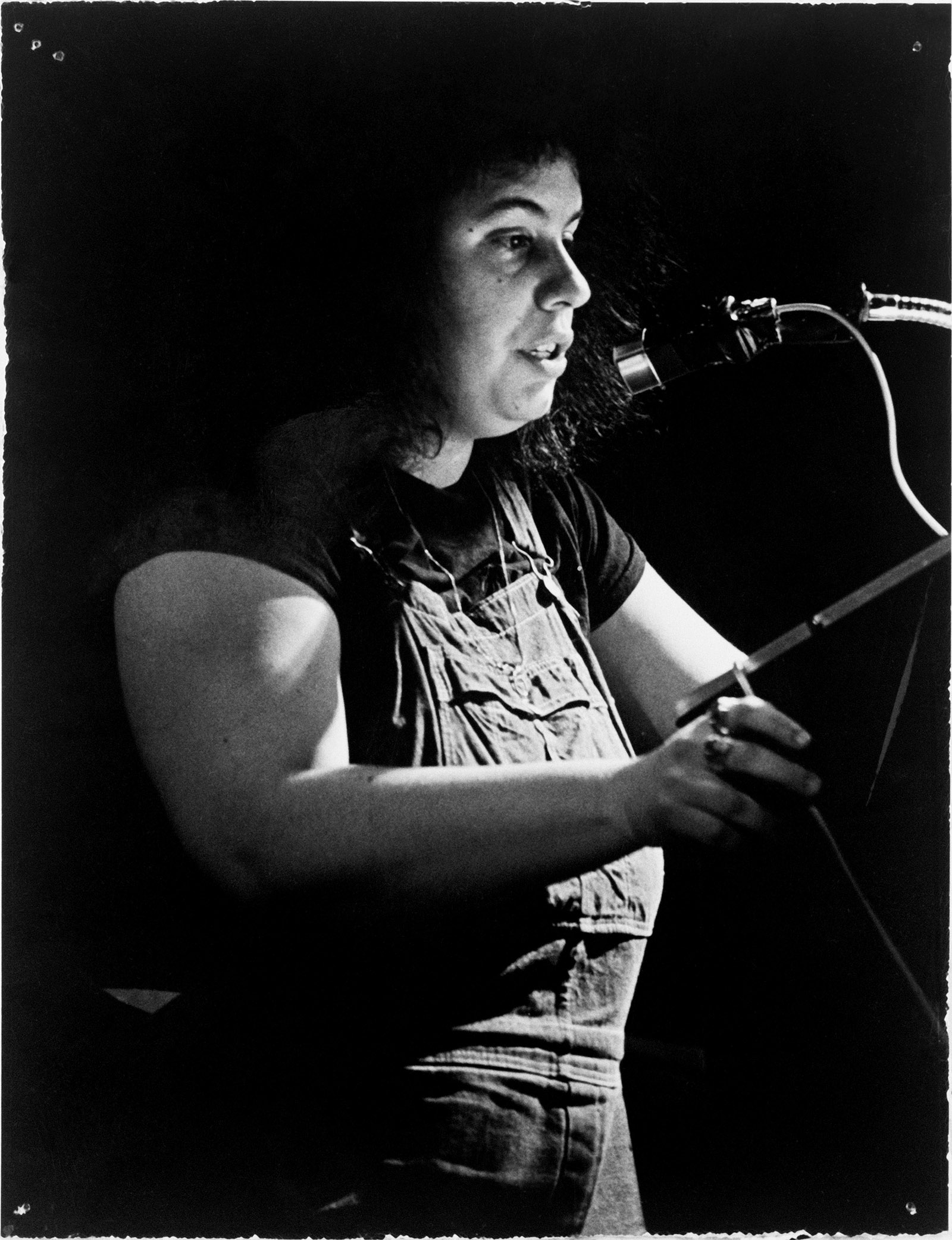

Andrea Dworkin found feminism in 1971, while she was on the run from her violent ex-husband, sleeping on friends’ floors and moving frequently to evade his stalking. She had married at twenty-two, to a fellow New Left countercultural activist from the Netherlands, and moved to Amsterdam to live with him. Soon after they married he began beating her. The first incident seemed like it must have been some kind of mistake. Domestic violence had not been a part of Dworkin’s childhood, and she knew nothing about it. “At the time, so far as I knew, I was the only person this had ever happened to,” Dworkin writes in a haunting 1995 essay called “My Life as a Writer.” After two and a half years of beatings, rape, and other physical attacks, she fled for good. A friend helped her find new places to stay along the way: houseboats, an abandoned mansion, a hippie commune on a farm outside Amsterdam. “In one emergency, [after] my husband had broken into where I was living, had beaten me and threatened to kill me, I spent three weeks sleeping in a movie theater that was empty most of the time.”

Dworkin’s friend brought her some recent books coming out of the American radical feminist movement: Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, and the anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful. Dworkin, who had left the US in 1968, had not heard of them. Like many in the New Left, she resisted their arguments at first: “Oppression meant the US in Vietnam, or apartheid in South Africa, or legal segregation in the US. Even though I had been tortured and was fighting for my life, I could not see women, or myself as a woman, as having political significance.” But there was one aspect of her recent experience that eventually made her receptive to the arguments:

I had been told by everyone I asked for help the many times I tried to escape—strangers and friends—that he would not be hitting me if I didn’t like it or want it. I rejected this outright. Even back then, the experience of being battered was recognizably impersonal to me. Maybe I was the only person in the world this had ever happened to, but I knew it had nothing to do with me as an individual.

Her intuition that the violence was impersonal opened the door to a feminist reading of domestic battery (and its tacit social acceptance) as a heavily gendered phenomenon, one of several kinds of violence that help maintain women’s social, legal, and financial subordination to men. Having seen the feminists’ point, Dworkin became severely disillusioned with the Left for its slowness to recognize female subordination as an injustice. While still