In 1962, two months after the Algerian War ended, Chris Marker went around Paris with the cinematographer Pierre Lhomme asking people what made them happy. The two of them were shooting a film, Le Joli Mai, about what had happened to the city during the twenty-three years since France had last been at peace. In the answers they got, happiness was rarely the dominant note. A sidewalk suit salesman griped about his wife. Two rich boys lurked around the stock exchange. A student from what was then the Republic of Dahomey remembered coming to Paris; he “tore the book apart,” he said, when his church-affiliated teachers told a self-serving story about the conquest of his home country.

The interviews were shadowed by dread. Even the cheerful respondents seemed insecure about the happiness they’d found. Marker enlisted his close friends Yves Montand and Simone Signoret to read the voice-over narration that runs through the film, he in the French version and she in the English. In the movie’s last moments they tell us that what they’ve been channeling is “a secret voice” reminding us “that as long as poverty exists you cannot be rich,” that “as long as people are in distress you cannot be happy,” and that “as long as there are prisons you cannot be free.”

Marker kept returning, across the vast body of films, writings, photographs, and multimedia projects he produced between the 1940s and his death in 2012, to the matter of what it meant to live a happy life. In an early essay about the novelist and playwright Jean Giraudoux, he quoted Sartre’s insistence that at certain moments the streets of Paris turn “fixed and clear” and offer up “an instant of happiness, an eternity of happiness.” The challenge, Marker thought, was to put such instants in a pattern, “to make the feeling of those privileged moments into a permanent conviction.” Sans Soleil (1983)—the dense, majestic essay film in which he overlaid footage from his many travels with the voice of an unseen woman reading letters from an unknown man—begins with a shot of three serene-looking young girls walking up a road in Iceland. “He said that for him it was the image of happiness,” the narrator tells us, “and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked.”

Isolated pictures of happiness “never worked” together. They had to be wrapped in other images—usually grimmer and more abrasive ones—for their significance to come across, because happiness itself, for Marker, was a fickle, unstable arrangement. Wars, coups, and imperial conquests were always quick to interrupt it. Near the end of Sans Soleil, the narrator reads a fragment adapted from the last letter the twenty-two-year-old Japanese kamikaze pilot Ryōji Uehara wrote his parents before he died at Okinawa:

In the plane I am a machine, a bit of magnetized metal that will plaster itself against an aircraft carrier. But once on the ground I am a human being with feelings and passions. Please excuse these disorganized thoughts. I’m leaving you a rather melancholy picture, but in the depths of my heart I am happy.

Threading together “disorganized thoughts” became Marker’s way of examining how people adapted to the conflicts, revolutions, and regimes that shaped their lives. “A literature that tried to disclose the essences of things,” he wrote, might have a “technique that seemed anarchic, open at first glance to charges of monotony and incoherence.” The same could be said of the essay films that defined Marker’s style: darting ruminations stitched together from original, found, and in some cases manipulated footage that only slowly divulge the full structure of their arguments and intentions.

He stocked these movies with references to his favorite film, Vertigo; allusions to Giraudoux, Proust, and Alice in Wonderland; graffiti; owls; elephants; and, most often, cats, which he loved because “a cat is never on the side of power.” To stay on the cat’s side, Marker had to distill his “permanent convictions” from his observations of how people accommodated themselves to power, or refused to.

His films dwell on figures who strain to expand their rations of freedom and happiness—like the revolutionaries whose disappointments course through the found footage in A Grin Without a Cat (1977)—or buckle under the pressures of their circumstances, like the Soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin, whose attachment to the ideals of the Russian Revolution Marker put under ambivalent scrutiny in The Last Bolshevik (1992). As a kind of ballast, he interspersed his movies with lone images of concentrated energy. Often these were of animals, or of beautiful women who broke the fourth wall: the bystander in Guinea-Bissau who locks eyes with Marker’s camera in Sans Soleil, for instance, or the young woman who blinks at the viewer in La Jetée (1962), a science-fiction story otherwise told entirely in still images.

