Cities dominate cultural life and the economy no less today than they have for centuries. They are still the principal centers of intellectual ferment, artistic creativity, and social innovation despite the decentralizing potential of the Internet. In fact, while rural areas and small towns have been stagnant and declining in recent decades, economic growth has become even more concentrated in large cities that can satisfy the demand for highly educated workers. If political power simply followed economic dynamism, the surging metropolises of the global economy—like cities at the heart of empires and nations in the past—would now be the dominant force in government.

But the reality in the United States is exactly the opposite. As Jonathan Rodden explains in Why Cities Lose, urban interests are systemically underrepresented in state legislatures and Congress. With Democrats clustered in cities, Republicans often win legislative majorities despite losing the overall popular vote. Conservative parties benefit from the same pattern in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, where the left’s vote is also concentrated in cities. There, too, conservatives tend to win a larger share of legislative seats than of votes, sometimes enough to form a government even though the main opposition party has won more votes. The reasons why cities lose are therefore often the reasons why the left loses too.

Democrats are painfully aware that they face institutional disadvantages in American politics. Republicans have won the presidency in the Electoral College twice in the past two decades despite losing the popular vote. Since the Senate overrepresents rural, relatively conservative states, it too now favors Republicans: “Democrats have won more votes than Republicans in elections for eleven of the fifteen Senates since 1990,” Rodden notes, “but they have only held a majority of seats on six occasions.”

What is less widely understood is that Democrats also face a structural disadvantage in the House of Representatives and many state legislatures. In 2012, despite receiving 1.4 million more votes in House races than Republicans, Democrats won only 45 percent of House seats; that same year, Democratic candidates in Michigan received 54 percent of the vote but only 46 percent of the seats in the Michigan house and 42 percent in the state senate. The conventional explanation for these and other disparities is partisan gerrymandering, which unquestionably has exacerbated the Democrats’ problems since 2010, when Republicans won control of many state legislatures and then redrew district lines in their own favor.

Rodden, a political scientist at Stanford, shows convincingly, however, that Democrats would be at a disadvantage even if partisan gerrymandering were abolished. Neutral computer simulations still tend to give Democrats a smaller share of seats than Republicans would receive with the same share of votes. The Democrats’ underlying problem, he argues, results from two factors: an increased urban-rural divide in voting and the use of single-member districts in US legislative elections—the same method used in Great Britain and others of its former colonies.

Although an urban-rural political divide exists today in many societies, its effects depend on the system of representation—that is, the rules for turning votes into seats. Under systems of proportional representation, each party gets a share of seats in large multimember districts in accordance with its share of votes, no matter where those votes come from. The geography of partisan support matters a great deal, however, in countries using single-member districts that are winner-take-all: “Underrepresentation of the urban left in national legislatures and governments,” Rodden writes, “has been a basic feature of all industrialized countries that use winner-take-all elections.”