on the run from her husband, she began to research and write her own contribution to radical feminist literature, Woman Hating (1974), a study of misogyny, in which she sifts through fairy tales and literary erotica, as well as the practices of European witch burning and Chinese foot binding. Like other second wave radical books that followed Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Woman Hating is enormous in scope, combining literary criticism with historical analysis and a theory of the origins and daily function of women’s oppression. But don’t mistake it—Dworkin insists—for a work of scholarly contemplation:

This book is an action, a political action where revolution is the goal. It has no other purpose. It is not cerebral wisdom, or academic horseshit, or ideas carved in granite or destined for immortality. It is part of a process and its context is change.

In these first four sentences of Woman Hating, Dworkin displays what her elders would have called a bad attitude: an anti-institutional, anti-establishment tendency expressed in profanity-laced, strongly declarative prose. She was inspired by the New Left and the Black Panthers, but “horseshit” is a degree cruder than anything in the Port Huron Statement or the writing of Huey Newton. She was from a lower-middle-class Jewish family from Camden, New Jersey, and had grown up reading Baudelaire and Rimbaud, Henry Miller and Allen Ginsberg at the bookstore in her local mall. A high school teacher who introduced her to Sartre and Camus also suggested she become a prostitute—“as he put it, it was more interesting than becoming a hairdresser, which was the one profession in his view open to women of my social class.” In fact, traveling in Europe during her college years, she had turned tricks when she ran out of money. She wasn’t taking the advice of lecherous older men any longer: “We want to destroy the structure of culture as we know it, its art, its churches, its laws: all of the images, institutions, and structural mental sets which define women as hot wet fuck tubes, hot slits.”

Advertisement

But it wasn’t all destruction; like her fellow radical authors, Dworkin also put forward a vision of what a nonsexist society might look like. For her, it was a world without gender polarity. There’s plenty of evidence, she argues, suggesting that male and female are not two cleanly separate and opposed categories: the existence of intersex people, essential similarities in male and female genitals, and variation among men and among women in gender expression. “The words ‘male’ and ‘female,’ ‘man’ and ‘woman,’” she writes, “are used only because as yet there are no others.”