Advertisement

Marker’s own attachments were subject to revision and shaded by skepticism and doubt. “Politics, the art of compromise,” he told two interviewers in 2003, “bores me deeply. What interests me is history, and politics only interests me to the degree that it is the mark history makes on the present.” That was not quite true—he followed the trajectory of the French labor movement closely, for example—but it drew a distinction that was crucial to him. The political questions that interested Marker had to do less often with strategy or policy than with the incompatible attitudes that he and his subjects often felt caught between: hope and pessimism, happiness and melancholy. “How,” he said he kept asking, “do people manage to live in such a world?”

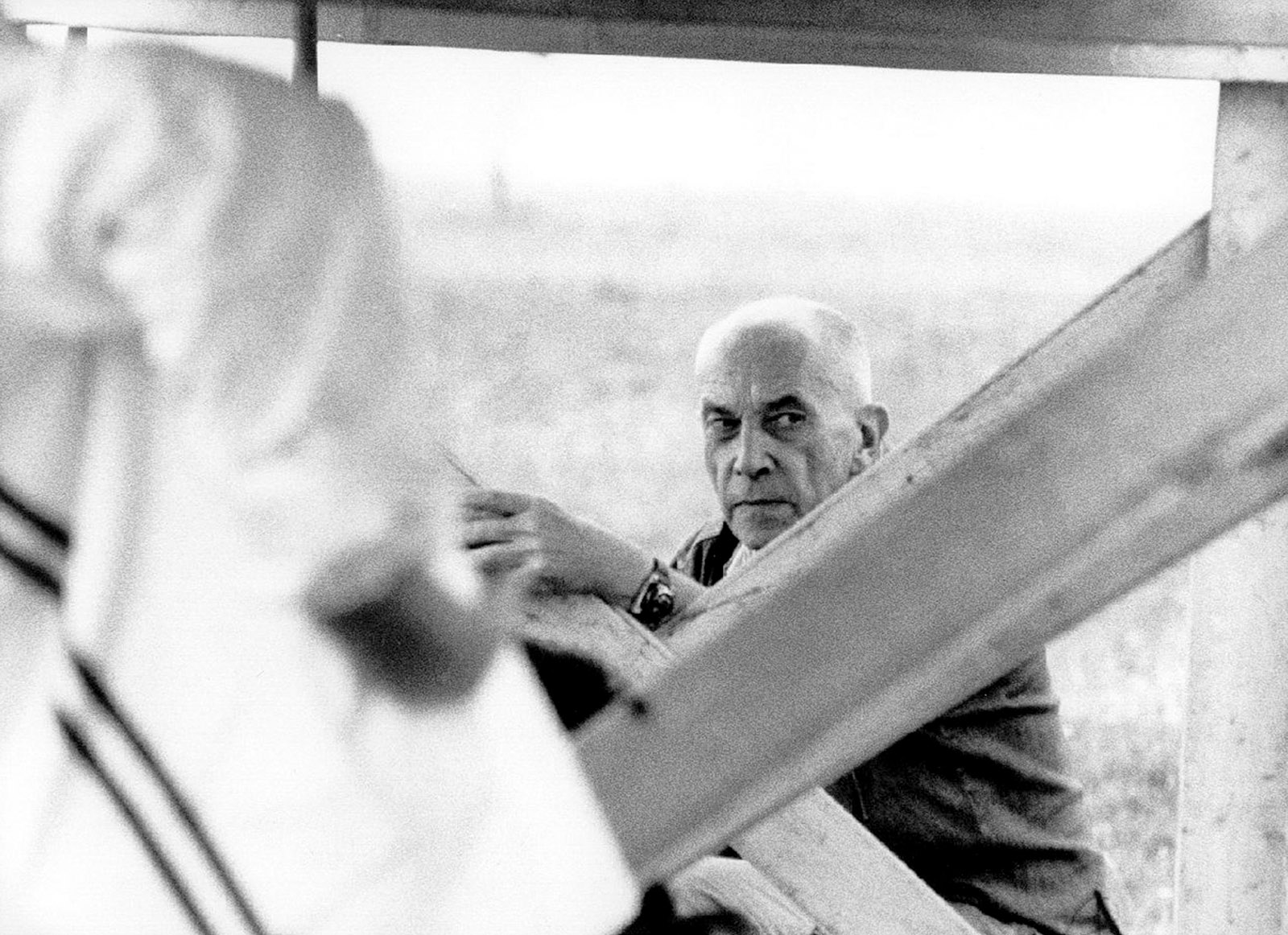

Marker was born in 1921, in the Paris suburb Neuilly-sur-Seine, with the burdensome name Christian Hippolyte François Georges Bouche-Villeneuve. His father worked for Crédit Lyonnais and during the Occupation—according to Jean-Michel Frodon’s essay in the lavish, authoritative volume that accompanied “Chris Marker, les 7 vies d’un cinéaste,” the Cinémathèque française’s Marker exhibition last year*—moved the family to Vichy, where he “worked for financial institutions with ties” to the Pétain government. Around the start of 1942, after putting out two issues he surely soon regretted of a Vichyite journal and briefly joining the “Veteran’s Legion” (Légion française des combattants), Marker fled to Paris, both because he was “disgusted” and for, as he put it much later, “the adventure.”

The following spring he slipped across the border into Switzerland, where he met up with members of the Resistance and did more than one stint in Swiss detention before returning to France and joining the Forces of the Interior. Some of the images that seem to have impressed themselves most deeply on Marker—the ruined, bombed-out cities in La Jetée, the fighter planes that fly through his work—emerged from these years. “People don’t see it,” he told his daughter, “but I always make the same film; I always tell the same story, in one sense or another…it’s the same shock that’s haunted me and followed me everywhere since I was twenty years old.” What struck the Swiss police about him were his “nervousness and his communist ideas.”

It was the first of many adventures in Marker’s long life. He traveled the world in the 1950s and later made numerous pilgrimages to Moscow and Japan; he cofounded, in 1967–1968, a radical filmmaking collective called SLON, which issued dozens of incendiary works of “counter-information”; edited, over long-distance phone calls with Eldridge Cleaver, a video called Congo Oyé about a delegation of Black Panthers who visit the People’s Republic of the Congo; oversaw the creation of a film school in Guinea-Bissau; and in the 1990s traveled to the former Yugoslavia to collaborate with Bosnian refugees. The year before he died, he made a logo for Occupy Wall Street.