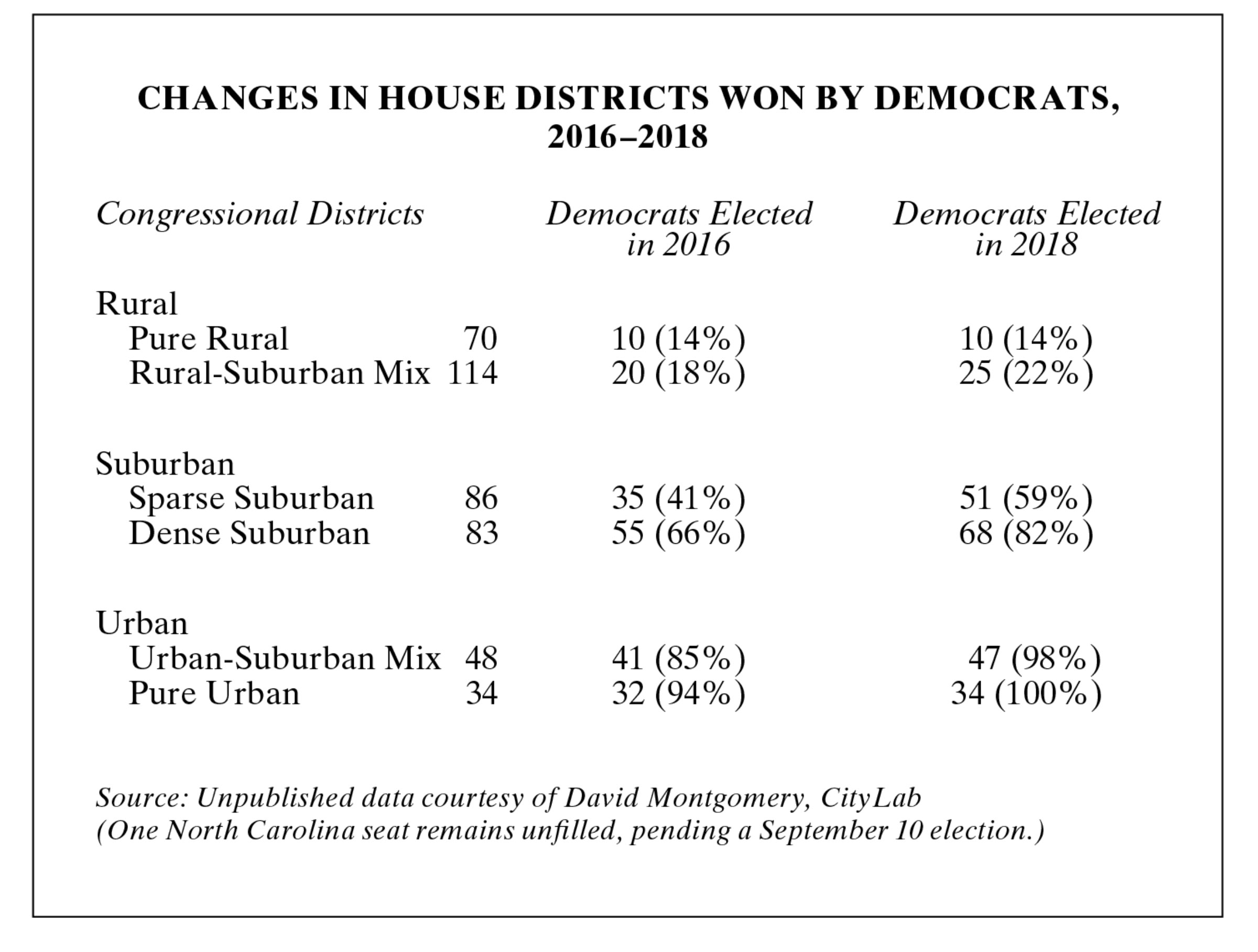

Electoral disadvantage does not necessarily mean defeat. Democrats were able to win control of the House in 2018, when they received an overall margin of more than 8 percent of the popular vote. Where those votes came from was critical. Although Democrats increased their share of votes everywhere, they already held nearly all urban districts, and their improved showing in rural areas wasn’t enough to win many seats there. What made the difference was a blue wave in the suburbs strong enough to lift Democratic candidates to victory. As data from CityLab show (see table below), nearly three quarters of the Democrats’ net gains in the House (twenty-nine of forty seats) came in suburban districts, and there was virtually no shift in districts that were either “pure rural” or “pure urban.”

The striking contrast in the Democrats’ current share of seats from 14 percent in pure rural to 100 percent in pure urban districts highlights a central theme of Rodden’s book: population density now predicts partisanship. Indeed, partisan conflict is now so sharply polarized on urban-rural lines that in state capitals as well as Congress, cities are almost exclusively represented by Democrats; consequently, when Republicans are in power, cities are usually shut out of political influence. And since the Electoral College, representation in the Senate, and the electoral system for the House and state legislatures all disadvantage Democrats, the cities have lately been shut out very frequently.