“Andrea you are so prescient,” someone has written in the margin of my public library copy of Woman Hating, next to this sentence about our limited vocabulary for sex and gender differences. That seems to be the general critical consensus about Dworkin right now, though less because of her little-known early ideas about gender and sex fluidity, which she didn’t pursue in her later writing, than because of her lifelong focus on sexual violence. Dworkin was of course not the only radical feminist to write about rape and battery. Drawing on Marxist analysis, the radicals were distinct from the liberal wing of the movement for having ready theories of how violence and the tacit threat of violence enforces supposedly natural gender roles. Sexual Politics, The Dialectic of Sex, Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will, and Angela Davis’s Women, Race, and Class all include discussions of rape and other violence against women (Brownmiller’s book focuses on it exclusively). What Dworkin brought to the scene was, depending on your view of her rhetoric, either a bolder militancy or a greater tendentiousness.

By all means, decide for yourself: Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder have edited an excellent new collection, which includes excerpts of Dworkin’s fiction and nonfiction books, speeches, essays, and unpublished autobiographical writing. Dworkin called violence against women “an atrocity…being waged against us.” She derided what she considered the superficial 1970s vogue for men getting in touch with their feminine side: “Men who want to support women in our struggle for freedom and justice should understand that it is not terrifically important to us that they learn to cry; it is important to us that they stop the crimes of violence against us.”

Those lines are from a speech she wrote in 1975, “The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door.” After she would give the speech, some of the women in the audience would inevitably tell her about their own experiences of rape, so that she became a repository of stories about sexual brutality. Dworkin lived a version of Me Too decades before Me Too: she heard hundreds of accounts of women being assaulted. Echoing Dworkin’s own experiences, the stories affirmed for her that sexual assault was widespread and common, most of it committed not by strangers but by acquaintances, intimate partners, coworkers, and bosses—“normal men,” as she emphasized in speeches, respected elders of the community, or perhaps “the boy next door.”

“Dworkin, so profoundly out of fashion just a few years ago, suddenly seems prophetic,” wrote the New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg earlier this year. She quotes the following sentence from a speech of Dworkin’s:

Our enemies—rapists and their defenders—not only go unpunished; they remain influential arbiters of morality; they have high and esteemed places in the society; they are priests, lawyers, judges, lawmakers, politicians, doctors, artists, corporation executives, psychiatrists and teachers.

Goldberg writes that since “Trump’s election, the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, and revelations of predation by men including Roger Ailes, Harvey Weinstein, Les Moonves, Larry Nassar and countless figures in the Catholic Church, [Dworkin’s] words seem frighteningly perceptive.”

In at least one respect, we all now live in Dworkin’s world: we have scores of women’s testimony of assault and harassment ringing in our ears. As we hear teachers, lawyers, journalists, prison guards, waitresses, soldiers, actors, soccer players, state senators, nuns, and many other workers around the world describe forced sex acts on the job, it seems that Dworkin was on to the scope of the problem decades before we as a public were ready to take it seriously.

But can we assess Dworkin’s prescience without looking at the work that made her famous—namely Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981) and her part in the feminist anti-pornography movement? Recent critics have bracketed this part of Dworkin’s career—she had “inflexible views on pornography” that made her unpopular, Moira Donegan writes in Bookforum; Jennifer Szalai, in The New York Times, calls her position against pornography “extreme,” but notes that “such categorical edicts were what Dworkin became known (and lampooned) for, though they also happened to be the least interesting aspect of her work.” In a sense I agree, though what’s striking to me is precisely how little traction Dworkin’s analysis of pornography seems to have, given that we live in an era when people regularly express concern about its abundance online (some significant percentage of it depicting violence) and its potentially negative effects on personal relationships. We know that second wave feminism split over the issue and that pornography ended up with many more friends and defenders once Dworkin was through with it. Now, in a body of work that seems newly relevant, her writing about pornography stands out for having been unredeemed. What makes it irredeemable?

