“At what precise moment had Perú fucked itself up?” (“En qué momento se había jodido el Perú?”) That is the question that Zavalita, the protagonist of Mario Vargas Llosa’s Conversation in the Cathedral (1969), asks himself at the beginning of the novel. By using the verb joderse, Vargas Llosa is implying that something has been aborted or ruined in his country, with the passive voice se underscoring that the fuckup cannot be attributed to one person or incident but that everyone, including Zavalita—who has made a mess of his life—is responsible.1 Though the question referred to the years of the Manuel Odría dictatorship in Peru (1950–1956), it was to resonate across Latin America for writers and readers anxious to pinpoint the moment when everything had gone wrong in their own frustrated nations.

For Gabriel García Márquez, according to his memoir Living to Tell the Tale (2002), there was no doubt about when Colombia had descended into hell, on which particular day “the history of the country split in half.” On April 9, 1948, the future Nobel laureate was placidly eating lunch at his boardinghouse in Bogotá when, a bit past noon, he was interrupted by a breathless friend with the news that Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, the charismatic liberal politician and likely winner in the upcoming presidential elections, had just been killed. Significantly, the friend added, “Se jodió este país”—this country is fucked. Those bitter, biting words—anticipating what, twenty-one years later, Vargas Llosa would write about a different country—turned out to be prescient.

The immediate result of Gaitán’s murder was El Bogotazo—riots, looting, and burning that left the capital smoldering and thousands dead, most of them massacred by army troops.2 The long-term consequences were even worse: Gaitán’s death led to a decade of bloody civil strife known as La Violencia, with a death toll of at least 200,000, and then, eventually, to guerrilla insurrections and death squads, the narcos with their bombs and kidnappings, and the slaughter by sicarios, or hitmen, of many of the land’s most prominent leaders.

