Over the past few years, the authorities in Beijing have given churches across the country orders to “Sinicize” their faith. According to detailed five-year plans formulated by both Catholic and Protestant organizations, much of this process involves the predictable palaver of state control: “to actively practice core values of socialism, love the motherland passionately, support the leadership of the Communist Party, obey the law and serve society.”1

But the authorities want more than just political control; they want a say over Christianity’s spirit, too. According to one document, “Chinese styles” are to be promoted in the religion’s “building, painting, music, and art,” and also in Christian liturgy and theology. Other documents speak of reflecting Chinese traditions, but what this means isn’t exactly clear—perhaps filial piety, ancestor worship, and explicitly rejecting foreign influence.

While these new regulations affect China’s other religions too, they hit each one in different ways. They probably matter least to Daoism, which is an indigenous Chinese religion, and little to Buddhism, which is a global religion but has been in China for so many centuries that it has spawned local schools and practices. But for China’s other two main religions, Islam and Christianity, the rules raise serious concerns. In the case of Islam, the state’s aim seems to be mainly political control of sensitive border regions, because of the faith’s predominance among several ethnic minorities, especially the Hui and the Uighurs, who live in China’s far west.

Christianity poses a subtler and possibly more profound challenge. This is not only because it has spread among the ethnic Chinese, or Han, majority, who make up 92 percent of China’s population, but also because it has grown fastest not in remote border regions but in the cultural heartland and among white-collar professionals who are supposed to be leading China’s modernization. This makes Christianity the first foreign religion to gain a central place in China since Buddhism’s arrival two millennia ago. Hence the authorities’ unease and their vague desire for Christianity to become something Chinese and nonthreatening.