Advertisement

Dworkin did not love pornography. I don’t mean this as comic understatement of her well-publicized, steadfast opposition to it and of her attempts, with legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, to pass ordinances in numerous cities that would allow women to sue pornographers for damages. What I mean to draw attention to is that she devoted an entire book and part of another book (Woman Hating) to the close scrutiny of something she did not love or like. Of course you would hardly expect an activist fighting rape and battery to like those things: you would expect her to write about them out of a commitment to trying to stop them. But Dworkin’s involvement with pornography is a little different.

After she escaped her husband, Dworkin vowed that “I would use everything I know in behalf of women’s liberation,” and she did—she spent much of the rest of her life writing books, giving speeches, and appearing on panels to talk about sexual violence. But what kind of writing is it that Dworkin did? She was not a journalist; though she spoke to many women informally about their experiences, she was not reporting their stories, nor was she reporting on law enforcement or other aspects of sexual violence. She was not writing history, legal briefs, white papers, or sociological scholarship on women and violence.

What Dworkin wrote was cultural criticism. Despite her occasional potshots at academics and “effete” intellectuals, she arrived at much of her feminist analysis by studying texts. She wrote about pornography as a critic, studying the composition of its images, the themes of its fictional stories, its relationship to cultural myths and ideas. In this, Dworkin was pioneering. No less a sex-positive cultural force than Susie Bright—columnist, sex expert, author and anthologizer of erotica—praised Dworkin soon after she died in 2005 in an obituary she published on her blog. “Every erotic-feminist-bad-girl-and-proud-of-it-stiletto-shitkicker, was once a fan of Andrea Dworkin,” she writes. “She was the one who got us looking at porn with a critical eye.”

Like a lot of her contemporary critics and academics, Dworkin was looking both high and low, at fiction as well as nonfiction: in her investigation of pornography, she writes about the work of Sade and his biographers; The Story of O; Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye; the countercultural sex magazine Suck; gendered theories of sadism and masochism in the work of Havelock Ellis, Bruno Bettelheim, and Alfred Kinsey; and many different kinds of commercial pornography—Playboy, Mom (featuring pregnant models), stroke books, and more. The industry was in a period of expansion, and adult entertainment in all forms was newly visible. Dworkin reckoned that in order to fight an ascendant force like commercial pornography (and the larger forces of male supremacy), she would have to go big:

I would have to write a prose more terrifying than rape, more abject than torture, more insistent and destabilizing than battery, more desolate than prostitution, more invasive than incest, more filled with threat and aggression than pornography.

The result—her terrifying, insistent, destabilizing, desolate, and invasive rhetoric—is in uneasy tension with her searching impulses as a critic.

Pornography, Dworkin argued, was not only a kind of propaganda for male sexual domination but also “evidence and documentation of crimes against women.” The violence and humiliation depicted in pornography was “real,” she said—meaning not just that it represented the kinds of violence that actually happened to women in the world but that each photograph showed us a crime scene, each model was a woman being tortured at the time the photograph was taken. Nothing was staged, or if it was staged the model had not really been free to consent to it. Nothing was fake—unless the woman in the photo seemed to be enjoying the action, in which case that was definitely fake. Pornography is both a treacherous lie and the horrifying truth, as she writes in an introduction to Pornography:

A living archive, commercially alive, carnivorous in its use of women, saturating the environment of daily life, explosive and expanding, vital because it was synonymous with sex for the men who made it and the men who used it—men so arrogant in their power over us that they published the pictures of what they did to us, how they used us, expecting submission from us, compliance; we were supposed to follow the orders implicit in the pictures.

