In 1978 the trumpeter Don Cherry was asked about his music in a documentary for Swedish television. “Well, for one thing,” he replied, “it’s actually not my music, because it’s a culmination of different experiences, different cultures, and different composers that involves the music that we play together.” This was far more radical than the declaration of self-determination that the alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman chose as the title of his 1961 album This Is Our Music, featuring Cherry on trumpet. Cherry, a follower of Tibetan Buddhism, saw himself as a “student of life” in the “university of life,” as he wrote in his endearingly humble CV. He was indifferent to earthly matters of credit and intellectual property: what mattered to him was the experience of what he called “complete communion” or “togetherness”; music belonged to everyone, and therefore to no one.

Cultural history is seldom kind to those who renounce ownership claims. Cherry has been largely taken at his word, as if he merely inserted himself, like Zelig with a trumpet, into some of postwar jazz’s most important groups. But he was an extraordinarily innovative figure, first as an apostle in Coleman’s free jazz movement, which liberated improvisation from the chord progressions of bebop; then as a leader of musical globalism—what later became known as world music. When he arrived on the scene, he didn’t sound like any other trumpeter, partly because he played the cornet or the “pocket trumpet,” a tiny horn made in Pakistan that he had picked up at a pawnshop, instead of the traditional B-flat trumpet. (He preferred smaller horns that allowed him to feel the vibration of his sound.) His playing sounded cracked, wobbly, sometimes outright splintered. Rather than clear, bell-like lines, he created radiant splatters, jubilant, often arpeggiated scribbles of sound.

Like other apostles, Cherry not only spread the gospel, he reinterpreted it, multiplying its potential applications. By the time Coleman won converts to free jazz, Cherry had already moved on to the next thing, creating extended suites teeming with improvisation but threaded together by sweet, hummable themes that seemed to pop up out of nowhere. When other jazz musicians began to copy him, he became a student again, traveling the world and performing with improvising artists from the global South, as well as avant-garde luminaries like Terry Riley, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Wilson, and Lou Reed. Out of these travels came a new language, multiethnic, pan-spiritual, and often trance-like. He called it “organic music,” since he felt music should be “a natural part of your day.”

“Don liked to drop in and do his thing,” Sonny Rollins told me. “He always wanted to travel light.” His music was buoyed by what Italo Calvino called “the secret of lightness,” the gift of the artist “who raises himself above the weight of the world,” aware that “what many consider to be the vitality of the times—noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring—belongs to the realm of death.” Cherry’s lightness inspired the musicians he met, but it has obscured the depth of his achievement, as if he were too celestial to leave a footprint in musical memory. His nomadism has also bewildered jazz historians, because he was “never where you expected him to be,” as the French saxophonist Raphaël Imbert has written.

At once everywhere and nowhere, Cherry’s traces are scattered across hundreds of recordings, some available only on YouTube (where some of his live performances can also be seen, notably a stirring 1971 concert in Paris with the South African bassist Johnny Dyani and the Turkish drummer Okay Temiz). But in the last few years, small labels have been bringing a number of his albums back into circulation. The latest are two sessions recorded in Paris nearly twenty years apart: Studio 105, Paris 1967, a live trio concert for French radio released for the first time; and his 1985 foray into pop, Home Boy, Sister Out. To listen to his music today is to be struck not only by its inventiveness but by its sheer freshness, what Cherry called “now-ness.” Neither album is flawless—Cherry’s was an art of imperfection—but both contain flashes of spine-tingling beauty and fascinating echoes of his remarkable journey.

Cherry was born in 1936 in Oklahoma City to a black man and his Choctaw wife. When he was four, the family moved to Los Angeles and settled in Watts. Cherry’s father ran the bar at the Plantation Club on Central Avenue, where Billy Eckstine’s and Artie Shaw’s bands performed. He discouraged his son, who played piano and sang in a Baptist church choir, from getting mixed up in jazz. But the lure of the Central Avenue scene was irresistible, and in junior high Cherry took up the cornet. He cut classes at Fremont High School to study under the legendary jazz instructor Samuel Brown, who led a student swing orchestra at Jefferson High School. Truant officers threw him into the Jacob Riis reform school, where he met a young drummer named Billy Higgins. Before long they were touring with the tenor saxophonist James Clay.

