On September 23, less than two weeks before he tested positive for Covid, Donald Trump made explicit what has long been implicit: he will not accept defeat in the presidential election. Asked whether he would “commit here today for a peaceful transferal of power after the November election,” Trump replied, “Get rid of the [mail-in] ballots and you’ll have a very peaceful—there won’t be a transfer, frankly. There will be a continuation.” Earlier that day Trump explained why he wants to appoint a successor to Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court before the election: “This scam that the Democrats are pulling—it’s a scam—the scam will be before the United States Supreme Court.” The plan could hardly have been laid out more clearly. If he loses, he will rely on a Supreme Court, three of whose members he will (he hopes) have appointed, to overturn the result.

In reporting on Trump’s remarks, The New York Times claimed they were “a jarring contrast” to a statement made the previous day by his attorney general, William Barr: “What this country has going for it more than anything else is the peaceful transfer of power, and that is accomplished through elections that people have confidence in.” This was presumably meant to offer some comfort to Times readers, to imply that Barr would not tolerate Trump’s threat to suspend American democracy. But the comfort is false. In reality, the contrast between Trump’s statement and Barr’s is one of tone, not of substance. Barr was answering a question about the election at a press conference in Milwaukee. His reply began, “Obviously I’ve been outspoken and concerned about a last-minute shift to universal mail-in ballots.” In his quieter, more restrained way, Barr was actually supporting Trump’s case—the peaceful transfer of power depends on the validity of the election, but such legitimacy is undermined if there is a large number of mail-in ballots.

Barr has been echoing Trump’s baseless accusations that voting by mail is inherently fraudulent for many months. In an interview with Steve Inskeep on NPR on June 25, Barr raised the possibility of widespread counterfeiting of ballots. Inskeep asked, “Did you have evidence to raise that specific concern?” Barr replied, “No, it’s obvious.” There is only one reason to point to threats for which there is no evidence—to lay the ground for a challenge to the election’s results. In this light Barr’s statement in Milwaukee, far from contradicting Trump’s strategy, could in fact be imagined as the opening premise of a brief from the attorney general to the Supreme Court arguing why huge numbers of votes should be discounted.