One of Dworkin’s main points is that pornography of all kinds, whether Playboy’s or Bataille’s, tells its readers that women are essentially submissive and masochistic, and like to have their will overridden in sex. The idea of natural female masochism, Dworkin notes, is woven through the work of psychoanalysts, psychologists, and naturalists, as well as imaginative literature, art, and popular culture. But Dworkin sources this view to pornography. She calls this idea the heart of “pornography’s values”—it is “what pornography says about women,” and men buy it, in both senses of the word:

Women, for centuries not having access to pornography and now unable to bear looking at the muck on the supermarket shelves, are astonished. Women do not believe that men believe what pornography says about women. But they do. From the worst to the best of them, they do.

Dworkin’s point is not to demystify pornography but to aggrandize it; she makes its consumption (by men you know!) seem terrifying rather than mildly embarrassing and disreputable. Her political writing has a strain of the melodramatic tension of Gothic fiction, in which we experience intimately the heroine’s discovery that the people closest to her can’t be trusted, that she has been lied to, that she is pitted against forces far more powerful than she is. There is, of course, a grain of truth here about feminist consciousness itself, in that it often entails the recognition that some of one’s closest intimates—fathers, brothers, husbands—are arrayed on the opposing side of a system of social oppression. Dworkin maximally exploits the deranging jolt of this discovery in Pornography, aided by the sensationalism of some of the pornographic images themselves.

What’s remarkable is that even with some very damning material in hand, Dworkin still has to sweat to characterize pornography as wholly aligned with the operations of male domination. She describes the plots of three stroke books (Whip Chick, I Love a Laddie, and Black Fashion Model) scene by scene in their entirety, then interprets them (“Pete’s final fate—to be fucked by his wife in the ass with a dildo until death do them part—is foreshadowed by the homosexual pleasure he experiences with the bum Cora set upon him in the motel”). Dworkin is interested exclusively in the books’ celebration of phallic power and contempt for women and femininity, and she finds plenty of supporting evidence. But even in these books, handpicked by Dworkin for polemical purposes, there seems more going on than her narrow reading allows. Or, to put it another way, if Pete’s enthusiasm for being ass-fucked by his dildo-wielding wife is an item of propaganda for patriarchy, then patriarchy is a subtle foe, against which we need still more subtle criticism.

When Dworkin figures pornography as a “carnivorous” and “expanding” force, she’s talking about the products for sale, whose number was certainly expanding. But pornography expands in another way: culturally. Its tropes come loose from the commercial products or underground publications and appear in literature, journalism, public discourse—and feminist polemic. Dworkin, after all, painstakingly describes for us not only three dirty books but countless dirty pictures: she brings pornography into Pornography.

Look again at the passage about women encountering porn on the supermarket shelves and note the state of psychic conflict implied in Dworkin’s phrase about women: it’s not that women don’t like the porn or don’t want to see it at the supermarket, it’s that they can’t bring themselves to look. Why can’t they bring themselves? Because they will be horrified—or aroused? Is it that they feel like they should look but really don’t want to, or that they fear once they start looking they might not stop? The very ambiguity of the scene suddenly seems dirty, and of course a woman wanting and not wanting to look is a pornographic mainstay, as is almost every possible response a woman (or a vice cop) could have to pornography: curiosity, surprise, arousal, disgust, anger, indignation, or all of the above. Dworkin thinks she’s got pornography’s number, but the reverse seems true. Her sentences become lurid under its influence.

If you had to name one underlying reason that pornography threatens to get the better of Pornography, it’s because the book does not admit the possibility that its readers might have an erotic response to the subject. Maybe it never occurred to Dworkin that readers could feel that way, or maybe she considered it frivolous and immaterial: we’re here to fight male domination; your sexual excitement is your own little problem. Maybe there’s a touch of hostility in her piling on detail after pornographic detail, challenging her reader to maintain a stance of solemn political commitment as she closely follows the action of Scott and Pete and Cora and Cora’s dildo, which Alice fears is too big.