Advertisement

Why Cities Lose explains how urban underrepresentation developed historically, how it varies from one region to another, and how it has shaped politics in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia. Rodden’s analysis is particularly useful for understanding the choices facing today’s urban-based parties of the left, including the Democrats, as they try to overcome entrenched disadvantages.

In the United States, the emergence of a sharp urban-rural divide on a national scale is comparatively recent, chiefly because of the Democratic Party’s historical support in the South. As a coalition that included rural white southerners as well as populist farmers in the West, Democrats were stronger in rural areas than in cities in the late 1800s and early 1900s. By the 1930s, they had become an urban party in the northern industrial states. But even after losing the white South to the Republicans in presidential elections beginning in 1964, the party held onto much of its rural base in Congress and state legislatures. From the 1960s to the 1980s, many Democrats were able to keep getting elected by distancing themselves from the national party. When Boston’s Democratic congressman Tip O’Neill famously said “All politics is local,” he was describing the politics that kept Democrats in the House majority and made him Speaker from 1977 to 1987.

That era ended in the 1990s, when Republicans under Newt Gingrich successfully “nationalized” congressional elections and gained control of the House. By that time, the Democrats had become identified with progressive positions not only on race and civil rights but also on such issues as abortion and sexuality. “Voters’ preferences on these issues,” Rodden notes, “are highly correlated with population density.” Rural social conservatism is an old phenomenon; what is new is the sharp polarization between the parties on cultural issues. Republicans, who had been somewhat more pro-choice than Democrats in the 1970s, turned entirely against abortion, while Democrats championed women’s equality and LGBTQ rights. The more salient those social issues became in elections, the more voters in urban and rural areas sorted themselves on that basis into the two major parties. The urban-rural partisan divide, long a phenomenon in the industrial states, had now become the principal axis of partisan conflict throughout the country.

But the origins of the urban-rural political divide in the United States, Britain, and the Commonwealth countries go back earlier. In Rodden’s account, they lie in the industrializing cities of the nineteenth century, which developed a characteristic political form that has outlasted its original causes. To minimize transportation costs, factories were located in the urban core in close proximity to water and rail connections for shipping, while workers lived nearby in the dense, cramped housing that was built for them. Suburbs for the more affluent grew even before the advent of the automobile, but they were out of reach for industrial workers.

The political geography of cities followed their economic geography. Parties of the left—originally socialist and labor parties in many countries, later the Democrats during the New Deal—organized workers in the urban core, while conservative parties dominated areas further from city centers. Remarkably, while the economies of cities have changed, their political geography has persisted. When manufacturing departed, the old neighborhoods filled up with the poor and minorities, immigrants, and sometimes students and artists—and they too supported the parties of the left.

The result is a paradoxical relationship of the left to industry and industrial workers. Democratic votes today, Rodden shows, are geographically correlated with manufacturing employment a century ago, while Republican votes are correlated with contemporary manufacturing. “Today,” he writes, “the Democrats are the party of urban, postindustrial America, and the Republicans receive more votes in exurban and rural places where manufacturing activity still takes place.”

States and metropolitan areas vary in their political geography, depending mainly on their economic history. In some states that developed a single major city in the industrial era—for example, Chicago in Illinois—Democrats are mainly clustered in one large enclave, while in states like Connecticut and Ohio that now have several postindustrial cities of varying size, Democrats are more dispersed in a series of clusters. In those postindustrial cities, the Republican vote rises sharply as one moves out from the urban core; the Trump vote in 2016, Rodden shows, rose from about 20 percent in the city centers to more than 60 percent in the exurbs of Ohio and Pennsylvania. But in cities that have become major hubs of the information economy such as Boston and Seattle, the college-educated population is larger and spreads beyond the city, and the falloff in the Democratic vote in the suburbs is lower. The sprawling cities of the Southwest that developed in the age of the automobile also have less of a contrast in voting between the core and periphery, because they didn’t develop around an industrial core. Despite these variations, Rodden writes, “American cities are, for the most part, dense clusters of Democrats surrounded by sparser Republicans.”