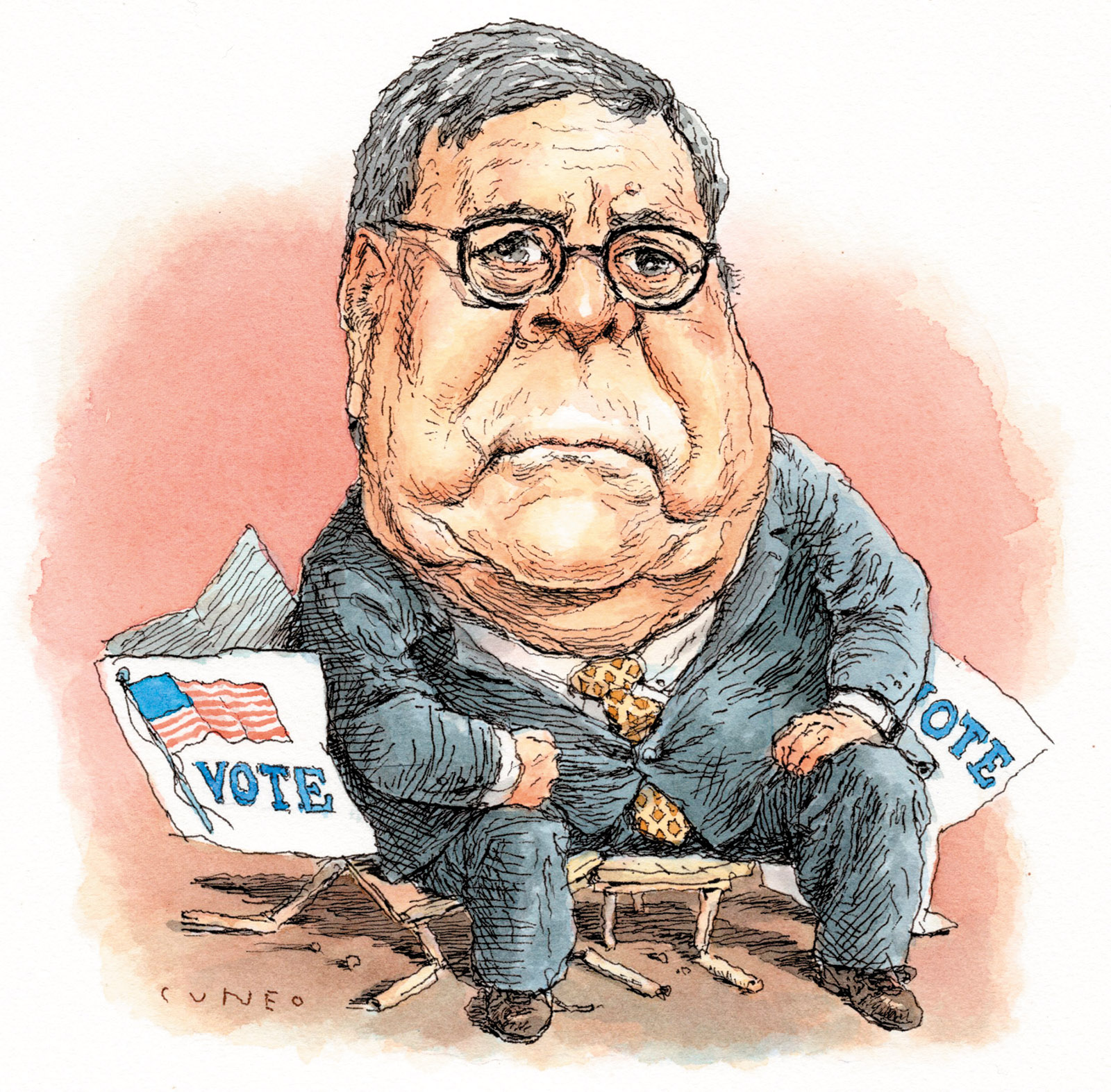

Barr is the single most important figure on Trump’s transition team, but the transition in question is not the democratic transfer of power. It is the transition from republican democracy to authoritarianism. Because of his suave, courteous, even jovial demeanor and intellectual acumen, and his long record as a member of the pre-Trump Republican establishment, it seems superficially plausible to look to Barr as the one who might ultimately seek to restrain Trump and protect the basic institutional and constitutional order. All evidence—including ProPublica’s report on October 7 that the Department of Justice has now weakened its long-standing prohibition against interfering in elections by allowing federal investigators “to take public investigative steps before the polls close, even if those actions risk affecting the outcome of the election”—points in the opposite direction.

The desire to believe in Barr as a potential savior of democracy goes deep. Andrew Weissmann, one of Robert Mueller’s main aides in the special counsel’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, admits, in his new book, Where Law Ends, to sharing this faith:

When I had learned…that Barr had been nominated to replace the much-beleaguered Jeff Sessions as attorney general, the news had brought a sense of relief. All my colleagues in the Special Counsel’s Office believed, as I did, that Barr would likely be an institutionalist…. Barr, I thought, would be like Sessions, who understood the attorney general’s unique place in the firmament of cabinet members: a political appointee on whom it was incumbent to keep his arm of the government independent of politics….

We were counting on Barr, with his prior experience and intellectual heft, to hold that line and maintain the separation of power that is so vital to a democracy.

Weissmann believed that Barr would use the independence of his office “to prevent us turning into a banana republic.” But no one who has thought about Barr’s ideological formation, and in particular his views on the nature of authority, should be so naive.

Accounts of Barr’s career tend, for obvious reasons, to focus on his legal and constitutional opinions. But those opinions are not abstract. They are the surface expressions of a mentality formed in the years of Richard Nixon’s presidency, not just by the turbulent politics of that period but by events much closer to home. In 1974 there were two resonant resignations. One was Nixon’s from the presidency. The other was the unexpected departure of Donald Barr, William’s father and role model, from the headmastership of Dalton, an elite private school on New York City’s Upper East Side. Nixon had fought to assert his complete independence from congressional oversight. Donald Barr resigned from Dalton because he felt his authority was being undermined by its board of trustees. As The New York Times reported at the time, the conflict seemed “to center on the question of where the board’s authority should yield to the headmaster’s judgment.”