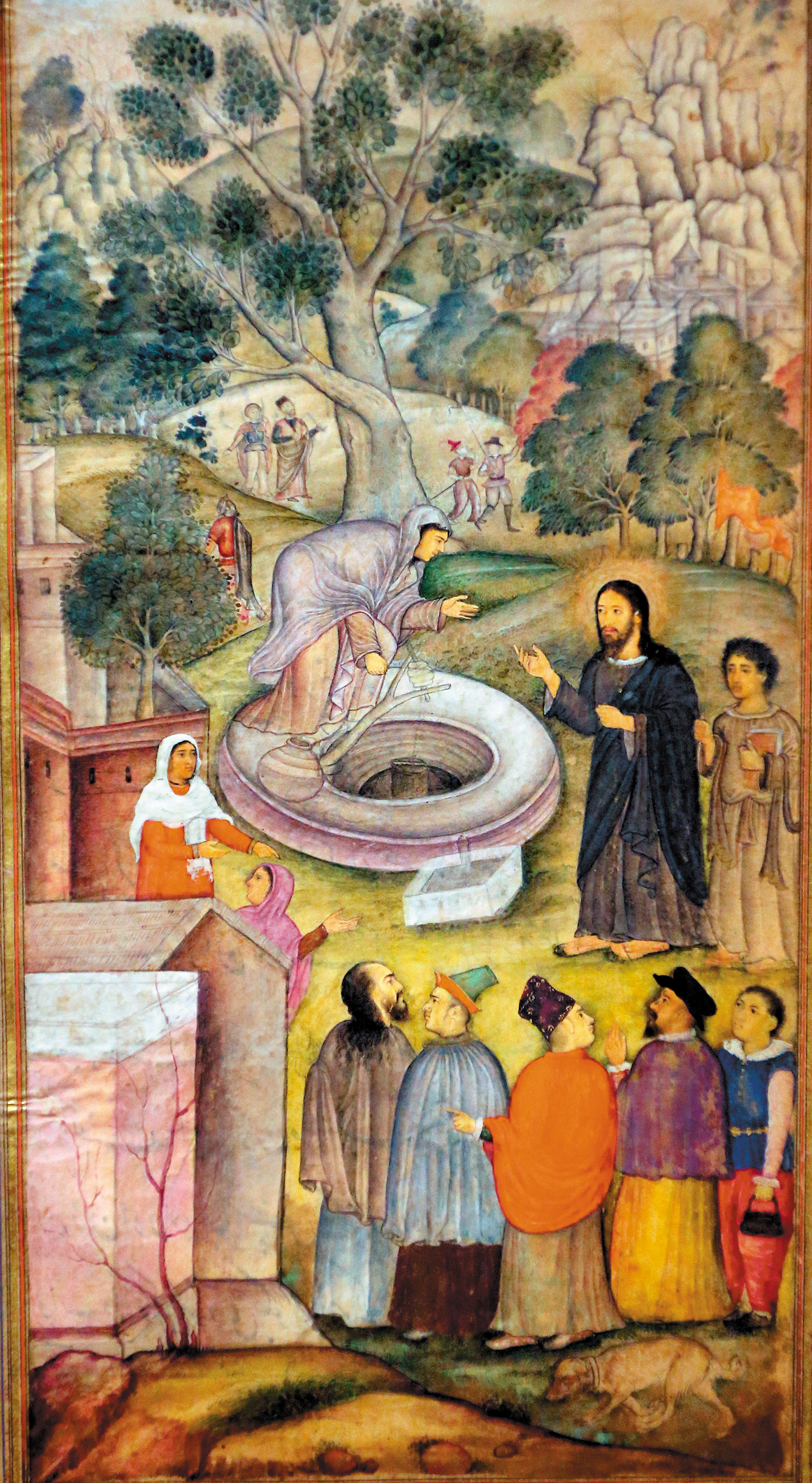

These concerns have arisen before. Christianity has had a presence in China for four hundred years. Missionaries such as the Jesuit Matteo Ricci got a foothold in the country by acting like Confucian officials: dressing in gowns, learning the formal language of classical Chinese, and downplaying differences between Christianity and Chinese thought. The Jesuits called God tianzhu, or “lord of heaven,” a plausible term for the Heavenly Father, but not coincidentally also the name of an old Chinese deity. Over the following decades, Christianity spread in North China by fitting into familiar folk religious patterns: offering moral precepts that sounded like Confucian principles or worshipping a virgin saint who seemed much like local female deities. Missionaries in this era, before imperialism made them arrogant, softened unfamiliar or disturbing ideas, such as Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection.2

The new effort to sinicize Christianity is something different—and probably unique in its encounter with Asia. In years past, Chinese and other Asian governments were weak, and even if Christianity found followers it was later tarnished by the fact that missionaries arrived along with Western gunboats. Now we have a strong government in Beijing that accepts the reality of Christianity but wants it to conform to Chinese foreign and domestic policy. This isn’t unusual in Christian history—look at the innumerable British churches with tableaux and plaques that glorify British imperialism—but Beijing’s firmness is something new in Asia.

In Jesus in Asia, R.S. Sugirtharajah recounts earlier Asian efforts to make sense of Christianity and to disentangle it from imperialism. Sugirtharajah, one of the foremost scholars of global Christianity, a Sri Lankan native and professor emeritus of biblical studies at the University of Birmingham, has written extensively about Christianity’s influence in the developing world. In this book, Sugirtharajah shows how Jesus has been promoted, despised, and utilized in Asia. He begins in China around the seventh century and ends in twentieth-century South Korea and Japan, but is mainly concerned with thinkers from the Indian subcontinent.

It is here that Sugirtharajah shines. He introduces us to intellectuals—some believers, many not—who grappled with Jesus as a historical figure and a person with a place in Asian religions. Most were not interested in academic searches for the historical Jesus—in other words, in textual analyses that might or might not prove that he existed, or the probability that he carried out certain acts. Instead, they examined the man and his message, comparing him with other religious figures, such as Zoroaster, Buddha, and Krishna.

Advertisement

Sugirtharajah discusses many memorable people, such as the Sri Lankan Hindu thinker Ponnambalam Ramanathan (1851–1930). Like many others featured in the book, Ramanathan was less interested in the flesh-and-blood Jesus than in his spirit. He lauded his childlike nature and ability to reveal God, writing, “Jesus found Christ within himself, and through the Christ within, he attained God.”