At the same time he was private, migratory, and hard to pin down. When photos of him were requested he instead sent cartoons of Guillaume-en-Égypte, the beloved neighborhood cat who in the 1980s became a fixture of his studio and—as Judith Revault d’Allonnes and Étienne Sandrin write in their essay for the Cinémathèque catalog—his “persona, narrator, commentator, assistant, signature, alter ego, and spokesperson.” When a friend of his found herself pregnant and on her own in 1955, he offered to adopt and help raise her daughter, Maroussia Vossen, now a dancer and choreographer. In her tender memoir Chris Marker (Le livre impossible), Vossen remembers that he slept little and kept himself on a plain diet. He always seemed, she felt, to be “between two voyages, between two women, between two identities, between sky and earth.”

One of the revelations of the Cinémathèque’s show of selections from Marker’s vast archive was what a long paper trail this self-protective figure left behind: collages, scrapbooks, a collection of postcards, a short-lived comic strip, countless designs and works of graphic art, an extensive stock of letters. In some cases he took exotic names like “Fritz Markassin” and “T.T. Toukanov,” but most of the time, he said in a 2008 interview, “I chose a pseudonym, Chris Marker, that is easy to pronounce in most languages because I intended to travel.”

After the war Marker’s star rose quickly. In 1946 he started contributing to the left-wing Catholic journal Esprit, where he soon became an editor. He signed up for a theater workshop sponsored by Travail et Culture, an organization with close ties to the French Communist Party that promoted cultural exchanges among workers. Before long, he was editing its magazine, DOC, too. He was, very briefly, Antonin Artaud’s secretary. In his essays for Esprit, movies eventually emerged as a central subject. By 1952 he had a commission to make a documentary of his own, about the Helsinki Olympics.

Advertisement

Stalinism was the eruptive question of the day. For Marker, it became an early object for the mischief and irreverence that went on to fill his work. In his burlesque for Esprit about the expulsion of Tito’s Yugoslavia from the Comintern, Harry Truman and his “first chamberlain,” Humphrey Bogart, haggle over the phone with a general over “which Slavia” they need to worry about. Decades later, Marker wrote that the war had left him with “an absolute historical pessimism.” He admired some members of the French Communist Party and later collaborated with one of its staunch loyalists, the filmmaker Mario Marret. But he resented its “binary thinking” and resigned from DOC in short order when the Party tried to block him from publishing one of his heroes, André Malraux. “I do not belong to the generation that rose with the great wave of 1917,” he wrote in the 1990s. “It was a tragic generation, buoyed by a disproportionate hope, only to become the accomplice of disproportionate crimes.”