Advertisement

It may be a coincidence that Donald Barr’s son became the doughtiest upholder of the principle that congressional authority should yield to the president’s judgment—but if so, it is one even a bad novelist would balk at. When William Barr was beginning his legal career, he chose to clerk for Malcolm R. Wilkey, who, on the federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, had strongly dissented from the majority ruling that Nixon should turn over his secret White House tape recordings because, he argued, a president has an “absolute” privilege to refuse demands from the other two branches of government.

It is striking too that, although these were not the issues that led to Donald Barr’s resignation, he had previously fought off a revolt from Dalton parents who accused him, the Times reported, “of turning a ‘humanistic, progressive’ school into one in which ‘discipline and authoritarian rule’ were the hallmarks.” William Barr is very much part of that nexus of American conservatives who date what he calls “the steady erosion of our traditional Judeo-Christian moral system” to the loss of discipline in the 1960s under the pressure of all the challenges to authority that culminated so dramatically (and, for them, so traumatically) in Nixon’s departure. What his father had done to Dalton—rescuing it from the decadence of progressivism and restoring authoritarian rule—is what Barr has always wanted to do to the United States.

Barr’s path into the apparatus of the state is one on which he followed his father’s footsteps. Donald had worked at the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency. While William was still a student at Columbia, where his father had also enjoyed a distinguished career as a teacher and administrator, he worked as a summer intern at the CIA and in 1973, took up his first full-time job there as an analyst.