Advertisement

In his late teens, Cherry was introduced to Coleman by the poet Jayne Cortez, Coleman’s first wife. Coleman, who’d just arrived from Texas, was the first man he’d ever seen wearing his hair long, and to the future apostle “he looked like the Black Jesus Christ.” A circle soon formed around Coleman, including Cherry; Higgins; Charlie Haden, a white bassist from the Ozarks; and a drummer from New Orleans, Ed Blackwell, who later replaced Higgins in the Coleman quartet. They had one of their first gigs at the Hilcrest Club in 1958, in a quintet led by the pianist Paul Bley, but soon decided to go piano-less, as a quartet. And in November 1959, they made history at New York’s Five Spot, where Coleman’s revolution was officially launched.

Cherry’s contribution was crucial. While Coleman spoke in riddles and cryptic aphorisms about his approach to improvisation, Cherry could explain (or translate) it with clarity, patience, and illustrations on his horn. In Los Angeles he was known as “Chord Man,” because of his fascination with chords, and he showed that Coleman’s revolution, which seemed to reject chords altogether, was not so much a rupture as a return to first principles: blues feeling, melodic invention, spontaneity of expression. Bebop’s rigidification into a style had undermined these principles; “style,” Cherry often said, is “the death of creativity.”

In their musical dialogues, Coleman and Cherry achieved a degree of complicity with few equals in the history of music, matched in jazz only by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. It was not always clear who was leading and who was following, since Cherry knew Coleman’s tunes better than Coleman himself. (Coleman revered his “elephant memory.”) Sometimes the rest of the band would sit out for a few minutes, leaving Cherry and Coleman to trade musical lines with such delight that you’d think their horns had been invented for the purpose.

Other saxophonists took notice. Rollins, who hired him in 1962, told me, “I wanted to get that new, free sound, and Don had a great musical mind.” Cherry spoke with great reverence of all his “teachers,” particularly Coleman, his “guru,” and the tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler, a “pure folk musician.” But the most important relationship he formed in those years was with Monika Marianne Karlsson, a Swedish textile artist known as Moki, whom he met in Stockholm in 1963, while on tour with Rollins. Moki was involved with a musician from Sierra Leone, with whom she had a daughter, Neneh, a year later, but she and Cherry became a couple shortly after the birth of Neneh, and Cherry raised her. Moki shared his openness, his love of travel, and indigenous roots: her parents were Laplanders who had raised her in a small town in northern Sweden.* Cherry loved living in Europe, where, Neneh told me, “he could walk the streets and be himself, and be free of the more complicated history of the United States, where at times he felt like he was back in shackles.” He was free, too, from the shackles of heroin, a habit he’d picked up in the late 1950s.

It was in Europe that Cherry began to develop his voice as a composer. His earliest inspirations came from Morocco, where, in the village of Jajouka, he had his first experience of “living in the mountains” and his first exposure to a more communal, ritualistic form of music-making. The musicians there were not simply playing but “living with” music. How, he wondered, could he move beyond short tunes and create a similar feeling of a music without limits, the experience of an infinite dance? The answer, he realized, was right under his nose. Cherry had memorized thousands of songs from throughout the world on his short-wave. (He never turned the radio off, even when he was sleeping.) Why couldn’t he make music from them? He began to dream of a “symphony for improvisers” that would skip from one tune to another, like flipping the dial on his radio.

One of his first European recruits was a German pianist, Karl Berger, whom he met in 1965 at a café in Paris. Berger, a protégé of Theodor Adorno who was in town to continue his studies in musicology, recognized Cherry and asked if they could play together. “Rehearsal is at 4:30,” Cherry replied, giving him an address. Berger arrived and immediately found himself playing vibraphone in a quintet with an Argentine tenor saxophonist, Gato Barbieri, an Italian drummer, Aldo Romano, and a French bassist, Jean-François Jenny-Clarke, none of whom spoke one another’s language. Cherry would lead them in a tune, only to suddenly signal for them to begin another. “Working with Don Cherry, you ended up every day in another country,” Berger told me. “We were new to this kind of thinking, but it made total sense to me. Why not use a melody that somebody played in Afghanistan and play it right after one that was done in South Africa? It was just like child’s play, beautiful, open child’s play.”