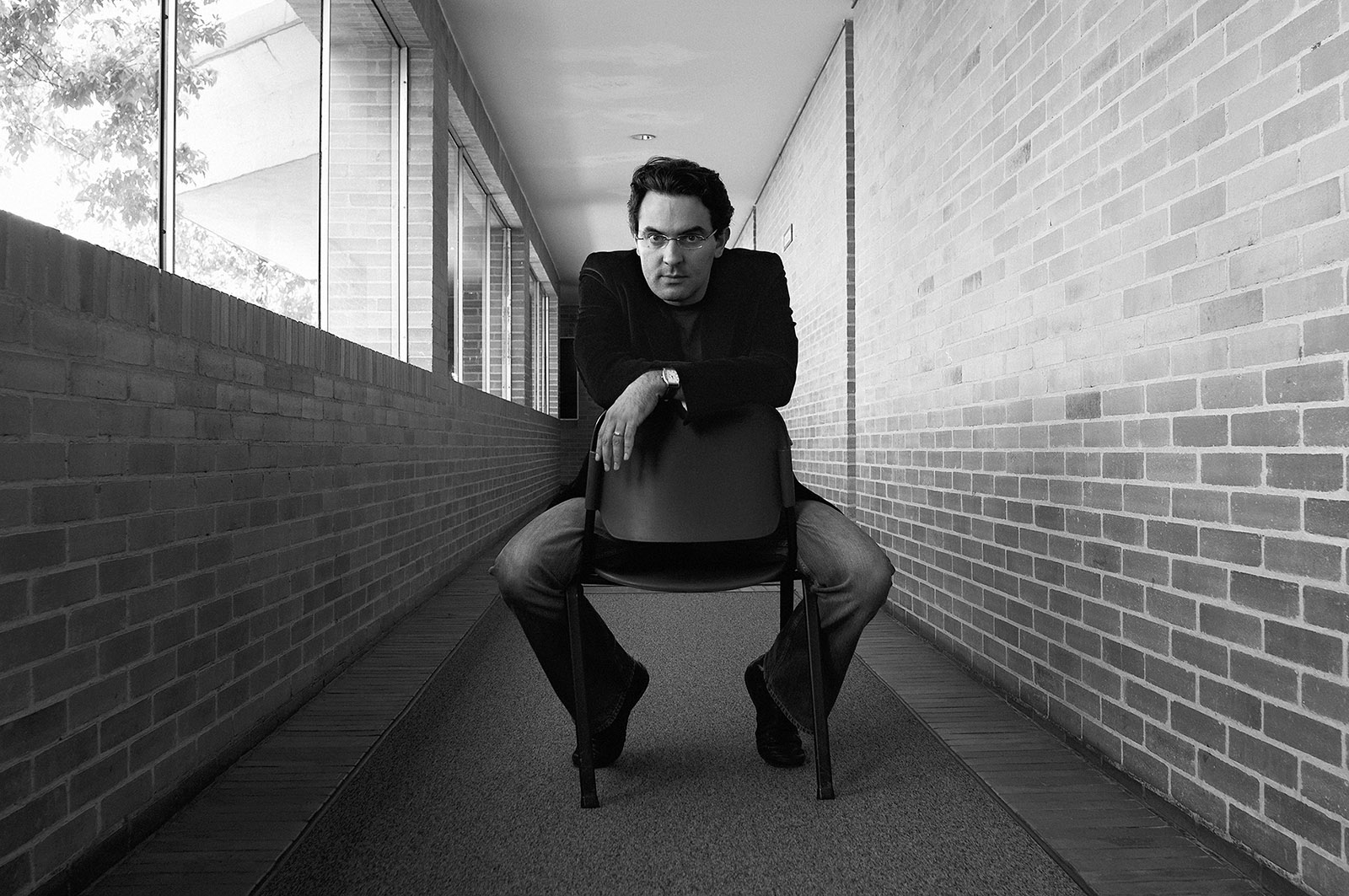

Juan Gabriel Vásquez, who, it could be argued, has succeeded García Márquez as the literary grandmaster of Colombia, a country that can boast of many eminent authors, grew up in the world created by Gaitán’s assassination and returns to it frequently in his monumental novel The Shape of the Ruins (2015), now available in a fluid and faithful translation by Anne McLean.3 “If Gaitán had not been killed,” its narrator asks, “how many anonymous deaths might we have been spared? What sort of country would we have today?” Like his fellow Colombians, the speaker of these words has found himself caught up in an interminable cycle of violence that he does not control and that he fears his progeny will inherit. Unless, that is, he finds a way of understanding what really happened on that fateful afternoon when “my country’s history had been overturned.”

The problem is that Gaitán’s murder is shrouded in mystery. Eyewitnesses offered contrasting accounts. The supposedly demented assassin, Juan Roa Sierra, was almost instantly torn to pieces by an irate mob, making it impossible to know if he acted alone, as the official version would have it, or if he was part of a vast conspiracy, as most Colombians continue to believe, encouraged by none other than García Márquez, who notes in his memoir the presence of a mysterious and elegant man who incited the crowd to kill Roa and then urged them on a rampage, only to disappear into a waiting car, never to be seen again. “It occurred to me,” García Márquez writes, in a passage quoted several times in The Shape of the Ruins, “that the man had managed to have a false assassin killed in order to protect the identity of the real one.”

Readers might expect, then, that Vásquez has written a noir detective novel that investigates a crime that has gone unpunished for seventy years and restores some semblance of justice. Nothing, however, is that orderly in The Shape of the Ruins, which subverts the crime genre, presenting the hunt for culprits within the frame of what seems to be a Sebaldian memoir. His narrator, also called Juan Gabriel Vásquez, shares every last detail (birth, career, travels) of the author’s chronology. My research verified that author and narrator have the same friends, went to the same funerals, are influenced by the same literary sources, married the same woman, wrote the same acclaimed books, and won the same international awards. But above all, the narrator Vásquez is just as reluctant as his real-life counterpart to probe Colombia’s mangled history.

Advertisement

Throughout the novel we see the narrator (or is it the author?) trying to isolate himself and his family from the past that threatens to devour him and from the violence broodingly incarnated in Bogotá, described as a cemetery city, murderous, schizophrenic, poisoned, deceitful, furious, blood-stained. One of the reasons he abandoned Colombia for sixteen years of expatriation in Europe was the hope of leaving those specters behind. But they await him on a visit back home, and the author has, transgressively, chosen a major moment in his own life, just as his twin daughters face the danger of a premature birth, to overlap with the moment when his fictional alter ego will have to deal with the legacy of savagery, as if to signal that the curse of the country’s saga must be confronted if the girls are to have a future free of terror. He realizes this during a dinner at the house of Doctor Francisco Benavides in Bogotá on September 11, 2005.4

Vásquez has admitted in interviews that Benavides is based on a real person (Leonardo Garavito, to whom the book is dedicated), a friend who “put the ruins in my hands.” Those ruins, which actually exist (a photo is reproduced in the book), is a fragment of Gaitán’s spine preserved in a jar. Benavides inherited this relic from his deceased father, the country’s most accomplished forensic clinician, who collected vestiges of Colombia’s fractured past (including the skull of another major leader assassinated almost a century ago).