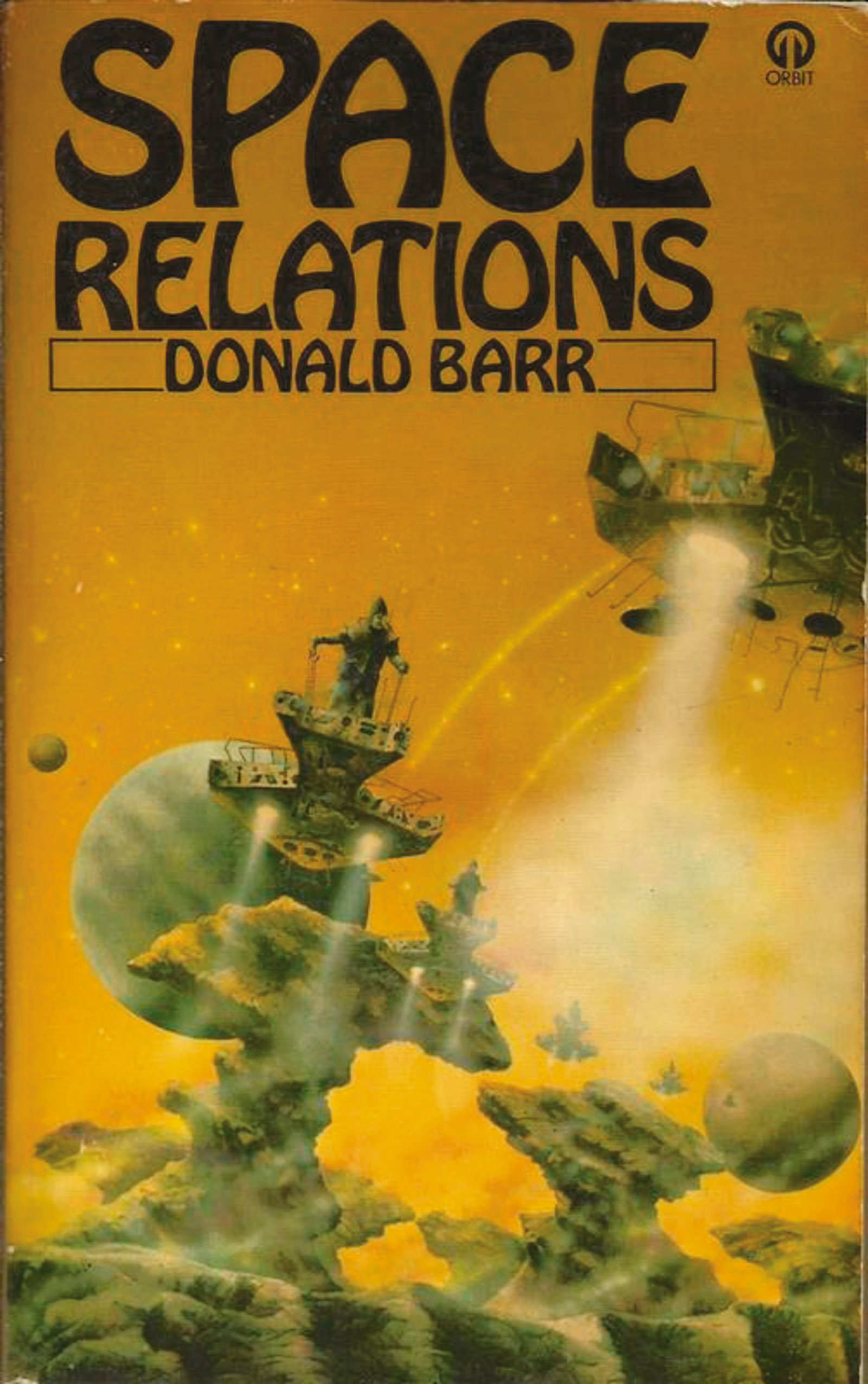

That same year Donald Barr published an atrocious science fiction novel called Space Relations and dedicated it to his wife as a token of “thirty years’ love.” It is a probe launched from conservative, white, male America into the strange inner worlds of its own psyche in the Nixon years. As literature, it is excruciating. But it deals in a usefully unguarded way with themes that bear heavily on William Barr’s present position as Trump’s most formidable enabler: the legacy of slavery, Catholic sexual dogma, the proper response to revolt from below.

The protagonist of Space Relations, the “galactic diplomat” John Craig, is American and white (we learn of his “pallid skin” in the first paragraph). He is, as the book opens, being subjected to “anal and urethral” examinations as part of his preparation for a journey to the planet Kossar. This is, in fact, a return voyage: Craig, we soon learn, had previously been kidnapped by space pirates and sold to a powerful aristocrat on Kossar, a society of slaves and slaveowners. Most of the novel’s action retails his life and adventures during those two years as a slave. Thus, Space Relations is really a thinly disguised plantation novel in which Kossar serves as the Old South. Readers are being pointed in the direction of some allegory of American history.

But the parable is quite demented. First, although the slaves have to call their masters “massa,” and although the book’s title is an obvious pun on “race relations,” the subject of race creeps very slowly into the novel. It literally comes, halfway through the story, as a revelation: “Craig noticed that a surprisingly large number of young slaves were dark-skinned and thought he would ask…about it some day.”

Second, Craig is not just a slave—he is a sex slave. And he greatly enjoys it. His owner is Lady Morgan Sidney,* “heiress of the great fens of Treghast” and possessor too of “high breasts and long thighs.” Craig (or Barr) becomes particularly obsessed with “Her Ladyship’s winsome fundament” and even writes a sonnet (the book is peppered with Barr’s attempts at verse) in praise of her “suave posteriors.” The slave takes a frankly erotic joy in becoming, in thrall to Her Ladyship, a “male concubine, village bull, masochist.” The joyous ending to Space Relations is that Craig, returned to Kossar in his pomp as an emissary from Earth, gets to marry Lady Morgan and live happily ever after. Being a sex slave is obviously the best thing that ever happened to him.

Advertisement

Such, perhaps, are the dreams of the everyday authoritarian headmaster. But the allegory becomes more politically explicit—and more resonant for today—when a slave revolt breaks out on Kossar during Craig’s return visit. His mission is to admit Kossar into the Man-Inhabited Planets Treaty Organization, but one of its rules is that no slaveowning society can join. The slaves, getting wind of this demand that they be emancipated, stage their own anticipatory revolt.