Advertisement

Cherry’s band performed these “cocktails”—twenty-minute suites of improvisation, channeling tunes of various origin—at Le Chat Qui Pêche in Paris, then in a month-long residency at the Café Montmartre in Copenhagen in March 1966. The quintet’s music provided the template for Complete Communion, Symphony for Improvisers, and Where is Brooklyn?, Cherry’s three great albums of 1966 released on the Blue Note label, in which he joined forces with leading members of the New York scene, including his former colleague in the Coleman band Ed Blackwell, who melded jazz swing and the dancing rhythms of New Orleans marching bands. The albums feature some of the most infectious free jazz of the era: taut yet supple; full of shrieks and hollers but also full of in-the-pocket grooves; and, above all, exuberant, bubbling with the joy of a man who has never forgotten what drew him to music in the first place.

It’s the sort of joy we hear in “Infant Happiness,” the twenty-four-minute track that opens the 1967 trio recording from Studio 105 in Paris, featuring Berger on vibraphone and piano and Jacques Thollot on drums. Most of the themes on the album are versions of tunes from Cherry’s Blue Note cocktails. But what a distance he had traveled musically since his return a few months earlier from New York, where he’d fallen back into his heroin habit and pawned his horn. His cornet playing is so bright it might as well be powered by solar energy. The components of his mature phrasing have fallen into place: cascades of syncopated, boppish notes, exquisite in their irregularity; annunciatory piping, as if proclaiming the arrival of a group of troubadours; sustained cries that seem to reach for the clouds. Even more striking is the embrace of sounds and tonalities foreign to jazz. Cherry plays bamboo flute and gong, as well as cornet and piano, while Berger and Thollot generate sounds from a battery of percussion instruments. One has the impression of being enveloped by a lush profusion of bells.

The use of non-Western instruments and timbres was hardly unusual in free jazz, but in Cherry’s work they were not merely decorative but structural, reflecting a passionate immersion in other traditions rather than a passing flirtation. He spent much of the late 1960s and 1970s seeking new sounds, traveling long distances to apprentice with musicians he admired or just to play in the fields with farmers and goat herders. He taught himself new instruments: the saron, a metallophone used in Javanese gamelan; the Malian doussn’gouni, a West African hunter’s harp that reminded him of the Delta blues; and the conch shell, which he claimed to prefer to the trumpet. He went to India to study dhrupad singing and tabla, and took lessons with the singer Pandit Pran Nath, the teacher of Terry Riley and La Monte Young.

He began to use his voice more often—singing, humming, sometimes just whispering, in an inimitable blend of gospel and blues, hymns he’d learned from the South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim and Eastern religious traditions. Fans of his earlier work complained that he wasn’t playing enough trumpet, but Cherry considered himself “essentially a singer”: trumpet was just “a voice for what I wanted to say in music.” On his best albums of the late 1960s and early 1970s—the live duets with Blackwell, Mu, Parts 1 and 2; the Eastern-tinged orchestral works Eternal Rhythm and Relativity Suite—the slightly frenetic free jazz of his short-wave period gave way to a folk style rooted in ostinatos and chant, open to nature, often devotional in feel.

A wiry, beautiful man with a beatific smile and angular, reddish-brown features that revealed his Native American ancestry, Cherry cut the profile of a countercultural gypsy. In 1969 he showed up at James Baldwin’s apartment in Istanbul in “a crazy-quilt costume as for some never-ended harlequinade,” as a journalist in Ebony described him. In town to give a concert, he ended up composing the score for a play that Baldwin was directing. Cherry was incapable of meeting a fellow artist without attempting a collaboration: he created music wherever he wandered, practicing what the Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant called the “thought of errantry.” One of the few places he stayed for any length of time was Dartmouth College, where he taught for a semester in 1970 and made the electro-acoustic duet Human Music with his colleague the composer Jon Appleton. One student compared Cherry’s class to “a religion course taught by someone present at the Last Supper.” The metaphor was apt in another sense, since Cherry’s travels had reinforced his belief that music could be a vehicle for communal storytelling and prayer.