But Ramanathan was also irritated by the biblical accounts of Jesus’s lineage to King David, seeing them as a needless diversion to satisfy Jewish audiences. As for Jesus’s resurrection, Ramanathan dismissed it as a “vulgar doctrine,” arguing that it must be understood symbolically, not literally. Ramanathan wrote two books about Jesus and also went on a speaking tour of the United States, where he told audiences that Christian ideas, such as the kingdom of God being within oneself or neighborly love, are not originally Christian but the “old Hindu doctrine, and it has been brought to you by your own religious teacher, Jesus Christ.”

This illustrates one of Sugirtharajah’s main points: that Asians decolonized Jesus, often by making him into an Eastern mystic whose teachings were profound but nothing special, and indeed were often inferior to Asian traditions. This was achieved not through strict academic inquiry but a selective and sometimes polemical reading of the Bible, in which useful passages were accepted and others were dismissed or ignored.

These were methods used by C.T. Alahasundram (1873–1941), who took his paternal grandfather’s name, Francis Kingsbury. Kingsbury also wrote a book about Jesus that ruthlessly omitted events he thought were useless or unconvincing to a person from the subcontinent. So out with the nativity story, the genealogical links to King David, and Jesus’s temptation. Instead, Kingsbury thought Jesus was mainly significant for his ethical views, which he equated with those of Buddha.

This drawing of equivalences between Jesus and local religious figures was also the method used by one of the book’s most striking figures, the Jain convert Manilal Parekh (1885–1967), who saw Jesus as a Tirthankara—a savior and spiritual teacher in the Jain faith. Parekh tried to cleanse Christianity of European culture and imperialism, for example by dismissing its denominational differences as having been introduced by European missionaries. As Sugirtharajah puts it, “He saw his task as making Jesus suitable and intelligible to Indian spirituality.”

Thus in Parekh’s book A Hindu’s Portrait of Jesus Christ (1953), he tossed out the virgin birth—a strange event that he saw as irrelevant to Jesus’s importance—and Jesus’s uniqueness as the only son of God, a claim he thought exaggerated. He also found much of Jesus’s life unappealing, describing him as a villager from Palestine with a narrow worldview who seemed unaware that his country was occupied by Rome. His “mental horizon,” according to Parekh, seemed “confined entirely to the Jewish world.”

As for the miracles, they were commonplace among Hindu and Muslim healers on the subcontinent and so for Indians wouldn’t “add an iota to [Jesus’s] moral and spiritual greatness in their eyes.” As a Jain, Parekh also found fault in Jesus for eating meat, offering fish to hungry followers, and venting his anger at a tree, which he said showed him to be “unreasonable and unnecessarily petulant.”

This sort of appraisal of Jesus according to indigenous religious tenets is taken to its most extreme in the writings of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1885–1975), a philosopher-statesman who was perturbed by how Hinduism was denigrated by missionaries. He wrote of Jesus as being heavily influenced by Eastern, especially Buddhist, ideas—a not unreasonable claim, since Buddha’s writings predate Christianity and may have circulated in the Middle East around the time of Jesus. Radhakrishnan noted many parallels between Jesus and Buddha, including their miraculous births, selection of disciples who were then sent out on missions, close relations with women, triumphal returns into their native cities, and the earth’s quaking when they died. “Buddha and Jesus,” he wrote, “are men of the same brotherhood.”

These are some of the book’s most stimulating chapters, and I couldn’t help agreeing or at least sympathizing with many of these thinkers. The emphasis on Jesus’s lineage to King David always seemed to me a particularly desperate effort by the Gospel writers to make him fit Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah, while the story of Jesus’s physical resurrection—how he surprises Mary at the tomb and shows his scars to the disciples—was irrelevant and sort of kitschy. Surely what matters, as these writers pointed out again and again, is spiritual rebirth and immortality, not the raising of a corpse, as if Jesus were an Egyptian pharaoh.

Advertisement

I must, however, point out two main weaknesses. One is Sugirtharajah’s excessively apologetic tone toward his subjects. He notes that none of them used modern research criteria, such as comparing texts for coherence, corroboration, or multiple attestation. But Sugirtharajah unhelpfully calls these “criteria that Western scholars routinely employ,” when in fact they are common tools used by scholars of many cultural backgrounds. Instead, he says that the writers he discusses used “continental self-reference,” a term he does not define but that I pieced together from other works by him. It means that these people made sense of Jesus by comparing him to local holy men and their doctrines. This sort of jargon mars the book in several spots and in a way weakens the arguments of the writers—their methods of criticizing Jesus are perfectly valid and understandable without recourse to postcolonial academese.