This uprising is pure horror. The slaves are interested primarily in grisly murders and in planning the various ways in which Lady Morgan will be raped. Craig declares that “we can’t let the slaves massacre the free-men, or we’ll have chaos.” He calls in his intergalactic strike force—made up, we are told, of Ukrainians (presumably to signal their whiteness)—to put down the revolt. Slavery is abolished—but by Craig and the interplanetary federation, with the reluctant consent of the slaveowners, and the grand bargain is sealed by Craig’s marriage to Lady Morgan. It seems crucial, in the culmination of the novel, that emancipation is granted from above by the federal authorities, not won from below by the oppressed.

For all its weirdness, this is oddly familiar. The author’s son is now the chief embodiment of the law in the United States. A revolt from below against the continuing legacy of slavery is in progress. And William Barr wishes to ensure that, even if the protesters have justice on their side, it is for the federal government to decide in its own way and in its own time how to deal with their problems. Craig’s fear—“we’ll have chaos”—is the rallying cry and the primary electoral message of Barr’s boss, Donald Trump. Barr has thrown the full weight of the justice system behind a focus not on the peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters, but on those he calls “the people out committing the destruction and the chaos.” Barr has sent armed federal strike forces into US cities. There is more than a touch of Space Relations in Barr and Trump’s approach to race relations in 2020.

Another aspect of his father’s wacky novel is highly relevant to William Barr’s view of the world. Along with the masochistic sexual fantasies and the weird allegory of slavery, Space Relations has a third major theme: Catholic teaching on sexuality and reproduction. Donald Barr was not raised a Catholic, but joined the church under the influence of his Irish-Catholic wife, Mary Margaret Ahern, a college professor, and became a fervent upholder of its most hard-line doctrines. The least lurid reflection of this in the novel is at the end, when Craig dramatically strikes out from his marriage contract with Lady Morgan a clause permitting a divorce—a practice outlawed by the Catholic Church. The attacks on homosexuality, transsexuals, abortion, and Planned Parenthood are rather less gallant.

Characters are referred to as “the old queen” or “the old queer.” Early in the novel, Craig lures a male slaver into beginning to have sex with him, then stabs him and leaves him to bleed out slowly. He celebrates the moment with a poem. Later, Craig is revolted to discover that one of the slave-masters has created, for his pleasure, a minion named Sugar-lips who has both male and female sexual characteristics and a “strong libido.” Lady Morgan, meanwhile, has tried to force Craig to become a stud at her slave-breeding facility, which is called (naturally) the Planned Parenthood Center. There, the slave girl he is to “do” produces a short lecture on abortion:

Oh, many times when the women have been done, they try to kill the baby, you know? Inside. Because they say they don’t want to bring a baby into the world if it’s going to be a slave. But I say that’s silly…. A slave could escape—or something…. But if he wasn’t even born, he couldn’t ever escape. That’s even less of a chance, if you see what I mean. I always need to tell them, I’m a slave and I’d rather be that than not even be there at all.

Abortion, in other words, is a worse crime than slavery. And for William Barr, Roe v. Wade, not slavery, is America’s original sin, the moment at which the fall from “traditional moral order” begins. It is what he called, in a highly revealing speech in October 2019 at the Catholic university Notre Dame, where Trump’s Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett both studied and taught law, “the watershed decision.”

The literary sins of the father—especially ones as grave as Space Relations—should not be visited on the son. There is, however, a very strong connection between Donald Barr’s hard-line Catholicism and William Barr’s present position as the main (perhaps the sole) intellectual buttress of Trump’s presidency. That connection lies in the idea of authority. Authoritarian rule is a defining feature of hierarchical institutional Catholicism. The magisterium of the church flows from the pope, who, on matters of faith and morals, may create doctrines that are infallible and therefore unquestionable. These include the bans on contraception, divorce, abortion, homosexual sex, and same-sex marriage. As a devout Catholic with links to the powerful Opus Dei movement, which galvanized the successful reaction against the liberalizing currents within the church, Barr holds to these principles as both articles of religious faith and bulwarks of the social order. In this, he is a central figure in the ever-growing influence of right-wing Catholicism under Trump, demonstrated yet again in his nomination of Barrett to the Supreme Court.