Before leaving Dartmouth, Cherry “borrowed” from the university museum a rare flute from a Native American tribe in Taos, to whom he dedicated a short, haunting piece, “Blue Lake.” He promised to return it the following semester, but after the bombing of Cambodia, “I decided I was done with America.” He and Moki moved with Neneh and their two-year-old son, Eagle-Eye, to Tågarp, a town three hundred miles southwest of Stockholm, where they lived on a farm in a red schoolhouse. They cut their own wood and grew their own food. At one point Cherry ate only brown rice, “to remind myself there were starving people in the world.” He practiced outdoors because he liked to feel the wind on his face when he played. Moki designed tapestries and rugs with Buddha figures and naked bodies in Edenic pastoral scenes. They gave workshops in schools and in 1971 were invited to produce a live-in happening at the Geodesic Dome of Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art.

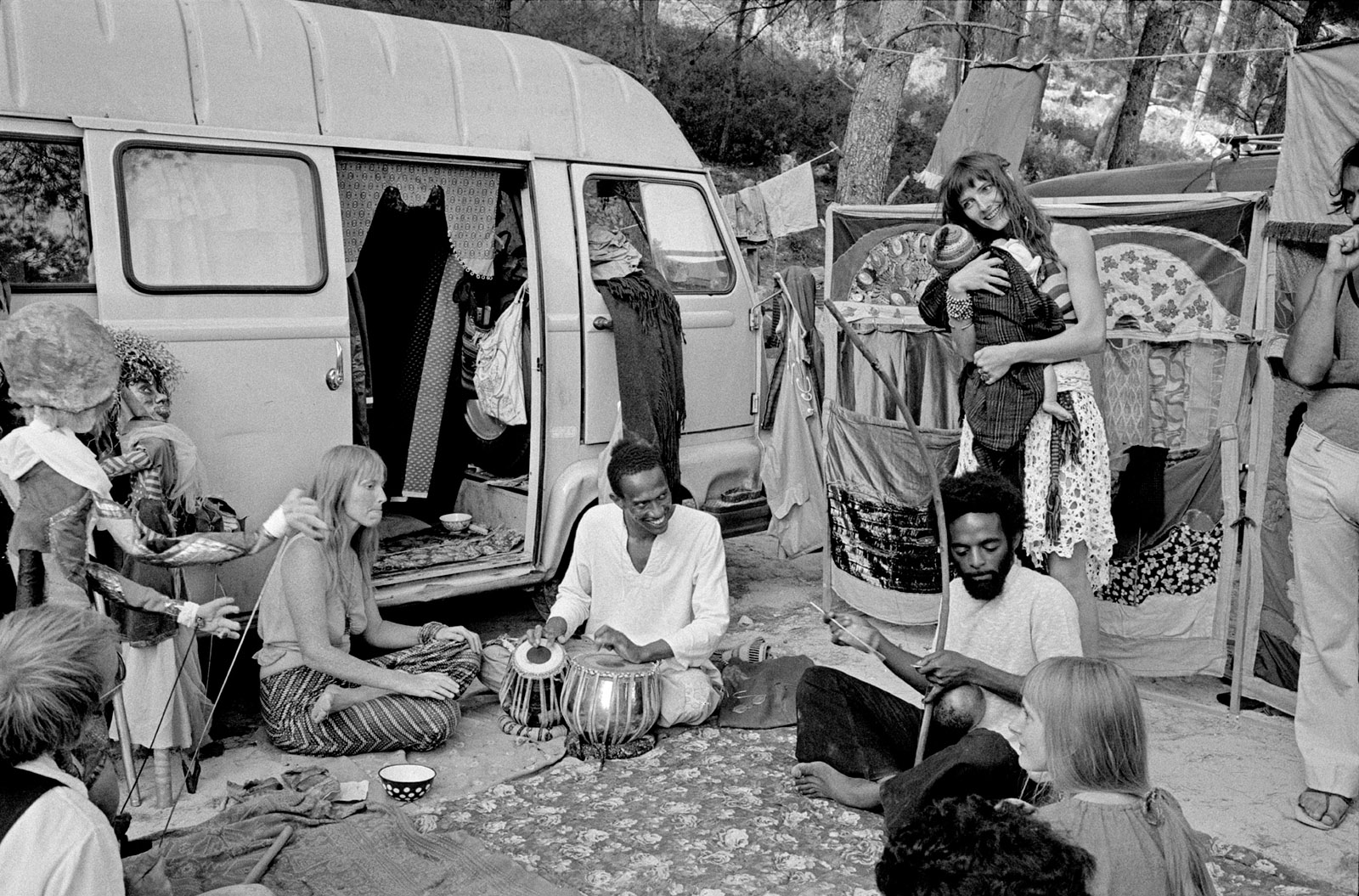

The Swedish jazz scene was transformed by Cherry’s presence: under his influence, horn players consumed by Coltrane began to explore their own folk traditions for the first time. Musicians from around the world came to visit the farm in Tågarp and often stayed for months, becoming part of Cherry and Moki’s “Organic Music Society.” When Cherry went on tour in Europe, the family traveled in a VW bus, which Moki painted and Cherry redesigned so that he could sit in the lotus position behind the wheel, using his hands to work the brakes and the accelerator. Moki’s psychedelic textiles hung from the stage at his concerts, and “we tried to reproduce in our music the expression and meaning of these colors.”

Cherry never stopped playing the kind of free jazz that had brought him renown in Coleman’s band. He periodically reunited with his “guru,” notably on Coleman’s 1972 Science Fiction sessions, and in the mid-1970s he formed the quartet Old and New Dreams with three other Coleman veterans, Blackwell, Haden, and the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman. But he directed most of his energy to combining what he called the “three ways of playing: a mystical fashion, a popular fashion, and a classical way” in a “synthesis…that would express, together, a real unity.” Cherry heard this unity in Coltrane’s late spiritual music and believed it “might give birth to harmony and not only musical harmony.”

This vision of transcultural harmony underpinned his most beautiful work of the second half of the 1970s: the electric jazz masterpiece Brown Rice (1975); Music/Sangam (recorded in 1978, but released five years later), a hypnotic duet with the tabla player Latif Khan; and the three albums he recorded with Codona, a trio with the Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos and the American sitar player Collin Walcott. It also won him the admiration of minimalist composers such as Meredith Monk and Philip Glass, both of whom shared his fascination with Buddhism and the music of the East. Three of the four tracks on Brown Rice, recently reissued on vinyl, were recorded by Kurt Munkacsi, Glass’s sound engineer and producer. “It absolutely influenced the work I did with Philip Glass,” Munkacsi told me, “and it led to Philip using some of those ethnic instruments.”