More significant are flaws that crop up when Sugirtharajah leaves South Asia. He does have an excellent chapter on minjung Christianity, the South Korean movement pioneered by Ahn Byung Mu (1922–1996). Ahn rejected modern Western theology’s lack of interest in searching for the historical Jesus and its contentment with seeing him as an allegorical figure. Instead, Ahn demanded that his stories be taken seriously as real events. As an opponent of the South Korean military dictatorship, Ahn emphasized Jesus’s solidarity with the masses, or minjung in Korean, and the strength he drew from the ordinary people of Galilee.

Less successful are two of Sugirtharajah’s chapters on China. His first chapter recounts the story of the first Christians known to have arrived there, the Nestorians, or representatives of the Church of the East. These were people from modern-day Syria and Iran whose beliefs were declared to be heretical in the mid-fifth century. They reached China in the seventh century during the Tang dynasty, widely reckoned to be China’s most open and greatest dynasty, and were given the right to practice their teachings.

Sugirtharajah unfortunately relies heavily on Martin Palmer’s The Jesus Sutras (2001), a popular but unreliable book that translates in a very free fashion a famous Nestorian stele and eight documents found in the Dunhuang cave complex in northwest China. Palmer’s book elides these materials and claims that all of them have a Christian orientation, even though this is an overenthusiastic and generous reading. Palmer also seemed unaware that two of the texts he translated are widely considered to be forgeries.

Because Sugirtharajah relies heavily on these secondary sources, it’s hard to have confidence in his conclusions about that early Christian community. I found myself flipping back and forth to the endnotes, trying to figure out which of his claims I should discount. Adding to the confusion are unclear citations, which make it hard to know if Sugirtharajah is citing Palmer or other sources. It’s also flat-out incorrect to say, as Sugirtharajah does, that the Nestorian mission was “probably the last time that Christianity and Eastern religions met as equals,” when the story of the Jesuits’ work in China a thousand years later reflects exactly this spirit.

So, too, I was disappointed by a chapter on the nineteenth-century Taiping rebellion, which gets a perfunctory treatment based on a limited use of secondary sources. This and a general unfamiliarity with Chinese history leads to several mistakes, such as the claim that “the Taiping rebellion was one of the earliest religion-inspired revolts in Asia,” when in fact Chinese history is full of religious uprisings.

Far more interesting would have been a chapter on early-twentieth-century Christianity in China. This was the era of Watchman Nee and Wang Mingdao, preachers who explicitly rejected missionaries’ approach to the faith and laid the groundwork for Christianity’s explosive growth today. Like the thinkers that Sugirtharajah cites from the subcontinent, these Chinese Christians downplayed the denominational differences imported by missionaries and took aspects of the Christian tradition that made the most sense to local worshipers. These two preachers spread Christianity to China’s grassroots so that after the Communist takeover in 1949 and the expulsion of foreign missionaries, the religion had a firm local base and was able to flourish. This would have made a good accompaniment to the South Korean chapter and fit in well with Sugirtharajah’s interest in the decolonization of Christianity.

The problem, of course, in trying to cover such a vast and varied continent is that it is impossible for one scholar to master all of its very different languages, so perhaps these are unavoidable weaknesses. Jesus in Asia remains a stimulating and provocative book that shows how Asians—like people around the world—have been trying for centuries to make the man from Galilee one of their own.

This Issue

October 24, 2019

In Defense of Fiction

Snowden in the Labyrinth

The Real Texas

-

1

The documents were first published by UCA News, a Hong Kong–based Catholic news agency. See “Sinicization of China Church: The Plan in Full,” UCA News, July 31, 2018; and “Protestant Five-Year Plan for Chinese Christianity,” UCA News, April 22, 2018. ↩

-

2

See, for example, the churches mentioned in my “The Brave Catholics of China,” The New York Review, March 6, 2014. ↩