Advertisement

What disadvantages Democrats politically is not that they live in cities but that they are so densely clustered in them. Cities are socially diverse, but politically they are relatively homogeneous; Democrats run up huge majorities in urban districts, “wasting” large numbers of votes. Nonurban districts are more politically heterogeneous; even many rural areas dominated by Republicans have Democratic islands such as college towns and small cities. In Rodden’s words, both Democrats and Republicans tend to “live among their own kind,” but there is an “asymmetry to their segregation” at the geographic scale relevant for state and congressional districts. Democrats are underrepresented in legislatures because they are “inefficiently” concentrated in politically homogeneous communities.

Republicans are overrepresented in legislatures in nearly all states, except those that are already overwhelmingly Republican. The clearest examples of that overrepresentation are Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina—states where Republicans have had perennial majorities in the state legislatures even though the two parties are closely matched in statewide races. In all but two of these states, Rodden argues, the Republicans would still have a geographic advantage without gerrymandering; the exceptions are Ohio and North Carolina, where Democrats are widely dispersed and Republicans have needed gerrymandering to maintain control. In other states, Republicans have been able to use gerrymandering to magnify the advantage that the geographical distribution of Democratic votes already gives them.

Democrats have understandably made partisan gerrymandering a major target of criticism; with the aid of sophisticated software, Republican gerrymanders have reached unprecedented levels in the past decade. Although the Supreme Court in late June refused to declare partisan gerrymanders unconstitutional, it left the issue to the states. On the basis of its state constitution, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned the Republican gerrymander in that state in time for the 2018 election. Independent redistricting commissions are a popular reform with voters, and several states have instituted them, including Michigan in 2018 in a referendum.

Rodden’s book is not an argument against such commissions but rather a caution about how much they will be able to accomplish. Other countries with British-style single-member, winner-take-all districts already have nonpartisan redistricting, but their legislatures still underrepresent urban-based parties of the left. Even in the unlikely event that Democrats could legislate the creation of independent commissions for all states, they would still win fewer seats than their share of votes.

What is to be done? Democrats have two options—one that is admittedly a long shot, and another that is more practical but necessarily comes with compromises.

The long shot is to try to get individual states, and perhaps ultimately the US House, to adopt proportional representation. Change in electoral methods is usually difficult for the obvious reason that the winning parties typically don’t want to alter the rules that enable them to win. In a two-party system, even the disadvantaged party has incumbents in safe seats who benefit from the status quo. Since proportional representation would likely help third parties, the two major parties’ leaders may share an interest in keeping the system the way it is.

Unsurprisingly, the support for proportional representation in countries with winner-take-all elections has mainly come from third parties, such as Britain’s Liberal Democrats and Canada’s New Democratic Party. Even third parties that have advocated proportional representation do not necessarily stick with it once they start winning. For example, the Labour Party in Britain supported proportional representation until it displaced the Liberals as one of the country’s two major parties in the 1920s, at which point it reneged. Still, a shift to proportional representation is not impossible. New Zealand made the change in 1996 as a result of a referendum. If the United States is to see any movement toward proportional representation, it would most likely be through a referendum at the state level.

The system that New Zealanders adopted is a hybrid form known as “mixed member proportional representation,” in which voters cast one vote for an individual candidate in a single-member district and a second for a political party. The legislature then consists of the winners in individual districts and at-large representatives from the parties distributed among them to give each party its proportional share of total seats. The system has long been used in Germany, where it is called “personalized proportional representation” because it achieves proportionality while preserving a valued feature of single-member districts—the voters’ sense that they have a personal representative in the legislature.

Since the mixed-member system preserves individual district elections, it is less of a radical innovation for voters, and perhaps less threatening to incumbents, than a system of proportional representation drawn strictly from party lists. The Constitution does not require the exclusive use of single-member districts for the House; the current system is a matter of federal statute. Although any change in congressional elections would require action by Congress, states could adopt a different method for their legislatures. But as long as Democrats and independents mistakenly see gerrymandering as the entire problem, they are unlikely to give an unfamiliar alternative serious consideration.