From the beginning of his political career in the administration of George H.W. Bush, in which he served as assistant attorney general, deputy attorney general, and eventually attorney general, Barr’s biggest concern has been to assert the rights of a quasi-papal presidency. In a for-the-record interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, Barr recalled that, having worked on Bush’s campaign, he was brought into the administration to lead the Office of Legal Counsel because the head of Bush’s transition team, Boyden Gray, “was intent on getting someone in that position who believed in executive authority.”

“Believed in” is important here. Barr’s understanding of executive authority is no more a matter of constitutional reasoning than a zealous Catholic’s acceptance of papal infallibility is a result of cool biblical analysis. It is a matter of faith. Barr explained in that UVA interview why he believed that Bush had the power to go to war against Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait without seeking the approval of Congress:

First, I believed that the President did not require any authorization from Congress, and I believed that the President had constitutional authority to launch an attack against the Iraqis. But I also knew that it didn’t much matter what I thought, because that’s what he was going to do. He believed he had the authority to do it, and that’s ultimately more important than what I believe.

Barr’s point here is that, even if he himself had believed that Bush could not declare war on his own, that would not matter. What matters is what the president believes. If he has faith in his own authority, the job of his lawyers is not to question that faith but to defend it.

This is what makes Barr the perfect enabler of authoritarianism. The law, in his eyes, does not constrain the president’s will but rather serves it. This is precisely, according to Barr’s own description, what happened in the case of the first Iraq war. At a high-level meeting, Bush asked him directly whether he as president had unilateral authority: “I’m sort of flattered that he asked me a cold question without having discussed it with me first, because it meant he knew what answer I was going to give him.” Bush knew the answer because, in Barr’s world, when the president asks if he can do what he wants to do, the answer is always yes.

What must be understood about Barr is that he is not a lawyer in the political arena. He is a political ideologue and operative who happens to function through the law. In that same meeting with Bush, Barr went on to advise him that, even though he had no legal requirement for congressional approval, he should, for purely tactical reasons, seek it anyway. Dick Cheney, then defense secretary, intervened to admonish Barr for straying into political advice. Barr, on his own account, replied, “No, I’m giving him both political and legal advice. They’re really sort of together when you get to this level.” In truth, for Barr, they are much more than “sort of together.” They are inextricably entwined. His function in public life, as he has always understood it, is to provide legal justification for the untrammeled exercise of power by Republican presidents. And for all his air of gravity, Barr is utterly shameless in his pursuit of this calling. He is willing to lie to the American people and to flout the very principles he claims to uphold.

That, after all, is precisely why Trump appointed him as attorney general in February 2019. Trump, in his rage against his original appointee, Jeff Sessions, insisted that the primary job of the attorney general is to protect the president from scrutiny by law enforcement agencies and by Congress. This, in effect, is what Barr promised to do. In the long unsolicited memo that served as his job application, Barr wrote:

Under the Constitution, the President’s authority over law enforcement matters is necessarily all-encompassing, and Congress may not exscind certain matters from the scope of his responsibilities…. The President’s law enforcement powers extend to all matters, including those in which he had a personal stake.

Moreover, the president’s motives in exercising these all-encompassing powers cannot be questioned, even if they are ostensibly corrupt and self-serving, since to do so would

cast a pall over a wide range of Executive decision-making, chill the exercise of discretion, and expose to intrusive and free-ranging examination…the President’s (and his subordinate’s) subjective state of mind in exercising that discretion.

Barr’s pitch to Trump was honest enough—if you want someone to apply a veneer of intellectual respectability to the unaccountable exercise of your own desires and instincts, I’m your man. There might be something to admire in the consistency of Barr’s extremist position over five decades. But even this is to give him too much credit. The principle involved here is not a devotion to a particular interpretation of the constitution. It is his far deeper devotion to the unaccountability of specifically Republican occupants of the White House.