In the early 1950s, with Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet, he codirected an essay-film called Statues Also Die. Narrated by the actor Jean Négroni, it was Marker’s first major work, a scalding indictment that European museums and collectors had exploited African artists for their own profit. (“We buy their art and we degrade it.”) In its last minutes, the movie swelled to encompass the country’s racist suppression not only of artists but also of, among others, black labor activists. It was banned in France for more than a decade.

Marker made a name for himself during these years at the publishing house Éditions du Seuil, which issued his polyphonic novel Le Coeur Net in 1949 and five years later hired him to edit and design a series of travel books called “Petite Planète.” It gave him a perch from which to go abroad. His next four films—Sunday in Peking (1956), Letter from Siberia (1958), Description of a Struggle (1960), and Cuba Sí! (1961)—and his photo-book Coréennes (1959) show him looking for what, in his labyrinthine 1997 CD–ROM Immemory, he called “a rupture from the Soviet model” of communism. He went to Mao’s China, North Korea, Israel, Castro’s Cuba, and, to see the Soviet model, Siberia. At each stop his eye was drawn to street fairs, markets, parades: sites where bodies milled densely and people were at their most exuberant. He paired these images with narrations that occasionally celebrated the “models” he found (in the cases of Israel and Cuba) but more often swam from one sly observation to the next.

In later years, Marker refused to screen these early travelogues; he found them “rudimentary.” Many disagreed. In an influential essay, André Bazin celebrated the scene from Letter from Siberia in which Marker played the same footage of Yakutsk three times with three different commentaries: a parody of Stalinist propaganda, an anti-Soviet screed, and a tempered appraisal. A man the first narration calls a “picturesque denizen of the Arctic reaches” becomes a “sinister-looking Asiatic” in the second, and then a “Yakut afflicted with an eye disorder” in the third. The rhetorics of Stalinism and of anticommunism were both bankrupt, and that of the “objective” narration, Bazin thought, was “even more false than the two opposed partisan points of view.” By throwing out these options one by one, Marker left the images themselves, baffling and mute, for the viewer to puzzle over. What came next was the job of wrapping them in a new language, with a new tone, wry where its predecessors had been humorless, sensual where they had been stiff, perceptive where they had been myopic. That would be the tone of Sans Soleil.

Back in Paris, Marker worked to develop that tone. It glimmers through the rueful narration of Le Joli Mai and through the scenes of stolen time in La Jetée between a time-traveling prisoner from a dystopian future and the young woman who loves him and eventually sees him killed. What let it emerge fully were the political convulsions of the late 1960s, which both revitalized Marker and widened his capacity for grief. In 1967 he got an invitation to film workers at the Rhodiaceta textile factory as they went on strike demanding time and energy to spend “on the cultural level.” When they bristled at points of tone and emphasis in À bientôt, j’espère (1968), the admiring film he and Mario Marret shot about them, he encouraged them to form a collective called the Medvedkin Group, which in the following years made about a dozen vigorous, formally adventurous movies.

Alexander Medvedkin himself became, for Marker, a symbol of a kind of faith he was rarely able to share. He had marveled at the ingenuity of Medvedkin’s films from the 1930s; later he learned that Medvedkin, in his desperation to keep working, had made a tribute to Stalin less than four years after the regime banned his greatest film. For Marker, the director’s life came to seem like a rebuke to “the present manicheism about Soviet history—as if between the Nomenklatura and the Dissidents, there were nothing but a shapeless crowd.” After Medvedkin died, Marker marveled, in The Last Bolshevik, that his old friend had maintained a communism purer and more devout than that of the regime that extracted so many compromises from him. Medvedkin’s faith, Marker suggested, was also a kind of trust in the power of montage to put the world in order. The Soviet director wept the first time he realized that two of his disparate images made sense together.