On paper, Brown Rice sounds like it should have been a disaster: a free jazz band improvising to Buddhist chants and ragas, amplified by wah-wah pedals and other electronics, and swirling with drones (produced by Moki on the tamboura), bells, and voices, including Cherry’s own. Yet for all its slick futurism, Brown Rice is a surprisingly organic work of art. This is partly because of the complete communion of Cherry and the nucleus of the ensemble: Haden, Higgins, and Frank Lowe, whose ecstatic screams on tenor saxophone detonate thrilling explosions of blues lyricism. But musicianship alone can’t explain the improbable magic of Brown Rice or of Cherry’s work in Codona. What made his musical globalism so persuasive is that his relationship to his “ethnic” sources was intuitive, not ethnographic—“the exoticism of dreams,” as the critic Alain Gerber put it.

With Codona, which performed together from 1978 until 1984, when Walcott died in a car accident, Cherry came closer than ever to achieving a geographically indeterminate music of land and sky steeped in collective memory, as if he had located that elusive point where all the world’s vernacular traditions meet. Its work was dreamy and poetic, full of silences and arresting, slightly asymmetrical patterns, like a Malian mud-cloth or one of Moki’s tapestries. To listen to Codona is to imagine you’ve stumbled upon field recordings from ceremonies performed by some transcultural tribe of the future.

On the group’s recordings—reissued as a boxed set in 2009, The Codona Trilogy, by ECM—Cherry delivered some of his most imaginative playing on trumpet: he could evoke a firefly at one moment, a whirling dervish at another. He also told stories, like “Clicky Clacky,” a blues tune, half sung, half spoken, about the railroad tracks near where Moki had grown up, punctuated with the sound of train whistles; he accompanied himself on the doussn’gouni, the ancestor of blues guitar, hinting at the blood on the tracks that metaphorically ran from his ancestral history to the childhood of the woman he loved.

Although quiet, serene, and nearly ambient, Codona’s music was also gently proselytizing; in the words of the critic Kodwo Eshun, it proposed a “reorientation point for a new planetary values.” Cherry was a musical disciple of Ornette Coleman, but he also carried on the legacy of Coltrane’s pan-spiritualism, and for the musicians who worked with him in those years, he was not just a seeker but a sage. “Don was the kind of teacher who gives you confidence by saying one sentence,” the singer Ingrid Sertso told me. Inspired by Cherry’s teachings, she and Karl Berger, her husband, established a school in the early 1970s, the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, which remains a center for improvised music.