Dworkin had never gone in for female-sexuality boosterism. Time enough for all that after the revolution was her basic attitude. In a speech she delivered at the National Organization for Women’s conference on sexuality in 1974, she quotes a passage from the diary of Sophie Tolstoy about the miseries of her marriage to Leo, which ends with the following lines:

I want nothing but his love and sympathy, and he won’t give it to me; and all my pride is trampled in the mud; I am nothing but a miserable crushed worm, whom no one wants, whom no one loves, a useless creature with morning sickness, and a big belly, two rotten teeth, and a bad temper, a battered sense of dignity, and a love which nobody wants and which nearly drives me insane.

What advice would you give this woman if she were here among us, Dworkin asks the crowd: “Would you have handed her a vibrator and taught her how to use it?”

It’s a great line—but what makes it work? It’s easy to make the pursuit of sexual pleasure seem trifling, especially when held up against the enormity of women’s oppression. In Dworkin’s critical writing, sex is trifling unless someone is being harmed by it. Rape and rape-adjacent acts are the only kind of sexual pursuit that she takes seriously, and it’s only men’s sexuality that has any importance; to her way of thinking, sexuality is male (“men own the sex act, the language which describes sex, the women whom they objectify”). She doesn’t find much of interest in the fact—the problem? the complication? the loophole?—that women can be sexually attracted to men, or to women, or to anyone in between. Even more significant is her denial—the unacknowledged bedrock of Pornography—that women, like anyone else, can be perverse.

Dworkin’s world is a lonely place for the reader who can bring herself to look, and the loneliness is not trivial: it’s why many feminists ultimately dissented from the anti-pornography movement, defended BDSM, and made their own pornography. “Anyone who thinks women are simply indifferent to pornography has never watched a bunch of adolescent girls pass around a trashy novel,” wrote Ellen Willis in The Village Voice as she led a break-away “pro-sex” movement of the second wave. “The last thing women need is more sexual shame, guilt, and hypocrisy—this time served up as feminism.”

The groundbreaking Barnard Conference on Sexuality was organized in 1982 as a rebuttal to the feminist antipornography movement. In her highly influential essay “Thinking Sex,” Gayle Rubin pointed out the fact (so starkly evident in Pornography) that feminism was operating without any theory of sexuality beyond its being a potential tool of women’s oppression by men. As a result, feminists, like traditionalists, tended to draw lines between so-called good and bad sexual practices, with sexual minorities liable to end up on everyone’s bad list and subjected to ostracism and violence as a result.

Dworkin held firm on her anti-pornography position as critics, feminist and otherwise, picked apart her arguments, and as pornographers, notably the publishers of Playboy and Hustler, derided her in the press (and in their pages: Hustler published a sexually explicit cartoon of her, in response to which Dworkin unsuccessfully sued the magazine). But her last major work of feminist criticism, published in 1987, was notably different in tone and scope from Pornography. Intercourse looks at the cultural meanings of heterosexual vaginal intercourse and at the political consequences of understanding women’s bodies as necessarily and rightly permeable. Of course, everyone’s body is sexually permeable (just ask Whip Chick’s Pete), but we divide the world into “the fucker and the fucked,” Dworkin argues, and in that schema women are the preeminent exemplars of the fucked: weak, compromised losers.

Nowhere in the book does Dworkin call to ban anything or to change anyone’s behavior. And, notably, rather than going after a disreputable perversion, she is here going after—denaturalizing—the fountainhead of male heterosexual domination. Intercourse is, broadly speaking, a queering project. Could Dworkin have been influenced by feminist critics of Pornography? She certainly doesn’t say so (in her version of events, she has not been wrong since the early 1970s) and she is more likely to have been influenced by MacKinnon’s writing on the role of sex in female subordination. But Intercourse seems to mark a tactical shift. It is also Dworkin’s bleakest book. One reason she doesn’t suggest we change any behaviors is because there’s no way out: practice intercourse or don’t, like men or don’t—if you’re a female walking around in this world, you can’t free yourself from intercourse’s misogynistic associations. With Intercourse, Dworkin can seem, in her inimitable way, to be saying to her critics both point taken, and fuck you.

This Issue

June 27, 2019

Reckless in Riyadh

Africa’s Lost Kingdoms