Since the road to proportional representation is at best a very long one, the more immediate option for Democrats is to follow the same strategy they used in 2018: pursuing gains in the suburbs. But a strategy focused on the suburbs will come at a cost.

In a 1992 article in The Atlantic, the political analyst William Schneider noted that, based on the census two years earlier, suburbanites were about to become a majority of the US population for the first time.1 Not only had the suburban vote been growing; Republicans over the previous three decades had taken an increasing share of it. The suburbanization of American politics, Schneider argued, posed an enormous problem for Democrats. Suburbanites saw themselves as property owners and taxpayers who not only bought private homes and yards but also “bought” limited government. “To move to the suburbs,” Schneider wrote, “is to express a preference for the private over the public.” If Democrats were to win in the suburbs, they would have to adjust their policies accordingly. From the 1990s until 2018, Democrats were able to make some gains by nominating moderates, but Republicans continued to dominate the suburbs and growing exurbs.

Some progressives have suggested that it is self-defeating for Democrats to chase after affluent suburban districts. In June 2018 two left-leaning historians, Lily Geismer and Matthew D. Lassiter, warned Democrats that the strategy of nominating centrists in the suburbs had yielded only “modest” results. Moreover, they argued, “turning moderate and affluent suburbs blue” wasn’t worth the sacrifice of progressive goals: “Democrats cannot cater to white swing voters in affluent suburbs and also promote policies that fundamentally challenge income inequality, exclusionary zoning, housing segregation, school inequality, police brutality and mass incarceration.”2

If Democrats had followed that advice and decided that it was pointless to nominate moderates who could win in the suburbs, they wouldn’t control the House today. Geismer and Lassiter were right, however, about the basic dilemma. If the Democratic Party depends on affluent suburban districts, it will face limits on the legislation it can pass. But under the existing electoral system, it has little choice. In countries with proportional representation (and in statewide elections in the United States), an additional vote in cities or rural areas is just as valuable as an additional vote in the suburbs. But in congressional elections, the votes that matter most are the ones in swing districts, which in the United States are now nearly all in suburban areas.

The Democrats’ dependence on suburban votes is already constraining Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other House leaders. During the past several months, the media’s spotlight has been on the four urban progressives whom Pelosi calls “the Squad”—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib. Trump has made them the subject of venomous attacks and, he hopes, symbols of the Democratic Party. But the Democratic caucus in the House has actually shifted toward the center because of the addition of so many moderate suburban representatives. Democratic leaders know that if they are to keep their majority in 2020, they must protect those suburban moderates. As a result, they have kept Medicare for All and other issues pushed by the House’s Progressive Caucus from coming to the floor.

This kind of tension is typical of parties of the left in countries with British-style elections. Such parties, Rodden argues, are often so dominated by their urban representatives that “they find it difficult to craft a platform that will allow them to win in the crucial suburban constituencies.” If they depend on the suburbs to win a majority, they have to keep the urban left in check.

One new factor, however, may help the Democrats. In an age of populist reaction, the Republicans have moved farther from the center and are now so beholden to their exurban and rural representatives that they are running into troubles of their own in the suburbs. The center-right Republicans who used to win in those districts have been disappearing. By adopting the positions of social conservatives rooted in small-town and rural America, Trump and his party have increased the opportunity for Democrats to create a new center-left majority that brings together the cities and suburbs.

Whether Democrats can sustain their suburban gains will be one of the great questions of 2020. Even if they do, the geographic disadvantage from excessively clustered urban votes won’t go away, and they ought to look to more fundamental reforms than independent redistricting commissions. Proportional representation isn’t yet an idea that most reform-minded Americans have considered. Rodden’s Why Cities Lose should start people talking about it.

This Issue

September 26, 2019

Australia’s Shame

Brexit: Fools Rush Out

‘Ulysses’ on Trial