By the mid-1970s Marker seemed to doubt that his own images could bring such coherence to the splintered lives they showed. During this period, one of his important collaborators, the editor Valérie Mayoux, ventured into the back of the office of SLON (then renamed ISKRA) and came across boxes of unused footage shot by the group’s members. “There’s a film to be made here,” she told Marker. The film he made, A Grin Without a Cat, was his most tortured account of the defeats of the New Left. In Vietnam, an American GI gives enthusiastic live commentary of the carnage unfolding under his plane; in France, police beat student demonstrators; in Chile, a US-sponsored coup destroys Salvador Allende’s experiment in democratic socialism.

The resulting movie was a catalog of details—like Castro’s useless efforts to fiddle with a fixed microphone during a speech in Moscow—observed with spritely pessimism by a rotating set of narrators. It flirted with despair but kept it at bay, as if by the sheer intensity of Marker’s melancholy investment in the struggles he followed, the extent of his interest in the individual lives they absorbed, and the depth of his gratitude to the camerapeople who risked their lives to get the footage he used. In the film’s written preface he stressed the need to reunite “all those voices that only the lyrical illusion of 1968 had allowed, for a short moment, to meet”—before “the backlash came” and “everyone fell back into their self-congratulatory or furious monophonies.”

Not everyone approved. In a roundtable for Cahiers du Cinéma, younger critics delivered stern verdicts on the film’s hang-ups and omissions. For Serge Le Péron and Jean Narboni it was a relic of the thinking of an older generation, one still stung by the legacy of Stalinism. What bothered Le Péron was “the idea of attributing a kind of paternity to the children of May 68.”

Marker responded with tolerant affection to this younger wave of activists who rejected his parentage. “It was a generation that often exasperated me,” the narrator’s correspondent says in Sans Soleil:

But it screamed out that gut reaction that better adjusted voices no longer knew how, or no longer dared to utter…. They wanted to give a political meaning to their generosity, and their generosity has outlasted their politics. That’s why I will never allow it to be said that youth is wasted on the young.

Young people bustle through Sans Soleil: the gamers who spend their days in the computer section of a Tokyo department store, “exercising their brain muscles like the young Athenians at the Palaistra”; the girls in the Bijagós Islands who “choose their fiancés”; those children on the road in Iceland. But it is the work of an older man. What had come to interest Marker were, he admitted, “rather unexciting problems for revolutionary romanticism: to work, to produce, to distribute, to overcome postwar exhaustion, temptations of power and privilege.” He wanted to know how people coped with the disenchantments that the heroes of A Grin Without a Cat had tried to move beyond.

Marker, for his part, was looking for new sorts of utopias. He was drawn to early computer technologies, he proposed at the end of Sans Soleil, because they made it seem possible that one day “poetry will be made by everyone.” It excited Marker that they let their users build and populate new worlds, like the “zone” a fictional video artist creates in Sans Soleil by passing footage through an image synthesizer, or the “hypotheses” about the future of trade unionism—hopeful, dire, and “gray”—a computer generates in the short film 2084 (1984). When the first personal computer came on the market, he said it was “THE language I’ve been waiting for since I was born.”

He shot his late feature The Case of the Grinning Cat (2004) on a cheap digital camera and filled it with footage of young Parisians at marches, flash-mobs, and die-ins. Digital video had given him the freedom to “make a whole film,” he said, “with my own ten fingers.” He burned the DVDs himself and sold them at a market near his studio. Four years later he joined the online virtual world Second Life, where with the computer artist Max Moswitzer he designed an archipelago called L’Ouvroir that lay under a network of floating platforms and orbs. An avatar of Guillaume the cat gives a tour that leads through a museum of photoshopped paintings. As the video passes from wall to wall, pictures that seem cute and whimsical give way to ones that show tanks, bombed-out cities, and TV sets perched on mounds of skulls.

Marker said he took inspiration for L’Ouvroir from The Invention of Morel, Adolfo Bioy Casares’s 1940 novella about a political exile who lands on an island populated, he finds, by a mysterious group of partygoers. They don’t acknowledge his presence, and only after he falls in love with one of them does he discover that they belong to a three-dimensional recording that plays across the island on a loop. Marker kept admitting to similar realizations. The great, terrible moment, for him, was when what seemed like a genuine chance at happiness, clarity, or revolution turned out to be a flicker of something that had already come and gone. In hindsight, he wrote in 2008, he felt that what A Grin Without a Cat really showed was “the unending rehearsal of a play which has never premiered.”

-

*

When the exhibition moved to Brussels it was called “Memories of the Future.” ↩