The narrator feels a strange energy pulsating from Gaitán’s remains, as if the nation that might have existed if bullets had not shattered those vertebrae is calling out to him to speak on behalf of the dead. Vásquez calls those bones “the ruins of a noble man,” the epigraph to the novel, a phrase lifted from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. It is a play that appears in other Vásquez novels as well as in “The Dogs of War,” a short story written about the time he was laboring on The Shape of the Ruins.5 That story laments how “the death of a great man can drag everyone else over the precipice,” in this case, Lara Bonilla, Colombia’s minister of justice, murdered by two of Pablo Escobar’s hit men in 1984. Osorio, the story’s narrator, notes that this terrorist act “produces domestic fury and fierce civil strife, produces blood and destruction and havoc.” Osorio adds, pessimistically, having lost his wife in a different bombing at a shopping center, “And there’s nothing we can do to avoid it.”

And yet, in The Shape of the Ruins, there is someone who believes that if the truth about the past were to be expressed publicly, the country might avoid future cataclysms. Carlos Carballo, a creature of the author’s imagination and one of the most intriguing characters in recent Latin American fiction, aggressively approaches the narrator at that Benavides dinner and will, from that moment on, hound him relentlessly.

Carballo has made it his mission to force the world to recognize that Gaitán’s assassination was planned by dark forces, though he is hard put to go beyond vague and wild conjectures about them. We will discover, at the forlorn end of the novel, the heartbreaking reasons behind his mania, why he turned into a fanatic who, in Benavides’s depiction, is

only good for one thing in this life, who discovers what that thing is and devotes all his time to it, down to the last second…. He eliminates from his life all that does not serve the cause. If it’s useful, he does it or gets it. No matter what it takes.

Carballo will ignore the facts and brazenly lie, commit forgery and fraud, and steal valuables from dear friends. Over the years he has become a consummate conspiracy theorist: every crime in history, every inexplicable twist and turn, is the result of a plot that has been covered up. That fixation is shared by others, among them the lonely listeners of Carballo’s Night Owls radio program, who gorge themselves on the hidden intrigues of yesteryear. We are regaled, therefore, throughout the book, with disquisitions on the Twin Towers, the sinking of the Lusitania, the death of Marilyn Monroe, the murder of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo, and, of course, the John F. Kennedy assassination (with stills from the Zapruder film reproduced and analyzed exhaustively). All of these, in Carballo’s mind, are somehow systemically connected, part of a monstrous pattern.

The narrator is wary of such speculations, which he finds intellectually lazy and ethically suspect, as they can be enlisted in any number of dubious political causes. Rather than that conspiratorial vision, “a scenario of shadows and invisible hands and eyes that spy and voices that whisper in corners, a theater in which everything happens for a reason…and where the causes of events are silenced for reasons nobody knows,” the postmodern narrator prefers to view history as “the fateful product of an infinite chain of irrational acts, unpredictable contingencies, and random events.”

Advertisement

Despite these objections and a strained, belligerent relationship between the two men, the narrator is unable to shake his fascination with Carballo, the sort of “tormented soul” for whom he has always felt an inveterate curiosity. Vásquez has written, in his collection of essays Viajes con un mapa en blanco (Traveling with a blank map) (2018), that the novel is a way of accessing the lives of others, a way “to penetrate, study, understand them in all their dimensions,” a means, according to Ford Madox Ford, whom he quotes, “of profoundly serious and many-sided discussion…[of] the human case.” Carballo’s very existence, then, challenges Vásquez’s own certainties, incites that many-sided discussion, precisely because he is so radically different.

Still, the deeper the narrator penetrates into Carballo’s furtive life, the more it becomes apparent that these two antagonists are closer to each other than either of them would care to admit. The narrator will show himself to be a conniving impostor, betraying those dear to him, cruel to grieving strangers, and thus no better than the man he is mocking. And is not the author himself a fanatic, as ruthless and deliberate in pursuit of his literary objectives as Carballo is in furthering his own projects, someone who does not mind exploiting the funeral of a friend or even the birth of his own daughters? This exposure of the failings and vulnerabilities of the author (or is it of the narrator?) was so pitiless that it often made me feel uneasy, even while I understood how essential such revelations were to the plot. If Vásquez, in whatever guise, were not ready to lay bare his own imperfections, how could he demand that Colombians venture into their dangerous past?