The one person he couldn’t save was himself. In the late 1970s Cherry returned to New York and slid back into his heroin habit. He moved with Moki and their children into a loft in Long Island City, where their neighbors were Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth of Talking Heads. For all his love of nature, he was thrilled to be back on the streets of New York. He roller-skated around the East Village, wearing purple pants and a hat with a propeller, practiced his trumpet in abandoned lots, and played the doussn’gouni for children in Harlem. But his running buddies in New York were fellow addicts like Frank Lowe and the drummer Dennis Charles, whose apartment was a shooting gallery. By the early 1980s, Moki had left him.

Cherry took stock of his New York experiences in Home Boy, recorded in 1985 in Paris, where he was living near Montparnasse. He appeared on the cover in profile against a white stucco background: his looks are still striking, but his expression is worn, guarded. An album of urban pop, all but devoid of the blissed-out spiritualism of his 1970s work, Home Boy is something of an outlier in Cherry’s catalog. Produced by the guitarist Ramuntcho Matta (the artist Gordon Matta-Clark’s half-brother), it was conceived as a showcase for Cherry’s singing, since heroin had worn away at his embouchure. Cherry is a crooner of modest gifts, and the musical accompaniment—a collage of guitar, percussion, drum machines, and trumpet over-dubs—feels like a hipster soundtrack Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring might have danced to at the Mudd Club. But the album has a gritty honesty, a rueful sense of humor, and Cherry’s usual flair for storytelling. There’s even a song called “Rappin’ Recipe,” in which he explains how to make sweet potato salad, including measurements for each ingredient.

Jacques Denis, in his liner notes to the reissue, describes the album as “a perfect summary of everything Don Cherry’s records have always aimed at demonstrating: an openness to otherness.” This seems to me almost exactly wrong. There are some reggae beats, and on “Bamako Love” Cherry’s gorgeous trumpet solo is woven into a quilt of West African rhythms and wordless vocals. But for the most part, Home Boy finds Cherry drawing comfort from the great black music of his youth in Watts: gospel and soul, blues and doo-wop. In “Alphabet City,” he comes across as down on his luck but still resilient, having survived years of temptation and danger: “Home boy, home boy, where you been?/I been around the corner taking a sniff again.” Ignoring warnings that he’ll “end up in jail,” he’s running down “Avenue A, Avenue B, Avenue C, Avenue D, ain’t no E…down by the river!” The price he paid for this journey to the end of the night is suggested by the title of another song, “Treat Your Lady Right.”

Cherry had only ten years to live. He made a few good records, notably Multikulti, a musically omnivorous survey of his career, and the straight-ahead quartet album Art Deco, where he reunited with his old employer in Watts the tenor saxophonist James Clay. In 1993 he conducted a Mass for All Religions at the Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C. But he could sometimes barely get a sound out of his trumpet on stage, and in 1993, while he was living in San Francisco, his girlfriend died in his arms of an overdose. His old bandmate Gato Barbieri passed him on the street and pretended not to recognize him. The bassist William Parker saw him outside a Chinese restaurant on the Lower East Side and mistook him for an elderly Chinese man. He was broke and physically fragile, and in 1995 he developed liver cancer.

His family in Europe, always his sanctuary, took him in. Neneh—by then a pop star and pregnant with her second child—rented a casita for him in Málaga, next to her house in the mountains; a thicket of wisteria grew from the patio. Shortly before he moved in, Moki came to prepare the house for his arrival. She hung one of her tapestries depicting the Chenrezik, the most revered of the Bodhisattva, on the outside of the house, so that he would see it from the driveway. He spent his last few weeks there. Two days before he died at fifty-eight, he asked Neneh if he could touch her belly. “He wanted to feel the life force,” she told me. His last request was to be taken to the water a few miles from Neneh’s house. “He wanted to see the sea one last time.”

-

*

In 1967 Cherry and Moki appeared together in a short experimental film, Music, Wisdom, Love, shot in and around Paris and scored by Cherry, in which he does battle with gargoyles in Notre Dame and Moki kisses him from behind barbed wire. ↩