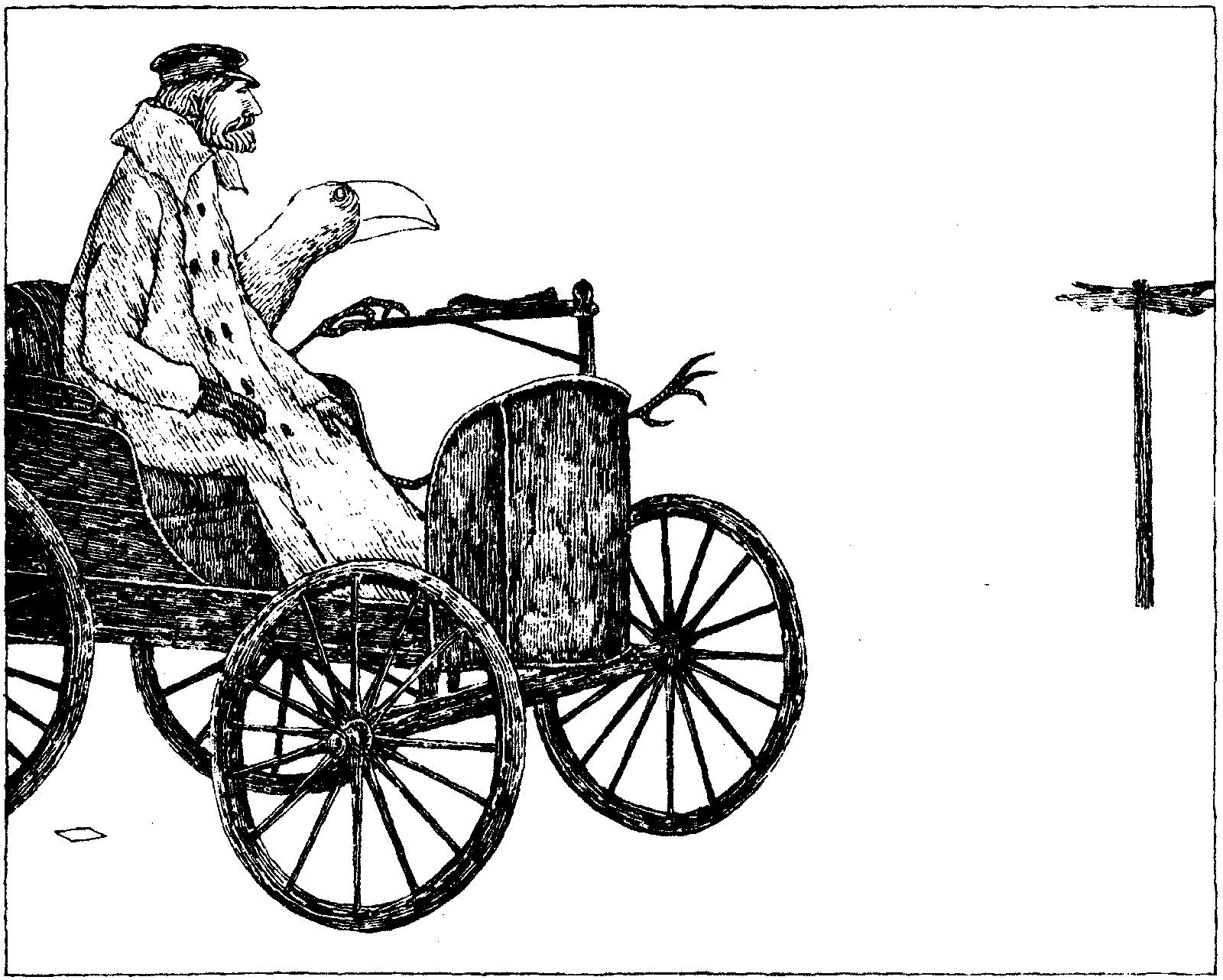

What’s most surprising is that these books, which take on such dark subjects, are so enjoyable to read. I suppose it’s because they’re often funny, and very well translated. Or perhaps it’s because Halfon (the narrator and the writer) is at once so ruminative and meticulously observant. Halfon enjoys telling stories, and does so in a tone that can shift, within a few paragraphs, from casually charming to elegiac. Or perhaps the reason these books stay with us is that they suggest that novels, like life, don’t really have endings, or points. At the end of one chapter, Halfon compares writing to trying to remember something said in a dream: “As we write, we know that there is something very important to be said about reality, that we have this something within reach, just there, so close, on the tip of our tongue, and that we mustn’t forget it. But always, without fail, we do.” Like consciousness, literature keeps tracking back to what can’t be forgotten, to the images that writers can’t get out of their minds: tattooed numbers on an old man’s arm, an absurd pink overcoat, an enormous red macaw.

This Issue

November 22, 2018

A Very Grim Forecast

Romanticism’s Unruly Hero

The Crash That Failed