This is a demand that seems to go nowhere. Halfway through the book, the investigation into Gaitán’s murder comes to a standstill. It is now that the novel swerves in a startling direction. Gaitán is not the only martyred liberal who could have saved Colombia. In October 1914, the legendary General Uribe Uribe (so legendary that he became the model for Colonel Aureliano Buendía in One Hundred Years of Solitude) was killed in Bogotá by two hatchet-wielding carpenters, a murder that was covered up by those who were supposed to investigate it. The Shape of the Ruins plunges us headlong into the efforts of Marco Tulio Anzola, a young lawyer working as an inspector of public works and a real historical figure, to denounce the conspirators. That pursuit ends in failure, as he is censored, jailed, driven into exile, effaced from official annals.

By bringing this new investigator into the book and devoting over two hundred pages to his quest, Vásquez executes a risky literary maneuver that pays off brilliantly. For one, it shows that Gaitán’s murder (and those of other rebellious leaders) is part of a recurring design. And Anzola’s ruined life—the shape of his ruins—serves as a warning to anyone who dares to dispute the myths upon which the powerful have built their rule. But Anzola is also a mirror for both Carballo and Vásquez, someone these two rivals can bond over, almost a shared doppelganger. Besides showing them the courage required to bear the burden of stalking the truth, he holds, along with author and character, a fervent belief that the way to make sure that truth is not buried is to write a book. And so, Carballo will put Anzola’s self-published 1917 book, Quiénes Son? (Who are they?), in Vásquez’s hands.

Like the real Vásquez and the fictitious Carballo, I have read that book published a century ago. And like Vásquez, I have experienced a tremor at being in touch with the dead, grateful that a story like Anzola’s was able to stubbornly survive the attempts to suppress it, inspiring an extraordinary novel composed by a compatriot born fifty-six years after its publication. It is that novel, the one I am reviewing, that Carballo—animated by Anzola’s example—wants Vásquez to write. Cervantes would have been delighted: The Shape of the Ruins exists only because one of its main characters has demanded it. As Carballo says, “There are weak truths, Vásquez, truths as fragile as a premature baby, truths that can’t be defended in the world of proven facts, newspapers, and history books.” How, then, to “give them the space to exist”? The only way to make them survive, to do them justice, is to tell the tale.

In one of the most moving episodes in The Shape of the Ruins, the narrator meets another invented character, an admirable young woman in a hospital. Suffering from terminal cancer, she has decided to let herself die. Her real tragedy and regret, she says, is not the death that awaits her, but having left no stories behind. Many pages later, when Carballo tells his personal tragedy to the narrator and begs him not to let it be crushed by neglect, Vásquez cannot refuse. He continues to believe that the enigmas of the past can never be entirely resolved, but he can, at least, through the compassionate imagination, malentenderlo mejor—misunderstand that past in a better way, do his best to clear away the overgrowth of deceptions that hide the precarious truth.6 Carballo may be wrong about this or that crime, but he is right that people are fooled by the official versions of history (“What you call history is no more than the winning story, Vásquez,” he insists) and that it is indispensable to contest those institutionalized false certitudes. And he is right about Colombia’s perilous amnesia and right about Vásquez’s own complicity in that ceaseless process of forgetting. He says to the author, “You lack commitment, brother, commitment to this country’s difficult issues,” accusing Vásquez of sidestepping, in his earlier work, the most troublesome questions plaguing his land.

It is one of many allusions to Vásquez’s own evolution as an author scattered throughout the text, which illuminate the arduous road that led to The Shape of the Ruins. In his first two published novels, Persona (1997) and Alina suplicante (1999), which he disavows, Vásquez turns his back on Colombian history. In Persona, two couples play games of love and identity in Venice, without us knowing where they are from. Alina suplicante hovers between Paris and Bogotá, but its characters, beset by incest, infidelity, and solitude, do not register any interest in the internecine wars that were at that very moment ravaging Colombia. Their escape from each other seems, in retrospect, a metaphor for Vásquez’s own attempt to flee the ordeal of his native land. These apprentice works were followed by Los amantes de Todos los Santos (2001), a collection of sensitive and well-crafted short stories that were situated primarily in the Ardennes, again far from the love-hatred of his country that is so vital to Vásquez’s vision.7

There was, nevertheless, an earlier piece of writing that indicated where the author’s true obsessions lay. In the thesis he presented in 1996 for his law degree, “La Venganza como prototipo legal en la Ilíada” (Vengeance as a legal prototype in the Iliad), Vásquez, then twenty-three, uses Homer’s epic to question justice and the demand for reparations for those who have been slain, wondering how to prevent the ethical disintegration generated by the savagery of war—subjects that his major novels, all of them set in Colombia, will return to. Los Informantes (2004) delves into the fate of German immigrants persecuted in Colombia during World War II; Historia secreta de Costaguana (2007) focuses on the harrowing moment when the Colombian province of Panamá declared itself independent; El ruido de las cosas al caer (2011) masterfully portrays the devastation wrought by the narco wars of the 1980s; and Las Reputaciones (2013) skewers an eminent cartoonist, the “country’s conscience,” who may be guilty of a terrible crime, emphasizing that no Colombian, no matter how ostensibly pure, should presume he is not as soiled as the rest of the country.