Barr is consistent only in his hypocrisy. As David Rohde has pointed out in The New Yorker, Barr described as “preposterous” the argument made by Bill Clinton’s legal team during the Whitewater investigation that he was not obliged to comply with a subpoena from a Senate committee demanding that he hand over documents. Yet Barr, as Trump’s attorney general, refused to appear before the House Judiciary Committee and repeatedly refused to hand over documents requested under subpoena by the House Oversight and Reform Committee.

In a 1998 interview Barr said that he was “disturbed” that then attorney general Janet Reno had not defended the Whitewater independent counsel Ken Starr from “hatchet jobs” and “ad hominem attacks.” Trump’s constant attacks on Mueller evoked no such disturbance. In a recent speech, Barr piously proclaimed that the “criminalization of politics is not healthy…. The political winners ritually prosecuting the political losers is not the stuff of a mature democracy.” Yet he seemed completely untroubled by Trump leading chants of “Lock her up!” aimed at Hillary Clinton. Barr says that “the essence of the rule of law is that whatever rule you apply in one case must be the same rule you would apply to similar cases.” By that standard, Barr’s commitment to the rule of law is self-evidently negligible.

Can we rely, then, on the Catholic conscience that he claims, quoting Father John Courtney Murray, is “governed by the recognized imperatives of the universal moral order”? That universal moral order does not, apparently, prohibit the telling of lies to hundreds of millions of citizens. In a March 2020 opinion, senior US District Court Judge Reggie B. Walton, an appointee of George W. Bush, wrote that Barr “distorted the findings in the Mueller Report” when he issued a grossly misleading “summary” before the report itself was published, in order to “create a one-sided narrative about the Mueller Report—a narrative that is clearly in some respects substantively at odds with the redacted version of the Mueller Report.” In Where Law Ends Weissmann records his shock that “Barr had spun our findings for political gain, at best, and lied for the president, at worst.” He had of course done both.

How does Barr square such conduct with his identification of “moral relativism” as the great enemy of society, the theme of his speech at Notre Dame? The answer illuminates the deep religious structure of Barr’s ideology. The term is a touchstone for the conservative Catholic reaction against the liberalizing tendencies of Vatican II in the 1960s. It has a rhetorical advantage—by being against “moral relativism,” one does not have to say that one is in favor of moral absolutism. But its primary purpose is to delegitimize the republican view of democracy as an arena that is neutral with regard to religious identity and belief. It divides citizens into the proper ones who recognize the authority of divinely inspired absolutes (prohibitions on abortion or same-sex marriage, for example) and the improper ones who do not.

Barr’s core belief, shared by Vice President Mike Pence and by the wider evangelical brand of religious authoritarianism, is that the entire American polity is possible only if its citizens are not just religious believers but believers in an absolutist “transcendent moral order which flows from God’s eternal law.” Barr claims that the framers of the Constitution believed that

free government was only suitable and sustainable for a religious people—a people who recognized that there was a transcendent moral order antecedent to both the state and man-made law and who had the discipline to control themselves according to those enduring principles.

This “religious people” is, in Barr’s explication, variously “Christian” or “Judeo-Christian.” It does not include members of other faiths, let alone atheists or agnostics. Just as importantly, it does not include those guilty of what Barr openly calls in that speech “apostasy.” Apostates include, for example, the 77 percent of Democratic and Democratic-leaning Catholic adults who think abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and who have therefore committed the mortal sin of moral relativism. Among them is the man who might become only the second Catholic president in US history, Joe Biden, and the voters who might make him so.

All of these people are not, in Barr’s view, merely misguided. Their indiscipline condemns them to an exterior darkness, beyond the realm of the authentic citizenship of the holy elect. Their very existence undermines the true nature of the United States. Since “free government” is not “suitable [or] sustainable” for those who do not accept the divine law as interpreted by conservative Christians like Barr, it can exist only in their absence. The logic is not just that their votes are outside the rightful order of the American state but that they are the malign means to undermine it. To suppress those votes would be to uphold the authority not just of Donald Trump, but of God.

—October 7, 2020

-

*

This is presumably an homage to the early nineteenth-century Irish novelist Sydney, Lady Morgan. ↩