The Shape of the Ruins would have been impossible had Vásquez not already explored in his previous works the complicated relationship between fathers and children; the flawed humanity of possessed, self-defeating characters who struggle with memory and betrayal; the role of chance and destiny in those lives governed by sensuality; and, over and over again, the difficulty of disentangling fiction from reality (just as we have trouble distinguishing the narrator from the author in The Shape of the Ruins).

One more thread joining all these books is an enthrallment with Western literature from Plutarch to Joseph Conrad and Philip Roth, a vast legacy that Vásquez has examined in his engaging collection of essays, El arte de la distorsión (2009).8 Rather than obsessing about pop culture, as is the wont of the McOndo generation of writers to which he purportedly belongs, Vásquez proudly and creatively appropriates the canon, including the authors of the Latin American Boom, the very idols repudiated by the McOndos, in what they understood as a form of parricide.9 Vásquez, for his part, has no problem embracing the titanic intellectual ambition of the great Latin American novels of the past, exploring, as these works did, the ways in which the grand events of history intersect with individual lives in all their intimacy and lay waste to them.

Perhaps the urgency that underlies the hunt for the truth in this new novel derives from its having been composed during the prolonged negotiations with the FARC guerrillas to end the longest insurrection in the Americas—that is, at the precise moment when the country was on the verge of a unique reckoning with its ferocious heritage.10 The Shape of the Ruins is suffused with the hope that there is a way to escape the traumas of the past as well as the fear, as Vásquez has said in interviews and Op-Eds, that his fellow citizens will miss the opportunity to look at themselves in the mirror, however painful that may be, and stop killing each other.

Colombia is about to find out if it will achieve a lasting peace or if it will, as the novel warns, once again fuck itself up.

-

1

See my essay on Vargas Llosa and José María Arguedas in Imaginación y violencia en América (Santiago: Editorial Universitaria, 1970). ↩

-

2

The definitive history of those events is Arturo Alape’s El bogotazo: Memorias del olvido (Bogotá: Editorial Pluma, 1984). Also see Herbert Braun, The Assassination of Gaitán: Public Life and Urban Violence in Colombia (Wisconsin University Press, 1985). ↩

-

3

McLean’s previous translations of Vásquez’s novels, all published by Riverhead, include The Informers (2009), The Secret History of Costaguana (2010), The Sound of Things Falling (2013), The Lovers on All Saints’ Day (2015), and Reputations (2016). ↩

-

4

The choice of the anniversary of the terrorist attacks in the United States is also quite purposeful, as the author wants readers to be aware of how the Colombian misfortunes are echoed elsewhere. ↩

-

5

It appears in the anthology Lunatics, Lovers and Poets: Twelve Stories after Cervantes and Shakespeare, introduced by Salman Rushdie (Sheffield, England: And Other Stories, 2016.) ↩

-

6

The term malentenderlo mejor comes from “‘Hay que mojarse, ganarse enemigos y molestar,’” an interview Vásquez gave to the Spanish newspaper El País, January 15, 2016. ↩

-

7

See David Gallagher’s review of this collection, as well as of the later novel Reputations, in these pages, October 27, 2016. ↩

-

8

He has even written a short biography of Conrad, Joseph Conrad: El hombre de ninguna parte (Bogotá: Panamerica Editorial, 2004), and incorporated the Polish writer into one of his novels as a protagonist. ↩

-

9

The Boom is represented by García Márquez, Cortázar, Vargas Llosa, Fuentes, and Donoso, but Vásquez would add Guimarães Rosa, Onetti, and Julio Ramón Ribeyro to the mix. For the McOndo generation (the word plays in part on “Macondo,” the name of the fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude), see Rory O’Bryen, “McOndo, Magical Neoliberalism and Latin American Identity,” Bulletin of Latin American Research, Vol. 30, No. 1 (March 2011). ↩

-

10

For insights into the FARC’s history, see Alma Guillermoprieto’s three reports in these pages, April 13, April 27, and May 11, 2000. For the problems the peace process is encountering, see the report by Human Rights Watch at hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/colombia. ↩